![]()

PART I

Expansive Christianity

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Steady Habits Upended

REVEREND JAMES COGSWELL adjusted his powdered wig then straightened the twin white preaching bands that hung from his clerical collar over the front of his black suit. A glance in a looking glass would have shown his alert brown eyes and ruddy cheeks in a clean-shaven face. He was sixty-two years of age and in good health, praise God. But the upcoming memorial service made him uneasy. A young man, full of promise, had hanged himself. The dreadful event had shaken Cogswell. “My mind feels anxious what to say with propriety on such an uncommon Occasion,” he wrote in his diary in April 1782. He hoped to find the right words, especially for the village youth gathered to commemorate their lost friend. Their conduct of late troubled him greatly. As the war for independence dragged on, bringing scarcity, inflation, and the grim news of compatriots wounded or killed, the young people in Connecticut’s sparsely populated eastern hill country exhibited strangely frivolous, even callous, behavior. Cogswell had observed “unseasonable” wartime “gaity,” also cursing, intemperance, and “merriment and revelling,” together with an “absence of seriousness” and a kind of “criminality of insensibility.” Had wickedness and then remorse contributed to the young man’s premature death? The minister planned an urgent appeal to the youth of Scotland village. Their eternal souls were in imminent danger, he would warn them. They must acknowledge their depravity, repent their sins, and seek the healing balm of divine mercy. Yet Cogswell fretted that he had not found the right tone for this sensitive occasion.1

We can imagine seventeen-year-old Elihu Palmer sitting in the Congregational meetinghouse as Cogswell arranged his notes and prepared to deliver the funeral oration. In this town of a few hundred people, Palmer would have known the young man, close to him in age, whose life had ended in tragedy. The village youth had built a pew for themselves in the new clapboard-sided church; maybe Palmer joined them on the bench. He and his seven siblings had been baptized in the old meetinghouse, which was no longer in use. His mother, Lois, before her untimely death, had for years participated in the holy sacrament of communion, and his father, Elihu Palmer Sr., served for many years as a member of the ecclesiastical society that oversaw church governance in Scotland Parish. For over a decade now, Cogswell had preached the Sunday sermons. Palmer was probably even then studying with Cogswell, whose ministerial duties included religious education for the youth in town, along with preparing eligible young men for college.2

Two momentous upheavals shaped the society in which Palmer came of age: the Protestant religious revivals, later dubbed the First Great Awakening, that had begun when his parents and Reverend Cogswell were young themselves; and the American Revolution, which had been waged during Palmer’s youth. Both events raised questions of lasting import: Which sources of moral and political authority were legitimate and trustworthy? What was the proper mix of reason and emotion in religious faith and political fealty? Which forms of religious devotion most pleased God and encouraged moral conduct? These questions were not merely academic, as those who gathered for the memorial service understood. The answers either helped or hindered as one tried to find moral ballast in turbulent times. In Cogswell’s view, only a rational and earnest faith could ward off the most dangerous impulses, be they religious or political. As he prepared the funeral oration, he could look back on decades of religious tumult and try to distill life’s lessons in ways that might persuade and protect the youth of Scotland village.

Since Elihu Palmer wrote nothing about his family or his childhood and no personal papers from his parents have survived, Cogswell’s diary offers a singular glimpse into the world of Palmer’s youth. Cogswell’s ideas about religion and politics must have influenced this churchgoing boy, who would study for the ministry and ever after concern himself with theology. Elihu Palmer came of age knowing that his parents and minister chose traditional church authority over emotionally charged religious revivalism. From Cogswell the boy would have heard about the dangers of piety gone awry, the hazards of relinquishing one’s reasoning powers to an emotional experience of the Holy, and the importance of keeping one’s critical faculties intact when others seemed to be losing their wits. Immorality could come under the guise of a holy possession, as Cogswell knew firsthand. Palmer was probably raised on tales of the revivals that flamed up before he was born, searing souls and scorching friendships and family ties. The outlandish behavior of the born-again made for shocking stories that conveyed just how thin the barrier of reason was when religious emotions took hold. The adults closest to young Palmer held convictions of faith forged in an era of religious turmoil and stark choices. For them, the crucial role for reason in religion was no abstraction; it was an urgent lesson they passed on to the bright, young boy.

Cogswell remembered well how the religious revivals began. In October 1740, when he was twenty, news spread by word of mouth that the traveling English minister, George Whitefield, was preaching in Middletown, Connecticut. People left their farming tools in the field and their tasks unfinished and rushed to hear the charismatic speaker. Whitefield’s vivid, emotive, and extemporaneous preaching, which was marked by dramatic gestures and strong feeling, gripped his audiences. He reminded those gathered that all humans are born into a state of moral depravity. Sinners cannot save themselves from the punishment they so richly deserve, he said, and an “Eternity of Misery awaits the Wicked in a future state.” One’s only recourse was to repent and humbly pray that the Holy Spirit will “reinstamp the Divine Image upon our Hearts, and make us capable of living with and enjoying God.” As the crowd witnessed Whitefield’s impassioned exhortations, some felt the inner working of a saving grace. One Connecticut farmer said that hearing Whitefield preach “gave me a heart wound.” It was an emotional devastation of the best kind, people later said, with the power to change their lives.3

Not everyone appreciated Whitefield’s message or method. A physician in Middletown reported to a friend that the “Famous Enthusiast Mr. Whitefield was along here, making a great Stir and noise.” Doctor Osborn disparaged Whitefield’s extemporaneous and emotional preaching style as a “heap of confusion, Railing, Bombast, Fawning, and Nonsense” marked by “distorted motions, Grimaces, and Squeeking voices.” The emotional appeal was precisely the problem, Osborn thought. For without one’s reasoning faculties in play, how was one to know that it was the voice of God in one’s head and not satanic delusion?4

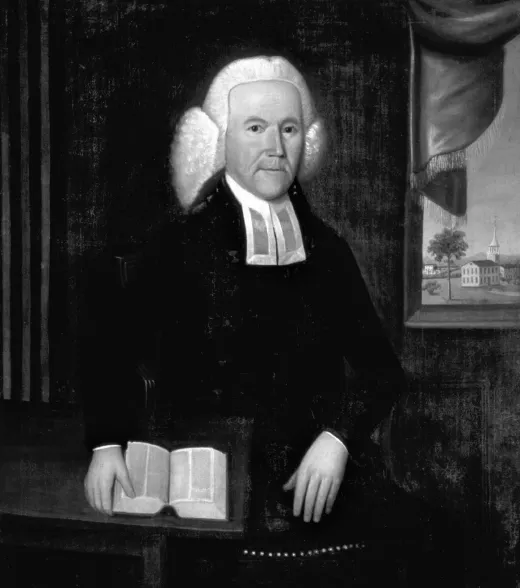

FIGURE 1. A portrait of Reverend James Cogswell, ca. 1795–1799. Reverend Cogswell served as a minister in Scotland, Connecticut, from the time Elihu Palmer was seven until he left home for college. Cogswell’s piety and sociability shaped how Palmer viewed a career in ministry. Courtesy of Historic New England. Gift of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little, 1991.1445.

What, indeed, constituted authentic religious experience? Did it suffice to use finite human reason to study the revealed word of God in the Bible? Or did direct, emotional experiences of the Holy Spirit more reliably convey a sense of God? Did reasoned exegesis from a theologically trained minister best convey God’s will, or the powerful experience of the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit? These pressing questions continued to preoccupy people well after Whitefield had moved on.5

In eastern Connecticut, as elsewhere, local preachers took up the new form of preaching, referring to a few notes rather than reading aloud their sermons. As the delivery became more direct, the message gained in emotional impact. Twelve miles west of Scotland in Lebanon Crank parish, Reverend Eleazar Wheelock exhorted his congregants about the utter depravity of humankind and the need for the redemptive power of being born again in Jesus Christ. Wheelock counted himself among the New Lights, and within a year, nearly three hundred members of his own “dear flock” had also been born again. Wheelock and other New Light preachers especially targeted church members in good standing, the pious folk who regularly attended church service, took part in the Lord’s Supper, and did their best to follow the example of Christ. None of this was any good, New Light revivalists warned, unless one felt overcome by the Holy Spirit. Without the transformative experience of being “regenerated,” or born again, all Christian rituals were worse than useless; they obscured a sinner’s depravity and encouraged a smug pride that ended in everlasting damnation. Even upstanding members of the church were not true Christians unless they had experienced the living spirit of Jesus. The same was true of ministers who had not experienced a saving grace powerful enough to take their breath away. Outward piety and knowledge of the Scriptures were nothing. Love of God must be written directly on the heart.6

Other ministers displayed more physical manifestations of the divine power at work. Wheelock’s brother-in-law, James Davenport, was an ordained Congregational minister when he encountered George Whitefield and the Irish Presbyterian revivalist Gilbert Tennent. On fire for God, Davenport took to the road and preached to large audiences, often outdoors and without the consent of local ministers. His speeches came to him as immediate revelations of the Holy Spirit and lasted for hours on end. He repeated words and phrases as a chant or a shout, riffed on excerpts from the Bible, and offered graphic accounts of torments in hell. At his meetings, Davenport encouraged his listeners to engage in extemporaneous prayer and exhortation, resulting in a cacophony of sound: singing, laughing, shrieking, and weeping. His gift of spiritual discernment showed him who among the settled ministers was saved and who was the “Devil incarnate.” When he ordered a public book burning in New London in 1743, a hundred men and women threw their volumes into the flames, especially the “heretical” ones penned by ordained but unregenerate ministers.7

As the revivals took hold in eastern Connecticut, familiar hierarchies frayed. People with no theological training and marginal social status spoke with new authority in matters of the spirit. Native American converts arrived to preach and sing with the congregants in Lebanon. A black man sermonized at an outdoor meeting of the Colchester congregation, eighteen miles from Scotland. In Canterbury, an enslaved man named Pompey stood up during a meeting and exhorted his owner’s son in the matter of conversion. Women described extraordinary religious experiences and men believed them. Children fell into trances and revived after days of stupor to tell astonished adults about their visions. In these unsettled times, spiritual authority shifted in new ways, inverting the customary relations of respect. For many, it was a moment of much promise when spiritual power could, at least for a while, override social norms.8

All of this the Palmers and their neighbors in Scotland village heard about with amazement, while the ministers they knew best, Reverend Ebenezer Devotion in Scotland and Reverend James Cogswell, who was then still in the neighboring town of Canterbury, became personally entangled in the struggle. As Old Light ministers, who required that church members display upright behavior rather than evidence of a personal experience of divine grace, Devotion and Cogswell could hardly avoid sparring with the revivalists. Connecticut had an established Congregational church, which meant its governing structure was codified in a law (the Saybrook Platform) passed by the colonial legislature in 1708. The church could draw on civil power to enforce ecclesiastical rules. Dissenters who defied official church injunctions about who could preach or take communion could be fined or jailed by state authorities. Called Separates or Separatists because they wished to leave existing congregations to create independent ones, the dissenters objected that legal might did not make moral right. They resented the compulsory church taxes that paid the salaries of settled ministers. They also thought that ministers should be chosen by the individual congregations, not by a regional association of clergy. Their independence from the law stemmed, revivalists said, from having covenanted directly with God, while the settled ministers and their congregations had merely come together under “the Saybrook Platform, which we think to be disagreeable to the word of GOD, and therefore reject it.” The Separates harkened to a power above the law of mortals.9

When Cogswell arrived in Canterbury in 1744, he was a twenty-four-year-old graduate from Yale College, an institution founded for the purpose of educating Congregational ministers. Cogswell had not been born again and did not require that would-be church members testify to a personal conversion experience. Canterbury had been without a minister for three years, during which time laypeople preached to the congregation. Two of these, Elisha and Solomon Paine, were well-connected townsmen who had converted during the revivals. Soon after Cogswell’s arrival, Elisha Paine, a lawyer, approached Cogswell after a lecture and said “with a grave Countenance” in a room full of people that he would rather be “burnt at the Stake than to have heard such a Sermon.” The whole thing had been “Trifling,” he complained, an exercise in proving something obvious, “like a young Attorney at the Bar.” Paine also objected to Cogswell’s claim that “we must have recourse only to the Word of GOD, to prove that CHRIST suffered and died for Sinners.” In Paine’s view, conversion to faith in Jesus the Redeemer could come about in other ways too, not only through reading the Bible but also and more powerfully through the direct “Influences of the Spirit of God” on an individual.10

Paine and Cogswell conversed at length. They discussed whether any sin is unforgiveable, whether all souls will eventually be saved (Paine thought not), and what constitutes a saving faith. To the last point, Paine said God had disclosed that “CHRIST died for me.” What could be clearer evidence of his salvation than this direct message? Cogswell argued against that certainty in favor of a hopeful faith absent any divine confirmation. Paine remained firm in his conviction, claiming that “the old Puritan doctrine” of an immediate and personal conversion experience was “much safer to hold” than the notion “that a Person might be Converted, and not know it.” Both men brandished their arguments, and Cogswell’s recounting of the exchange suggests he enjoyed the theological discussion in a room full of witnesses. He took seriously his duty to instruct in matters of theology, and he gladly parried the revivalist message that theological training was of no consequence if one had personal experience of the Holy Spirit.11

The revivalists remained unmoved, however, and Paine persisted in his opposition to Cogswell. He defied the General Assembly’s prohibition of unauthorized itinerant preachers and became a lay preacher himself in the raucous style of James Davenport. The revivalist tumult in Canterbury grew so heated that it made news elsewhere. The Boston Gazette reported in December that “Canterbury is in worse confusion than ever.” Without a settled minister, “they grow more noisy and boisterous so that they can get no minister to preach to them yet.” Lawyer Paine “has set up for a preacher,” the Gazette continued, and he goes “from house to house and town to town to gain proselytes to the new religion. Consequences are much to be feared.”12

Throughout that year and into the next, tensions in Canterbury flared over who had the authority to choose the town’s new minister. A minority in town supported Cogswell, while the revivalist faction refused to hear him and met illegally in private homes, risking the consequences. Elisha Paine spent a month in the Windham County jail for his unauthorized sermons, preaching from his prison cell in the “Spirit of the Lord.” When Cogswell was installed as pastor, the revivalists refused to acknowledge both his ordination and the authorities behind it. They soon found themselves out of doors and effectively without a church at all. Undaunted, these fifty-seven townspeople, many from wealthy families and related to one another, formed the Canterbury Separate Church, with Solomon Paine as its minister.13

As Cogswell settled into his position as Canterbury’s minister, the revivals continued to challenge traditional norms. One of the most troubling manifestations of this spiritual revolution was the idea of perfectionism. Some converts believed the experience of salvation through divine grace meant they could commit no sin, even when they aggressively flouted entrenched norms. In 1748, just two years after Reverend Devotion banished Mary Wilkinson from the Sco...