- 285 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

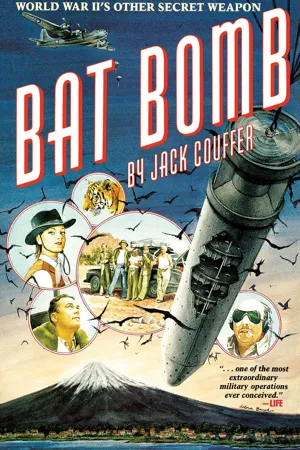

"Inside information on a wondrously droll, highly classified yarn from WWII . . . A well-told, stranger-than-fiction tale that could make a terrific movie." —

Kirkus Reviews

The plan: attach small incendiary bombs to millions of bats and release them over Japan's major cities. As the bats went to roost, a million fires would flare up in remote crannies of the wood and paper buildings common throughout Japan. When their cities were reduced to ashes, the Japanese would surely capitulate . . .

Told here by the youngest member of the team, this is the story of the bat bomb project, or Project X-Ray, as it was officially known. In scenes worthy of a Capra or Hawks comedy, Jack Couffer recounts the unorthodox experiments carried out in the secrecy of Bandera, Texas, Carlsbad, New Mexico, and El Centro, California, in 1942-1943 by "Doc" Adams' private army. This oddball cast of characters included an eccentric inventor, a distinguished Harvard scientist, a biologist with a chip on his shoulder, a movie star, a Texas guano collector, a crusty Marine Corps colonel, a Maine lobster fisherman, an ex-mobster, and a tiger.

The bat bomb researchers risked life and limb to explore uncharted bat caves and "recruit" thousands of bats to serve their country, certain that they could end the war with Japan. And they might have—in their first airborne test, the bat bombers burned an entire brand-new military airfield to the ground.

For everyone who relishes true tales of action and adventure, Bat Bomb is a must-read. Bat enthusiasts will also discover the beginnings of the scientific study of bats.

The plan: attach small incendiary bombs to millions of bats and release them over Japan's major cities. As the bats went to roost, a million fires would flare up in remote crannies of the wood and paper buildings common throughout Japan. When their cities were reduced to ashes, the Japanese would surely capitulate . . .

Told here by the youngest member of the team, this is the story of the bat bomb project, or Project X-Ray, as it was officially known. In scenes worthy of a Capra or Hawks comedy, Jack Couffer recounts the unorthodox experiments carried out in the secrecy of Bandera, Texas, Carlsbad, New Mexico, and El Centro, California, in 1942-1943 by "Doc" Adams' private army. This oddball cast of characters included an eccentric inventor, a distinguished Harvard scientist, a biologist with a chip on his shoulder, a movie star, a Texas guano collector, a crusty Marine Corps colonel, a Maine lobster fisherman, an ex-mobster, and a tiger.

The bat bomb researchers risked life and limb to explore uncharted bat caves and "recruit" thousands of bats to serve their country, certain that they could end the war with Japan. And they might have—in their first airborne test, the bat bombers burned an entire brand-new military airfield to the ground.

For everyone who relishes true tales of action and adventure, Bat Bomb is a must-read. Bat enthusiasts will also discover the beginnings of the scientific study of bats.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bat Bomb by Jack Couffer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Seconde Guerre mondiale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

This Man Is Not a Nut

FOG CLUNG to the hills, wet with winter grass; vague shapes plowed through the mist. They could have been Pleistocene beasts, like the dwarf elephant whose bones I was assisting the senior field collector to excavate, but the shadows were only cattle. We worked on the sheer side of a clay-banked gully where the remains had lain for half a million years. The ivory tusk-tip had been exposed by the last rain, and with pick, trowel, and brush we slowly brought the entire skull to light. In a plaster jacket it would go into the research collection of the Los Angeles County Museum, where I was a part-time student assistant.

We had been camped for a week near the end of Santa Rosa Island off the coast of Santa Barbara, twenty miles from ranch headquarters and the nearest people, or so we thought. Then the shapes of two riders materialized from the fog. They stopped at the arroyo edge above us, classic cowboys, with Mexican chaps and wide-brimmed hats dripping with fog.

“They told us to fetch you back to the ranch,” the elder cowboy said. “We got horses at your camp.”

“But I’ve just finished my survey and we’ve started to work,” my boss said. “We’ve got another ten days.”

“No, you ain’t.” The cowboy puffed his Camel (this was in a time before cowboys all smoked Marlboros) and swung one leg over his pony’s neck, perching high with his boot in his lap. “The foreman said bring you back, so I gotta bring you back, jque not”

“What’s it all about?” my boss asked.

“¿Quién sabe? Maybe something to do with Pearl Harbor’s been bombed?”

The offhand slouch, the cowpoke’s long drag on his cigarillo, conscious mannerisms of nonchalance, contrasted effectively with this seemingly important information.

“Where’s Pearl Harbor?” I asked.

In those first confused days of the war it was expected that the Japanese would follow up their success in Hawaii with attacks on the U.S. mainland. West coast harbors were closed with antisubmarine nets and all boat traffic was stopped. Our museum field party of seven scientists and helpers was stuck on the island. In my adolescent innocence I thought our situation was exciting, and the drama of being marooned and a week late in getting back to high school after the Christmas break made me the first one in my class with an honest-to-God war story.

I spent mornings in the structured classes of Glendale High School, afternoons as a student assistant in the labs at the museum, where I assisted the various biology curators and was now learning to collect, prepare, and catalog small mammals for the research collections in the Department of Mammalogy. My mentor in this, my favorite niche, was Jack C. von Bloeker, Jr., an authority on the order Chiroptera—bats. His enthusiasm for these flying mammals, so profoundly associated with spooks, ghosts, witches, evil, and all sorts of weird happenings of mysterious and supernatural kinds, was dangerously contagious. All of this dramatic symbolism associated with bats was romantically fetching. I soon became seriously infected with von Bloeker’s disease.

Our collecting forays took us scuffing through the musty belfries of old churches. With flashlights poking under highway bridges in Los Angeles we searched out colonies of Myotis, and from abandoned mine shafts and rock cracks in the nearby desert we collected specimens of the sixty-five or so species and subspecies of bats then known in North America. One kind, the spotted bat, rarest of modern mammals, and to my bat-besotted mind the most beautiful of creatures, was known to science from only four specimens. All had been encountered as the result of some freakish accident, as if occult forces had caused the demise—one had drowned itself in a railway water tank, another had impaled its skull on the wicked spine of a barbed wire fence. I yearned to discover the hidden secrets of this extraordinary animal—where and how did it live? Why had so few been found over so wide a diversity of habitats?

My tutor in this compulsive study of flying animals was thirty-three when I was seventeen, and he treated me and my fellow student assistant, Harry Fletcher (who was as fascinated with fossils as I was with bats), with all the understanding and perhaps more worldly insights than if we were his own sons. V. B.’s son was only three, and his two daughters at the ages of eight and four seemed disappointingly disinclined to follow his passion for natural history. One girl had a pet white rat which she clothed in dresses and hats and thus showed some promise at an early age, but her interest soon turned more to the haberdashery than to the rodent.

Von Bloeker was comfortable in the laboratory, where most of a museum curator’s time is spent, but he wouldn’t have been happy there without the knowledge that working up the data and collections from one fieldtrip would lead to another. His true calling was in the field—v. B. was essentially a collector, one of that old-fashioned breed of naturalists to whom a new specimen of any category, so long as it came from the earth or was one of its living inhabitants, was a treasure. In this respect, I thought of him as a modern-day Charles Darwin.

Von Bloeker was a chain smoker. When I press myself to recall a picture of him, I see his fine-featured face—thin, pointed nose cocked away and brown eyes squinted nearly shut—trying to see through the bluish column curling up from the cigarette forever dangling from his lips. The index and middle fingers of his right hand were stained a sickly yellow-brown, and his clothes reeked with the pungent odor of tobacco.

Fletcher was a couple of years older than me. His most noticeable personal trait was the habit of regularly combing back his straight, sandy-colored hair. Fletch wore his locks in the style known as a ducktail, a coiffure in favor with the notorious zoot suiters, but that was his only connection with that curious cult of the times.

Fletch’s hair-grooming habit was so deeply ingrained that he reached in his hip pocket every thirty minutes, brought forth his comb, and performed the customary four strokes whether his head needed it or not. This formalized routine, as unvarying and rote as blinking, was as much a part of Fletch as his pinkish complexion, an eternal blush that glowed like the tinted paraffin faces in a wax museum.

One evening after the long ride from the museum by trolley and hitchhike (in 1942, a boy could stand on the roadside with his thumb out and people would stop their cars to give him a lift, a practice now unfortunately considered dangerous for both driver and passenger), I arrived home to find an official letter headed “Greetings,” the curiously euphemistic caption for this momentous correspondence from draft boards across the nation—my Notice of Induction.

This letter, coming as it did only a few weeks before my high school graduation and coupled with my fascination for bats, doubled my interest in the unexpected visitor who blew into the stuffy Laboratory of Mammalogy like a breath of fresh air. He looked like Santa Claus without a beard, cherubic and ruddy-faced, small and plump—his white hair stood out in wild disarray, and small, round piggy blue eyes never seemed to blink, but sparkled mischievously. It was not the guru of Yule: he announced that his name was Dr. Lytle S. Adams, that he represented “the War Department,” and that everything he said, including even the fact of his visit, was a military secret.

Von Bloeker introduced me as his assistant and our visitor said, “Yes, I know about him.”

Knew about me? A seventeen-year-old high school kid? The War Department was aware of my existence? Even before I knew him I felt a warm flush of good fellowship toward this jolly-looking little man. Later I would learn that I had merely been subjected to Doc’s inimitable style. He had known nothing about me, of course, but merely reacted to the introduction in his usual disarming way, tossing off the winning allusion at the auspicious moment.

Adams untied a frayed rope from around a worn-out leather briefcase and dove into the interior, stuffed to bulging with dogeared papers. He pulled forth a document and flashed its red stamped notice with the word “Secret” conspicuously emblazoned in the margin. “Can’t let you read this,” he mumbled, implying far more textual content than there was, “but it’s my letter of authority from the Great Man himself.”

In addition to the bold security classification he allowed a glimpse of the letterhead. We saw “The White House, Washington, D.C.,” a gold seal, and the signature: Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Now, years later, in quest of the research to joggle my memory and fill in the blanks for this reminiscence, I was supplied with a copy of a letter by the FDR Library. It is a reply to Dr. Adams’s original proposal to the president and is the only personal correspondence on file from FDR in reference to our subject, so it must be the paper Doc flashed for our cursory inspection that day. The message was surprisingly cryptic in view of its import.

MEMORANDUM FOR COLONEL WM. J. DONOVAN,

U.S. GOVERNMENT, COORDINATOR OF INFORMATION.

This man is not a nut. It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into. You might reply for me to Dr. Adams’ letter.

FDR

The note was not only brief in words, it was short on character perception as well. Doc Adams definitely was a nut, but to give the old man his due, not in the dismissive context implied by President Roosevelt.

The correspondence that produced FDR’s brief assessment of Lytle S. Adams and his idea was handed to the president by his wife, for Doc had a large circle of acquaintances in the higher echelons of society and government, among them, Senator Jennings Randolph, who had introduced him to Eleanor.

Adams was a practicing dentist and oral surgeon who dabbled seriously in inventions. He had learned to fly with Glenn Curtiss in the early days of aviation, and his most successful invention was a rural air mail pickup system that made it unnecessary for the pickup plane to touch down, thus obviating landing fields in remote areas. He had demonstrated the device by delivering and picking up mail off the deck of the Leviathan in the English Channel in 1929, and regular deliveries and pickups were made from the middle of the lagoon at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1934. He sold a partnership in the system to Richard du Pont, who established pickup routes in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Delaware, and Ohio. Tri-State Aviation, of which Adams was president, was the parent company of today’s USAir.

The First Lady was interested in Adams’s invention, and he had flown her around in his own plane to different presentations. She made it possible for Adams to get the president’s ear and offer his idea for helping to win the war.

The colorful language which Adams used in his letter to the president was not typical of his writing style. It may have been Doc’s attempt to set his missive apart, to draw attention to it. If that was the case, the device was not only effective but quite within the tactical precepts of his showmanship.

My Dear Mr. President:

I attach hereto a proposal designed to frighten, demoralize, and excite the prejudices of the people of the Japanese Empire.

As fantastic as you may regard the idea, I am convinced it will work and I earnestly request that it receive the utmost careful consideration, lest our busy leaders overlook a practical, inexpensive, and effective plan to the disadvantage of our armed forces and to the sorrow of the mothers of America. It is one that might easily be used against us if the secret is not carefully guarded.

I urge you to appoint a committee to study thoroughly and promptly all the possibilities of this plan and that its members shall consist of civilians eminently qualified to not only pass upon, but solve all technical matters and recommend methods for the execution of the raids.

Dr. Adams’s letter went on to nominate a number of well-known scholars and businessmen to head the various departments that would be involved. Then he attached the following description of his scheme:

Proposal for surprise attack

“REMEMBER PEARL HARBOR”

“REMEMBER PEARL HARBOR”

Shall the sun set quickly over “the land of the rising sun”? I would return the call of the Japanese at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, with a dawn visit at a convenient time in an appropriate way. . . .

The . . . lowest form of animal life is the BAT, associated in history with the underworld and regions of darkness and evil. Until now reasons for its creation have remained unexplained.

As I vision it the millions of bats that have for ages inhabited our belfries, tunnels and caverns were placed there by God to await this hour to play their part in the scheme of free human existence, and to frustrate any attempt of those who dare desecrate our way of life.

This lowly creature, the bat, is capable of carrying in flight a sufficient quantity of incendiary material to ignite a fire.

The letter makes the point that if millions of bats carrying small firebombs were released an hour before daybreak over a Japanese industrial city they would fly down to roost in factories, attics, munition dumps, lumber piles, power plants—all the structures of a community—and the hundreds of thousands of fires ignited simultaneously in inaccessible places would be impossible to control. His letter continues:

The effect of the destruction from such a mysterious source would be a shock to the morale of the Japanese people as no amount of [ordinary] bombing could accomplish. … It would render the Japanese people homeless and their industries useless, yet the innocent could escape with their lives. . . .

If the use of bats in this all-out war can rid us of the Japanese pests, we will, as the Mormons did for the gull at Salt Lake City, erect a monument to their everlasting memory.

Adams’s letter goes on to point out that bats hibernate during winter and in this state of lethargy could be easily collected, fitted with tiny incendiaries, and transported without feeding or care other than to maintain the conditions necessary for hibernation. Just prior to release the bats could be made active again by warming.

An important consideration is that a bat weighs less than one-half ounce, or about 3 5 to the pound, which means that approximately 200,000 bats could be transported in one four-motored stratoliner type airplane, and still allow one-half the payload capacity to permit free air circulation and increased gasoline load. Ten such planes would carry 2,000,000 fire starters.

In submitting this proposal it is with a fervent prayer that the plan will effectively be used to the everlasting benefit of mankind.

Yours humbly,

Lytle S. Adams

It was essentially this incredible scheme, which already had tentative government approval, that Adams proposed to von Bloeker that day in the museum lab. In retrospect, one thing seems nearly as extraordinary as the concept of the plan itself. At no time, either in our preliminary discussions or later on as the project developed, did anyone challenge the idea from an ecological or moralistic point of view. No one addressed the issue “What about the bats?” In this day of animal rights activism and the conservation ethic such a project could probably not even be considered.

Doc’s plan involved cremating millions of animals. Each bat was to be a living firebomb: when the incendiary was ignited, the bat that carried it would go up in smoke along with the structure it was meant to destroy. Even von Bloeker and myself—confirmed bat lovers, a seasoned biological ecologist and his idealistic pupil—did not raise our voices in protest at the projected slaughter of wildlife.

Why not?

To define the answer one must look at the proposal in the context of the times. To anyone who did not experience those days of hatred and all-out effort, the mass mind-set of Americans during the war must seem incomprehensible. The dedication of humans on both sides of the struggle created a peculiar psychology unknown in times of peace or even of uncommitted war. Hysteria was fed by the press, by radio, by film and official propaganda. Few Americans would have argued in those times about the truth of Doc Adams’s statement in his letter to President Roosevelt: “The slimiest most contemptible creature in all the world is the Japanese military gangster.”

My mother, sending off a young marine friend to the war, said, “Bring me back a Nip’s ears.” She was speaking figuratively, of course, but this was a reflection of the widespread hatred of the time. The Japanese had made the surprise dawn attack on Hawaii which temporarily extinguished the U.S. Pacific fleet. Six Japanese aircraft carriers put forth 370 planes that sank four, and severely damaged two more, U.S. battleships at anchor. Hundreds of U.S. sailors and civilians were killed. The sneaky way the Japanese opened the Pacific war did much to characterize the enemy in the minds of Americans, and it bound our otherwise diverse citizenry into a single body with the same strong resolve. The “Japs” were the despised enemy, guilty of the most heinous atrocities. To many Americans of the time the Japanese were a breed apart from the rest of humanity, easily mind-warped due to their strange Asian customs, exalting in the execution of incredible acts of barbarism, torture, and rape, even to the self-immolating horror of kamikaze pilots who deliberately blew themselves to kingdom come and eternal glory by diving their bomb-laden planes into the sides of American warships.

The people of the United States were committed to winning this war they had not asked for. Few held back. Sons and husbands and fathers were dying; hundreds of thousands of young men were fighting under the most awful conditions, and women in uniform served close to the front in many ways. Women toiled at home in the defense factories which ran day and night churning out ships, planes, munitions, an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 This Man Is Not a Nut

- 2 Secrecy Is Obviously Essential

- 3 The Suggestion Is Returned as Impractical

- 4 The Army Air Forces Will Cooperate

- 5 Flamethrower

- 6 No Questions Will Be Tolerated

- 7 They Can Fly!

- 8 Chemical Warfare Concludes

- 9 The Bat-Shit Man

- 10 Ozro

- 11 Osaka Bay

- 12 Muroc

- 13 Carlsbad

- 14 Bandera

- 15 Project X-Ray

- 16 The Other War

- 17 The Hibernation Equation

- 18 The Fistfight

- 19 Dugway

- 20 It's a Bit "Sticky" in El Centro

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

- Footnotes