- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

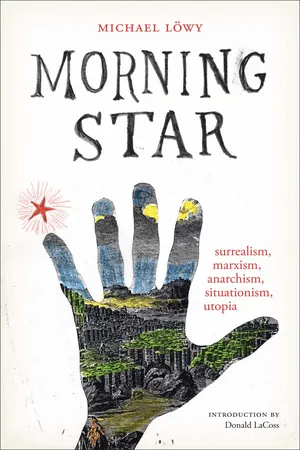

About this book

The acclaimed author of

On Changing the World examines the ways in which surrealism intersects with a variety of revolutionary political approaches.

In this expanded edition, the luminary critical theorist dismisses the limited notion of surrealism as a purely artistic movement, repositioning surrealism as a force in radical political ideologies, ranging from utopian ideals to Marxism and situationism.

Taking its title from André Breton's essay "Arcane 17," which casts the star as the searing firebrand of rebellion, Michael Löwy's provocative work spans many perspectives. These include surrealist artists who were deeply interested in Marxism and anarchism (Breton among them), as well as Marxists who were deeply interested in surrealism (Walter Benjamin in particular).

Probing the dialectics of innovation, diversity, continuity, and unity throughout surrealism's international presence, Morning Star also incorporates analyses of Claude Cahun, Guy Debord, Pierre Naville, José Carlos Mariátegui and others, accompanied by numerous reproductions of surrealist art. An extraordinarily rich collection, Morning Star promises to ignite new dialogues regarding the very nature of dissent.

Praise for On Changing the World

"His collection of essays, combining scholarship with passion, impresses by its sweep and scope." —Daniel Singer, author of Prelude to Revolution

"Michael Löwy is unquestionably a tremendous figure in the decades-long attempt to recover an authentic revolutionary tradition from the wreckage of Stalinism, and these essays are very often powerful examples of this process." —Dominic Alexander, Counterfire

In this expanded edition, the luminary critical theorist dismisses the limited notion of surrealism as a purely artistic movement, repositioning surrealism as a force in radical political ideologies, ranging from utopian ideals to Marxism and situationism.

Taking its title from André Breton's essay "Arcane 17," which casts the star as the searing firebrand of rebellion, Michael Löwy's provocative work spans many perspectives. These include surrealist artists who were deeply interested in Marxism and anarchism (Breton among them), as well as Marxists who were deeply interested in surrealism (Walter Benjamin in particular).

Probing the dialectics of innovation, diversity, continuity, and unity throughout surrealism's international presence, Morning Star also incorporates analyses of Claude Cahun, Guy Debord, Pierre Naville, José Carlos Mariátegui and others, accompanied by numerous reproductions of surrealist art. An extraordinarily rich collection, Morning Star promises to ignite new dialogues regarding the very nature of dissent.

Praise for On Changing the World

"His collection of essays, combining scholarship with passion, impresses by its sweep and scope." —Daniel Singer, author of Prelude to Revolution

"Michael Löwy is unquestionably a tremendous figure in the decades-long attempt to recover an authentic revolutionary tradition from the wreckage of Stalinism, and these essays are very often powerful examples of this process." —Dominic Alexander, Counterfire

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Morning Star by Michael Löwy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Art & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BREAKING OUT OF THE STEEL CAGE!

Surrealism is not, has never been, and will never be a literary or artistic school but is a movement of the human spirit in revolt and an eminently subversive attempt to reenchant the world: an attempt to reestablish the “enchanted” dimensions at the core of human existence—poetry, passion, mad love, imagination, magic, myth, the marvelous, dreams, revolt, utopian ideals—which have been eradicated by this civilization and its values. In other words, Surrealism is a protest against narrow-minded rationality, the commercialization of life, petty thinking, and the boring realism of our money-dominated, industrial society. It is also the utopian and revolutionary aspiration to “transform life”—an adventure that is at once intellectual and passionate, political and magical, poetic and dreamlike. It began in 1924; it continues today.

As the German sociologist Max Weber has written so forcefully, we are now living in a world that has become for us a veritable steel cage and confines us in spite of ourselves—a reified and alienated structure that imprisons us as individuals within the laws of the system of rationalism and capitalism as effectively as if we were inmates in prison. Surrealism is for us an enchanted means we can use to destroy the bars of this prison and regain our freedom. If, in the words of Weber, this civilization is the universe of Rechnenhaftigkeit—or the spirit of rational calculation—then Surrealism is a precise instrument that will allow us to sever the threads of this arithmetical spider’s web.

Too often, Surrealism has been reduced to paintings, sculptures, and collections of poetry. It certainly includes all these manifestations but in actuality it remains elusive, beyond the rational understanding of appraisers, auctioneers, collectors, archivists, and entomologists. Surrealism is above all a particular state of mind—a state of insubordination, negativity, and revolt that draws positive, erotic, and poetic strength from the depths of the unconscious: that abyss of desire and magic well—the pleasure principle—in which we find the incandescent music of the imagination. For Surrealism, this mental transformation is present not only in the “works” that are found in museums and libraries, but also and equally so in its games, strolls, attitudes, and activities. The Surrealist idea of drifting or aimless wandering (dérive) is a prime example.

To understand the subversive implications of dérive, let us return to Max Weber. The quintessence of modern Western civilization is, according to him, action with a rational purpose (Zweckrationalität), utilitarian rationality. This permeates every aspect of life in our society and shapes our every gesture, every thought, and every aspect of our behavior. The way individuals move about in a street is one example. Although they are not as ferociously regulated as red ants, nevertheless their movement is aimed almost entirely at reaching rationally determined goals. People are always going “somewhere,” they are in a hurry to take care of “business,” or they are on their way to work or their way back home. There is nothing gratuitous about this Brownian movement of the masses.

On the other hand, dérive, as practiced by the Surrealists and the situationists, is a joyous excursion completely outside the weighty constraints of that domain of utilitarian reason. As Guy Debord observed, people who are experiencing dérive “waive, for a longer or shorter period, their reasons for moving about and behaving as they usually do—let themselves be guided by the charms of the places they find and meetings they chance to have there” (Debord 1956).

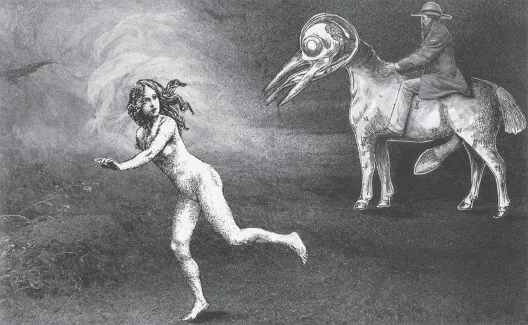

Eugenio Castro, untitled, 1996.

Albert Marencin, untitled, 1974.

In its playful and irreverent form, dérive breaks away from the most sacred principles of modern capitalism, with its iron laws of utilitarianism and the omnipresent rules of utilitarian rationality. It can become, thanks to the magical virtues of this point of absolute divergence, of leaving everything, an enchanted promenade through the domain of Freedom, with chance for its only compass.

In certain respects, dérive can be seen as a descendent of the idle strolling practiced in the nineteenth century. As Walter Benjamin observed in his Passagenwerk, the stroller’s laziness or indolence is “a protest against the division of labor.” However, contrary to the stroller, the “one who pratices dérive” is no longer held in thrall by commodity fetishism, the drive to consume—even though it is possible he might purchase a “found object” in a shop or enter a café. He is not hypnotized by the glare of shop windows and their displays but is seeking something else.

With no aim and no purpose [with no Zweck and no Rationalität]: two words that sum up the profound meaning of such a dérive, a practice that, in a single stroke, has the mysterious ability to restore the meaning of freedom for us. This experience of freedom produces a dizzy exaltation, a “state of transport.” It is an experience that reveals the hidden side of external reality—and also of our own inner reality. Streets, objects, passersby, freed suddenly from the iron laws of rationality, appear in a different light, become strange, disturbing, or sometimes comical. Sometimes they give rise to anxiety but also to jubilation.

As Guy Debord wrote, everything leads us to believe “that the future will speed up irreversible changes in behavior and the structure of contemporary society. One day, we’ll build cities to practice dérive in.” Though dérive may be an activity of the future, it is also the inheritor of an ancient, even archaic tradition—the seemingly random activities found in so-called primitive societies.

The Surrealist approach in terms of its lofty and bold ambitions is unique. It aims for nothing less than overcoming the reified oppositions whose expression has long found its actuality through its shadow-puppet theater, culture: dualisms of matter and spirit, exteriority and interiority, rationality and irrationality, wakefulness and dream, past and future, sacred and profane, art and nature. For Surrealism desires not merely a “synthesis” but the process that in Hegelian dialectics is referred to as Negation (Aufebung), the conservation of opposites, and the overcoming of them to attain a higher level.

As André Breton often stated, from his Second Manifesto of Surrealism to his last writings, the Hegelian-Marxist dialectic is at the heart of the philosophy of Surrealism. As late as 1952, in his book Entretiens, he left no doubt on the matter: “Next to Hegel’s method, all others are insignificant. For me, where the Hegelian dialectic does not operate, there is no thought or even hope of finding truth.”

Ferdinand Alquié was not wrong to insist, in his Philosophy of Surrealism, that there is a contradiction between Hegel’s historical reason and the lofty moral demands inspiring the Surrealists. But he does not take into consideration the distinction, already made by nineteenth-century Left Hegelians, between the (conservative) system and the (revolutionary) method of the author of the Phenomenology of Mind. Alquié’s attempt to replace Hegel and Marx with Descartes and Kant and to substitute transcendence and metaphysics for the dialectic misses the main points of Surrealist philosophy. Alquié himself recognized and regretted that “Breton was apt to emphasize the Hegelian structure of Marx’s analyses, to clarify and valorize Marx through Hegel.” He also recognized that the author of the Manifestoes of Surrealism always spoke against transcendence and metaphysics. But he chose to disregard the explicit content of Breton’s thought in the name of a very spurious interpretation of the “spirit” of his writings (Alquié 1977, 145).

The essays brought together here in Morning Star, whether their approach is historical or contemporary, aim to shed light on the continuing relevance of Surrealist ideas, values, myths, and dreams. The crimson and black thread that runs through them is the ever-burning question of revolutionary change. Since 1727, astronomers have defined a revolution as a body rotating around its own axis. Surrealists define revolution in exactly the opposite way. They see it as an interruption of the monotonous rotation of Western civilization around itself, to do away with this self-absorbed axis once and for all and to open the possibilities of another movement: the free and harmonic movement of a civilization of passional attraction. A utopia of revolutions is the musical energy of this movement (Surr 1996).

Most of these texts have been published in Surrealist journals, mainly in Prague, Madrid, and Stockholm. By including essays on some figures not directly belonging to Surrealism—but who drew part of their subversive force from it, such as Guy Debord—we aim to suggest links of “elective affinity” that can be drawn between Surrealism and other critical expressions of contemporary thought. A chapter deals with the continuation of Surrealism after 1969, the date of the attempt to dissolve the movement by a few who had been its prime movers (Jean Schuster, José Pierre, Gérard Legrand, etc.). The poet and essayist Vincent Bounoure, who died in 1996, spearheaded the continuation of the Surrealist adventure. His obstinate fight against the dissolution found an echo, not only in Paris but elsewhere in Europe and throughout the world. Today, collective Surrealist activity can be found in Paris, Prague, Chicago, Athens, São Paulo, Stockholm, Madrid, and Leeds.

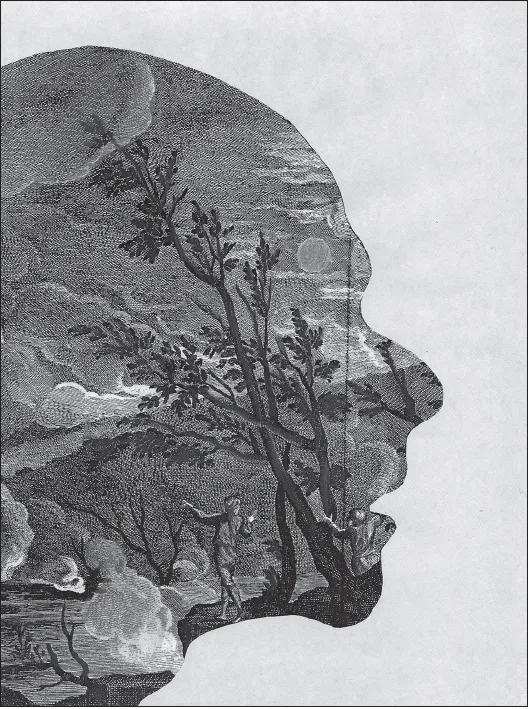

Michael Löwy, Paysage intérieur II (Interior Landscape II), 1998.

Most of the essays published here deal with the political philosophy of Surrealism and its relation to political thought. Surrealist identification with historical materialism, affirmed by Breton in the Second Manifesto, played a decisive role in the history of the movement, especially in regard to the political stands it took. We are familiar with the key points in this process; joining the French Communist Party in 1927; breaking with Stalinist Communism during the Conference in Defense of Culture in 1935; Breton’s visit to Trotsky in 1938; and the founding of the FIARI (International Federation of Independent Revolutionary Art).

And later, the rediscovery of Fourier and the utopians in the postwar period; the attempts at rapprochement with the anarchists in the 1949–1953 period; and finally, the Manifesto of the 121 for the right to refuse to serve in the Algerian war (1961) and active participation in the May ’68 events. During those years, the Surrealist group obstinately refused to support either the “Western World”—that is, the imperialist powers—or the so-called socialist camp—that is, Stalinist totalitarianism. This cannot be said of the majority of “politically committed” intellectuals.1

Anny Bonin, Marc de café: Triangles (Coffee Grounds: Triangles), 1998.

If many of the Marxist thinkers discussed in this book—such as Pierre Naville, José Carlos Mariátegui, Walter Benjamin, and Guy Debord—were fascinated by Surrealism, it is because they understood that this movement represented the highest expression of revolutionary romanticism in the twentieth century. What Surrealism shares with the early works of Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis, with Victor Hugo and Petrus Borel, Matthew Lewis and Charles Maturin, William Blake and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, is the intense and sometimes desperate attempt to reenchant the world. Needless to say, not through religion, as among many romantics, but through poetry. For the Surrealists, this practice is inseparable from the revolutionary transformation of society.

Pierre Naville has the distinction of being one of the founders of Surrealism and, a few years later, of the Left Opposition (Trotskyist). Although the time he spent in the Surrealist movement was relatively brief—1924–1929—nevertheless, he played a major role in turning Breton and his friends toward Marxism and political commitment. For Pierre Naville as for Walter Benjamin, the key meeting point and the most fundamental point of convergence between Surrealism and Communism was revolutionary pessimism.

Needless to say, such pessimism doesn’t mean resignation to misery: it means refusing to rely on the “natural course of history” or being prepared to fight against the current with no certainty of winning. These revolutionaries are motivated not by a teleological belief in a swift and certain triumph, but by the deeply held conviction that it is impossible to live as a human being worthy of that name without fighting fiercely and with unshakable will against the established order.

Similar ideas can be found in Le Pari mélancholique, a book by Daniel Bensaïd: radical political commitment is based not on any kind of progressive “scientific certainty,” but on a reasoned wager on the future. Daniel Bensaïd’s argument is impressive in its lucidity. Revolutionaries like Blanqui, Benjamin, Trotsky, or Guevara, he writes, have an acute consciousness of peril, a sense of the recurrence of disaster. Nothing is more foreign to the melancholic revolutionary than a paralyzing faith in inevitable progress and a guaranteed future. Although they are pessimists, they refuse to surrender, to give in. Their utopia is the principle of resistance to inevitable catastrophe (Bensaïd 1997).

If Marxism was a decisive aspect of the political itinerary of Surrealism—especially during the first twenty years of the movement—it is far from the only one. Since the movement’s inception, an anarchist, libertarian sensibility has run through Surrealists’ political thought. This is evident in Breton, as I indicate in one of the essays collected here, but it also holds true for most of the others.

Benjamin Péret is among those whose work radiates with the same dual light, at once crimson and black. Of all the Surrealists, he was without a doubt the most committed to political action inside the workers’ and Marxist movements, first as a Communist, then (during the 1930s) as a Trotskyist, and finally, in the postwar period, as an independent revolutionary Marxist. However, when he fought in the Spanish civil war, he chose to combat fascism by joining the ranks of Buonaventura Durruti’s libertarian column.

This dual light can also be seen in his political and historical writings. An interesting exampl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION: Surrealism and Romantic Anticapitalism

- 1. BREAKING OUT OF THE STEEL CAGE!

- 2. MORNING STAR: The New Myth from Romanticism to Surrealism

- 3. THE LIBERTARIAN MARXISM OF ANDRÉ BRETON

- 4. INCANDESCENT FLAME: Surrealism as a Romantic Revolutionary Movement

- 5. THE REVOLUTION AND THE INTELLECTUALS: Pierre Naville’s Revolutionary Pessimism

- 6. CLAUDE CAHUN: The Extreme Point of the Needle

- 7. VINCENT BOUNOURE: A Sword Planted in the Snow

- 8. ODY SABAN: A Spring Ritual

- 9. CONSUMED BY NIGHT’S FIRE: The Dark Romanticism of Guy Debord

- 10. INTERNATIONAL SURREALISM SINCE 1969

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX