- 516 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

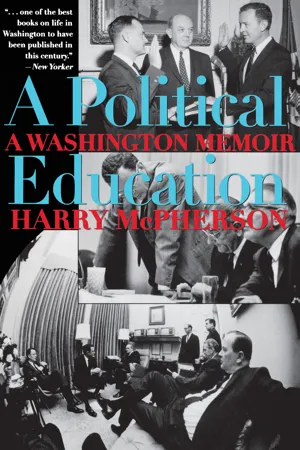

This classic political memoir offers an insider's view of Washington in the '50s and '60s—with a preface by the author reflecting on the Clinton era.

A Texas native, Harry McPherson went to Washington in 1956 as an assistant to Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson. He served in key posts under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, including as Johnson's special counsel and speechwriter.

In Political Education, McPherson offers a vividly evocative portrait of Johnson's tumultuous presidency and of the conflicts and factions of the president's staff. Long regarded as a political classic, it is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand national politics of the period.

In 1995, McPherson added a preface discussing how Washington had changed since the Johnson era. In it he suggests what lessons Bill Clinton could have learn from Johnson's time in the Oval Office.

A Texas native, Harry McPherson went to Washington in 1956 as an assistant to Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson. He served in key posts under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, including as Johnson's special counsel and speechwriter.

In Political Education, McPherson offers a vividly evocative portrait of Johnson's tumultuous presidency and of the conflicts and factions of the president's staff. Long regarded as a political classic, it is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand national politics of the period.

In 1995, McPherson added a preface discussing how Washington had changed since the Johnson era. In it he suggests what lessons Bill Clinton could have learn from Johnson's time in the Oval Office.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Political Education by Harry McPherson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Counsel in Congress

I HAD last seen Washington in August 1950. One suffocating evening in Manhattan, I decided to visit a girl in Georgia, and persuaded a New York Irish couple—Tom Dardis was a fellow graduate student at Columbia, a literary man—to go with me. Next morning we left the train in Washington and decided to hitchhike south. Tom insisted that we visit the Library of Congress first. While he and his wife went inside, I stood on the steps, taking the hot waves of Washington summer, looking across to the Capitol.

Congress was debating the Korean War. The Secretary of State was catching it from the Republicans, allegedly for having left Korea out of his ambit of American concern and thus inviting its invasion. Off-year elections were not far away. The nation was at war, and partisan politics, over there across the park, were intense.

A streetcar banged heavily by. A dozen pigeons slowly avoided a company of tourists. An elderly guard came out for a smoke and asked if it were hot enough for me; he didn’t know whether the Democrats were likely to retain control over Congress after November, but he certainly hoped a certain senator made it back, because he was sponsoring a retire-after-thirty-years bill for federal employees. The senator was a profound conservative. That the old library guard, a uniformed member of the proletariat, should be concerned about the return of a conservative Republican senator, was shocking.

I thought that I should have to revise my estimate of political allegiance. I had left out self-interest among blue-collar groups, the kind that I ascribed automatically to banks and the AMA. Apparently not all the working poor read editorials and took up their assigned positions on the barricades.

I was struck, too, by the tranquillity of the scene. The park, with its variety of graceful trees; a few cars, shimmering in the morning sun; beyond, the Capitol. This was the theater, and inside that building was the stage, where the country’s passionate preoccupations were acted out: the loss of China, the fight for Korea, the presence or the empty accusation of Communists in government, states’ rights, and cruelty to Negroes. Sulphurous issues, the “fury and the mire of human veins.”

But if there were conflict and meaning on the stage within, there was, out here, all the complacency of a Southern courthouse square. It was inconceivable that a mob should storm this place. Representative government, I thought, required only that men should sweat and shout and beg and cheat until they were elected to office, whereupon they might quit the small towns, travel to Washington—and enter a mausoleum surrounded by a scene from Fragonard.

The air was colder the next time, and I was something other than an observer from across the park. I had been hired as assistant counsel of the Senate Democratic Policy Committee, and one morning in early February 1956, I made my way among tourists and messengers toward the committee’s room on the third floor of the Capitol.

It was crowded. Six or seven people were at desks in a highceilinged room whose deeply set windows looked out on the Mall and the Monument, the great mass of official architecture known as the Federal Triangle, and Pennsylvania Avenue down to the Treasury.

It was a breathtaking idea: to work at the very point to which this scene appeared to be tending, and from which it radiated. The view itself was satisfying, in a remote, intellectual way. It was what one expected. One sees Parliament across the Thames, looking just as it does in a thousand drawings and descriptions; the Arc de Triomphe; the Pope’s miter. There is nothing human, nothing surprising or moving about such things at first. It takes time before one feels the striving, the inspired foolishness that went into making them. Months later, in a happy, drunken twilight, I looked out and finally felt that scene.

Now to find out what I was hired to do. The counsel of the committee, and my boss, was Gerald W. Siegel, an exceedingly kind and intelligent man who had come to the committee from the staff of the Securities and Exchange Commission. He had worked for Donald Cook, when Cook chaired the SEC by day and briefed Lyndon Johnson in the Senate Preparedness Subcommittee by night. Thereafter Johnson had persuaded Gerry Siegel to become his lawyer.

Gerry had too much on his hands in 1955. Johnson’s heart attack had not relieved the pressure on key Senate staff members. If anything, serving Earle Clements, the acting leader, and other members of the Democratic leadership—as well as the convalescent Johnson—had been even more demanding. Gerry asked for help. Johnson agreed, provided he found someone from Texas—I suppose to offset Gerry’s Iowa and Yale background, perhaps ultimately to help with Texas problems. So I had been hired.

To do what? To counsel the “Senate Democratic Policy Committee.” That had an imposing sound. But what did it mean, why was the committee so rarely in the news?

It had been proposed in 1946, in the LaFollette-Monroney hearings on the reorganization of Congress. It was a political scientists’ idea, a structural reform of Congress. Each party was to have a policy committee which would define party doctrine, and take party positions on issues that arose between Presidential elections. It was to be a kind of permanent floating party platform. By this the country would know what Democrats and Republicans thought, who in each party had been faithful to those thoughts, and who had strayed. Clearly the intention was that American politics would more closely approach the ideological mode of Europe. Particularly in mid-term elections, the voters would have a definite choice, not merely between personalities, but between ideas of government.

Those who spoke for this reform in 1946 included not only political scientists, but representatives such as Estes Kefauver and Sherman Adams. Without a word of debate, the Senate adopted it. This was not because it was indisputable, but because senators were more concerned with other matters in the reorganization bill—particularly the size and compensation of Senate staffs. First things first. Few issues command the alert attention of senators as do the salaries and composition of their staffs and of Senate committees.

In the House it was another matter. There was no sign of conflict over the policy committees, but the bill emerged without a mention of them. Pretty clearly the Speaker and Chairman Smith of the Rules Committee had decided that no other entities but themselves should determine policy in the House.

Yet they must have agreed that if senators felt strongly about policy committees, they should have them. Almost at once Congress passed a supplemental appropriations bill in which funds were provided for the staffs of two policy committees. There was no detailed description of their roles. That would be worked out as time went along.

It seemed natural that the Senate Democratic leader would head his policy committee, and so Scott Lucas of Illinois became chairman. Senator Lucas—whom I knew only slightly, long after he had left the Senate—was a kind of Burning Tree Club liberal, generally faithful to President Truman’s program, but not inclined to impress his or the President’s views on the heterogeneous Democratic membership of the Senate. The original purpose of the policy committees may have been to set policy, to draw lines; but if this was ever possible among Senate Democrats, it was not attempted. Lucas’s successor, Ernest McFarland of Arizona, was even less determined to shape a unified party position, and even less capable of it.

The Senate Republicans at that time were far more cohesive in their views. All but a few were generally set against government spending and federal regulation of business. It was therefore relatively easy to establish a Republican position against legislation which would have either effect. The Republican Policy Committee met frequently for lunch and discussion, after which their chairman would emerge to announce Republican opposition to the latest Democratic spending program.

By 1956, the pattern of the Democratic Policy Committee had been fixed. The committee met biweekly, more or less. The counsel explained the bills on the Senate Calendar—the bills that had been reported by the standing committees, and not yet passed. Members of the committee authorized the chairman to call up certain bills for action by the Senate, and asked him to delay others. They debated the merits and politics of each major bill on the Calendar, and of many that were still pending in the standing committees. In effect, they constituted a Senate version of the House Rules Committee. They were a screen of generalists, controlling the flow from the specialist committees.

The thrust of the Reorganization Act had come to this in the Senate Democratic Policy Committee, partly because it was impossible to resolve differences of opinion between men like Hubert Humphrey and Harry Byrd, or Paul Douglas and Richard Russell; partly because Democrats had been in operational control of the Senate during most of the time since the act was passed, and thus it was easy to ignore the ideological problem in favor of the functional job of setting the Senate’s program. Republicans, basically more unified in opinion, were also generally in opposition. Having no leadership responsibilities, they had time to be philosophical.

The Republican committee always made news. Opposition to anything in Washington is guaranteed a few lines in the newspaper. Usually all that emerged from the Democratic Policy Committee was a list of bills to be motioned up. Depending on Johnson’s mood, that might cover only three or four major bills, or—if the Senate had been accused of dawdling by the press—it might run the gamut from major programs to private immigration bills, their titles read off in the Senate chamber with equal emphasis as if to say, “There, by God, don’t say we’re not attending to business!”

More than two years passed before I was asked to sit with the committee and brief them on pending legislation. My job at first was to serve as counsel to something called the “Calendar Committee.” This was composed of two or three junior senators, who dutifully gathered in the Democratic cloakroom on mornings before the Senate was to have a “Calendar Call.”

I often wondered what schoolchildren in the galleries thought of constitutional government when a Calendar Call was in progress. The atmosphere was one of controlled panic, like a tobacco auction. A thin, dark-eyed clerk read off the number and title of every bill—there were sometimes hundreds of them—with a machine-gun rapidity that was interrupted occasionally by a senatorial shout of “Over!” If there was no interruption, the bill passed, by unanimous consent. “Over!” meant that the bill remained on the Calendar.*

In this way the bulk of the Senate’s work was done, at least in number of bills passed. Immigration bills, private claim bills, minor statutory amendments, and sometimes even significant legislation which, for one reason or another, senators did not choose to debate, passed the Senate on Calendar Call and made their way to the House or the President.

After a call was announced, usually several days in advance, I read the bills and reports, and prepared myself to brief my small committee. Senators and their staffs phoned to register objections to certain bills—Senator Morse objected to the grant of certain federal land, because the grantee was not required to pay for it; Senator Gore disliked immigration bills for mentally defective girls, mindful, I suppose, of genetics in the Tennessee hills; Senator Magnuson did not object to a lumber marketing bill if the Calendar Committee would offer an amendment to it and secure its adoption. My Calendar was covered with notes as I left, heavy books of bills under both arms, for the cloakroom.

There I would explain the bills and relate the objections I had received. Sometimes an objection raised a problem for the committee members, because they had assured the author of the bill—frequently a powerful congressman—that they would get it through. Then began a great rushing around, seeking out the objector, urging him to withdraw his “hold” on the bill, phoning to warn the congressman, and perhaps writing a last-minute amendment that eased it by.

Ordinarily the members of the Calendar Committee were in agreement on whether or not a bill should pass on the call. Ideological differences did not interfere. One of the best committees was composed of Herman Talmadge and Joseph Clark, whose views of the world could scarcely have been more opposed. In two years of service on the committee, they disagreed no more than twice. Watching them, I learned my first lesson in the nature of the Senate: that the famous “club” atmosphere is based on the members’ mutual acceptance of responsibility and concentration on tasks at hand. This governed both a fledgling member of the Establishment, Talmadge, and one who would always be outside it, Joe Clark. For those obsessed with the morality of political opinion, an easy working relationship between a Southern conservative and Northern liberal, even on mundane affairs such as the Calendar Committee, might have suggested a sellout by one or the other. For the men involved, however—though they thrust hard at one another in debate over serious matters—understanding and accommodation in the ordinary course of the Senate day was essential to sanity. Probably the high proportion of lawyers in the Senate, men accustomed to sharing a meal after thrashing one another in court, had something to do with that.

Once on the Senate floor, and the call begun, the tension was terrific. For two or three hours I sat with my committee, reminding them to offer an amendment, whispering information when they were questioned about a bill, all the while praying that I was right. We were onstage, under the professional scrutiny of other senators and staff, with a half-dozen gargoyles of the press leaning over the rail of the gallery directly above us. A less informed but probably perceptive audience sat in the other galleries, waiting, I thought, like the mob in Barrault’s Children of Paradise, to break into cheers or catcalls at any moment. From time to time I would rush forward to hand the clerk an amendment received from an absent senator, or hoarsely instruct a page to tell another senator in his office that he must come at once if he wanted to be heard on a bill.

At last it would end. Piles of discarded notes and reports lay about us. I would become aware that my shirt was soaking, that I was weary and terribly hungry. But before I went for lunch, I would return to the Policy Committee room and tell the staff, with pride and amazement, that we “passed 175 bills today!” Helping to do that was casting a shadow—very faint, very thin, but a shadow.

I spent a lot of time, in those first two years, walking the halls of the Capitol and of the office buildings, talking with committee professionals and members of the senators’ staffs, discussing rules with the parliamentarian. Studying the Senate rules and precedents seemed about as dry as writing a will, but it soon became clear that command of the rules was one of the most powerful weapons in the conservative arsenal. Senator Russell knew them intimately. Senator Lehman did not. And there was nothing to be done with a farsighted liberal amendment, tabled, consigned to committee, ruled not germane, or otherwise held not to be in order, but offer it to the press as something that might have been. Thus I tried to learn the rules.

An ancient, good man tried to teach them to me. Charlie Watkins had been around the Senate for fifty years or more, and his patience was considerable, as it had to be. Often senators who felt themselves abused by a ruling from the chair descended into the well of the Senate—the semicircular depression where I sat, absorbed by the debate or distracted by a pretty girl in the gallery—descended and set upon Charlie with a vehemence that stopped just short of abuse. He listened patiently, and in his old, Pepperidge Farm voice, explained why he had advised the presiding officer to rule as he did. An ultimate respect for Charlie and his knowledge of the rules, and a fervent desire to be on his side next time, sent the senators grumbling back to their seats.

Charlie Watkins and Ed Hickey, the Journal clerk who sat beside him, epitomized the old values of public service by government functionaries. The world needs men of such impartiality and complete dedication to task and institution. It is hell to encounter their opposites—those who must be bought, and if bought, will not stay bought; those so governed by whim or peevishness or simple lust for advancement that they will bend any rule and ignore any precedent in their service. Public life controlled by such men is chaos itself.

Yet as I looked at Ed Hickey, with his lantern jaw and cavernous mouth sprung open with the work of the Journal, on which he scratched like a character in Dickens; or at Charlie himself, crucial as he was; or at the other clerks who maintained the mechanics of the Senate—with little concern for the issues in debate, so often had they heard them, so much bull, so much posturing—I thought that I would avoid such a life at all cost. As Charlie grew very old, it was once suggested that I succeed him. The idea struck me with horror. I thought it was time to be moving on.

We were, nevertheless, a company. There was an esprit de corps among us, something of the irreverence of valets toward great masters, something of their pride in reflected glory. At moments of high drama, late at night, with the galleries packed, the press seats filled, the hour of a historic vote having come, there was no place else to be. Even the pages—droll boys who looked as if they had just sneaked back from a forbidden smoke in the men’s room—shared our excitement at such times.

After a while I had two jobs in the Senate, one as a mechanic helping to move legislation through, the other as legislative assistant to the leader. In the latter role I came to know many of the other men, most of them young lawyers, economists, or journalists, who served individual senators as bill-drafters and speech-writers. It was heady work for some. If a senator was an activist, if he served on the right committees or simply had the right interests, his legislative assistant moved in a high-pressure world of cabinet officers, academicians, and Washington lobbyists.

Ben Read, with Senator Clark, became an expert on the issues of nuclear war and peace—an understanding he was to carry into the State Department as its executive secretary. Frank McCulloch and Howard Shuman provided Senator Douglas with limitless information on economic and social matters. When Mike Monroney offered an amendment, Tom Finney sat beside him, feeding him facts and arguments. Ted Sorensen and Mike Feldman with John Kennedy; Oliver Dompierre with Knowland and Dirksen; Steve Horn with Kuchel; John Zentay with Symington; Don McBride with Kerr—such men were indispensable, not only to their senators, but to the entire process of legislating. If their senators were occupied with politics or a thousand constituent chores, the legislative assistants understood and remembered the issues at stake in every vote. We argued for hours over army coffee in the Senate restaurant, challenging each other’s judgments, debating—in far simpler terms than those used upstairs on the floor—the merits of pending bills, collecting intelligence on each senator’s intentions and motivations. We assumed that the Senate could not do without us. And when an amendment we had prepared or a speech we had written was offered on the floor, we thought we cast an ineluctable shadow.

The committee staffs were a mixed lot. The size and quality of each had much to do with its chairman. Senator Byrd of Virginia, whose ideas of economy reflected those of an eighteenth-century shopkeeper, allowed the Finance Committee a single professional staff member. Senator Russell had not many more on Armed Services, though they were competent and knowledgeable.

Where Southern conservatives predominated—as on the Judiciary Committee—the Southern chairmen were quite permissive about staff. Each of the senior men on Judiciary chaired a subcommittee, where he could entrench a number of faithful retainers. This system had its drawbacks for Chairman Eastland in the case of Senator Kefauver and his Anti-Trust Subcommittee. Conservatives did not want the subcommittee chairmanship, as it was by nature troublesome and aggressive toward business; and yet the demands of committee loyalty required Eastland to defend—halfheartedly, but symbolically—Kefauver’s expensive staff requests. It was a dilemma with which Eastland never seemed comfortable.

Committee staff members were inclined to remain in the Senate far longer than were individual assistants to the members. The committees themselves were institutions. Senators came and went, but Appropriations remained. Even men who had migrated to committee staffs because their sponsors had no room on their own, or because of a chairman’s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface, 1995

- Prologue

- 1. Counsel in Congress

- 2. Brief Lives

- 3. Right from Wrong

- 4. Cold War Democrats

- 5. Sacred Cows and Racial Justice

- 6. Johnson for President

- 7. Racing in Neutral

- 8. Army and State

- 9. White House

- 10. Cities Aflame

- 11. Democracy Fights a Limited War

- 12. Dénouement

- Epilogue

- Postscript, 1988

- Index

- Footnotes