- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

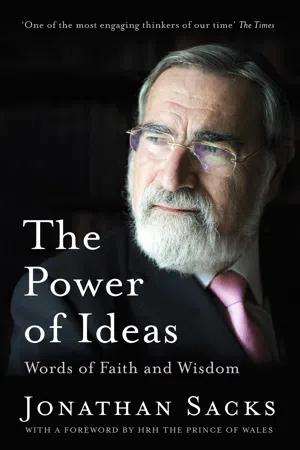

Britain's most authentically prophetic voice - The Daily Telegraph 'The choice with which humankind is faced is between the idea of power and the power of ideas.' From his appointment as Chief Rabbi in 1991, through to his death in November 2020, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks made an incalculable contribution not just to the religious life of the Jewish community but to the national conversation - and increasingly to the global community - on issues of ethics and morality.Commemorating the first anniversary of his death, this volume brings together a compelling selection of Jonathan Sacks' BBC Radio Thought for the Day broadcasts, Credo columns from The Times, and a range of articles published in the world's most respected newspapers, along with his House of Lords speeches and keynote lectures.First heard and read in many different contexts, these pieces demonstrate with striking coherence the developing power of Sacks' ideas, on faith and philosophy alike. In each instance he brings to bear deep insights into the immediate situation at the time - and yet it as if we hear him speaking to us afresh, giving us new strength to face the challenges and complexities of today's world.These words of faith and wisdom shine as a beacon of enduring light in an increasingly conflicted cultural climate, and prove the timeless nature and continued relevance of Jonathan Sacks' thought and teachings.One of the great moral thinkers of our time - Robert D. Putnam, author of Bowling Alone

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword By HRH The Prince of Wales

- Introduction

- Part One

- Religious Tolerance and Globalisation

- The Age of Greed

- Holocaust Memorial Day

- Interfaith Relations

- A Royal Wedding

- The King James Bible

- The Council of Christians and Jews

- Leadership

- The Fragility of Nature

- Belief and Rituals

- Margaret Thatcher

- The Danger of Power

- Free Speech

- Faith

- Birdsong

- Shame and Guilt Cultures

- Taking Democracy for Granted

- Religion’s Two Faces

- The Good Society

- The Impact of Social Media

- Handling Change

- Disagreement and Debate

- Antisemitism

- Loving Life

- Confronting Racism

- Love

- The Coronavirus Pandemic

- Part Two

- Charity

- Marriage

- Listening

- Religious Fundamentalism

- Terrorism

- Natural Disasters

- Religion and Politics

- Volunteering

- Prayer

- Armistice Day

- Failure

- Resolutions

- Climate Change

- Contracts and Covenants

- The Probability of Faith

- Crisis

- Religion and Science

- What Religions Teach Us

- Faith Schools

- Books

- Jewish Advice

- Achieving Happiness

- A Life Worth Living

- Parenthood

- Faith

- Part Three

- Reflections: One Year On

- All Faiths Must Stand Together Against Hatred

- Reversing the Decay of London Undone

- The 9/11 Attacks Are Linked to a Wider Moral

- Has Europe Lost Its Soul to the Market?

- The Moral Animal

- What Makes Us Human?

- If I Ruled the World

- A New Movement Against Religious Persecution

- A Kingdom of Kindness

- Nostra Aetate: Fifty Years On

- The Road Less Travelled

- Beyond the Politics of Anger

- Morality Matters More Than Ever in a World

- Part Four

- Queen’s Speech (Maiden Speech)

- Faith Communities

- Religion in the United Kingdom

- Business and Society

- Middle East and North Africa

- Freedom of Religion and Belief

- National Life: Shared Values and Public Policy

- Balfour Declaration Centenary

- Education and Society

- Antisemitism

- Part Five

- A Decade of Jewish Renewal

- Markets and Morals

- Forgiveness and Reconciliation

- The Good Society

- The Five Cs Essential to Our Shared Future

- Insights from the Bible into the Concept of

- On Freedom

- Faith and Fate

- A Gathering of Many Faiths

- A New Chief Rabbi

- On Creative Minorities

- The Love That Brings New Life into the World

- The Danger of Outsourcing Morality

- The Mutating Virus

- Facing the Future Without Fear, Together

- List of Published Works by Jonathan Sacks

- Footnotes

- Endmatter page 1

- Imprint Page