![]()

Chapter 1

COLOR THEM BLACK

Oh, we can beat them, forever and ever. Then we could be heroes just for one day.

—DAVID BOWIE, “Heroes”

Ain’t no such thing as Superman.

—GIL SCOTT-HERON, First Minute of a New Day

Scores of readers have used superhero comics to vicariously defy gravity and bound over skyscrapers, swing through the Big Apple with the greatest of ease, stalk the dark streets of Gotham, or travel at magnificent speeds throughout the universe on an opaque surfboard. Yet superheroes are more than fuel for fantasies or a means to escape from the humdrum world of everyday responsibilities. Superheroes symbolize societal attitudes regarding good and evil, right and wrong, altruism and greed, justice and fair play. Lost, however, in the grand ethos and pathos that superheroes represent are the black superheroes that fly, fight, live, love, and sometimes die. In contrast, even the most obscure white superheroes are granted an opportunity to make their way from the narrow margins of fandom to mainstream media exposure. (Remember the film Swamp Thing [1982]?) Nevertheless, what black superheroes may lack in mainstream popularity they more than match in symbolism, meaning, and political import with regard to the cultural politics of race in America. Even the omission and chronic marginalization of black superheroes are phenomena rife with cultural and sociopolitical implications.

The lack of black superheroes has served as a source of concerned speculation and critique. Arguably, Kenneth Clark’s groundbreaking yet flawed doll experiment from the 1950s is a theoretical cornerstone for the racial anxiety associated with an absence of black superheroes and its impact on both black and white children. Clark’s work revealed that when given a choice black children overwhelmingly preferred a white doll to a black doll and often associated negative qualities with the latter. This racial preference was taken as evidence that racial segregation contributed to internalized feelings of inferiority on the part of black kids.1 The results also implied that black children needed “positive” black images to help counteract low self-esteem. Against this theoretical backdrop the need to create black superheroes for black children to identify with takes on greater significance as a social problem. On the one hand, black superheroes are needed to counteract the likelihood of black children detrimentally identifying with white superheroes. On the other hand, the glut of white superheroes could encourage white children to accept notions of white superiority as normal.2 This type of racial logic is clearly on display in Frantz Fanon’s psychoanalytical manifesto on race Black Skin, White Masks (1952). In this book he argued that figures like Tarzan the Ape Man reinforced real racial hierarchies by repetitively depicting whites as victors over black people and chronically portraying blacks as representatives of the forces of evil.

A similar suspicion is detected in the Black Power aesthetic of singer and spoken word artist Gil Scott-Heron. On his album First Minute of a New Day Scott-Heron echoed Frantz Fanon’s trenchant critique of white superheroes with the terse edict, “Ain’t no such thing as Superman.” The statement subverts and calls attention to the racial implications embedded in Superman as one of the most iconic figures in American pop culture. In this case, a virtually indestructible white man flying around the world in the name of “truth, justice, and the American way” is not a figure black folk should waste time believing in. Gil Scott-Heron was signifying the dubious racial politics of having a strange and powerful white man presented as a figure of awe and wonder. Such a sensibility casts Superman’s identity as having less to do with being the last son of Krypton and more to do with symbolically embodying white racial superiority and American imperialism.

In contrast to the concern over the normalization of white supremacy in comics, Fredric Wertham accused the entire comic book industry of being a nefarious influence on American youth of all colors. He pronounced that the graphic depictions of violence, suggestive sexuality, fascist ideology, and homosexual innuendo woven into the images and narratives found in crime, horror, and superhero comic books had negative effects on children and were subversive.3 Wertham’s staunch opposition to comics was eventually successful. By 1954 the comic book industry had succumb to pressure and adopted a content code to mute vocal critics of the medium and placate public concerns that comics were dangerous because they contributed to juvenile delinquency.4 The code was put in place to protect readers from subversive and upsetting material even though it was predicated on disputed media-effects theories.5 In fact, the emergence of American youth as a significant consumer market and the increasing packaging of adolescent desire as an advertising method are likely stronger forces for cultivating behaviors, desires, and ideas than what is presented in comic books.6

Ultimately the fear about media effects on black children that admire white superheroes is overly simplistic and fails to seriously take into account the fact that audience reception is a more complex phenomenon than is suggested by a strict stimulus-response model of media consumption.7 For example, Junot Díaz, the author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, in his youth identified with the white mutant superhero team the X-Men. Because the group were mutants and were treated as social outcasts, as a young Dominican immigrant, Díaz felt an affinity for the characters due to his own marginalized racial status that stigmatized him as an outsider to mainstream America.8 Díaz’s experience speaks to the power of superheroes to deliver ideas about American race relations that stand outside of strict notions of authorial intent and draconian concerns about white superheroes (or black ones, for that matter) depositing negative notions about one’s racial identity into the reader or viewer. Consequently, even though superhero figures are predominantly white guys and gals clad in spandex and tights, a strict racial reading of the negative impact white superheroes may have on blacks is too linear and reductive.

Díaz’s anecdote also demonstrates how easily entertainment media and the cultural politics of race can converge in an interesting way. Yet the connection between the two realms was not clearly perceived or seamlessly integrated until the late 1960s and early 1970s. During this period the bright line between the popular and the political was obliterated as American pop culture began to shed its escapist impulses and boldly engage the racial tensions that America was experiencing. For example, James Brown’s song “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” (1968) did double duty as a dance hit and a racial anthem of uplift and self-esteem. A more subtle but just as powerful illustration of the intersection of the popular and the political regarding race occurred on Sesame Street, the pioneering public-television show for children. In the early 1970s Kermit the Frog was one of the show’s central characters, and when he sang a lament about how difficult it was being the color green the vignette clearly placed racial prejudice in the center spotlight. Even the most innocuous forms of American pop life were getting in on the trend. In 1971 Coca-Cola would launch a successful television ad campaign in which a multiracial throng of young people stood on a hilltop and sang the catchy jingle “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (in Perfect Harmony).” On one hand, the commercial could be criticized as the pinnacle of pop drivel for an unsophisticated public to mindlessly consume. On the other hand, by presenting an image of blacks, whites, and third-world people of color peacefully standing together singing in unison the commercial was a striking symbolic counterpoint to anxiety over racial unrest at home and the Vietnam War abroad.

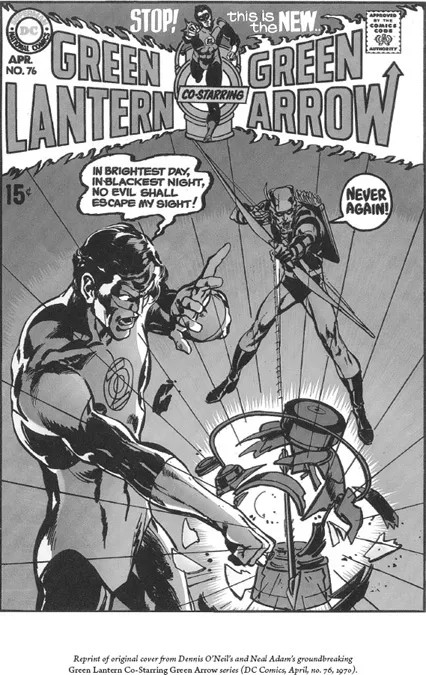

Arguably the turn toward increasing racial and political relevance in American pop culture was spurred by the baby boomer generation coming of age at the height of American racial unrest and political turmoil. The formulaic and commercial appeal of traditional forms of American pop culture faced severely diminishing entertainment value for the baby boomers. Bloated musical spectacles like On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970) were virtually ignored, westerns with their high-noon shootouts and sanitized violence were replaced by operatic depictions of bloodshed in spaghetti westerns, and a blaxploitation movie craze provided a new round of two-dimensional black characters that misled many to believe that racial diversity and the Hollywood film industry were synonymous. Alongside these multiple shifts in content and style, superhero comics also experienced a profound transformation. Marvel Comics was first to adjust. The paradigmatic “perfect” superhero was recreated as emotionally flawed and conflicted, a sensibility that mirrored the adolescent angst and ideological identity crisis that had taken hold throughout America as the turbulent 1960s gave way to the early 1970s.9 Reluctant superheroes such as Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, and the Incredible Hulk represented a new typology of superhero: troubled, brash, brave, and insecure. Not to be outdone, however, were the subsequent reimagining of DC Comics’s Green Arrow and Green Lantern.

Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams’s Green Lantern Co-Starring Green Arrow (1970–1972) comic book series dramatically recast superheroes, and shaped the superhero comic book as a space where acute social issues were engaged. On one hand, Green Lantern embodied President Richard Nixon’s no-nonsense dictum of “law and order” in the face of race riots and student protests. On the other hand, Green Arrow was the symbolic representative of activist youth, the working class, and the oppressed. Over at Marvel Comics, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby successfully tampered with the makeup of the superhero. In contrast, Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams changed the nature of the superhero genre by erasing the boundaries of what comics could discuss to such an extent that it had an impact on the genre for decades.

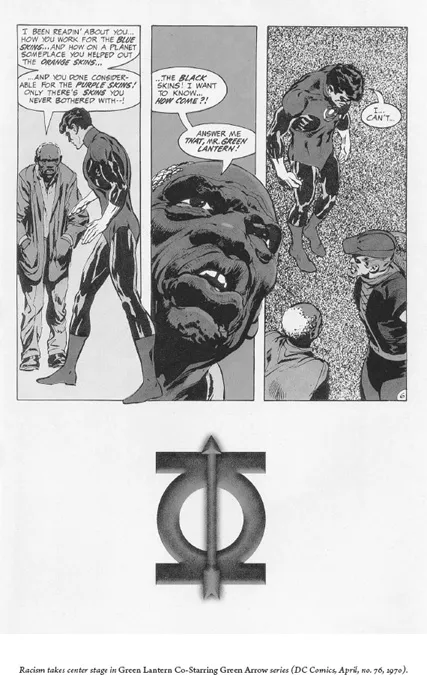

Prior to O’Neil and Adams, superheroes were quite predictable in that they mainly battled intergalactic threats or various types of villains committed to the most grandiose schemes often involving a quest for global domination. What made Green Lantern Co-Starring Green Arrow unpredictably complicated was that a significant part of the stories addressed topical and pressing social issues: poverty, racism, overpopulation, and drug abuse. The comic symbolically pitted the conservative politics of the “law and order” elites against the “Age of Aquarius” idealism of youth activists that championed changing the world by challenging the status quo. The magnitude of the social issues Green Lantern and Green Arrow confronted along with the audaciousness of having make-believe figures confront real and troublesome social issues turned the superhero tandem into charismatic characters and politically charged symbols. In the inaugural issue, “No Evil Shall Escape My Sight,” the pair confronts American racism. Across several panels an elderly black man is depicted questioning Green Lantern’s commitment to racial justice when he voices this short soliloquy, “I been readin’ about you . . . How you work for the Blue Skins . . . and how on a planet someplace you helped out the Orange Skins . . . and you done considerable for the Purple Skins! Only there’s skins you never bothered with! The Black Skins! I want to know . . . how come?! Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern!” With stooped shoulders and his head hung low, the ring-slinger responds with a feeble, “I . . . can’t.”10

Although the elderly black man is drawn as a decrepit and unappealing figure and expresses his concerns in an unconvincing black dialect, the exchange between the two is profoundly engaging. Their conversation forever changed the boundaries of the superhero genre. Superheroes were no longer constrained to fighting imaginary creatures, intergalactic aliens, or Nazis from a distant past. Now they would grapple with some of the most toxic real-world social issues that America had to offer. In their respective civilian identities as Hal Jordan and Oliver Queen, the two superheroes take off in a truck together and hopscotch their way across the country to experience the real America and find their true place and purpose in it. With their existential quest interrupted by personal dilemmas that are proxies for real social issues, the series reads like a superhero version of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road (1957). By shifting the focus from villainous spectacle to real social problems plaguing the nation, Green Lantern and Green Arrow were transformed from a pair of mediocre superheroes to robust symbols of the political tensions of the time. In this sense, both characters were ideological foils for the other, infusing their comic book dialogue with real-world resonance. Interestingly, racism was a central part of the plots of the Green Lantern and Green Arrow series, and was a source of superhero reflection.

For example, in a subsequent panel from “No Evil Shall Escape My Sight,” Green Arrow underscores the immorality of racism by invoking the political assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bobby Kennedy. This point is clearly expressed by a poignant image of Green Arrow standing in the foreground of outlined images of Dr. King and Bobby Kennedy. The picture is underscored by a caption that states, “On the streets of Memphis a good black man died . . . and in Los Angeles, a good white man fell. Something is wrong! Something is killing us all! Some hideous moral cancer is rotting our very souls!”11 In retrospect, it is easy to look at such writing as maudlin and crudely didactic. Arguably, however, because Green Lantern and Green Arrow were addressing such immense social issues, both characters required grand language and imagery to match the sweeping cultural fallout and the emotional trauma the American psyche suffered from witnessing a spate of political assassinations on American soil. Green Arrow and Green Lantern functioned as elegant cultural ciphers that openly questioned the crisis of meaning and identity that Green Arrow expresses in his lament over the assassinations. Despite the ham-fisted dialogue, the Green Lantern Co-Starring Green Arrow comic book series was symbolically sophisticated when confronting white privilege and racial injustice in America.

For instance, in another issue titled “A Kind of Loving, a Way ...