![]()

Chapter 1

History and Place

Hometown, Local Knowledge, and National Politics

Geese, geese, endless geese.

—C. A. Macartney (1934)

Certainly in a place as small as Konitz, one knows with whom one is speaking.

—Presiding judge, Konitz criminal court (1900)

Toward a Cultural Geography of Place

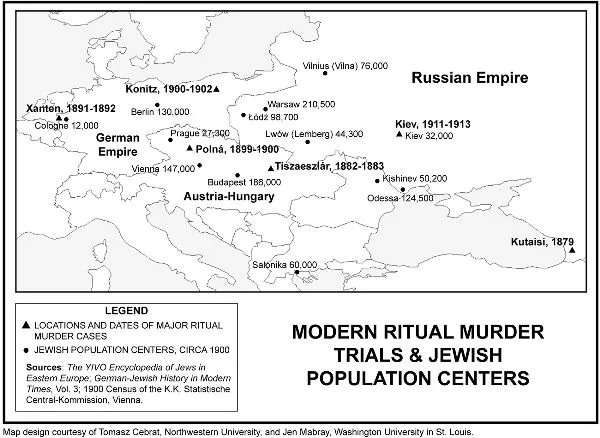

On the morning of 2 June 1891, in the Rhineland town of Xanten, the mother of Johann Hegmann, aged five, sent her son outside to play so that she could attend mass in commemoration of the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. As one might already have guessed, the boy never returned home, and the tragic discovery that evening of his stabbed and bloodied body set in motion a series of events, which culminated in Germany’s first formal trial on the charge of ritual murder since the sixteenth century.1 Finding himself accused of Johann’s murder—presumed to have been carried out for the purposes of violent, anti-Christian Jewish ritual—was Adolf Buschhoff, aged fifty, a native of Xanten and one of the town’s eighty-five Jewish inhabitants. A former ritual slaughterer for the Jewish community who more recently had been working as a stonecutter, Buschhoff had enjoyed an impeccable reputation as a friendly and mild-mannered citizen of the town almost up to the moment of his becoming the target of suspicion.2 The obvious question is, why? Why does an apparently well-adjusted, sociable, and esteemed member of a small urban community become the prime target of a murder investigation? Why was this murder so quickly and easily understood as a crime committed by Jews acting under religious compulsion? And what is the process by which this discursive transformation happened?

Similar questions can be raised with regard to other long-standing and ostensibly well-integrated Jewish citizens of towns and villages in Germany and Austria-Hungary whose lives and sense of belonging were uprooted when they became embroiled in ritual murder proceedings: József Scharf, Salamon Schwarcz, and thirteen others in and around Tiszaeszlár; Adolf and Moritz Lewy in Konitz; and perhaps even Leopold Hilsner, the underemployed ne’er-do-well who spoke German and Czech with equal ease and spent most of his days with likeminded Christian Czechs in Polná.3 How exactly did Jews relate to their local towns and villages in Central Europe during the last decades of the nineteenth century? In what ways were their lives transformed—if at all—by the political emancipation that had become enshrined in law between 1867 and 1871? Was their supposed integration a sham? Did they feel at home in their local environments? What were the means by which intercommunal bonds were shattered?

We got a sense in the Introduction of the many articulations of the renewed blood libel that surfaced in Central Europe’s political sphere and mass-market publications. This might suggest that what we are observing is a situation in which a single cultural phenomenon takes root more or less simultaneously across a variety of political and geographic settings. If that is true, then one might argue that any explanation of this phenomenon must necessarily be comparative, giving weight to common features and general patterns. What do the various settings have in common? What political, economic, or social factors are replicated across discrete borders? Are we dealing with a specific type of Jewish community, a particular pattern of Jewish-Gentile interaction, or a single, generalized, historical crisis?

This would certainly be a valid approach, but it is nevertheless potentially distorting, for it presumes that local conditions and the texture of local experience can adequately be understood as mere instantiations of a general pattern. The universal, in other words, trumps the specific. What I hope to do in this and following chapters, in contrast, is to engage in a type of analysis in which place, locality, and the texture of local experience are given equal weight to general, overarching patterns. A cultural geography of place, if you will, is interested in specificity: the physical landscape of a village or a town, local patterns of economic exchange, the distribution of power, and the creation of knowledge. Such an approach embodies the tension between the drive to compare—and hence to emphasize pattern—and the appreciation of uniqueness. It seeks to “enter” the landscape, to uncover the texture of local experience, to capture the perspectives of local actors. It asks of what importance local cultural understandings are to historical processes, or the intrinsic patterns of social relations to political affairs. Finally, it attempts to disengage the modern ritual murder trial, as a cultural phenomenon in which Jews and Gentiles vied with each other and over their own sense of self, from antisemitism as an explanatory construct.4

At the level of everyday experience, accusations of ritual murder emerged both from social interactions and from the ensuing moral constructions that imbued events with meaning. They were the products of face-to-face encounters—scripted in part by cognitive expectations—each of which added something to the local complex of social knowledge. One could say that the modern ritual murder accusation, whatever else it might have been, was born of, and nurtured by, community. But what kind of community? In virtually every instance, the local setting turns out to have been a village or, more likely, a market town; rarely, a small city. In other words: paradoxically tranquil places whose traditional economic and social structure stood at some remove from the wide-ranging transformations typically associated with the industrial age. Each locality also possessed a long-standing Jewish community, historically rooted to the environment, fully conversant in the surrounding culture, and—by all appearances—on relatively cordial, if not intimate, terms with its Christian neighbors. In each instance, too, the transition from a concrete narrative of Jewish ritual murder to police investigation and trial entangled the town or village in an expansive web of urban discourses and political processes (in the form of newspaper coverage, parliamentary interpellations, and the invasion of journalists and national politicians). The present chapter seeks to disentangle this complex relationship when possible, at the very least to give play to the tension inherent in the not always comfortable distinction between the local and the universal.

The places in question, then, were small, of such a scale that social relations usually involved face-to-face interactions. Tiszaeszlár, which lies in the northeastern stretch of Hungary’s Great Plain in what was then Szabolcs County (county seat, Nyíregyháza), is arguably the only true village among our sample. It sits on the left bank of the Tisza River nestled between two dominating towns: Debrecen to the south and Szatmár (later, Satu Mare in Romania) to the east.5 It was in villages such as Tiszaeszlár that nationalist historians of the nineteenth century claimed to have discovered the cradle of a nation’s values and character. No less a figure than the British historian C. A. Macartney, observing Hungary in the 1930s, went so far as to describe the villages of the Great Hungarian Plain as incorporating “the social and economic ideals of the true Magyar.” His portrait stressed the tranquility and banality of the Hungarian village and the predictability of its physical features.

The village itself is a regular pattern of very wide streets, most of them unpaved, the basking-place of pigs and poultry and geese, geese, endless geese; and bounding the street, rows of little whitewashed, one-storied houses, each with its narrow end turned to the street, while between its verandahed face and its neighbor’s back, is a sandy courtyard, a well, a few sunflowers. Behind, opening straight onto the fields, are byres, barn, and stable. It is a community which reeks of the soil. Every man in it, from the local magnate downward, lives by, on, and from the soil. The fields stretch up to the very doors, and the fruits of them are scattered in the courtyards. The few craftsmen, who advertise their skill by a painted sign of smock, boot, or scythe, the cobbler, smith, and tailor, are themselves most often peasants who ply their trade in their spare hours.6

Midsized market towns served as the setting for subsequent ritual murder accusations as well as for the criminal investigation and trial in the Tiszaeszlár case. In Macartney’s view, places such as these amounted to little more than glorified villages in any event. True, their level of economic and administrative activity might have required the presence of a police barracks and a town hall, a few bank branches, and a local doctor (not to mention the ubiquitous inns). But social life in the market towns was structured largely along rural lines. As late as the 1930s, a high proportion of town inhabitants was made up of landowners, many of whom were in fact peasants who went out into the fields during the day; others were owners of estates in the country on which they spent much of their time.7

Xanten appears to have been such an “oversized village.” Located in Imperial Germany’s Lower Rhine Plain in the state of Prussia (the Rheinprovinz), the town was once a Roman river crossing along the main road that ran from Cologne to Cleves and Nijmegen. But Xanten lost much of its economic importance with the subsequent shifting of the course of the river.8 Between 1875 and 1910, its population grew modestly from 3,292 to just under 4,300; Düsseldorf, in contrast, the seat of the main administrative subdivision (Regierungsbezirk) to which Xanten belonged, had almost 360,000 inhabitants; Cologne, the capital of the neighboring Regierungsbezirk, had a population of 600,000.9 The Lower Rhineland consisted largely of isolated farmsteads and towns that dated back to the thirteenth century. Robert Dickinson’s postwar geographic guide to Germany commented that the only flourishing towns in the region were those that enjoyed both rail transport and direct contact with the Rhine. Xanten was not one of these. With no industry of its own and no direct link to the river’s traffic, it remained a local market center and appeared to have preserved much of its medieval flavor.10

It was this sense of a town resting in suspended animation that Paul Nathan, sent by the Berlin newspaper Die Nation to cover the Xanten trial, tried to convey for his readers back home. The reporter paused on his approach to the town to capture the visual impact of the place as it hovered in the distance, contrasting so starkly from the cityscape of the modern metropolis. The town that lay before him seemed to evoke the German past, entangled in bucolic serenity and stern, medieval, Catholic grandeur.

Xanten—it lies so beautiful. Lost in greenery, the small, neat houses surround the mighty cathedral, the gothic St. Victor’s Church, a towering presence, one of the most serious and memorable medieval constructions on the Lower Rhine. As one stands on the gently rising Fürstenberg and looks over the landscape at the clusters of green trees, the small patches of forest, the farms and villages, the gentle hills and the wide, flat plains, through which the Rhine flows wide and steel gray; and as one’s eye is drawn again and again to the powerful mass of the cathedral, it seems as though the ruling power of the Middle Ages stands there as a bodily presence.11

Polná, the site of the Hilsner case, offers a variation on the theme of the small town left behind by industrialization. Situated along what was once an important road to Hungary, Polná occupies a corner of the Bohemian-Moravian highlands (Českomoravská vysočina), an extensive, wooded plateau that straddles the border between Bohemia and Moravia, the two major provinces of the Czech lands. Two larger, neighboring towns—Jihlava (Iglau) and Německý (later, Havličkův) Brod (Deutschbrod)—achieved fame as centers of silver mining in the thirteenth century, while Polná itself—owned by a succession of noble families—was more closely tied to the organization of feudal property up to the middle of the nineteenth century. The town also felt the tumultuous effects of the revolt of the Czech estates against imperial rule at the start of the Thirty Years War. Its owners from the late sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries had been Protestant, members of the Zejdlič of Šenfeld family, who (as Protestants) had lent their support to the unsuccessful revolt of the Czech estates of 1618 to 1620. They lost their lands with the suppression of the revolt, and in 1623, the Bishop of Olomouc, František (Franz) of Dietrichštejn, acquired the feudal rights to the town from Emperor Ferdinand II for 150,000 zlaty. The Dietrichštejn family ruled Polná (admittedly, from a distance) until 1848 and maintained large tracts of land there until 1922.12

Although technically part of Bohemia, Polná lies stubbornly to the east of the closest large town in the region, Jihlava (Iglau), which is in Moravia. This geographic curiosity suggests a remoteness from Prague, the cultural, political, and economic center of Czech life—a remoteness underscored by the mapping of industrialization in the region. In 1871, when the first rail lines connecting Prague, Jihlava, and Znojmo were opened, they bypassed Polná altogether, coursing six kilometers from the outskirts of the town.13 In 1890, one could find a five-grade lower school (obecní škola) for boys and one for girls; one three-grade měšt’anská škola (Bürgerschule) for each of the two sexes, geared toward trade and commerce; and a two-grade Jewish school. Polná’s population at the time stood at 9,102, of whom 8,801 were Catholic, 247 Jewish, 44 Protestant, and 10 “other.” The village of Malá Věžnice, which would feature prominently in the events of 1899 to 1900, lay to the northwest of the town. It comprised forty homes, a population of 218, and a one-grade school.14

Konitz (Chojnice)—the largest of the towns that produced ritual murder trials around 1900—lies in the formerly German province of West Prussia, to the south and east of Pomerania. This is territory that has alternated between German and Polish political control. Before 1772, it belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and was administered by the Polish Crown as part of the territory of what was called “Royal Prussia.” Following the first partition of Poland-Lithuania, it was attached to the Kingdom of Prussia, and both “Royal Prussia” and its neighbor to the east, the province of “Prussia,” were renamed: the former became West Prussia; the latter, East Prussia. From the 1820s to 1878, East and West Prussia were combined administratively; from 1878 to the end of World War I, they were again organized as separate entities, with Danzig (Gdańsk) serving as the West Prussian capital and Königsberg (Kaliningrad) that of East Prussia. After 1918, Konitz/Chojnice was located in the Polish Republic.15

Unlike the case in the much smaller Polná, the all-important railway lines did not skirt past this West Prussian town. In fact, Konitz was a stop on two important railway lines: one, which ran from eastern Pomerania toward the southeast, and the other, the main line from Berlin to Danzig (Gdańsk). Not isolated, to be sure, Konitz appears in most other respects to have been completely unremarkable. According to the Baedeker travel guide, the junction of the two rail lines constituted the town’s only point of interest.16 A more distinctive feature of Konitz was its setting in an ethnic and religious borderland. West Prussia comprised a mixed German and Slavic, as well as Protestant and Catholic, population. In 1858, 69.1 percent of its inhabitants were counted (by language) as Germans and 30.9 percent as Slavs. By 1910, the number of Germans had declined somewhat to about 65 percent (equal to 1,100,000 individuals). Of the 35 percent who claimed Slavic ethnicity, 475,000 indicated Polish as their mother tongue and 107,000 Kashubian. About 22,000 people were listed as bilingual.17 In the city of Konitz itself, there were 10,656 inhabitants in 1895; of these, 4,974 were Catholic, 5,358 Protestant, and 480 (4.5 percent) Jewish. While the surrounding countryside was made up of Germans, Poles, and Kashubians (to the north and east), the town itself was populated overwhelmingly by Germans.18

Jews, State, and Society in Germany and Austria-Hungary: Historical Patterns

Despite the lyrical depictions by Nathan and Macartney of an almost timeless village and small-town life in Central Europe, these localities were never frozen in time. Their populations may not have grown appreciably. Their economies may indeed have declined since the onset of industrialization, but they were nevertheless deeply marked by the transformations in social structure, politics, and the economy that had taken place since the last decades of the eighteenth century. They were, in other words, artifacts themselves of modern times. In Hungary, important transforma...