- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Detail[s] the grassroots interplay among the variety of ideologies, individuals, and organizations that made up the Chicano movement in San Antonio, Texas." –

Journal of American History

In the mid-1960s, San Antonio, Texas, was a segregated city governed by an entrenched Anglo social and business elite. The Mexican American barrios of the west and south sides were characterized by substandard housing and experienced seasonal flooding. Gang warfare broke out regularly. Then the striking farmworkers of South Texas marched through the city and set off a social movement that transformed the barrios and ultimately brought down the old Anglo oligarchy. In Quixote's Soldiers, David Montejano uses a wealth of previously untapped sources, including the congressional papers of Henry B. Gonzalez, to present an intriguing and highly readable account of this turbulent period.

Montejano divides the narrative into three parts. In the first part, he recounts how college student activists and politicized social workers mobilized barrio youth and mounted an aggressive challenge to both Anglo and Mexican American political elites. In the second part, Montejano looks at the dynamic evolution of the Chicano movement and the emergence of clear gender and class distinctions as women and ex-gang youth struggled to gain recognition as serious political actors. In the final part, Montejano analyzes the failures and successes of movement politics. He describes the work of second-generation movement organizations that made possible a new and more representative political order, symbolized by the election of Mayor Henry Cisneros in 1981.

"A most welcome addition to the growing literature on the Chicana/o movement of the 1960s and 1970s." – Pacific Historical Review

In the mid-1960s, San Antonio, Texas, was a segregated city governed by an entrenched Anglo social and business elite. The Mexican American barrios of the west and south sides were characterized by substandard housing and experienced seasonal flooding. Gang warfare broke out regularly. Then the striking farmworkers of South Texas marched through the city and set off a social movement that transformed the barrios and ultimately brought down the old Anglo oligarchy. In Quixote's Soldiers, David Montejano uses a wealth of previously untapped sources, including the congressional papers of Henry B. Gonzalez, to present an intriguing and highly readable account of this turbulent period.

Montejano divides the narrative into three parts. In the first part, he recounts how college student activists and politicized social workers mobilized barrio youth and mounted an aggressive challenge to both Anglo and Mexican American political elites. In the second part, Montejano looks at the dynamic evolution of the Chicano movement and the emergence of clear gender and class distinctions as women and ex-gang youth struggled to gain recognition as serious political actors. In the final part, Montejano analyzes the failures and successes of movement politics. He describes the work of second-generation movement organizations that made possible a new and more representative political order, symbolized by the election of Mayor Henry Cisneros in 1981.

"A most welcome addition to the growing literature on the Chicana/o movement of the 1960s and 1970s." – Pacific Historical Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Quixote's Soldiers by David Montejano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

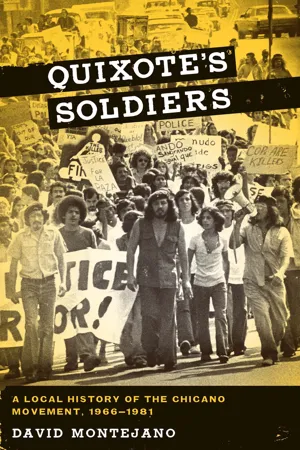

Valley marchers arrive in San Antonio, August 27, 1966. San Antonio Express & News Collection, University of Texas at San Antonio Institute of Texan Cultures, E-0012-187e-4.

THE CONFLICT WITHIN

IN EARLY 1966, the San Antonio newspapers were filled with front-page items that highlighted the protests and troubles taking place across the country. In mid-March (March 16–18), a flare-up involving “600 Negroes” had taken place in Watts, California. The disturbances, which had spread to Pacoima and involved Black and Mexican youths, were considered “minor” compared to the riot of the previous August, when thirty-four people had been killed and $30 million of damage inflicted. The following week, on March 27, thousands marched in anti-Vietnam War protests throughout the country. On April 11, striking grape pickers, led by César Chávez, completed a 300-mile march to Sacramento. And in mid-May, racial tensions in Los Angeles erupted again in “the Negro section,” prompting Floyd McKissick, director of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), to warn of possible race violence in forty cities.1 Against this backdrop, San Antonio appeared to be a bucolic oasis—with the exception of its Mexican barrios.

While the Black civil rights movement and the farmworker strikes were beginning to stir Mexican American communities throughout the Southwest, San Antonio was in the midst of juvenile gang warfare. Drive-by shootings in the Mexican “West Side” had become a regular occurrence and the subject of considerable public discussion. Six months of violence had left one dead and more than a dozen wounded. The death had occurred in front of the Good Samaritan Center after, in the words of a newspaper account, a “poor boy” dance. The settlement houses, established to serve the poor neighborhoods, ironically seemed to serve as sites for conflict; they seemed inadequate for the task of maintaining peace. Sgt. Dave Flores, speaking of the month of May, said, “We have been having a shooting in the area almost nightly for the past month.”2

Later that summer, in August, a ragtag procession of one hundred striking farmworkers and supporters from the lower Rio Grande Valley marched through San Antonio, singing “We Shall Overcome.” They were on their way to Austin to meet with the governor, John Connally. It was the first sign of a brewing political storm for San Antonio and South Texas. When Governor Connally refused to meet with the marchers, the rebuff merely strengthened the resolve of the farmworkers and their youthful supporters. The farmworker cause gathered still more momentum when the Texas Rangers roughed up and arrested some strikers and supporters in a highly publicized confrontation a few months later. Through such high-profile conflict, the farmworker strikes in the lower Rio Grande Valley and in California became the catalyst for the first stirrings of a Chicano movement in San Antonio and throughout Texas.

In the mid-sixties, San Antonio was a paternalistic, segregated society ruled by a handful of old Anglo families. A sizable fraction of the population (four out of ten residents) lived in impoverished Mexican American barrios. The recognized Mexican American leadership was divided over how to respond to these conditions, on whether to stay to its gradualist approach to politics or to adopt a more aggressive stance. Into this discussion ventured some impatient college students who, inspired by César Chávez and the farmworker cause, began to challenge the established leadership. They recruited not just other students, but also the street youths into an emerging movement organization, the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO). One controversial MAYO project was a “freedom school” where college students and barrio youths could discuss and learn about “la causa” (the cause), “carnalismo” (brotherhood and sisterhood), and a “raza unida” (united people).

Through such deliberate efforts, the demand for equality and justice, framed within an ideology of Chicano cultural nationalism, touched all sections of the Mexican American community, including the “gang” youths of the impoverished barrios. School walkouts, protest rallies, and the emergence of a Chicano political party were consciousness-raising events for barrio youths. The formation of the Brown Berets was an organic expression of this political consciousness. As a result, the Chicano movement, with its emphases on la raza unida and carnalismo, introduced a semblance of peace and unity to the West and South sides of town.

The politicization of barrio youths would become a controversial matter in the late 1960s and early 1970s, commanding as much media attention as the gang wars of earlier years. The mobilization of angry working- and lower-class youths startled the established leadership of both the Anglo and Mexican American communities. Against a national backdrop of urban riots and increasing Black militancy, they worried about the signs of restlessness in the barrios. In the fifties and through the mid-sixties, the Anglo and Mexican American elites had guided San Antonio through a peaceful and gradual desegregation of city facilities and schools. A paternalistic arrangement had provided for some representation of Mexican Americans and African Americans on the city council and the school board. In 1961, San Antonio had elected Henry B. Gonzalez to Congress, another sign of the city’s moderate outlook on race and ethnic relations. Nonetheless, the Chicano movement, by drawing attention to the rather obvious class and race inequities in the city and state, posed a strong challenge to this paternalistic arrangement. In defense of this status quo stepped Congressman Gonzalez, the old “radical” of the desegregation battles of the 1950s. The political climate became ugly.

The controversy reflected an internal disagreement within the Mexican American community over how to advance politically, a disagreement that surfaced mainly along social class and generational lines. Middle-class Mexican Americans were alarmed by the threatening rhetoric of the youthful Chicanos. The “old guard” leadership feared that these radical college and barrio youths would introduce the polarizing dynamics of racial violence that had already spread from Watts in California to the northern cities. For their part, some young Chicanos fanned this fear at every opportunity, calling for the elimination of racist “blue-eyed gringos” by any means necessary.

This internal community conflict surfaced publicly in several dramatic incidents involving fisticuffs, public denunciations, death threats, police surveillance, congressional inquiries, college expulsions, arrests, and prison sentences. For the Mexican American community of San Antonio and South Texas, the six-year period from 1968 to 1973 was not one of marching together, but of “vitriolic divisions of charge and counter-charge, bite and bite back, physical walk-outs and emotional blow-outs.”3 As a result of this political drama, some common Mexican insults referring to machismo (manhood) or lack thereof, pendejos (idiots), and vendidos (sellouts) became regular breakfast fare for the English-reading public of South Texas. Newspaper coverage, particularly that of Paul Thompson, gadfly columnist for the San Antonio Express & News, provided regular interpretations of the unfolding conflict.

In the following chapters of Part One, I describe the Chicano movement, the manner in which the so-called gang youths became part of it, and the reactions that all of this provoked.

1 THE LEAKING CASTE SYSTEM

IN THE MID-SIXTIES, San Antonio was, in the words of one insightful observer, “a city of deference and racial differences; it was still a southern center.” San Antonio was “southern” in its segregation, even though the main racial divide was between Anglo and Mexican. The city’s population (587,718 in 1960) was 51 percent Anglo, 41 percent Mexican American, and 7 percent African American. By 1965, due in part to Anglo migration to outlying suburbs, San Antonio was well on its way to becoming a Mexican American majority city.1

The city’s racial neighborhood zones were plainly evident. The East Side was the Black side of town; the North Side was the Anglo side; and the West and South sides were considered the Mexican side of town. Despite some breeching of the walls, the boundaries of the Mexican side were clear in the mid-sixties: Culebra Street from Loop 410 across San Pedro Park to San Pedro Street formed the northernmost boundary; San Pedro Street through downtown, to its connection with Roosevelt, and Roosevelt as far as the Loop formed the eastern boundary; Loop 410 marked the western and southern boundaries of the Mexican side of town, nearly one-third of the city in the mid-sixties.

The stark segregation of this period was regularly commented on by outside observers. According to Leo Grebler, Joan Moore, and Ralph Guzman, a visiting social science team from UCLA, San Antonio appeared caste-like. However, because the rise of a new middle class among Mexican Americans had made the segregated order “somewhat less rigid,” they qualified their description and called it a “leaking” caste system. Sociologist Buford Farris likewise described the social relations between Anglos and Mexican Americans in the mid-sixties as a “model of two almost separate systems.” San Antonio, according to Farris, was a conflictual situation of “assimilation with resistance.” Anglos perceived “a separate political unity” of Mexican Americans to be the “largest threat” to San Antonio. Speaking Spanish was also considered a threat. Mexican Americans, on the other hand, expressed support for ethnic political unity and saw Spanish as “an emotional language.”2

Segregation was not just a question of separate systems, but of hierarchy and authority as well. Generally the only Anglos who entered the barrios were police officers, teachers, social workers, and bill collectors. Anglos were essentially individuals with authority. This was the gist of the testimony that seventeen-year-old Edgar Lozano, then a junior at Lanier High School, gave in 1968 when asked about the effects of segregated schooling on Mexican American students:

Well, that is the only people you know. I mean, if you have only known Mexican American people, as far as you are concerned, that is the whole world right there.

And then let’s say you move out of that part of town, or you go to another city, then you meet nothing but Anglos. I mean, you know, that is strange to you. You have never met this type of people, maybe only as your teacher or your boss, or something else. So, consequently you have an idea that they’re always—that they’re always your boss, your supervisor and they always dress better, nicer, and they always tell you what to do.3

Segregation, in other words, embodied a hierarchy of both race and class.

The hierarchy built on segregation also made itself felt on the Anglo side of town. At the very top, a “stodgy old guard,” as one observer described the city’s elite, kept firm reins on the citizenry and on any new economic developments. “Twenty families,” according to a former city manager, “ran San Antonio.” A developer who moved to San Antonio from Dallas in 1963 described San Antonio of that time as “a little kingdom run by a small group of people who controlled all commerce and development.”4 At the head of this “little kingdom” was Walter McAllister—businessman, founder of the oldest and largest savings and loan, longtime civic leader, and mayor from 1961 to 1971. McAllister was the “moving force” behind the Good Government League (GGL), organized in the early fifties to promote business interests as well as efficiency in government. As the instrument of the business-political elite, the GGL dominated San Antonio politics for nearly two decades. The at-large elections for nine city council seats favored the GGL, which had the resources to recruit and finance full electoral slates. From 1955 to 1975, seventy-seven of eighty races for city council were won by members of the GGL. As aptly described by Kemper Diehl and Jan Jar-boe, it was an “elitist” arrangement:

San Antonio was a town ruled by a small group of businessmen who worked in downtown banks and law firms, played tennis, golf, and poker at the San Antonio Country Club, and were well-organized politically under the auspices of the GGL. Yes, it was elitist.5

Despite segregation, San Antonio was considered a “moderate” southern city because the GGL had included token representation from the Mexican and Black communities on its city council slates since the mid-fifties. Selected by a secret nominating committee of the Anglo business elite, these “minority” representatives rarely lived in the Mexican or Black neighborhoods.6 Yet such token representation was a progressive step from the Jim Crow system of the 1940s, and it was emblematic of the paternalistic rule of San Antonio’s Anglo business-political elite.

Much pressure for change had come from the activism of the World War II and Korean War veterans and the rising middle class of the Mexican American community. Although the GGL had extended its influence through a “West Side” branch, the Mexican American community occasionally elected a few mavericks—Albert Peña, Joe Bernal, Pete Torres, and early in his career, Henry B. Gonzalez—and these individuals kept the city moving forward in improving race relations. Prodded by Gonzalez, then a city councilman, the city had officially desegregated its schools and public facilities in the mid-fifties. In 1963 San Antonio began a voluntary desegregation of privately owned but publicly used facilities. As Mayor McAllister would later testify (in 1968), of the 655 hotels, motels, and restaurants that were impacted, “all but two motels and one restaurant voluntarily agreed to integrate.” According to the mayor, a “spirit of tolerance in human relations” characterized the city of San Antonio.7

Paternalism rather than tolerance was a better description of the way the Anglo elite related to Mexican Americans at this time. County commissioner Albert Peña, a bitter critic of San Antonio’s political and social structure, described the top as “a very, very small group of San Antonians, old familie...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: The Conflict Within

- Part Two: Marching Together Separately

- Part Three: After the Fury

- Appendix: On Intepreting the Chicano Movement

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index