![]()

CHAPTER 1

Images in Lava

Felicia Hemans, Sentiment, and Annotation

I

In the fall semester of 2009, I asked the students in my graduate seminar on nineteenth-century British poetry at the University of Virginia to go into the stacks of our research library and find a nineteenth-century copy of Felicia Hemans’s poetry to bring to class. The idea was to leave behind the modern anthologies and see what Hemans’s poetry looked like in its original formats. After all, Hemans was one of the most popular poets of that era, and I wanted us to consider that fact at the level of media, examining books as they had appeared to her readerships across the century.1 I knew that our library—like many academic libraries—had a large number of Victorian editions in the circulating collection. Neither rare nor up-to-date, these books exist in a kind of institutional shadow-land, somewhere between the valuable first editions and the efficient modern ones. I had a sense they might have things to tell us about Hemans that were otherwise occluded. But the assignment was a mere impulse, not well theorized. And it ran athwart standard bibliographical practice in its embrace of randomness and its leveling of editions: the students were being asked to follow their noses, not seek out specific volumes to describe and assemble into genealogies. Any Hemans volume printed before 1900 would do. More exceptionally, they were being asked to do their research in the circulating collection, the open stacks. The vast majority of scholars interested in bibliography and book history do their work in special collections and rare-book rooms. In those contexts, one encounters volumes already recognized as important in any number of ways: rare, early, valuable, owned by the famous. Indeed, if I had thought more clearly, or planned ahead, we undoubtedly would have looked at the Hemans books in our special collections instead, comparing early editions, looking at well-curated, carefully preserved copies. But then we would not have made the discoveries that underlie this chapter and, ultimately, this book.

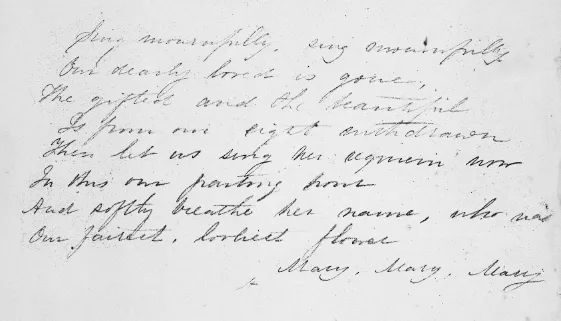

As the students talked about the books in front of them, they gravitated to the bookplates, library stamps, pen and pencil markings, and written inscriptions, most of which I was ready to dismiss as irrelevant afterformations, even damage. After all, these were circulating library books, vulnerable for decades to the shocks and scars of shelf life at a busy university. But one of the volumes brought us up short: a battered 1843 edition of The Poetical Works of Mrs. Felicia Hemans, published in Philadelphia by Grigg & Elliot. A student pointed to a poem written in pencil on the rear free endpaper and asked, “What’s this?” (Figure 2):

Sing mournfully, sing mournfully

Our dearly loved is gone.

The gifted and the beautiful

Is from our sight withdrawn.

Then let us sing her requiem now

In this our parting hour

And softly breathe her name, who was

Our fairest, loveliest flower

Mary, Mary, Mary

It was a poem in Hemans’s own style (adapting lines from “The Nightingale’s Death-Song” and “Burial of an Emigrant’s Child in the Forests”), written in pencil in nineteenth-century cursive and clearly the work of the book’s original owner: she had inscribed her name in the same hand on the title page, “Ellen Pier-repont / 1846.”2 Our first thought was that it might be a transcription of an obscure poem by Hemans or another poet, but online searches turned up nothing. More searching led us to family genealogies, and we determined that Ellen Pier-repont had married James Monroe Minor in 1847 and had had a daughter Mary (her third), who was born in 1855 and died at the age of seven.3 The poem was an elegy for her. As this story emerged, I think all of us in that classroom knew we had made contact with a life, had glimpsed a moment in the history of reading, the import of which we felt but had yet to understand. We had touched the edge of something, being ourselves touched by a fragment of a much larger archive that had been occluded by the protocols of our discipline and institutions.

The discovery of this volume and its inscriptions was necessarily accidental: marks in books in the circulating stacks are uncatalogued and often thought of as damage or graffiti. Further, the conditions for our explication of the volume’s history had only just emerged in 2009. On the one hand, we needed the plenitude of physical books in the open stacks: the multiple, historically layered copies of the same content (Hemans’s poetical works) available for browsing, cross-comparison, and serendipitous discovery. On the other, in order to determine the originality of the elegy for Mary Minor and to discover the details of the Pierrepont and Minor families, we needed Google Books, HathiTrust, and large-scale genealogical sites like Ancestry.com, which did not exist even five years earlier. If we had found the book then, we would have been uncertain how to proceed: the task of unearthing the histories of both poem and family would have been too daunting. Yet we were able to do that research on the fly, in the classroom, from our laptops. It was the synthesis of two types of searching—one among the books in the stacks and another among massive text repositories and databases online—that brought this volume to life. And if we had waited much longer, the books might not have been there: older print collections across the nation’s academic libraries are currently being moved off-site, consolidated, and downsized, particularly in the wake of the large-scale digitization projects that have made nineteenth-century content so readily available online.4

Figure 2. Inscription on rear endpaper of The Poetical Works of Mrs. Felicia Hemans (Philadelphia: Grigg & Elliot, 1843). Ellen Pierrepont Minor’s copy. Alderman Library, University of Virginia. PR 4780 .A1 1843.

But what is “nineteenth-century content” after all? My students’ discovery made very clear the difference among copies as well as the importance of these books as individual scenes of evidence in the history of reading and book use. Marked copies offer rich data for literary historians, but their work has mostly stopped short of the nineteenth century.5 Yet readers continued to write in books, many of which are now held in circulating library collections. As library patrons increasingly turn to online surrogates for nineteenth-century texts, and as libraries reconfigure their collections as distributed, collective networks of content rather than copy-specific collections, these unique books are under a general threat of loss. In a related way, as scholars write literary histories based on the reading of abstracted printed texts—whether in modern anthologies or large digital data sets—they elide the individual bibliographic features fundamental to literature as a cultural activity. In this chapter and those that follow, I mean to give a copy-specific inflection to the study of reader response and affect, and to make the case for intimate micro-reading as a counterweight to both New Critical modes of close reading that assume an objective stance and to the distant reading of the nineteenth century now well under way in the digital humanities. In the background, you should hear an implicit call for the retention of physical books in libraries, not out of mere sentiment but predicated on a renewed attention to them as objects and interfaces with sentimental histories of their own. As we will see, Hemans turns out to be an ideal author with whom to pursue such a project.

A number of the other Hemans volumes we looked at that day had names, dates, inscriptions, and marginalia clearly placed there by nineteenth-century readers. But the elegy for Mary Minor haunted us, in part because we had just read Hemans’s poem “The Image in Lava,” with which it seemed to resonate heavily. In a note, Hemans describes its subject: “The impression of a woman’s form, with an infant clasped to the bosom, found at the uncovering of Herculaneum”—that is, a concave imprint of the ancient bodies of a mother and child preserved in rock after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius:

Thou thing of years departed!

What ages have gone by,

Since here the mournful seal was set

By love and agony!

Temple and tower have mouldered,

Empires from earth have passed

And woman’s heart hath left a trace

Those glories to outlast!

And childhood’s fragile image

Thus fearfully enshrined,

Survives the proud memorials reared

By conquerors of mankind.6

In the context of Ellen Pierrepont Minor’s copy of Hemans, “The Image in Lava” seemed to be about that book itself, a “thing of years departed” set with “the mournful seal” of the elegy, Mary Minor’s “fragile image / Thus fearfully enshrined.” “Woman’s heart” had “left a trace” in this book, which we encountered in a spirit of sympathetic and even sentimental awe. This inscribed book had surprised us and drawn us into the imaginative field of Hemans’s poetics, a field far wider and deeper than we had imagined.7

“The Image in Lava” models a certain kind of encounter with material from the past. We might call it sympathetic reading—part evocation, part projection—of the kind we now were practicing with a mother’s handwritten elegy for her daughter. As Brian P. Elliott has written of the poem, “The poet creates a space for the speaker’s elegiac personal mourning by ‘emptying’ the central objects of meaning. …Hemans creates objects of contemplation that are ciphers…whose impersonal nature opens up the possibility of intensely personal investment.”8 Hemans’s mother had died in 1827, the year in which she wrote “The Image in Lava.” Reading about the impression of the mother and child, Hemans fills in the gaps, expanding the reference by investing it with personal emotion drawn from her recent experience. In so doing, she makes the “print upon the dust” refer to her own biography and feelings. As a matter of disciplinary expertise, we typically discourage this mode of reading by our students, who often want literature to be relatable, to refer to their own emotional experiences.9 We urge instead objectivity and hermeneutical rigor, leading them from alienation to tentative mastery by means of careful reading, theorizing, and research. But now we were outside those protocols, in the midst of a layered scene of identification and sentiment: Hemans with her ancient monument, Pierrepont with Hemans’s poetry, and our class with Pierrepont’s book.

Recent theoretical work has addressed the relation between such responses and the enterprise of literary criticism. In Theory of the Lyric (2017), Jonathan Culler urges us to question “the presumption that poems exist to be interpreted,” and to develop new—or rediscover old—models of reading lyrics: we might “take them to illuminate the world” rather than using them as occasions for hermeneutic elabo-ration.10 Mary Louise Kete’s work on sentimental collaboration, in which she rejects the idea that sentimentality involves merely “a sham display of emotion,” provides another framework here.11 Reading a different mourning poem written by a nineteenth-century mother for her dead child, Kete finds that “the distinguishing function of the poetics of sentimentality is … to reattach symbolic connections that have been severed by the contingencies of human existence” (6). Pierrepont’s plural pronouns—“let us sing her requiem now / In this our parting hour”—partake of this collaborative sentimental dynamic, evoking a community of mourners (call it a family) that may sing aloud and together the very poem now being read silently and alone. Marks in books of poetry cross this divide of private and public affective response. Karen Sánchez-Eppler writes that while “the loss of a child must be one of the most intimate of griefs, … the myriad of nineteenth-century child elegies suggests that the death of a child serves a public function as well,” articulating “anxieties over the commodification of affect” in that culture.12 The mid-nineteenth century, she writes elsewhere, saw the rise of various cultural practices involving poetry (such as making scrapbooks and sending greeting cards) predicated on the idea that “someone else’s words … might provide the best expression of private feeling.”13 For me and my students, this copy of Hemans authorized our own sentimental collaborations in the classroom.

Pierrepont’s book also exposes a tension in Hemans criticism, since modern literary historians have at times been disdainful of Hemans’s nineteenth-century readers. Susan J. Wolfson writes that the recovery of Hemans “has been a project of rescuing her from the terms of her nineteenth-century popularity.”14 Stephen C. Behrendt similarly identifies “the central problem in ‘Hemans studies’: the split between the famous sentimentalized poet, ‘Mrs. Hemans,’ and the largely unappreciated interrogator of cultural practices [and] cultural assumptions.”15 Beginning with Tricia Lootens’s article in 1994, several influential studies have stressed the fierce complexities of Hemans’s imagination, presenting her as a subtle critic of patriarchal violence and the costs of empire, even amid her ostensible domestic commitments that her Victorian reviewers praised.16 David E. Latané has pointed out the contradiction in our implicit dismissal of the readers that made her one of the most popular poets of the century: “If we are going to teach Hemans against the grain, demonstrating how her poetry may be seen to be socially progressive, feminist, or more ironic than presumed, then raising the issue of popularity causes problems of intentionality because we must then assume … Hemans’s readers did not know how to read her.”17 Now, confronted with a book owned, read, and marked by one of those readers, we realized we might be in a better position to produce a sympathetic account of Hemans’s popularity and to get a purchase on the affective dynamics of her work—a project begun by Marlon Ross but never much pursued according to the responses of individual readers.18

But we needed to know more. A little research revealed that Pierrepont’s collected edition of Hemans, produced by the Philadelphia publisher Grigg & Elliot, was a very common book: first stereotyped in 1836 and augmented and reprinted almost annually for several decades, Grigg & Elliot editions became perhaps the most common and affordable editions of Hemans’s collected work for nineteenth-century Americans.19 We also discovered that the University of Virginia holds another copy, in special collections, published in 1839 and inscribed “To Charlotte M. Cocke… from a friend, Xmas 1840.”20 Charlotte Cocke annotated it lightly, marking about a dozen poems with signs of emphasis. But on one page, the level of attention increases radically: underlining, brackets, check marks, and exclamation points erupt across the text of “The Graves of a Household,” especially around t...