- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

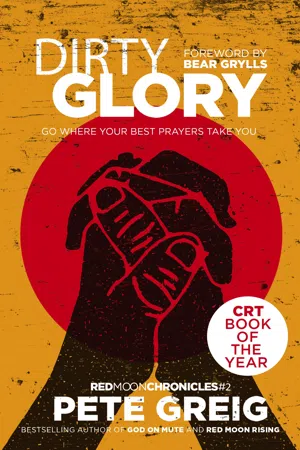

Winner - Book of the year, CRT awards Foreword by Bear Grylls Following on from the success of Red Moon Rising, which tells the story of the first five years of the 24-7 prayer movement, Dirty Glory describes stories of transformation, from a walled city of prostitution in Mexico to the nightclubs of Ibiza, and invites people to experience the presence of God through prayer. An autobiographical adventure story spanning four continents, describing one of the most exciting movements of the Holy Spirit in our time, Dirty Glory will inspire and equip those dissatisfied with the status quo and passionate about the possibilities for spiritual and social transformation in our time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dirty Glory by Pete Greig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Punk Messiah

The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.

We have seen his glory …

(John 1:14)

God’s story from beginning to end describes glory getting dirty and dirt getting blessed. The Creator made humanity out of the dust and if, on that day, we left a little dirt behind in the creases of his hands, it was surely a sign of things to come.

When God made us again, he came first to a teenage girl, and then to unwashed shepherds and later to pagan astrologers. God spoke the gospel as a dirty word into a religious culture. ‘The Word’, we are told by John at the start of his Gospel, became ‘flesh’. The Latin used here is caro, from which we get ‘carnivore’, ‘incarnation’, ‘carnival’ and even ‘carnal’.1 God became a lump of meat, a street circus, a man like every man.

John is messing with our minds. He knew perfectly well that this opening salvo was a shocking, seemingly blasphemous way to start his Gospel. Like Malcolm McLaren, Alexander McQueen or Quentin Tarantino, he is grabbing attention, insisting upon an audience, demanding a response. ‘In the beginning,’ he says, echoing the opening line of the Bible, lulling us all into a false sense of religious security.

At this point, I imagine John pausing mischievously, just long enough for every son of Abraham to fill in the blanks incorrectly.

‘In the beginning’, he continues, ‘was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ It’s the familiar creation narrative outrageously remixed, featuring a mysterious new aspect of the divinity named, like some kind of superhero in a Marvel comic, The Word.

And yet for John’s Greek readers – the vast majority of Christians by the time the Gospel was written2 – the Word was not a new concept at all. For them this was the familiar Logos of domestic philosophy, that divine animating principle pervading the cosmos. The bewildering thing for their ears would have been John’s emphatic conflation of this pagan Greek notion of divinity with the Creator God of Jewish monotheism: ‘The Word’, he says unambiguously, ‘was God.’

And so, in just these first thirty words of his Gospel, John has effectively both affirmed and alienated his entire audience, Greek and Jew alike. And then, like a prizefighter in the ring, while we are all still reeling from this first theological onslaught, John lands his body blow: ‘The Word’, he says, ‘became flesh.’

It’s a breathtaking statement, equally appalling for the Jews who had an elaborate set of 613 rules to help segregate holiness from worldliness, but also for the Greeks who despised the flesh with its malodorous suppurations and embarrassing, base instincts. ‘The Word became flesh.’ Imagine the intake of breath, the furrowed brows, the wives looking at their husbands silently asking, ‘Did he just say what I think he said?’ and the husbands glancing towards their elders wondering, ‘Is this OK?’ It’s punk-rock theology. It’s a screaming ‘hello’.

‘The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us and we have seen his glory.’ One scholar says that this is ‘possibly the greatest single verse in the New Testament and certainly the sentence for which John wrote his gospel’.3 God’s infinite glory has moved, as Eugene Peterson says, ‘into the neighbourhood’. He has affirmed our humanity fully. He has identified with us completely, in our joy but also in our pain.

‘God made him who had no sin to be sin for us.’ The Word didn’t just pretend to become flesh. He wasn’t fraternising with humanity from a morally superior plane. Jesus became sin for us, ‘so that in him we might become the righteousness of God’ (2 Cor. 5:21). This is the staggering message of Christ’s incarnation: God’s glory became dirt so that we – the scum of the earth – might become the very glory of God.

This then is our creed. We believe in the blasphemous glory of Immanuel; ‘infinity dwindled to infancy’, as the poet once said.4 We believe in omnipotence surrendering to incontinence, the name above every other name rumoured to be illegitimate. We believe that God’s eternal Word once squealed like a baby and, when eventually he learned to speak, it was with a regional accent. The Creator of the cosmos made tables and presumably he made them badly at first. The Holy One of Israel got dirt in the creases of his hands.

Here is our God – the Sovereign who ‘emptied himself out into the nature of a man’, as one popular first-century hymn put it (see Phil. 2:7). The Omniscience who ‘learned obedience’, as the book of Hebrews says (5:8). The King born in a barn. The Christ whose first official miracle took place at a party involving the conversion of more than a hundred gallons of water into really decent wine. Two thousand years on, and some religious people are still trying to turn it back again. And of course it was these same people who accused him at the time of partying too hard. Rumours followed him all the days of his life, and he did little enough to make them go away.

Perfectly dirty

You probably remember the story about Jesus asking a Samaritan woman with a dubious reputation for a drink (as if he didn’t know how that would look). And how he recruited zealots, harlots, fishermen, despised tax-collectors and Sons of Thunder. And how he enjoyed a perfumed foot-rub at a respectable dinner party. One scholar says of the woman in this particular encounter, ‘her actions would have been regarded (at least by men) as erotic. Letting her hair down in this setting would have been on a par with appearing topless in public. It is no wonder that Simon [the host] entertains serious reservations about Jesus’ status as a holy man.’5 Jesus made himself unclean again and again, touching the untouchables: lepers, menstruating women and even corpses. He got down on his knees and washed between the toes of men who’d been walking dusty roads in sandals behind donkeys.

And while the dirt lingered in the creases of his hands, he accused those whose hands were clean of sin. Did you hear the one about the whitewashed tombs (Matt. 23:27)? Or about the dutiful son who despised the prodigal brother staggering home penniless and covered in pig (Luke 15:30)? Or the story about the dirty low-life tax-collector whose snivelling apologies were heard by God while the precise intercessions of a righteous Pharisee merely bounced off the ceiling (Luke 18:9–14)? The Word told dirty stories, and the stories told the Word.

Offended, they washed their hands of him – Pontius Pilate, the Chief Priest, even Simon Peter – and they hung him out to die: a cursed cadaver; a carpenter pinned to clumsy carpentry in the flies of that Middle Eastern sun. Eventually it was extinguished: the sun and the Son. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. Glory gone the way of all flesh.

WE BELIEVE IN THE WORD MADE FLESH WHO DWELT AMONG US AS A KIND OF PRAYER, AND SENDS US OUT TO SPEAK THE ‘AMEN’ IN EVERY DARK CORNER OF HIS CREATION.

But the dirt could not contain him for long. Three days later the sun rose and the Son rose. And now that he could do anything, go anywhere, what would he do and where would he go? Out of the whole realm of creation, the entire populace of humanity, Jesus chose to appear first to a woman. A woman in a chauvinistic culture that refused to teach women the Torah and discounted their testimony in a court of law. Mary Magdalene was a colourful woman, a woman with a questionable reputation from whom seven demons had been cast out. It was the biggest moment of her life and yet at first, embarrassingly, she mistook the resurrected Jesus for an ordinary gardener, a man with the earth ingrained in the creases of his hands at the start of a working day. Yet he had chosen her quite deliberately, another Mary for another birth, another Eve in another garden, to be his first apostle.6 This too is offensive to some to this day.

Yes, we believe in the Word made flesh who dwelt among us as a kind of prayer, and sends us out to speak the ‘Amen’ in every dark corner of his creation. He hand-picks dim-witted people like us: ‘the foolish things of the world to shame the wise’ (1 Cor. 1:27). Bewildered by grace we go wherever he sends us, eat whatever is put before us, kneel in the gutter, make the unlikeliest locations places of prayer. We participate fervidly in a morally ambiguous world, carrying the knowledge of his glory ‘in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us’ (2 Cor. 4:7).

And so, with angels, archangels and that great company of gnarly old saints, we believe that someday soon this whole dirty world will finally be filled with the knowledge of God’s glory. He will breathe once more into the dust of the earth. And on that day, every knee will bow. Every blaspheming tongue will cry, ‘Oh my God!’ Every hand will be raised in surrender. And he will choose the ones with dirt in the creases of their hands, just as he always did. Flesh will become Word, and dwell with him in glory.

Selah

Although the word selah occurs seventy-four times in the Hebrew Bible, no one really knows exactly what it means. Featuring mostly in the Psalms, it may have been a note to the choirmaster marking a change of verse, rhythm or melody. Selah probably meant ‘pause’.

But there’s more to it than that. Its Hebrew root seems to be the word calah, meaning ‘to hang’ or ‘to weigh’. Selah may also, therefore, have been a reminder to the worshippers to weigh the words they had just sung or heard.

At the end of every chapter of this book you will find an invitation to selah – to ‘pause’ and to ‘weigh’ the words you have just read. Not to rush ahead to the next chapter, but to stop and reflect. It’s a reminder to be still, so that this book about prayer can become your own living conversation with God.

PRESENCE

Encountering God

My Father’s house …

(John 2:16)

If your Presence does not go with us, do not send us up from here. How will anyone know that you are pleased with me and with your people unless you go with us? What else will distinguish me and your people from all the other people on the face of the earth? (Moses, Exodus 33:15–16)

2: The Time of Our Lives

Portugal ~ New York City ~ England

It is a strange glory,

the glory of this God.

(Dietrich Bonhoeffer)1

It was breakfast time in New York City and well past midnight in Tokyo. Throughout the Middle East the shadows were lengthening, offices closing, preparing for Maghrib – the evening call to prayer. On the cliffs of Cape St Vincent, that arid Portuguese headland where the Mediterranean and Atlantic oceans collide, it was 3.46 p.m. You probably remember where you were when it happened too.

There is a symmetry to life: the shape of a tree; the mirror image of a beautiful face; the cadence of a melody; the pattern of breathing, in and out; the tender way a mother cares for her daughter when she is little, and then the daughter cares for her mother when she is old; the daily constellation of coincidences attributed to luck, genetics, God or the stars.

In the symmetry of my own life, Cape St Vincent has become a Bethel, a fulcrum, the sort of unlikely location where you wake up blinking one day and say, ‘Surely the LORD is in this place, and I was not aware of it … How awesome is this place!’ (Gen. 28:16, 17). On my only previous visit, several years earlier, I had been a long-haired student, hitch-hiking around Europe with a friend. We were having the time of our lives, camping wild, cooking fish on open fires, drinking cheap red wine under the brightest stars you ever saw, relentlessly travelling west traversing the golden coves and rugged battlements of the Portuguese Algarve. Eventually the ocean on our left began to appear on the right as well. The land gradually tapered, rising steadily, becoming more desolate, until we found ourselves standing alone on the vast natural ramparts of Cape St Vincent. Laughing that we were to be the most south-westerly people in Europe for a night, we had pitched our tent and fallen asleep. But I had woken and climbed quietly out of the tent. Standing there on those cliffs, commanding the prow of a sleeping continent, I’d lifted my hands to pray, first for Africa to the south, then for America to the west, and finally, turning my back to the seas and staring at our little tent and the scrubland beyond, I’d begun to pray for Europe. And that was when I had witnessed the thing that would, I suppose, change the course of my life; the thing that had finally drawn me back here, after all these years, for this strange day of all the days there’d been.

Waves of electrical power had begun pulsing through my body and I’d found myself looking out at an army, a multitude as far as the eye could see. Thousands of ghostly young people seemed to be rising up out of a vast map superimposed – like a scene from Lord of the Rings – on the physical landscape. There was an eerie hush, a sense of expectancy, as if they were preparing for something por...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Epigraph

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introductory Letter from Pete

- Foreword by Bear Grylls

- Introduction

- 1: Punk Messiah

- Presence – Encountering God: ‘My Father’s house …’

- Prayer – God’s Presence in Power: ‘… will be called a house of prayer …’

- Mission – God’s Presence in the Culture: ‘… for all nations …’

- Justice – God’s Presence in the Poor: ‘… but you have made it “a den of robbers”.’

- Joy – God’s Presence in Us: ‘I will … give them joy in my house of prayer.’

- Study Guide: For small groups and further reflection, by Hannah Heather

- Disclaimer: Miracles

- A Note to My American Friends (with Glossary)

- Notes

- Index of Bible References

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Praise for Dirty Glory

- Copyright