![]()

Chapter 1

The Eternal Hunt for Glory

Pompey’s settlements in the new province of Pontus and the function they were intended to fulfill need to be seen in the context of the overall organization after the Third Mithridatic War. The rearrangement of Anatolia and the Near East from the Caucasus in the north to the Red Sea in the south widened Rome’s sphere of interest to the borders of Egypt, Arabia, and the Parthian kingdom. It was a considerable military and administrative achievement, which is best described as a project that developed gradually as Pompey’s campaign moved along. It is difficult to say exactly what kind of plan Pompey had for the East when he replaced Lucullus in the war against Mithridates and Tigranes, but there are elements to suggest that they grew more ambitious as he proceeded, particularly when he realized that the war against Mithridates and Tigranes would not last for long. What he set out to do and how he planned to organize the region afterward therefore need not have been what he ended up doing and may have developed as new opportunities presented themselves. In other words, the thorough reorganization of the East, including the foundation of three provinces and the ambitious urbanization of the Pontic hinterland, would not necessarily have been on the table when the campaign against the pirates brought him into Asia Minor.

The desire for prestigious commands was an essential feature throughout Pompey’s public life, as it was for any Roman politician with the resources to pursue large-scale military and political ambitions. What made Pompey stand out from most other ambitious men in Roman politics was not the desire to surpass his peers but the lengths to which he was prepared to go to in order to fulfill his goals and, equally important, what seems to be a strong desire for recognition both militarily and politically. This ambition for both prestigious victories and influence on Roman politics was always a central element in Pompey’s public life but seems to have reached a peak in the years after his consulship in 70 BCE when he, with the help of the tribunes and considerable popular support, acquired extraordinary financial and military resources to fight first the pirates in the Mediterranean and later the war against Mithridates and Tigranes.

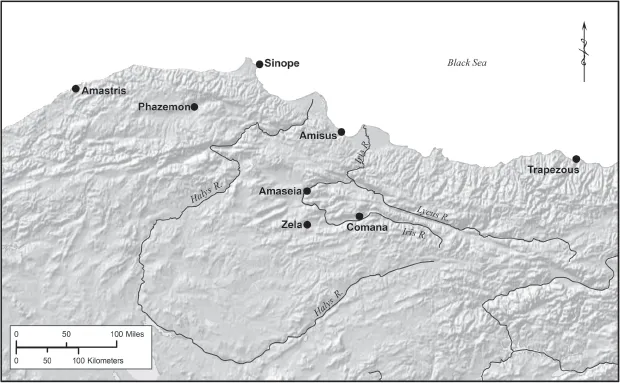

Other Roman generals, such as Scipio, Marius, and Lucullus, had previously been given extraordinary commands of various kinds, and Marcus Antonius, the father of Mark Antony, had already as praetor been allocated significant powers to solve the problem of the pirates in 74.1 Yet the extent of the command that Aulus Gabinius, the tribune of the year 67 BCE, proposed should be given to one of the ex-consuls was without parallel in both the size of the forces and the resources allocated him. The 6,000 talents, 500 ships, 120,000 infantry, and 24 tribunes and the right to operate in an area of 50 kilometers from the coastline everywhere he needed was unprecedented (Plut. Pomp. 26).2 The proposal was not surprisingly met with considerable opposition from a rarely united Senate, which further complicated what was an already problematic relationship with Rome’s aristocratic elite. The war against the pirates brought Pompey into Asia Minor just at the time when, after a promising start, Lucullus was beginning to lose his grip on the campaign against Mithridates and Tigranes. In 67, with Lucullus absent, a part of his army led by his legates suffered a devastating defeat to Mithridates near the temple community of Zela, where, according to Plutarch, 7,000 legionaries, 150 centurions, and several military tribunes lost their lives (Plut. Luc. 35.1–2).3 The heavy casualties and the dissolution of the army forced Lucullus to withdraw, while Tigranes invaded Cappadocia and Mithridates took back control of his kingdom. From a military perspective, Pompey was the logical choice to take over from Lucullus. Not only was he winning against the pirates, he was conveniently already in the region with a considerable army and had the military authority as well as the momentum to turn Lucullus’s demoralized soldiers around—in short, he had a considerably better chance of winning the war.

Scholars generally agree that Pompey had his eyes set on the Mithridatic command before Lucullus’s troubles started to materialize in the early 60s and efforts were then made in Rome to limit the mandate Lucullus received to fight Mithridates and Tigranes. In 69 the Senate turned Cilicia into a consular province with effect from the year 68, and Asia, also in the year 68, was restored and placed under the authority of a praetor. Gabinius, one of Pompey’s devoted associates, used his powers as tribune in 67 to propose another law that narrowed Lucullus’s mandate further when the people turned Bithynia with troops over to the former consul Acilius Glabrio.4

Map 1. Roman Pontus before the urbanization by Pompey.

Lucullus’s initial progress against Mithridates and the important victory against King Tigranes at Tigranokerta in October 69 meant that part of the region now lay well behind the front line and consequently could be seen as stable enough to be governed as a regular province. It has been suggested by R. Kallet-Marx that the changes to Lucullus’s mandate need to be seen in light of the progress he made, which called for a new form of organization, not as an attempt to weaken the general’s command, but as a natural next step forward.5 Seen in isolation, Lucullus’s progress perhaps justified the changes to his powers, and it is not difficult to imagine that senators or ex-magistrates were looking to become the next governors in Asia Minor.

Kallet-Marx is therefore right to point out that the Senate did not necessarily aim at watering down Lucullus’s command. It was Marcius Rex, Lucullus’s brother-in-law, who was allotted Cilicia. He for one was in no hurry to acquire his province just as it has to be remembered that for strategic reasons Cilicia needed a governor who was present in the province, not someone who was fighting wars elsewhere. Yet it is worth remembering that the changes to Lucullus’s mandate had already been carried out before the defeat at Zela and it is indisputable that Gabinius played a key role in the attempt to narrow down Lucullus’s powers, which suggests that there were ulterior motives behind the changes to Lucullus’s imperium that do refer back to Pompey.

Cassius Dio emphasizes, as does Plutarch, that Lucullus was accused of prolonging the war intentionally and that he was believed to be waging the war not to subdue the kings but to plunder their kingdoms, a point of view readily available in Cicero’s speech in favor of Manilius’s law that would recall Lucullus and offer Pompey the command against Mithridates and Tigranes (Plut. Luc. 33.4; Cass. Dio 36.2.2). Dio seems unconcerned about whether these accusations were justified or politically motivated but goes on to describe how, with success, Lucullus moved on into the Near East and how he caused considerable damage to both kings before being recalled in 66 BCE. Yet Dio does suggest that Lucullus offered Tigranes an easy escape, focusing on how the general was plundering the region rather than on apprehending the king, which in part is a general tendency in Dio to characterize almost every Roman politician in the Late Republic as greedy and keen to maximize his own personal gains.6

In any case, the opportunity to take over the command against one of Rome’s most resourceful enemies in the first century must have been a very attractive one to Pompey, not least because a victory in the East would allow him to win back some of the support he had lost when, despite the opposition in the Senate, he initiated the campaign against the pirates. That members of the Senate were receptive to successful campaigns and prestigious victories was already clear from the support Pompey enjoyed from a number of senators as the news of his success against the pirates began to reach Rome. As suggested by Dio, what made Pompey attractive, particularly to up-and-coming senators such as Cicero and Caesar, was the public support he enjoyed, which must have increased considerably after his success against the pirates. According to Dio, by supporting Pompey they themselves hoped to benefit from the general’s increasing popularity with the public (Cass. Dio 36.43).7

Pompey’s general ambition, repeated quest for prestigious campaigns, and desire to celebrate yet another triumph were no doubt other reasons why he reached out for the campaign against Mithridates. It is also worth noticing that the Senate did not propose a change of command, nor was Pompey, as far as we know, approached by some of Rome’s magistrates asking him to replace Lucullus. Instead, he was given the campaign against Mithridates and Tigranes by the adoption of the lex Manilia, which Manilius, another of his associates, prepared and saw through the assembly. To be the general who defeated the kings had considerable potential and had been an aim for many Roman generals since Rome’s first war against Mithridates in the early 80s. Not only would a victory against an enemy that Rome had fought for more than two decades set Pompey apart from any of the previous attempts to bring down Mithridates (and later Armenia too),8 it would also allow him to return to Roman politics as the general who had subdued Anatolia and the Near East and so ensured Rome a tighter grip over a region that had previously caused considerable military problems.

Even if we do not need to see economic motives as the primary reason behind every one of Rome’s wars, exploitation of newly conquered territories was one of the main objectives behind Rome’s expansion. Taxation, together with plunder, confiscation of land, and the slave trade, was a natural outcome of warfare and was a calculated prize for the general, just as it was for his soldiers, who got their part of the spoils, for the state, and for the people of Rome, who expected their share of the success as well.9

One of the motives ascribed to the establishment of the new provincial communities and the ambitious urbanization of the Pontic hinterland has been seen as an ambition to secure more land for the publicani on which they could collect tax revenues.10 Taxation was no doubt an important element in the organization of the new provinces and Pompey had financial interests in mind when he, in moderate form, restored the Gracchan tax system in Asia, which Sulla had earlier replaced with a less radical form in 84.11

The scope of the entire rearrangement of the East, including the foundation of the new provinces and several new cities across Anatolia and the Near East, seems, however, an ambitious plan if the aim was primarily to accommodate requests for more land to tax. The project to conquer Anatolia and later reorganize the Near East not only constituted a major military and administrative task, but also carried considerable risks, which had the potential to ruin Pompey’s political life. When discussing the motives behind Pompey’s plans for the East, it must be remembered that there were less ambitious alternatives than a form of organization that involved the establishment and protection of three provinces in a region where the influence from Rome had previously been marginal. Also, a province in the former Mithridatic kingdom was not immediately attractive to the publicani, since considerable logistical and geographical challenges complicated the collection of tax in an area where it would be a new phenomenon—at least in the way it was done by the Romans.

Instead of placing the entire region under direct Roman rule, Pompey might have added the old colonies on the Black Sea littoral to the province of Bithynia and divided the hinterland among the most loyal dynasts available in central Anatolia. Zela could have continued as a temple community and together with Comana supervised the southeastern part of Mithridates’ kingdom, while a loyal client ruler in Armenia, such as Tigranes turned out to be, could have been given control over the central parts of his kingdom. Another option would have been to give Deiotarus—one of the Galatian nobles—a larger share of the Pontic heartland.

An organization based on local rulers was no alien idea, as underlined by Lucullus’s plan for the region or by the strategy Antony followed when he reorganized Pontus some thirty years later. The decision to turn the kingdom of Mithridates VI into a province should therefore be seen as a deliberate and extremely ambitious choice that placed the Roman administrative structure under considerable pressure—not least because this previously hostile region had only just been conquered and because of the general lack of urban culture in the Pontic hinterland around which a provincial administration could be organized.

The magnitude of the solution Pompey chose and the risks he took politically, should the new provinces or cities prove unsustainable, suggest that the general was driven by more than a need to repay the support from the equestrian ordo. In the rest of the chapter, his considerable ambition to exceed other Roman generals and so surpass what any Roman general had previously accomplished will be seen as what in the end drove Pompey to choose as he did. This desire for victories and glory may be explained as a result of a problematic relationship with the Senate both before and after his consulship in the year 70 BCE. In 66, Pompey could not count on a large number of friends in the Senate, even if more influential members of the consularis supported his command against the kings. However, a victory against Mithridates and a large-scale reorganization of the East would be the kind of victory that would make his reentry into Roman politics less complicated. It also would be the sort of achievement that would generate the kind of public support that could allow him to confront his critics and reassume the strong position at the center of Roman politics that he had jeopardized when acquiring the command against the pirates and Mithridates in the first place.

It is in the light of the campaign farther into the Near East, as well as the ambitious attempts to rearrange the political borders in the region, that the urbanization of the Pontic hinterland needs to be seen. The cities were pieces of a much-bigger puzzle that was to figure Pompey as conqueror of the East and one of Rome’s most renowned generals of all time. In a Pontic context, the cities were to provide the administrative backbone in a province of considerable size, not simply a way to provide new and more land for the publicani to tax. Instead, the urbanization of Roman Pontus was an important element in Pompey’s propaganda and self-promotion as the new Alexander who succeeded where every other Roman general had previously failed. It was a symptom of an aggressive form of imperialism that is particularly evident in Late Republican Rome. Here, conquest and wars against foreign enemies took on a life of their own in which members of the political elite strove to surpass each other in order to acquire the wealth, military prestige, and overall success that were becoming ever more important in the struggle to win and uphold a leading role in Roman politics. To better understand the choices Pompey made as part of the organization of his Roman Pontus, we turn to his first appearance on the public stage to see how he managed his public career and how he came across to members of Rome’s political elite.

The Desire to Be Recognized

The uneasy relationship between Pompey and the Senate goes back to his early twenties, when his public career got off to a difficult start. Pompey arrived relatively late to the political scene in Rome. The first Pompeius to reach the consulship was Quintus Po...