![]()

CHAPTER 1

Engelhard, Langheim, and the Nuns of Wechterswinkel

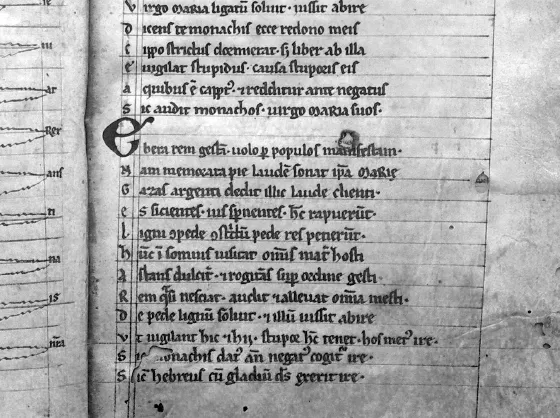

On the last folio of a text in a thirteenth-century codex from the Raczyński Library in Poznań, Poland, an acrostic poem spells out the Latin name ENGELHARDUSS (Figure 2). The poem, which sings the praises of the Virgin Mary, also appears some twenty-five folios earlier as the coda to a story in which Mary rescues a servant from brigands.1 No “Engelhardus” appears in the tale, nor does this name occur elsewhere in the manuscript. Even the authors and recipients of the letters copied into this codex are designated only by their initials.2 Another manuscript, however, spells out the full names of the correspondents, allowing modern scholars to attribute these compositions to Engelhard of Langheim.3 Whether the acrostic was Engelhard’s own poetic puzzle or that of a later scribe is not possible to determine, but the manuscript’s reticence about the author of its texts reflects Engelhard’s literary modesty and the difficulties in excavating his life from the traces left in his writings.

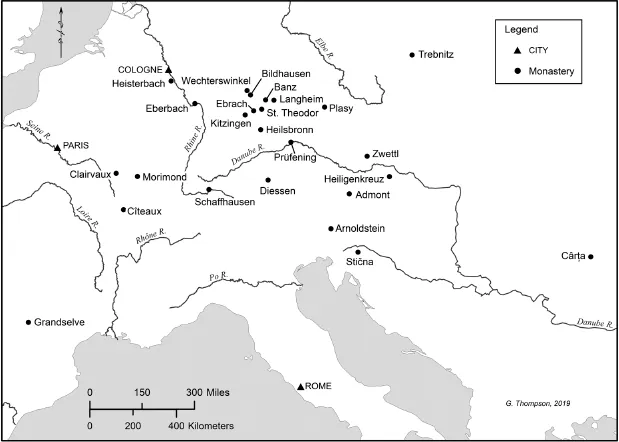

Engelhard’s writings do not purport to be autobiographical. Engelhard wrote in a distinctive voice that occasionally ventures into the first person, and his stories and letters offer glimpses of his personality and concerns, providing unusual access to the worldview of a monk intellectually and physically distant from the center of the Cistercian order (Figure 3).4 No other sources mention him, perhaps because multiple late medieval and early modern fires left few extant documents from Langheim’s libraries. The fragmentary information Engelhard did leave illuminates how his regional connections and networks influenced his interpretation of a traditional Cistercian culture and his distinctive expression of monastic spirituality.

FIGURE 2. Engelhard’s name in an acrostic poem. Poznań, Biblioteka Raczyńskich, Rkp. 156, fol. 120r.

Engelhard lived most of his life as a Cistercian monk. The daily routine of his monastery formed his character and shaped his ideas. Monastic regulations molded everything from his gestures and bearing to his clothes, his food, and his patterns of sleep, and the liturgical setting for his actions gave them a transcendent significance that influenced patterns of thought as well as behavior. Yet Engelhard also established important connections outside his monastery. Not only did he collect stories from the agricultural workers around his abbey, but he also developed friendships with monks from non-Cistercian communities, with religious women, and with a powerful family that, by the late twelfth century, controlled both ecclesiastical and secular centers of power in the region. Through these networks, Engelhard encountered other monks who also collected narrative tales and who also explored the spiritual equality of religious men and women.5 His interactions with his patrons and friends influenced his assumptions that nuns and monks formed a single sociological category described by similarly gendered characteristics, and they convinced him that women could successfully follow the customs and practices of a male Cistercian monastery. Out of his efforts to maintain the traditions of his monastic community, he articulated something new.

FIGURE 3. Engelhard of Langheim’s monastic connections.

Engelhard of Langheim

The dates of Engelhard’s birth and death are unknown.6 His correspondence with better-documented figures supply a few dates, his comments offer hints to his activities and outlook, and the manuscripts containing his compositions suggest his networks and his influence. These fragments depict a man who was curious about the world around him, who had administrative responsibilities in a well-to-do and locally prominent abbey, and whose interactions with other monks and nuns enhanced his skill in collecting and recounting stories. While lacking specific biographical details, Engelhard’s texts provide insights into the world of a late twelfth-century Franconian monk and the formation of his ideas.

Engelhard was born in Bamberg and spent most of his life about thirtyfive kilometers to the northeast, in the Cistercian monastery of Langheim. In the narration that connects his stories, Engelhard remarked that his father’s death left him an orphan and that he was raised by Volmar, a deacon in Bamberg.7 A Volmar appears in charters that bishops of Bamberg issued between 1145 and 1165; he is at times listed as “deacanus” and at times as “sacerdos.”8 If this was Engelhard’s foster parent, then it is likely Engelhard was born sometime in the 1140s or 1150s. Engelhard praised Volmar for his kindness, simplicity, and virtue and for nurturing other orphans as well. At least one of these foster brothers also became a Cistercian monk.9

Engelhard considered himself unlearned and described his education as “rustic.”10 This was more a humility trope than a statement of fact. Engelhard was clearly literate. Nonetheless, his education was not that of his scholastic contemporaries. In the eleventh and early twelfth centuries, the cathedral school in Bamberg had been an important site for educating imperial officials, and in the twelfth century, it continued to stress the importance of grammar, rhetoric, and the formation of morals even as these subjects began to seem outdated.11 Engelhard appears to have absorbed only parts of this traditional educational program. His prose is not that of a Latinist with an ear tuned to classical rhetoric, and his works contain few classical references. Nonetheless, he recognized the importance of learning virtue by modeling one’s behavior on that of one’s teacher, describing his foster brother, Bertolf, as learning from Volmar by “copying in himself the image of his nurturer.”12 At his best, Engelhard wrote with the direct and vivid language of a storyteller, weaving Biblical language and imagery into his stories and reproducing in texts the qualities of a face to face teaching that imprinted morals as well as knowledge. When he tried to impress his reader, as in some of his letters, his prose loses its vividness.

Engelhard’s sense of himself as unlearned may have stemmed from his recognition that the intellectual center of late twelfth-century Europe had shifted toward the Parisian basin and northern Italy and that training in logic, theology, and law had become important for ecclesiastical advancement. Engelhard did not attack the urban schools with the polemical language that some of his Cistercian contemporaries employed, but he nonetheless viewed these educational developments with suspicion. He contrasted himself to scholastici, he sniped at scholars who were “too busy with their laws and decretals” to write a saint’s life, and he emphasized that one could learn more from experience than from books.13 Even his description of Volmar stressed virtue over book learning. Engelhard claimed that a metricus from the school at Bamberg had said of Volmar, “from his boyhood, he was not so much a poet as a prophet.”14 When Volmar went to Paris, Engelhard thought Volmar’s holy simplicity more noteworthy than his scholastic education. As Engelhard explained, Volmar “never deigned to know what a pound was.” When he sold his horse after arriving in Paris, he refused to accept two pounds of silver, insisting instead that the buyer place “thirty pennies in this hand, and the same amount into the other.”15 The scholars admired Volmar’s purity rather than mocking his lack of sophistication, and Engelhard thought they found in him the innocence of a dove rather than the shrewdness of a serpent (Matthew 10:16). A Parisian focus on arts and dialectic had attracted this Bamberg deacon to Paris’s schools sometime in the middle of the twelfth century, but Engelhard’s story presents Volmar as retaining Bamberg’s traditional focus on moral education. Engelhard did not follow Volmar to Paris for even a brief taste of scholastic life. Instead, while probably still in his teens, he made the conscious decision to become a monk at Langheim.

Other than a brief tenure as an abbot in Austria, Engelhard remained at Langheim until his death. His first years as a monk were difficult. He described a period in his adolescence when, “conquered by tedium, unable to endure the temptation, and considering nothing other than to leave,” he hardened his heart and refused to listen to the older monks who offered him help. Eventually, the prior Otto knocked down his defensive wall and “by bringing aid to one considering flight, he roused me when I waivered, corrected me when I vacillated, and sent me back to fight again, stronger and better because of his word.”16 Although Engelhard later became an abbot and must have been a priest, he never mentioned his ordination or his performance of sacraments. He was more focused on his position as a monastic official, “caring for the business of the house.”17 As either cellarer or prior, he witnessed events that he later recounted in his stories. He was summoned when the wife of a shepherd brought a stolen eucharistic wafer to Langheim, and he was present in an unnamed monastery when the brothers found a monk naked and dead in the cellar.18

Engelhard is unusual among Cistercian authors in describing the agrarian society that surrounded his community. Two of his tales involve female weavers, one includes a shepherd, and one concerns a servant from the monastery of Ebrach. Another story originated with the local miller. Engelhard also recounted a tale he heard in the vernacular and translated into Latin.19 He noted the presence of hired workers, and he included Cistercian laybrothers as protagonists in his stories, depicting their spiritual equality with the monks.20 His interest in a nonsacerdotal religiosity extended to laybrothers as well as to Cistercian nuns.

Many of Engelhard’s stories stemmed from a Cistercian network of abbeys. Engelhard set a third of his tales at Langheim, but others depended on Langheim’s affiliation with the Cistercian order.21 When Langheim was established, around 1132, its first monks came from Ebrach, a Cistercian community positioned halfway between Würzburg and Bamberg. Monks from the Burgundian abbey of Morimond had founded Ebrach some five years earlier. Adam, Langheim’s first abbot (c. 1141–1180), probably first professed at Morimond, moved to Ebrach, and then transfered to Langheim. The abbot of Ebrach conducted yearly visits to the abbeys that Ebrach founded, the abbot of Morimond also visited the abbeys in his filiation, and the Franconian abbots traveled yearly to the meeting of the order’s Chapter General at Cîteaux. Engelhard relied on these connections for many of his stories. In one of his letters to Erbo of Prüfening, Engelhard recorded a tale he had heard at the Cistercian Chapter General, suggesting he attended the meeting at least once before 1188. At Cîteaux, he probably encountered other Cistercian monks interested in collecting stories.22 He also relied on the movement of monks between monasteries and the travels of abbots on the order’s business. The abbot of Morimond provided one of Engelhard’s tales while a monk named Bezelin brought Engelhard four stories from Cistercian houses in France. Other tales, however, came from non-Cistercian connections. A Chuno, who left Langheim for the Hirsau-affiliated abbey of Schaffhausen, returned after experiencing the horrific death of one of the Schaffhausen monks, and he recounted the tale to his Langheim brethren.23

In the 1180s, Engelhard developed an epistolary friendship with Erbo, who served as abbot of the Regensburg monastery of Prüfening between 1168 and 1187. The two men appear to have exchanged letters before they met in person, but we do not know what initiated their contact.24 Bishop Otto I of Bamberg had helped establish both Prüfening (c. 1119) and Langheim (c. 1132), but Prüfening followed the customs of Hirsau while Langheim was Cistercian. A former Regensburg schoolmaster, Idung, had left Prüfening for an unnamed Cistercian house around 1153 and composed an apologetic treatise praising the Cistercians. It is possible that his departure triggered an interest at Prüfening in Cistercian customs and practices.25 But it is more likely that Erbo, like Engelhard, wished to teach his community using stories and that their friendship centered on Engelhard’s supply of didactic tales.

The six letters that Erbo and Engelhard exchanged contain elaborate expressions of humility that frame Engelhard’s stories and Erbo’s requests for still more tales. Some concrete information emerges alongside these rhetorical flourishes. In his first letter, Engelhard asked Erbo to return his libellus because Engelhard’s abbot thought that Engelhard had shared Cistercian stories with Erbo without permission. Erbo sent back the book but also gave Engelhard more parchment so he could continue to write.26 This libellus was probably an early version of the story collection that Engelhard dedicated to the nuns of Wechterswinkel sometime after 1188. Embedded in Engelhard’s letters are five more tales. None of these five stories appear in the composition for the nuns, although in some manuscripts, two appear among the stories later appended to Engelhard’s collection.27 Instead, Engelhard added new stories and a writer’s apology to the libellus, and he sent it with a letter of dedication to the abbess and nuns of Wechterswinkel in return for an unspecified favor.

Engelhard’s tenure as abbot remains a mystery. In his correspondence with abbot Herman of Ebrac...