![]()

Chapter 1

Imperial Picaresques

La Lozana andaluza and Spanish Rome

Francisco Delicado’s Retrato de la Lozana andaluza (1528) is an extravagant text, wandering far and wide in its attempts to capture its slippery protagonist. Geographically capacious and narratively playful, Lozana tells the story of a Cordoban prostitute whose travels across the Mediterranean bring her to Rome and a community of exiled Jews and conversas. In its broad geographical sweep, Delicado’s picaresque functions as a perverse counter-epic of one, as the imperial theater of Italy offers refuge to a protagonist who must leave Spain behind. Placing front and center what epic insistently marginalizes, Delicado offers a dark vision of empire: rather than celebrating conquest, the picaresque charts the messy reality that follows, from victimized exiles to a range of imperial subjects on the make and the diseases that they spread. In a world of constant circulation, whose violent exuberance exceeds the bounds of nation and empire, the pícara fabricates identities and alliances as necessary. Often chafing at her own depiction, she imaginatively relocates her own story within a canon of erotic texts. The narrator shares his protagonist’s syphilitic condition, and strains to sustain any critical distance from his subject. Delicado’s retrato thus replaces idealizing visions of imperial triumphs with a complicit narration as excessive and unbounded as its protagonist. As it chronicles the effects of syphilis on both the picaresque narrator and his subject, Lozana depicts imperialism as a ravaging, cosmopolitan disease. At the same time, the author’s own contemporary treatise on syphilis (El modo de adoperare el legno de India Occidentale, salutifero remedio a ogni piaga & mal incurabile [Venice, 1529, with a possible first edition in Rome, 1527]) underscores the connections between empire and contagion, even as it attempts to offer an epistemological grounding for the retrato.

Lozana portrays an elusive subject in a lost world, forever changed by the 1527 Spanish invasion of Rome, constantly foretold in its pages. Although the text explores central questions of place and identity, its highly wrought, selfconscious narration undoes referential understanding, foregrounding instead problems of authority, knowingness, and the text’s own worldliness.1 The intimacy of the picaresque account implicates the narrator in its telling even as it ironizes the imperial project that links Spain to Rome: although this version is insistently, intrusively authorized, it lacks insight or critical distance. My reading first traces Lozana’s richly contradictory geographical and generic coordinates. I then examine how the text systematically deconstructs narrative authority, simultaneously registering the limits of omniscience and bringing the Auctor into a tantalizing intimacy with Lozana, who has her own ideas about how to render characters and canons. Finally, I trace the contagion of syphilis between Lozana and Delicado’s contemporary treatise on the disease, to show how a highly skeptical picture of empire underlies the picaresque’s erotics.

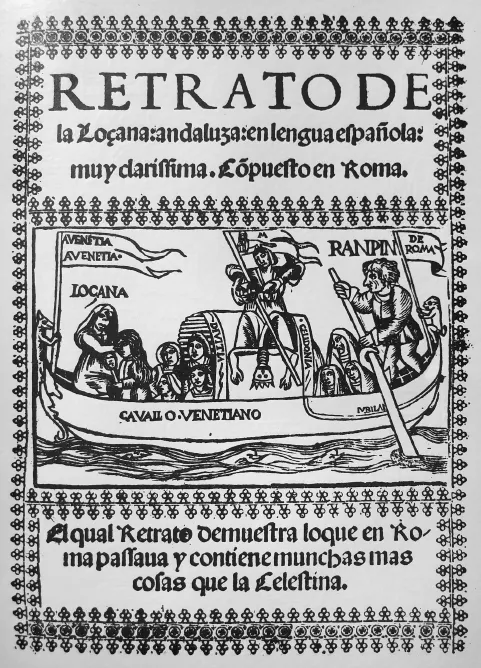

Although loosely mapped onto the life of its protagonist, the picaresque Lozana advances in fits and starts, with frequent hesitations and self-referential hiatuses, as meandering adventures stand in for any linear plot. Instead of chapters, the text is divided into “mamotretos,” a term that connotes a gathering of loose papers, imperfectly organized, or, as the concluding “Explicit” would have it, “copilaciones ayuntadas” (“coupled compilations,” with the pun on copulations).2 Despite its ribaldry and its delayed rediscovery only in the mid-nineteenth century, Lozana has by now become virtually canonical, as critics recognize its sophisticated narrative games and complex depiction of marginality. At the same time, the text’s own publication history challenges national and imperial boundaries, complicating any sense of it as a Spanish classic. The title page gives some sense of this complexity, framing the image of a ship of fools that carries Lozana and her lover Rampín from Rome to Venice with precise textual explication: “Retrato de la Loçana andaluza en lengua española muy clarissima. Compuesto en Roma. El qual Retrato demuestra loque en Roma passaua y contiene munchas mas cosas que la Celestina” [Portrait of the lusty/healthy Andalusian in the most famous Spanish tongue. Composed in Rome. Which portrait demonstrates what occurred in Rome and contains many more things than Celestina] (Figure 1). Place, language, and literary genealogy are incommensurable here: an Andalusian’s story is composed in Spanish in a polyglot Rome, while the key point of reference for the text, as for its main character, is the Spanish masterpiece increasingly known as La Celestina (1499), translated into a multilingual and transnational setting. The ship emphasizes the geographic in-betweenness of a text on the move, even as the reference to Celestina gestures toward a deterritorialized canon. From its title page, the embarked Lozana translates the bounded concerns of the earlier text—tensions among classes and castes, the status of the marginal, the erotic as an index of disorder or corruption—into a broader Mediterranean and imperial context. Lozana is most interesting precisely for how it transcends the domestic parameters of its picaresque predecessor, even as it attempts to ride the coattails of its significant success in Italy.3

Whatever its generic categorization, Lozana begs the question of its national ascription: presumably written in Rome by the Cordoban cleric Delicado, largely in Spanish but with a good dose of Italian, it was first published semi-anonymously in Venice. The documentation on Delicado is scarce: in addition to the Lozana, he published a brief treatise in Italian for priests, Spechio vulgare per li sacerdoti che administraranno li sacramenti in chiascheduna parrochia (Rome, 1525), two treatises on syphilis, De consolatione infirmorum, now lost, and El modo de adoperare el legno de India occidentale, a belated account in Italian, Spanish, and Latin of an early treatment for the disease.4 He also appears to have been active as a conduit for Spanish literature in Venice, serving as a corrector or editor for Cárcel de amor (Venice, 1531), the Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea (Venice, 1531), Amadís de Gaula (Venice, 1533), and Primaleón (Venice, 1534).5 Much of what we know about Delicado comes from his own prologues to these editions, including the claim to have authored Lozana in the introduction to the third part of Primaleón, where he also recognizes his own use of “el comun hablar de la polida Andaluzia” [“the common speech of the lovely Andalucía”] rather than of a more standard “gramatica española.”6 At the same time, he includes in his editions of Celestina and Primaleón a guide to Spanish pronunciation. Both in his relationship to language and in his self-presentation, Delicado thus appears divided among attachments to Andalucía as a region, to an expansive Spain that he may or may not subscribe to, and to an Italy increasingly permeated by Spanish fictions as by its imperial reach. The effect is of an elusive historical author scattered among his texts, however large the “Auctor” looms in Lozana.

Delicado’s canon-making and mediating functions foreground the potential of vernacular, imaginative prose as an alternative version of Spain in Italy, via a corpus of Spanish literature that upends decorum with erotic transgressions.7 When a certain “Caballero” wishes to recommend Lozana to the Neapolitan ambassador, he praises her by locating her within a vernacular and amatory tradition of Spanish vernacular texts on love: “Monseñor, ésta es cárcel de Amor; aquí idolatró Calisto, aquí no se estima Melibea, aquí poco vale Celestina” (189) [“Your honor, this is the prison of Love, here did Calisto worship, here is Melibea scorned, here is Celestina worth little”].8 Delicado’s characters thus anticipate the corpus that he himself would promote through his editorial labors. Yet the ribaldry of Lozana, as of its most signal predecessor, Celestina, does more than simply disrupt expectations, offering instead an alternative picaresque canon that is both anti-exemplary and anti-imperial.

Figure 1. Title page, Delicado, Retrato de la Loçana andaluza (Venice, c. 1528). From the facsimile edition of the unique copy at the Osterreichische Nationalbibliotek, Vienna, published with permission of Tipografía Moderna/Artes Gráficas Soler, Valencia. Photo by Rhonda Sharrah.

Despite the scarcity of sources, critics have surmised that Delicado was himself a converso who fled Spain sometime around the 1492 expulsion and sought refuge from the Inquisition in the priesthood.9 Whatever the historical Delicado’s origin, he gives his central character and his persona as Auctor/narrator a shared birthplace: both are Andalusian foreigners in Italy. The coincidence anticipates the dizzying play of self-referentiality that will characterize the text, as third-person narration breaks down into dialogue and the Auctor’s direct exchanges with his characters. Paradoxically, the closer the Auctor gets to Lozana, the less reliable he appears, while she angles for control of her own story. As the text explores the implications of their shared Spanishness in light of the imminent invasion, the picaresque narration increasingly takes on the Spanish imperial project.

Knowing Narrators

In a series of paratexts, Delicado offers a playful reflection on narrative authority. Unlike Celestina, which largely sidesteps the problem of narration via its organization into dialogue and autos, Lozana returns often to the problem of authorial knowing and telling, mixing dialogue with narration in novel ways. Lozana’s interrupted, contested narration makes visible the interrelated stakes of narrative control, embeddedness, and sympathy that give the picaresque its particular power. Sidestepping teleological accounts that would make Lozana’s uneven form an accident of its early date, or of its author’s limited possibilities, I want to recover the full complexity of Lozana’s narrative games—including but also beyond authorial intentionality.

The prologue, addressed to an “Ilustre señor,” promises “que solamente diré lo que oí y vi, con menos culpa que Juvenal” (5) [“I will only say what I saw and heard, and be less to blame than Juvenal”]. Delicado’s sly defense invokes a classical exemplum even as he claims eyewitness authority. Yet his referent is not mimetic but satiric, known for his acerbic take on life in the first imperial Rome, and its sexual foibles. Is Delicado less to blame because he relates only what he witnesses, or because in relaying it he is less biting than Juvenal? The tongue-in-cheek prologue immediately negates any claim that the text simply reports what the Auctor has witnessed:

Y como dice el coronista Fernando del Pulgar, “así daré olvido al dolor,” y también por traer a la memoria munchas cosas que en nuestros tiempos pasan, que no son laude a los presentes ni espejo a los a venir. Y así vi que mi intención fue mezclar natural con bemol, pues los santos hombres por más saber, y otras veces por desenojarse, leían libros fabulosos y cogían entre las flores las mejores. (6)

[And as the chronicler Fernando del Pulgar says, “I will thus forget pain,” and also for it will bring to memory many things that occur in our time, which do not honor those present nor serve as a mirror for those to come. And so I saw that my intention was to mix the natural with the flat, for the saints in order to know more, and also for relief, read fabulous books and chose the best among the flowers.]

The reference to Pulgar, royal chronicler for Ferdinand and Isabella, and also would-be defender of the conversos, introduces contradictory modes of telling. The national history to which Pulgar contributes is written to exclude conversos like Lozana (and possibly Delicado himself), yet here writing simultaneously memorializes and erases the pain of the excluded.10 Delicado’s irony works at multiple levels: as the editors point out, in the passage alluded to Pulgar actually notes that he cannot find consolation for old age in reading Cicero’s treatise on the same (499). The solemnity further dissolves in light of the erotic polysemy of the passage, as Delicado packs his references to music and humanist commonplaces with sexual innuendo.11 In fact, the Auctor, as a character in his own story, will have no direct contact with Lozana until Mamotreto XXIV, so his authority cannot be based on direct experience, whatever claims he makes here. His book must instead be more like those “libros fabulosos” that even the saintly pursue.

Even though the excursus into Lozana’s origins will take us further than ever from the Auctor’s direct experience of his character, the Argumento announces its interest in locating her precisely: “Decirse ha primero la ciudad, patria y linaje” (9) [“Her city, country, and lineage must first be told”]. The Auctor actually shares a Cordoban birthplace with Lozana, yet this serves primarily as an affinity, affording him no access to her early history. Nonetheless, the Argumento reiterates the prologue’s claims for authority, forbidding anyone from adding to the self-sufficient text:

Protesta el autor que ninguno quite ni añada palabra, ni razón, ni lenguaje, porque aquí no compu...