- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A "well-organized and interesting" overview of science in the Muslim world in the seventh through seventeenth centuries, with over 100 illustrations (

The Middle East Journal).

During the Golden Age of Islam, in the seventh through seventeenth centuries A. D., Muslim philosophers and poets, artists and scientists, princes and laborers created a unique culture that has influenced societies on every continent. This book offers a fully illustrated, highly accessible introduction to an important aspect of that culture: the scientific achievements of medieval Islam.

Howard Turner, who curated the subject for a major traveling exhibition, opens with a historical overview of the spread of Islamic civilization from the Arabian peninsula eastward to India and westward across northern Africa into Spain. He describes how a passion for knowledge led the Muslims during their centuries of empire-building to assimilate and expand the scientific knowledge of older cultures, including those of Greece, India, and China. He explores medieval Islamic accomplishments in cosmology, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, geography, medicine, natural sciences, alchemy, and optics. He also indicates the ways in which Muslim scientific achievement influenced the advance of science in the Western world from the Renaissance to the modern era.

This survey of historic Muslim scientific achievements offers students and other readers a window into one of the world's great cultures, one which is experiencing a remarkable resurgence as a religious, political, and social force in our own time.

During the Golden Age of Islam, in the seventh through seventeenth centuries A. D., Muslim philosophers and poets, artists and scientists, princes and laborers created a unique culture that has influenced societies on every continent. This book offers a fully illustrated, highly accessible introduction to an important aspect of that culture: the scientific achievements of medieval Islam.

Howard Turner, who curated the subject for a major traveling exhibition, opens with a historical overview of the spread of Islamic civilization from the Arabian peninsula eastward to India and westward across northern Africa into Spain. He describes how a passion for knowledge led the Muslims during their centuries of empire-building to assimilate and expand the scientific knowledge of older cultures, including those of Greece, India, and China. He explores medieval Islamic accomplishments in cosmology, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, geography, medicine, natural sciences, alchemy, and optics. He also indicates the ways in which Muslim scientific achievement influenced the advance of science in the Western world from the Renaissance to the modern era.

This survey of historic Muslim scientific achievements offers students and other readers a window into one of the world's great cultures, one which is experiencing a remarkable resurgence as a religious, political, and social force in our own time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Science in Medieval Islam by Howard R. Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Science History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Islam as Empire

Islam as Empire

Within three years of the death of the Prophet Muhammad in AD 632, Arab armies, having secured control of Arabia in the Prophet’s name, began advancing beyond their peninsula into territories long ruled by the Byzantine and Sasanid empires. Led by the earliest Muslim caliphs, the spiritual and political leaders who succeeded Muhammad, Muslim forces spread out explosively in all directions. They had conquered Syria, Iraq, and Jerusalem by 637, Egypt by 642, Central Asia and western North Africa by 670. Less than fifty years later the armies of Islam had invaded Spain, Persia, and India and were conducting raids across the Pyrenees. In the west their advance was finally brought to a halt in 732 near Poitiers, in what is now France, by an army under Charles Martel, king of the Franks and grandfather of Charlemagne.

Within a single century Muslims had conquered not only much of the Middle East, North Africa, and the Iberian peninsula but also parts of the Indian subcontinent. The foundation of a great empire had been established throughout lands that stretched nearly six thousand miles between the Atlantic and Indian oceans. During the fourteen centuries that followed, the outside boundaries of this empire advanced in a few areas and retreated in many others. The political empire itself split into two, three, then many caliphates, each one the equivalent of a principality. These independent domains eventually shrank, were absorbed, or disappeared. Ultimately imperial Islam came to abandon much of its political identity and almost all of its independence. But long before this decline occurred—and for nearly half a millennium—Muslim caliphs ruled over lands, peoples, and resources that rivaled in extent those controlled by imperial Rome at its own zenith seven centuries earlier.

Early Muslim conquests were accelerated by the weakened condition of the Byzantines and Persians, long afflicted with political oppression, dissension, and widespread civil disarray. Perhaps the times invited some new and compelling force, idea, or spirit. Such was forthcoming. The religious zeal of Muhammad’s followers, the strengthening bonds of their new faith, their commanders’ capabilities of leadership, and their soldiers’ concerted military skills, superior to those of opposing tribal groups, were all crucial factors in the Muslims’ conquests as they expanded both eastward and westward. The forces opposing the Muslim armies could not match the conquerors’ superior strategies of attack, which derived in good part from the desert environment out of which the early armies had come and which featured the camel as basic and rapid transport.

The Arabs whose battalions spread so far and so fast belonged to a desert society long composed of farmers and nomadic shepherds, as well as a variety of merchants and commercial traders. The traditional business of this society lay in exchanging agricultural products, textiles, gold, and spices; its markets were strategically situated along the major trade routes that crisscrossed Arabia and linked it with neighboring regions on the East African coast and with India across the Arabian Sea. The rapid course of the Muslim advance across much of the Near East, North Africa, and the Iberian peninsula calls to mind the kind of carefully planned grand strategies that guided the invasion of Europe by the Allied force during the Second World War. However, the Muslims do not appear to have projected any specific agenda, let alone a timetable, for their conquest of the vast areas they ultimately won. Their initial successes impelled them to keep going. Their leaders may have heard tales of the richer lands, bigger harvests, and fabulous treasure that lay still further ahead, greater than any known in the parched environment of the Arabian heartland. Desire for the valuable fruits of conquest, however, was secondary to the driving force of what was in good part a religious and political crusade.

Muslim success in getting one vanquished population after another to accept and serve their new rulers was made easier by the long-deprived condition of so many of the people in the occupied lands and by the relatively benevolent requirements of the occupiers. Muslim rule was generally less harsh than that of previous invaders. Christians and Jews were not required to convert if they paid suitable tribute; they were also freed from obligatory (and dreaded) military service. Of course, the many sects of pantheists and pagans still risked the death penalty if they refused to pay tribute and refused conversion as well, although punishment came to be applied less rigorously in inaccessible areas.

Established on the foundation of a clearly defined but not entirely inflexible hierarchy of rulers and ruled, Islam as Empire evolved through some twelve centuries, rarely achieving political unity or equilibrium for long periods. The Prophet Muhammad, founder and head of the first Muslim state, was succeeded by four caliphs, three related to him by marriage. This group, known as the orthodox caliphate, ruled until 661, when a new and very different era began. From that point followed nearly twelve centuries of dynastic and political maneuvering and strife, including periodic war, between 1095 and 1291, with Christian crusaders.

Often overlapping in time, sometimes existing side by side, some thirty dynasties emerged, flourished, declined, and expired, their course marked by intermittent shifting of boundaries and loyalties. Between the seventh and thirteenth centuries arose the great medieval Arab dynasties: the Umayyads, with their capital at Damascus; the Abbasids, centered at Baghdad; the separate Umayyad dynasty that flourished in Spain; and the Fatimid dynasty of Egypt and northwest Africa. Together these regimes brought about the first great flourishing of Islam as Civilization. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, this young civilization faced the great challenges of Christian crusaders, migrating Turks from the Eurasian steppes, and the invading Mongols from Central Asia led by Genghis Khan and his successors. These incursions by other, different societies with unique cultures of their own profoundly affected the character and evolution of Islamic society and particularly of the later Muslim dynasties that flourished after the thirteenth century, most notably the Mamluks in Egypt, the Ottomans in Turkey, the Safavids in Persia, and the Mughals in India.

Rich achievement in the arts and sciences marked virtually all of the great Muslim dynasties and imperial regimes. The expanse of Islamic culture that by the sixteenth century extended as far as Southeast Asia had become vastly diversified even as it retained its Muslim core. The evolving relationship between the culture’s Islamic core and its many diverse regional ways of expression was to be Islamic civilization’s most distinctive characteristic as it moved on to the threshold of modern times.

Such was the broad geographical and historical stage on which the artists, philosophers, and scientists of the Islamic world produced their work. To understand the character, extent, and quality of their scientific efforts, in particular, one should first consider the forces of intellect that inspired and maintained them.

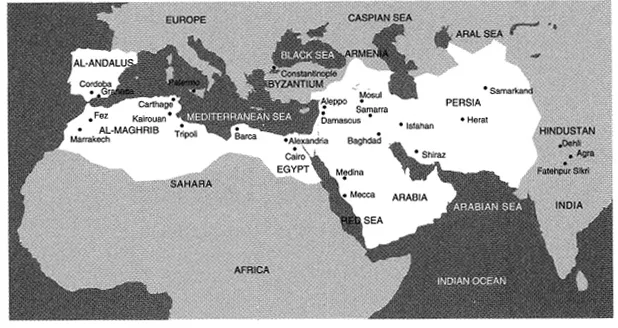

Figure 1.1

The Early Expansion and Major Centers of Historic Islam

The Early Expansion and Major Centers of Historic Islam

The white area on the map indicates the extent of the Islamic domain, or caliphate, in AD 750, following its first rapid expansion. While there is not much difference between the overall territorial size of the ancient Roman and medieval Islamic domains at their greatest extent, the differences in governance were profound. At its peak all of Rome’s empire was ruled by one emperor, and he could apply the system of civil law that he had inherited much as he chose. In the seventh century AD, after the reigns of the first four caliphs who succeeded Muhammad as head of state, Islam was ruled at any given time by as many caliphs as there were politically independent dynasties. But these rulers could not effectively place themselves above Islamic law, which, in good part, had been defined in Islam’s holy book, the Qurʾan, as well as in the teachings of the Prophet and of the orthodox schools of law. Apart from the Iberian peninsula, Sicily, and the Muslim lands of Southeast Asia, the areas dominated by Islam today are much the same as those inhabited by the Muslims at the height of the early empire, between the ninth and the eleventh centuries.

2

Forces and Bonds

Forces and Bonds

FAITH, LANGUAGE, AND THOUGHT

Islam as Faith

Around the year AD 610, Muhammad, a successful trader and prominent citizen of the town of Mecca in Arabia, received a revelation from God while meditating in a cave. Delivered through the angel Gabriel, the heavenly message directly challenged local and traditional pantheistic beliefs with a broad range of spiritual and social concepts and commands that were, in part, parallel to tenets of both Christianity and Judaism. Thus was born a new faith, based on belief in one supreme and all-powerful God before whom all were equal and to whom all must submit. The word Islam itself reflects this commitment on the part of all true Muslims: it means “submission.”

As a religion, Islam shares certain fundamental elements with the other two great monotheistic faiths, howsoever they vary in form and practice. Islam’s holy scripture, the Qurʾan, containing God’s message to Muhammad, has its counterparts in Judaism’s Torah and Christianity’s Bible. All three religions venerate the city of Jerusalem as the site of momentous events and the location of sacred monuments marking their history. All three emphasize fundamental phenomena: revelation, final judgment, and salvation. All consider history as imbued with divine purpose.

The youngest of the three religions, Islam respects important elements in Judaism and Christianity. The Qurʾan gives Abraham, Moses, and Jesus high and honored status as earlier prophets, and it venerates Abraham as the spiritual ancestor of all monotheistic worshipers. These and other shared beliefs in no way disguise or dilute the special or unique characteristics that set Muslim doctrines apart from those of Judaism and Christianity. Muslims hold that Islam is not only a continuation of the Judeo-Christian religious heritage but also an essential and comprehensive correction of its message. Muslims honor Muhammad as the most recent addition to the roster of the great prophets; they believe him to be the final messenger of God.

The fundamental doctrine of the Islamic Revelation defines the nature of God, the role of Muhammad as God’s messenger, the Qurʾan as the word of God, the hierarchy and function of Islam’s angels, the categories of sin, and the final day of judgment. Five acts of worship, or duties, are required of all Muslims: known as the Five Pillars, they include the profession of faith, daily prayers, almsgiving, fasting during the month of Ramadan, and, if possible, pilgrimage to Mecca once in a lifetime. Islam possesses no single, “official” church organization; in fulfilling religious obligations, each Muslim is essentially alone in the presence of God, without the mediating forms of priests and sacraments such as those found in Christianity.

Written down after Muhammad’s death in the form of Islam’s holy book, the Qurʾan (Al-Qurʾan, meaning “recitation” or “reading”), the Islamic Revelation represents, for devout Muslims, more than a set of religious beliefs and a system of worship. Together with the written record of actions or sayings attributed to Muhammad, known as hadith, the writings of the Qurʾan set forth fundamental Muslim religious thought. They proclaim God’s purpose: to make humankind responsible for its own actions and to place each person on earth to manage its affairs prior to finding his or her destiny in the world beyond. In providing an established form of what Muslims consider the final, perfect revelation, the Qurʾan also provides a broad range of rules covering not only religious practices but also most other phases of daily life, from family relationships and personal matters of social and sexual behavior, to proper dress, eating habits, hygiene, and the conduct of business and community affairs.

Within half a century after Muhammad’s death, a fierce conflict concerning the succession of Islam’s religious leadership split Muslim believers into two major sects, Sunni and Shiʿite. This division has endured throughout the centuries, with Sunnis claiming about four-fifths of all Muslims living today. Shiʿites predominate only in Iran and Iraq, although they are also found in regions of Syria, Lebanon, Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, and in some of the neighboring Gulf states. Over the centuries the Islamic faith has come to be practiced with variations in interpretation and ritual. Both Sunni and Shiʿite groups long ago embraced believers who adopted the doctrines and practices of Sufi mysticism. These activities are designed to help the worshiper achieve more direct and immediate communion with God through prayer, meditation, the singing or recital of devotional texts, and, within one order, ritualistic dervish dancing. The various sectarian differences have not weakened fundamental beliefs shared by all Muslims, nor did the Sunni-Shiʿite controversy hinder the rapid conquest of west and east in the century after the Prophet’s death.

The desire to find a better life than was possible amid the harsh struggle for existence in the Arabian heartland, as well as the lure of the spoils of conquest, might not in themselves have inspired the early and rapid growth of the Islamic empire, nor could these motives alone have long sustained vigorous Muslim rule of such a vast territory. Islam’s faith was a fundamental factor in accomplishing these epic feats. At the outset, the Muslim concept of jihad—better translated as “effort” or “struggle” (for the Faith) than simply as “holy war”—helped to drive Islam’s forces. But jihad, seen as large-scale, militant struggle to advance the Faith, rarely received consistent support from Islam’s leaders, especially in later centuries, when it often came to be perceived as an impractical ideal and was abandoned as an immediate option. In the Arabic-speaking world today, the term is often used to denote personal struggle to keep passion or desire under control.

What soon became the pivotal empire-building force was the generally rational, just, and humane Muslim approach to the rule and civil management of conquered territories, an approach that reflects precepts clearly set forth in the Islamic Revelation. All in all, Islamic rule encouraged cooperation on the part of local populations. Conversion became widespread in many areas, and for many people it meant less interference in their daily life than they had been accustomed to as non-Muslims or as subjects under Byzantine or Sasanid rule. Muslim law was derived from fundamental Qurʾanic doctrine, and as such tended to promote order and justice in the daily management of city, town, and village affairs. About a third of the Qurʾan’s six thousand verses deal with matters of practical legislation. Within a framework of ordained universal brotherhood and individual equality, the Islamic holy book prescribes mutual help as a legal duty, proscribes useless consumption as a sin, and defines moderation in all things as an essential goal. Keeping personal pledges, exercising individual or group rights, seeking conciliation and compromise, shunning reprisal: all are demanded. Islamic law, like the faith it both reflects and defends, was from the beginning conceived to impart to each Muslim enough knowledge of his or her obligations and rights to maintain “right conduct” in this world while preparing for life in the next, thus carrying out God’s will.

From the outset, within Muslim borders Christians and Jews who chose to pay the required tribute, thus retaining the right to follow their own beliefs, benefited from their special category as “people of the book.” They were regarded by Muslims, respectful of the Bible and the Torah, as sharing parts of the same spiritual message received by followers of Islam and the Qurʾan. At various times some Muslims have held that the world community is split into two hostile groups, believers (Muslims) and non-believers. Of course, parochial concepts of this sort have flourished in all eras and within most great religious, ethnic, and national communities. In any event, such prejudice did not deter Muslim empire-builders from achieving spectacularly advanced levels of civilization wherever they stayed long enough, whether in Spain, in India, or in between. Furthermore, the Islamic empire at its peak embraced a population that was more ethnically and culturally diverse, as well as socially stable, than the people of earlier or later empires such as those of Rome and imperial Russia.

During the early centuries of Islam’s empire, the religious and political community—the Arab word is ummah—was considered by Muslims to be the center of existence, recognizing its possession of God’s truth and acceptance of Shariʿa, God’s law. For several centuries notable travelers and other worldly scholars ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Epigraph

- Foreword and Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Islam as Empire

- 2. Forces and Bonds: Faith, Language, and Thought

- 3. Roots

- 4. Cosmology: The Universes of Islam

- 5. Mathematics: Native Tongue of Science

- 6. Astronomy

- 7. Astrology: Scientific Non-science

- 8. Geography

- 9. Medicine

- 10. Natural Sciences

- 11. Alchemy

- 12. Optics

- 13. The Later Years

- 14. Transmission

- 15. The New West

- 16. Epilogue

- Islam and the World: A Summary Timeline

- Glossary

- Works Consulted

- Illustration Sources

- Index