- 221 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A fascinating exploration of women's role in Roman religion that facilitates a better understanding of their importance in Rome's cultural formation.

Roman women were the procreators and nurturers of life, both in the domestic world of the family and in the larger sphere of the state. Although deterred from participating in most aspects of public life, women played an essential role in public religious ceremonies, taking part in rituals designed to ensure the fecundity and success of the agricultural cycle on which Roman society depended. Thus religion is a key area for understanding the contributions of women to Roman society and their importance beyond their homes and families.

In this book, Sarolta A. Takács offers a sweeping overview of Roman women's roles and functions in religion and, by extension, in Rome's history and culture from the republic through the empire. She begins with the religious calendar and the various festivals in which women played a significant role. She then examines major female deities and cults, including the Sibyl, Mater Magna, Isis, and the Vestal Virgins, to show how conservative Roman society adopted and integrated Greek culture into its mythic history, artistic expressions, and religion. Takács's discussion of the Bona Dea Festival of 62 BCE and of the Bacchantes, female worshippers of the god Bacchus or Dionysus, reveals how women could also jeopardize Rome's existence by stepping out of their assigned roles. Takács's examination of the provincial female flaminate and the Matres/Matronae demonstrates how women served to bind imperial Rome and its provinces into a cohesive society.

Roman women were the procreators and nurturers of life, both in the domestic world of the family and in the larger sphere of the state. Although deterred from participating in most aspects of public life, women played an essential role in public religious ceremonies, taking part in rituals designed to ensure the fecundity and success of the agricultural cycle on which Roman society depended. Thus religion is a key area for understanding the contributions of women to Roman society and their importance beyond their homes and families.

In this book, Sarolta A. Takács offers a sweeping overview of Roman women's roles and functions in religion and, by extension, in Rome's history and culture from the republic through the empire. She begins with the religious calendar and the various festivals in which women played a significant role. She then examines major female deities and cults, including the Sibyl, Mater Magna, Isis, and the Vestal Virgins, to show how conservative Roman society adopted and integrated Greek culture into its mythic history, artistic expressions, and religion. Takács's discussion of the Bona Dea Festival of 62 BCE and of the Bacchantes, female worshippers of the god Bacchus or Dionysus, reveals how women could also jeopardize Rome's existence by stepping out of their assigned roles. Takács's examination of the provincial female flaminate and the Matres/Matronae demonstrates how women served to bind imperial Rome and its provinces into a cohesive society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vestal Virgins, Sibyls, and Matrons by Sarolta A. Takács in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Roman Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

THE SILENT ONES SPEAK

Women have their uses for historians. They offer relief from warfare, legislation, and the history of ideas; and they enrich the central theme of social history. … Ladies of rank … are a seductive topic.

—RONALD SYME, THE AUGUSTAN ARISTOCRACY

Literature, a cross-section of genres, provides us with paragons and opposites of Roman womanhood. It is here that we encounter makers and destroyers of Rome, where we see women move outside the private, domestic sphere and enter the public arena. Some were harshly judged for their abandonment of family; others were not. All the judges were men, for it is their records we have, employ, and analyze. Literary examples make clear the distinctions between a respectable and disreputable Roman woman. The emphasis is on moral behavior, understood as the single most important factor for the proper functioning of society. Roman historical writing, in particular, demanded moralization and much hinges on the private/public category.

The most revealing literary evidence in regard to women and their actions taken for the benefit or detriment of Roman society often surfaces in accounts linked to transitional periods of Roman history. While Rome’s political structure remained that of a city, which was simply projected onto an expanding empire, the social and economic fabric changed rapidly. Romans and their gods formed a single community. Politics and religion were intertwined. Ancient societies were culturally more integrated than modern ones. Thus, unlike their modern counterparts, who try to step outside societal boundaries, ancient writers and artists were involved in representing and perpetuating their society and its norms. It is no surprise then that Latin writers relate a person’s or group’s moral failing or a religious ritual not properly executed as the single most important cause for social or political problems, regardless of how complex they might actually have been. One can make a case that this type of reductionism to simple sequences of cause and effect remained intact until the Enlightenment.

Moreover, Latin literature was very much a product of Rome’s self-definition vis-à-vis the much cherished Greek intellectual accomplishments. Decisive in the emergence of Latin literature was Rome’s success over Carthage, in particular, the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), which resulted in Rome’s hegemony over the Mediterranean World. Another such water-shed moment for Latin literature was the Age of Augustus (31 BCE), part of the so-called Golden Age of Latin literature (ca. 75 BCE–14 CE). Scholars have established and accepted it as the highpoint of literary achievement and the ultimate measure for anything literary before and after.1 But even more, Augustus’ reforms touched every aspect of Roman life. His marriage laws and religious innovations, for example, are at times interpreted as a reactionary attempt to return to true Republican values, which had been lost through the continued civil war period. Looking at the evidence, however, one can argue that Augustus’ attempt was a turning back to a fictitious past, a fiction that ultimately became a defining reality. Texts, which form the core of the study of Roman history, provide the potential of remembrance and temporal continuity. But the coherent whole, construed from various literary sources, is in fact inconsistent. It is the task of the modern historian to analyze these reporting and reflective, diverse, creative sources, as well as the material evidence, to discover a more complete picture and generate a better understanding of Rome.

BEGINNINGS

Rome’s beginnings are shrouded in myths. It is only with the fourth and third centuries BCE that historical information can be confirmed. The late Republican antiquarian Varro (116–127 BCE), writing the Antiquities Human and Divine, established the city’s founding date as April 21, 753 BCE.2 The most detailed account of the founding, however, we find in the first book of Livy’s historical narrative From the Foundation of the City. It so happened that for a time without any tangible literary data, writers produced highly detailed narratives. Artistic creativity found in myths, for example, material that was refashioned to form a cohesive historical narrative. Mythic and historical times that were fused together shaped, and still shape, our understanding of regal and early Republican Rome.

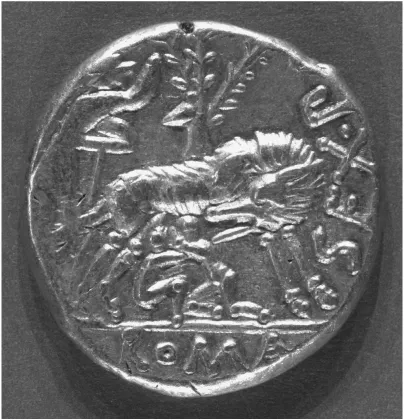

The twins Romulus and Remus were descendants of the kings of Alba Longa (Figures 1.1a, 1.1b). Ascanius Iulus is thought to have founded this city south of Rome. The connection between Troy, Alba Longa, and Rome became popular in the third century BCE. The myth of Aeneas was already known in Etruria in the sixth century BCE.3 In terms of historiography, it was the explanation recorded by the late fourth- and early third-century BCE historian Timaeus of Taoromena that placed the ever expanding central Italian power, Rome, into a Greek frame of reference; Rome’s foundation was connected to the most mythological and recognizable war of all history—up to that point—the Trojan War.4 Rome was linked to the world of Greek gods and heroes. Thus, the Greeks of Southern Italy and Sicily, versed in mythologies and stories of old, were able to explain away the unsettling fact that another group exerted control over them. In one swoop, with one good story, the Greeks eliminated the basic cultural differences between the conquerors and the conquered. Even better, the Roman elite integrated a Trojan hero into their earliest history, where, in fact, there had been no history at all. With this mythological connection, Rome’s cultural heritage was simultaneously Greek and not Greek in origin.

Aeneas, who was a minor figure in the Homeric epic cycle, escaped the burning Troy with his father Anchises perched on his shoulder. Aeneas also had with him his small son, Ascanius Iulus,5 and Troy’s household gods, the penates.6 Aeneas, son of the goddess Venus, displayed, under the trying circumstances of flight, profound pietas (piety) and virtus (virtue) toward his family and the state. Composing the epic around Aeneas and the foundation of Rome during the time of the first emperor, Augustus, Vergil focused on these and other ancestral customs, which are called the mos maiorum. These ancestral customs form an ethical framework, which Aeneas embodied. Crucial to Rome’s foundation myth is that Aeneas had to give up his personal wishes and desires for Rome to come about. Sometimes, the consequences of living or having to live in accordance with these mos maiorum strike us as heartless, yet setting aside the personal for the good of the state is a theme that will be encountered many times over in Roman history. It was a core principle that could, however, also be abused. Generals of the late Republic, Pompey or Caesar, for example, jockeying for power illustrate such breaches. Personal ambitions were cloaked as needs or remedies for a failing political system.

In Rome’s foundation women played an important, albeit tragic, role. While the family fled burning Troy, Creusa, Aeneas’ Trojan wife, fell behind. She eventually disappeared in the commotion that followed the fall of the citadel. Aeneas touchingly spoke of his wife when he related his story to his host, the queen of Carthage, Dido. Aeneas also told the queen of his encounter with the shade of Creusa, who foretold long travels and the establishment of a new home on the Tiber.

FIGURE 1.1A.

Roma depicted on Roman Republican denarius (obverse). Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, Sydenham 461 (a) = Crawford 235/1a.

Roma depicted on Roman Republican denarius (obverse). Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, Sydenham 461 (a) = Crawford 235/1a.

What use is it to indulge so much in frenzied sorrow, o sweet husband? Without the gods’ influence (numen) these things do not come about; nor is it divine law (fas) that you carry Creusa as your companion (comes) from here, since the ruler of high Olympus himself lets it be so. There is a long exile for you and plowing (arandum) through the vast expanse of the sea, and you will come to a western land, where Lydian Tiber flows in a gentle stream through rich fields of men. There will be apportioned for you things full of joy, kingship, and a royal spouse; stop crying for beloved Creusa. I will not gaze upon the proud home of the Myrmidones or of the Dolopians, nor will I enter into servitude to Grecian mothers, I a Dardan and daughter-in-law of divine Venus; but the great mother of the gods (magna deum genetrix) holds me back on these shores, but now farewell and protect the love of our common son.7

FIGURE 1.1B.

Wolf, Romulus, Remus with shepherd, depicted on Roman Republican denarius (reverse). Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, Sydenham 461 (a) = Crawford 235/1a.

Wolf, Romulus, Remus with shepherd, depicted on Roman Republican denarius (reverse). Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, Sydenham 461 (a) = Crawford 235/1a.

Vergil’s word choice here is significant. As comes (companion) connotes a superior (Aeneas) over an inferior-ranked person (Creusa) and infers a male-gendered context, coniunx (spouse, from con-iungere to join, yoke together) points to a more equal partnership. It is the partnership with Lavinia, the regia coniunx, through which Aeneas will receive regnum (kingship). Whatever has been, is, and will happen is ordained by divine law (fas). Aeneas will make it to Italy from the shores of Troy (Troiae … ab oris Italium … venit, Aen. 1.1–1.2), while the magna deum genetrix (the Great Mother of the Gods = Mater Magna of the Troad) kept Creusa from leaving the shores of Troy (his detinet oris). In addition to this internal connection, there is an external one that recalls Lucretius’ Venus genetrix in On the Nature of Things (De rerum Natura) and Catullus’ mater creatrix and genetrix of poem 63. Aeneas, the founder of the Roman people, is to plow (arandum from arare) through the sea; his descendants, the Romans, will be proud to be, first and foremost, farmers.

Aeneas was both anchored in the past (his duty: pietas) and bound to the future (his son and the kingdom to come). His personal wishes and desires were inconsequential. He was fated to become the founder of the Roman people. Although Aeneas loved the queen of Carthage, Dido, he had to leave her on the gods’ behest. Dido, abandoned by her lover and thus vulnerable to a world filled with former suitors, committed suicide. Shortly before dying, Vergil’s Dido uttered a curse and foreshadowed the turbulent relationship between Carthage and Rome, which, historically, were the three Carthaginian (or Punic) Wars.8 Once in Italy, the Trojan newcomers fought until Aeneas killed Turnus, a leader of an indigenous tribe, the Rutulians. Aeneas then founded a new city, Lavinium, named after his Latin wife, Lavinia. There the Trojan penates found a new home. Turnus’ killing, which forms the ending of Vergil’s epic, is disturbing but also signals to the reader that Rome was born in blood and that it came about and was defined by aggression and war.

Three women played crucial roles in Aeneas’ journey from Troy to Lavinium: Creusa, Dido, and Lavinia. Of the three, Dido was the most developed literary character and was portrayed as the most active. As a founder of a city, she not only was the equal of Aeneas but was also shown to be capable of negotiating politics and power, which were traditionally the sphere of men. While Dido outlined the area of a refuge for her and her followers, locals and envoys from surrounding cities urged the foundation of what was to become Carthage.9 In the Roman world of understanding, the act of founding a new city and delineating boundaries was a man’s business, and founders throughout Greco-Roman history were men of heroic stature. Leading magistrates were in charge of the religious ritual that marked the area where the new city was to stand. The furrow cut by a plow along the lines delineated by the augures (interpreters of auspices) was a religious line, the pomerium, within which the city had to be built.10 Only in this manner could a place be considered legally and religiously a Roman city. There is no record that Alba Longa, and subsequently Lavinium, was founded in this way, nor, in fact, Rome. Tradition, however, which came to determine Roman understanding of its history, emphasized that Rome was founded by augury and auspices.11 Rome’s success depended on its obligation to keep reciprocity between the world of humankind and that of the gods intact. The peace or harmony between these two worlds (the pax hominum and the pax deorum) was nourished by proper execution of religious rituals.12 Thus, Romans, whom the orator and statesman Cicero called the most religious of all people, would understand its political success in this context. As long as Romans worshiped their gods properly, Rome would be successful.

ROMULUS’ FOUNDATION

Rome’s beginnings were humble. Its legendary founders were twin boys, Romulus and Remus, born to a Vestal Virgin, Rhea Silvia, also known as Ilia. Her uncle Amulius usurped his brother Numitor and forced Ilia to become a priestess of Vesta.13 Ilia was fetching water from a spring in the sacred grove of Mars, where she was raped.14 Afterwards the rapist, a divine-looking man, revealed himself as Mars and prophesied that the twin boys she would bear would surpass all men. When Amulius discovered the reason the pregnant Ilia was unable to perform her official duties, he decreed that the unchaste Vestal Virgin and her sons be put to death. An old law advised that a Vestal who had transgressed was to be buried alive15 or thrown from the Tarpeian Rock, located at the southeastern part of the Capitoline hill.16 Ilia’s cousin, Antho, made a plea on her behalf, and the sentence was changed to solitary imprisonment. The twins were put in a wicker basket that was placed in the floodwaters of the Tiber River, which flowed down toward what was to become Rome.

As the floodwaters receded, the basket became wedged near to a fig tree. A she-wolf found the two babes and nourished them until a shepherd discovered them. Romulus and Remus grew up, became shepherds, and founded settlements on the Palatine and Aventine hills. The location, about fifteen miles up the Tiber from the sea in a volcanic area, provided many natural advantages, among them an excellent defensive position and access to fertile land and trade routes. Romulus, who slew his brother for scoffing at his city wall by jumping over it, became Rome’s first king.

To increase the population of his foundation, Romulus allowed outlaws to settle and, because there were no women, kidnapped Sabine women during the harvest festival of the Consualia. Titus Tatius led the Sabines in retaliation against Rome. He captured the Capitol thanks to the treachery of a certain Tarpeia, who was more interested in material goods than in the well-being of her country. When the Sabines asked her what she wanted as a reward for her information (the location of a secret passage way to the Capitoline), she answered: “What you wear on your left arms.” Tarpeia had her eye on the golden bracelets the Sabine wore, but the Sabines heaped their shields, which they held with their left hands, upon her. According to t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Silent Ones Speak

- 2. Life Cycles and Time Structures

- 3. The Making of Rome

- 4. Rome Eternal

- 5. Rome Besieged

- 6. Rome and Its Provinces

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Ancient Authors

- Appendix B: Timeline

- Appendix C: Maps

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index