![]()

PART 1

The Functions and Meanings of Home

If a single theme runs through the thirty interviews in this collection, it is diversity—these architects, educators, and writers present a rich and eclectic range of opinions and approaches to the “American idea of home,” particularly and deliberately so in Part 1, which tackles what our homes mean to us and how we inhabit them. From the majestic work of Richard Meier to the small-is-better philosophy of Sarah Susanka, this section illustrates the many ways we can think about the subject.

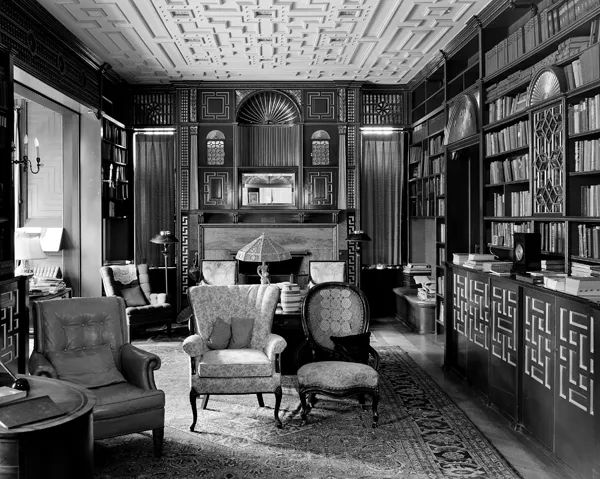

Library in the William Watts Sherman House. The interior of the nineteenth-century home was designed by Stanford White. It is at 2 Shepard Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island.

![]()

RICHARD MEIER

“Stanford White’s houses are famous and influenced a whole style of building in this country, especially in the East in the early part of the twentieth century.”

Long before Richard Meier (b. 1934) became an architect with the star power to command the largest institutional commissions, he had spent the better part of a decade pondering architecture on a residential scale. Meier established his private practice with a home designed for his parents in Essex Fells, New Jersey, in 1963. Several years later, his white-and-glass Smith House in Darien, Connecticut, propelled him onto the national stage. And by 1969, Meier—born in Newark, New Jersey, with a BA in architecture from Cornell in 1957—was named one of the “New York Five,” in a landmark meeting at the Museum of Modern Art.

Meier has received the Pritzker Architecture Prize and also a gold medal from the American Institute of Architects (AIA). While an ardent admirer of Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, he feels equally indebted to Italian Renaissance architects Donato Bramante and Francesco Borromini.

“Architecture is a tradition, a long continuum,” says Meier. “Whether we break with tradition or enhance it, we are still connected to that past.”

Meier’s largest and most visible commission is the $1 billion Getty Center in Los Angeles, California. There is also the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, High Museum in Atlanta, Frankfurt Museum for Decorative Arts, and more. But throughout, Richard Meier never stopped designing homes. His many residential commissions, like the elegant 2013 Fire Island House, have given him the liberty to create innovative structures using, as he puts it, “human dimensions as a unit of measure.”

Richard Meier begins our collection of conversations by addressing, among other things, the one variable that remains constant in residential architecture: “accommodating to and understanding of human scale.” It is a quality he admires in the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, an architect who has influenced most, if not all, the designers interviewed. Wright, according to Meier, had a profound understanding of “the way in which you move through and experience space.”

Which architects have influenced you the most?

Richard Meier: Probably the most influential residential architect, in terms of ideas, is Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright did more houses than any other architect I know of. And he had an enormous influence on people’s understanding of what residential architecture could be. Not that they followed Wright or designed like him, but the quality of Wright’s architecture is amazing, and that has to do with the quality of human scale and the way in which you move through and experience space. The spaces in Wright’s architecture were very small and confined, not like the huge mansions you see being built around the country today. They were refined and well-defined spaces, and they had a wonderful quality about them. When I think of Frank Lloyd Wright and all that he contributed to American architecture, it’s surprising that what we see today takes so little of his influence and uses it in a good way.

H. H. Richardson did some extraordinary residential work. Stanford White’s houses are famous and influenced a whole style of building in this country, especially in the East in the early part of the twentieth century.

Each era is different, and I think today people are interested in more openness, transparency, and freedom of movement than existed fifty or a hundred years ago in residential design. So today’s houses indicate a different way of living, with less maintenance. They set up a relationship between interior and exterior spaces that allows for ease of movement from inside to outside. And they are more responsive to the nature all around. Nature is ever changing—the color of the light changes throughout the day, the color of the season changes. But architecture is static, inert, and that creates a dialogue between the human made—architecture—and the organic and dynamic—the natural world.

What are your favorite styles of architecture?

Meier: My favorite style of American architecture is the style of the moment, which is contemporary architecture, modern architecture. It suits our way of living today in terms of our transparency and openness and in terms of its relationship to nature, the way in which the scale and the light are composed, experienced, and inhabited.

And pre-1900?

Meier: Pre-1900 there wasn’t much architecture in America. There was architecture in Europe; architects made palaces and large-scale residential works. But architecture is really a late-nineteenth- or twentieth-century phenomenon in this country. Up until the twentieth century, American architecture borrowed heavily from European styles, but it also had its own indigenous quality in terms of the work of architects such as Stanford White.

Do you think there is an American architecture today?

Meier: I don’t think there’s an American architecture, no. I think that the work you see in the United States is like the work you see in Tokyo or Shanghai or any other major city in which big architecture firms are practicing. In Berlin and Frankfurt, there are as many buildings by US firms as there are in major cities in America, and maybe even more so in places like Beijing. I don’t think there is an American architecture. American architecture has been exported to influence the rest of the world.

How has globalization changed architecture?

Meier: The speed of communication is such today that when a young architect in Argentina completes a work, it’s not only seen reproduced in publications in Argentina, but also in publications in America, Europe, and elsewhere. What’s interesting is that the quality of the workmanship and the materials used might be indigenous to Argentina, but they’re not foreign. The stonework looks like one would use stone in France or Minnesota. What may be lost is a recognition of place through the architecture.

Nevertheless, I think that certain parts of the world still maintain a regional architecture. If one thinks of residential work in Switzerland, for example, especially in the mountains, all the houses have pitched roofs, because the snow load would be too heavy for a flat roof. However, in other parts of Switzerland, you will see flat-roofed houses. So I think the international influences on the architecture depend a great deal on the particularities of a place.

Do you think regional architecture will die out completely at some point in the future?

Meier: I think that it depends on what region you’re talking about. Some regions of the world are very dependent on local customs, materials, and ways of building. Much of the residential architecture in the Middle East and Africa, for example, is made out of adobe—mud huts, as it were—because that’s what people can afford. In poor countries, the housing is often makeshift. It’s not really architecture; it’s what’s affordable.

Do you think the globalization of architecture is a good thing?

Meier: We live in a world culture. It’s the same with everything, not just architecture. The television programs that you watch at night are the same television programs that people in Abu Dhabi and Moscow watch, so it’s not as though our lives are so different. The physical and political climate we live in is different. But information travels at such a speed that regionalism and nationalism no longer exist as they once did.

In America, the kind of regionalism we saw earlier in the century is less prevalent today. A building in Michigan is not any different from a building in Louisiana or Texas. The styles of architecture have less to do with regional characteristics than they do with individual tastes and desires.

How has the relevance of the architect changed in recent years?

Meier: Culturally, there is a greater awareness of and interest in architecture and what good architecture is than there’s ever been before. I think this will continue, and as a result, the quality of our built environment will improve. People appreciate quality and are willing to go out of their way to experience it. For example, when we travel, what do we do? We go and look at architecture.

But when we think of the private residences that are built across our nation, a very small percentage is actually designed by an architect. I don’t know the exact figure, but the majority of homes are put up by developers as part of suburban subdivisions. One would like to think that architecture, when it’s good, influences even the work that is not done by architects. But I’m not sure that’s the case.

A lot of the houses designed by developers and contractors are based on older styles of American architecture.

Meier: In order to give people a choice, they’ll do a pseudo-Tudor house, pseudo-colonial house, pseudo-contemporary house, and God knows what else. But it’s just changing the front door appearance while keeping the same basic organization of the building.

How has technology affected residential architecture?

Meier: Architecture and technology probably have a greater relationship in larger-scale buildings—office, industrial, and commercial buildings—than they do in residential buildings. Residences are still, for the most part, built one at a time on a fairly small scale. Also, the building codes are such that houses can be built rather inexpensively when they’re made out of wood, whereas an industrial method of building is by and large more expensive. So I don’t think technology has been as important in residential architecture as it might have been. But it certainly has affected what goes into the house, in the mechanical systems, kitchen appliances, and sound and video systems. Technology has manifested itself in the things we use more than in the spaces we inhabit.

What things would you like to see change in architecture?

Meier: I would like to see more good architecture. There’s a lot of bad architecture, but it’s not something that one can change. It happens through education, appreciation, and awareness. I think New York is changing, for instance. The residential buildings are getting better because people realize they can make more money if they do a good building than if they do a mediocre building. Sometimes things change because of necessity, and sometimes things change because of economics or political interest. Cities like Shanghai change because the economy of the country has changed, creating a need for more and more work and residential space. Most cities that are viable and active undergo constant change. That’s one of the things that makes New York so fascinating.

What makes a successful house, and has that changed over time?

Meier: Architecture is a captivating subject, and people have been and will continue to be fascinated by other people’s homes. What happens in architecture today influences tomorrow, and people are constantly looking and thinking about how to change the way they live. But most importantly, the best residential work is that which is accommodating to and understanding of human scale. And that doesn’t change.

From the north porch of the Hill-Stead House, 35 Mountain Road, Farmington, Connecticut. The view takes in the Farmington Valley and Talcott Mountain range.

![]()

GRANT HILDEBRAND

“Well, refuge and prospect on the interior of the building is essentially a small space connected to a larger and brighter one. It gives an option between a cozy, reclusive space and a bright and expansive experience.”

Grant Hildebrand (b. 1934) is an architectural theorist. His writing explores how we derive pleasure from our homes by moving, for example, from a large space to a small space or vice versa. These transitions through diverse volumes create a sense of possibility—which is a key component of feeling innate pleasure. Hildebrand posits that our instinctual need for refuge feeds our pleasure response within a home. Why does a hillside home with a bucolic view give us deep comfort and satisfaction? It’s from the ancestral memory of having an entire range before us and the security of a cave behind, says Hildebrand.

Hildebrand is a professor emeritus of the Departments of Architecture and Art History at the University of Washington, where he received the university’s Distinguished Teaching Award in 1975. He holds a BA and MArch from the University of Michigan. His productive scholarly career includes numerous books, such as Origins of Architectural Pleasure (University of California Press, 1999) and The Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Houses (University of Washington Press, 1991).

Grant Hildebrand, who likes to look at architecture through the lens of anthropology, builds on the foundation laid by Richard Meier by discussing the need for variations of scale and illumination within a home—the need for both “refuge and prospect,” which triggers an emotional response in a home’s inhabitants. “We build a lot of houses now that are composed of a whole bunch of big rooms with fourteen-foot ceilings and vast amounts of space . . . but the cozy nook is of value as well as the drop-dead, two-story entry.”

An avid proponent of the need for us to downsize our living spaces, Hildebrand says with pride: “My wife and I live in 950 square feet . . . and we’re fine.”

In your book Origins, which proposes a theory about how human beings psychologically and physiologically relate to architecture, you use the words “prospect,” “refuge,” “enticement,” “peril,” and “complex order.” Please explain these terms.

Grant Hildebrand: Well, refuge and prospect on the interior of the building essentially mean a small space connected to a larger and brighter one. They give an option between a cozy, reclusive space and a bright, expansive experience. I could describe those things more deeply as part of our genetics or our human psyche, but just on the face of it, people like alternatives in the spaces they experience. The notion of enticement is the trail that disappears around the bend or the object we don’t quite see or that we want to discover. It’s a very powerful thing; I think we have an insatiable lust for knowledge and we seek it out. If that is presented in architecture—for example, the corridor that instead of proceeding straight bends a bit to some lit and interesting further experience—it interests us; it makes the building much more lively and intriguing, and this seems to persist over great lengths of time. People who have houses that have this quality sometimes will say they’ve lived there for years and continue to discover new things.

The idea of peril is trickier. I think we build Space Needles and Eiffel Towers to get that thrill and elation of being on the edge of danger. It’s a more rare thing. You don’t often find that in bu...