- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

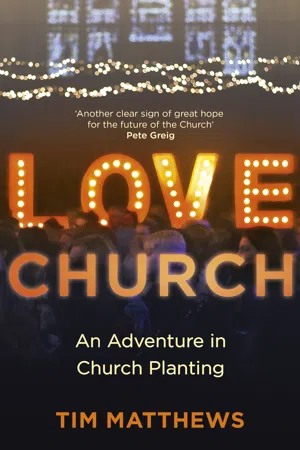

This book tells the story of the process of moving to Bournemouth to set up a new church from scratch, on the back of numerous similar failed attempts in London, and the bumpy and scary journey to success St Swithun's has travelled since. Tim demonstrates, through his story, how he has pushed through failure and disappointment with tenacity to trust in God and his plan and timing - and how hundreds of people are discovering faith in Jesus Christ as a result.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Love Church by Tim Matthews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Every day is a school day

Start children off on the way they should go, and even when they are old they will not turn from it.

Proverbs 22:6

I was raised in a loving, stable family home in the leafy middle-class town of Guildford. I went to decent schools. I had some fun friends and didn’t hang out with the wrong crowd. I enjoyed church youth groups. I was fit and healthy and played a lot of sports. I was reasonably intelligent, although by no means outstanding. I did okay at GCSE and A-level without too much crisis. But at the end of my time at school I felt restless and hungry for a change of scene and decided to take a year out before heading off to university. I was in a group of friends who used to head down to England’s south coast – Devon, Cornwall or even west Wales – to surf during the weekends and school holidays. One of them spotted a small advert in the back pages of Surfer magazine and dared me to apply. It was to go to Mexico for a year with a missions agency called Surfers For Missions International (SFMI).

The SFMI programme turned out to be a six-month Discipleship Training School (DTS) run by Youth With A Mission (YWAM). I decided to go for it and wrote to several family friends asking for their help to finance the trip. Thanks to their generosity, at the end of a gloriously long summer in England and having said goodbye to school, I found myself on a plane to Mexico. I was looking forward to the surfing but not a little intimidated by the idea of what I might find. I’ve surfed ever since I was a teenager and was used to the slow, freezing cold waves on England’s south coast, with the odd occasional trip to bigger breaks elsewhere. Mexico was very different though. Pretty much the first thing I did when I arrived at the SFMI house in Mazatlan was to go for a surf. Wherever we were in Mexico for the next six months we’d surf at least once a day, or more if we could. My first surprise was that the water was bath-warm, particularly when a late-afternoon tide came back in over the sun-scorched sand. Surfing in board shorts only was a far cry from the heavy, thick wetsuits used in the UK. And then there was the size, speed and ferocity of the waves. More than once I just about managed to paddle out on a rip into big surf that was way beyond my skill level. It’s a terrifying feeling knowing that the only way to get back to the beach is to pick just the right wave, take a very deep breath, turn and paddle like your life depends on it, then ride a monster wave that will chew you up with utter disdain for your well-being. Pretty scary. And incredibly thrilling.

Hazards abounded: burning sun, vicious rip-currents, shallow rocks, reefs and all manner of animal life in the ocean could all turn a fun surf session into a world of pain very quickly. One afternoon I duck-dived under an innocuous wave and surfaced into the tentacles of a blue-bottle jellyfish. The stings seared right across my diaphragm and I began to have trouble breathing. (Apparently, I should have asked one of my friends to pee on me but neither I nor the guys knew of that particular trick!). My friends wisely took me to a Red Cross clinic, where, after fainting in the shower, I was given some kind of injection, although to this day I have no idea what it was. What I do know is that I had painful chemical burns all down my torso for weeks afterwards.

Despite missing out on the questionable experience of being peed upon, every day in Mexico contained an adventure. And it was the same in my faith. From the safe shallows of middle-class English Christianity, I found myself surrounded by people who were totally sold-out for God. We’d simply rock up at a coastal village, surf the beach, and start evangelising anyone we met. We’d play beach football or baseball, sing songs and perform puppet shows to draw a crowd, then share our testimony and ask for a response right there and then, praying with anyone who wanted to commit their lives to Christ. There are valid questions about the long-term effectiveness of such an approach, but we were young and cared little for anything other than what we believed God was asking us to do each day as it came to us. In hindsight, I see that I had become a little spiritually intense. But I was impressed with the authentic and courageous evangelists I travelled with and wanted to emulate them; they seemed to exhibit so little of the timidity and British reserve that had stymied my own attempts at sharing my faith up to that point in my life.

Somewhere near the coast of Southern Mexico between Puerto Escondido and Puerto Vallarta I met a boy, aged about twelve, who lived in a large orphanage run by Catholic nuns. There was something about this kid – he was just so happy. We spent several days playing games and a lot of football. We bonded. He was always great fun, did his chores and studied hard at school. He liked helping the other kids, he loved singing and prayed earnestly and beautifully during the nuns’ simple chapel services. Everyone called him Chico.

On one occasion, I was talking to the sisters who ran the orphanage and they told me Chico’s story. He had lived with his family in a remote village in the interior jungle in Southern Mexico. His father was a violent man and an alcoholic. One day, when Chico was at home with his mother, his father came home very drunk and started to beat his mother, as he had done many, many times before. As was his way, Chico hid under the kitchen table. This beating was different, though, and went on and on and on. Tragically, he saw his father beat his mother to death, right in front of him.

As his father continued to beat his dying wife, Chico’s older brother returned home. Seeing what his father had done, the brother grabbed a kitchen knife and killed his father, there in front of Chico, still hiding under the table. Men from the local village, hearing his brother’s howls of rage, ran to the house, whereupon seeing the older brother standing over the bodies of his mother and father, knife in hand and howling in rage, they shot him on the spot.

The villagers eventually discovered Chico hidden under the kitchen table, locked in silent fear, and took him to the Catholic orphanage. The sisters wept as they told me Chico’s story, explaining that for the first few years at the orphanage he hadn’t uttered a single sound, so traumatised was he. Yet as I listened, I simply could not reconcile the joy-filled boy I had encountered with the tragic tale they told. I couldn’t help asking them, ‘I don’t understand. How can Chico be so joyful and caring now?’ They replied, ‘Jesus has done this. Jesus is everything to Chico. Chico’s life is a miracle.’

After six months in Mexico the DTS was complete and God had changed me. My Christian faith was no longer a theory but a very real relationship with God. I was a braver evangelist (and a much better surfer). On one of my final days I took a bus ride into town and treated myself to a coke in the ice-cold air conditioning of McDonalds. I sat in the corner, journalling, reflecting on all that God had allowed me to be part of, and wondered what might be next. As I prayed, I sensed God saying that he wanted me to lead an evangelistic trip to the North of England and I simply agreed with God that I would do it. A few days later, rocking the surf-bum look, with a good tan, crazy blonde afro hair and two surfboards wrapped in Mexican blankets, I came home. From the heat and intensity of Mexico, I landed into a cold, drizzly day in London. I didn’t want to lose what I’d found, so in the days and weeks that followed I called my friends, wrote to a church I knew in Ambleside, and two months later led a small team to the Lake District.

I was eighteen and didn’t have the first clue about how to lead a team on a mission trip. I thought I needed a few badges of office to make it clear who was boss, so I borrowed my Dad’s old briefcase to keep stuff in. I thought God would only move through us in direct proportion to our purity, effort and obedience, so I demanded that we drank no alcohol and travelled not a single mile per hour over the speed limit. I look back now and cringe, having made all the girls sleep in a tent outside as I didn’t think the boys and girls should be in the same church hall we’d been told we could have as our base. The tent blew down on the second night during a thunder storm and I only just let the two groups set up camp inside, sleeping at opposite ends of the hall. I’d also never given a sermon and was horrified when the church asked me to preach on the middle Sunday, stammering my way through a horrific mess of a message. At the time, the church was thinking of planting to a coastal town called Whitehaven. We’d been there to pray and seen that the proposed site was opposite a multi-storey pay-and-display car park. My mind-blowingly profound and contextual instruction to the church was that they should ‘pray and display’. I remember the whole church laughing at me, shaking their heads at my ridiculous, contrived and cheesy message. Despite all this, amazingly, some people did come to faith on that trip and God began something in me too.

Being young and zealous, I’d begun to develop a kind of intensity that might have looked spiritual but beneath the surface was a simple blindness to my weaknesses. God would have to reveal those to me if I was to grow as a disciple and accomplish anything of significance with him in my life. Self-awareness and emotional maturity are such huge factors in spiritual maturity. But I knew none of that back then. As I was to find out, intensity is not a gift of the Holy Spirit.

When I returned home I was naturally excited to see my girlfriend with whom I’d exchanged countless letters while I’d been away. She came round the day after I got home, promptly bursting into tears as she told me she had cheated on me while I was away. I couldn’t reconcile the love she’d declared in her many letters with what she was telling me, even though she was truly sorry and, to be fair to her, hadn’t tried to hide anything. I felt hurt but oddly numb. I didn’t take the time to consider what I thought or felt about it; I simply ended it right there and then. I discarded her in a way that must have been wounding and now regret the way I reacted.

In the months that followed I went to university in South Wales. It seemed to rain every single day of my first term. Despite some good people and enjoyable times, on the inside I was becoming more miserable. I didn’t really stop to think what I was doing when I met a girl who didn’t share my faith at all. Her demeanour and lifestyle seemed to offer an intoxicating thrill. We hit it off and it all got serious very quickly. Deep down I knew she was the wrong girl for me but it was like an addiction I couldn’t – maybe wouldn’t – control. Our relationship thoroughly messed me up; she had another rich boyfriend who would turn up unannounced to whisk her off on luxurious trips, needless to say without me. Her own father had done much the same thing to her mother. They say hurt people, hurt people; and so it turned out. I loved her so I always took her back, not blaming her because I was complicit in this messed-up thing. I blamed myself. It took me years to forgive myself for that relationship, long after God had forgiven me.

Our relationship came apart at the seams when we were both on a European year in the middle of our studies: she was in Italy and I was in Spain. I was crushed by the emotional turmoil of losing her and choked with all the guilt and anger that our relationship had left me with. I was on my own and I had no money. I was thrown out of the shared flat of foreign students where I had a small room, and for a while I was at the mercy of loose friendships, sofa-surfing in a few different flats, teetering on the edge of rough sleeping. But in the naivety of my youth I didn’t see it. I had an old, cheap guitar with me and I could play three chords, so I decided to start street busking to get money. The trouble was, I was absolutely terrible at it. I recall regularly setting up to busk opposite one particularly posh jewellery shop. I did so only because I knew the store manager would always come out and pay me to go and play somewhere else because I was scaring his customers away. When I look back on those times now, I’m aware how low my self-esteem had got; at the time I welcomed the rejection because it validated what I felt about myself. It was the lowest point in my life.

Weirdly, however, I remember those six painful, impoverished months on my own in Spain with a huge amount of gratitude. They were the making of me. All I had was God and I threw myself at him. I read in the psalms that ‘The Lord is close to the broken-hearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit’ (Psalm 34:18). That became no longer just a verse to me, or something I believed was true; it became something I experienced. For the first time in my life, my relationship with God stopped being something I could turn on and off. God became like the air I breathed. I didn’t just want God for comfort, I needed God for survival and, in my angst-ridden, rather melodramatic way, would echo King David’s prayer: ‘From the ends of the earth I call to you, I call as my heart grows faint; lead me to the rock higher than I’ (Psalm 61:2).

In The Purpose Driven Life, Rick Warren writes: ‘You will never know that God is all you need until God is all you’ve got.’1 My need for God wasn’t heroic and it wasn’t a considered decision reflecting mature spiritual discipline and knowledge. Quite the opposite: God was all I had. If I didn’t talk to him, I didn’t talk to anyone. If he didn’t give me money, I didn’t have any money. If I couldn’t find hope or joy in him, I couldn’t find it anywhere else. But in reaching the end of myself, I’d found the start of something that changed the rest of my life. In the words of the great Richard Rohr, I found myself ‘falling upward’.2

The Apostle Paul knew all about falling upward. He believed that the Lord had deliberately weakened him, using the devil to do so. We recoil at the idea, finding it almost impossible to imagine why God would do such a thing. In the strengths-based culture of our times, choosing weakness as a strategy to progress is wholly counter-intuitive. Yet Paul wrote: ‘In order to keep me from becoming conceited, I was given a thorn in my flesh, a messenger from Satan, to torment me. Three times I pleaded with the Lord to take it away from me. But he said to me “my grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness”’ (2 Cor. 12:7–10). This realisation had such a profound effect on Paul that he concluded, ‘When I am weak, then I am strong’ (verse 10). God was helping me learn to rely on him alone rather than what I imagined to be my own ability.

Not that I knew it at the time – it took a good few years back in the UK to figure it all out. Having made a complete mess of the first two years of my time at university, I returned with a new focus to make it worthwhile. I discovered that inner motivations to achieve things are far stronger than outer ones. Success has to mean something personally to me before I get seriously interested in pursuing it. My first two years at university hadn’t meant much to me personally, but when I returned I wanted to get a good degree and studied accordingly. The final year went so well that one of the professors who taught on the course hauled me into his office and demanded to know why I hadn’t applied for his PhD programme. I was gob-smacked as I’d never even considered it. The professor arranged a scholarship and so I carried on my studies, also working as a researcher and tutor. Within three years, I’d completed a doctorate in marketing and social psychology. Although I enjoyed the study and loved the teaching opportunities, I’d ended up in an academic research group that seemed more driven by ego and selfish ambition than by the worthy pursuit of academic goals. The part of my research that I’d enjoyed the most was spending time with business owners and managers, trying to understand their world and add value to them. So I changed track and began training as a chartered accountant.

My personal faith grew throughout that time and so did my involvement with church. I tried different congregations in various denominations ending up with a tight-knit group of Christians who met together as a community church, part of the Pioneer network. They loved me back to life. They tried to live without any disconnect in their faith between Sunday worship and normal life and that was tremendously refreshing. When I’d been studying for my PhD, I’d started playing five-a-side football with some of the other tutors and researchers. One night I fell against a wall and split my head open. I recall being notably struck during and afterwards that no one really seemed to care; certainly no one helped me. I drove myself to the hospital with blood gushing down my face. Playing football with the guys from the community church was a completely different experience; there was far more banter and laughter – honesty too and a willingness to confront one another when people stepped out of line.

Throughout my late teens and twenties I’d been involved in leading summer and Easter Christian camps for kids and teenagers. I’ve always loved outdoor adventure and water sports so it was a natural thing for me. One camp was called Sail and Surf where we’d teach fifty or so teenagers to sail and windsurf in the shifting, fickle winds of Lake Windermere in the Lake District. We tended to get either a howling gale and rain, or not a breath of wind and hot sunshine. I always preferred the windy days because that’s what we were there for. But the becalmed, sunny days taught me much more about leadership; it was on those days that you had to inject some fun into proceedings. I had to be the first to don a cold, clammy wetsuit and the first into the water for the raft-building challenge or whatever other ‘no wind’ activity we’d lined up for that day. Periods of calm that stretched on for days also taught me to pray. The centre where we were based had a long jetty that jutted out into the water. Early in the morning before anyone else was up, I’d go and stand at the end and pray for wind and keep praying until I sensed some kind of breakthrough. It was amazing to me how often those prayers about the weather were answered. That said, I’ve been to plenty of Christian camps and events where our prayers for perfect conditions seem to have been ignored. More often than not, though, I’ve reflected back on how adverse conditions bring people together, so maybe it’s not so bad.

The camps taught me too that miracles weren’t just reserved for YWAMers in Mexico. One summer a fifteen-year-old girl called Kim came on Sail and Surf together with her friend Sarah. Kim’s grandmother had paid for them to go, a faith-filled Christian woman who had neglected to tell the girls that she was sending them to a Christian camp. Five minutes after arriving onsite off the coach, Kim found me and explained that there had been a bad mistake: she’d opened her bag to find a Bible that her grandmother had smuggled in when she wasn’t looking. Then she’d seen on the programme that each evening we’d have a meeting where we’d sing worship songs and hear a short talk based on a Bible passage. Her immediate family were not Christian and she couldn’t imagine anything worse. I tried to set her mind at ease, but she didn’t want to listen. In the end I agreed to take them to the station the next day to catch a train home, but during the night the whole team prayed and in the morning the girls agreed to stay just for the day’s sailing, then travel home after supper. They had such a fantastic time that they confessed they could probably bear the evening meetings as the first one actually hadn’t been as bad as they’d feared; in any case, it was worth it for the sailing during the day. They began to make friends with some of the other girls and we didn’t hear any more talk about going home.

On the fifth morning Kim asked to speak to me later on. She intrigued me by saying that she knew she had to talk but didn’t feel ready, and wanted to enjoy the day fully first. That evening she explained just why she’d been so resistant to the Christian bit of the holiday: her father had died horribly when she was younger, and she’d written in her diary: ‘If I ever find out that God exists and I meet him, I’m going to tell him to his face how horrible he is for taking Daddy away. I’m going to tell God that I hate him.’

I didn’t know what to say and started to mumble some words to express how awful that must have been for her. Kim wasn’t interested in my sympathy and signalled for me to stop talking. She looked at me and said:

Here’s the thing, though – last night I had a dream. I was lying in my bed when the door opened and in walked Jesus, who sat at the foot of my bed. I wasn’t scared. I was furious. I tried to tell him how much...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: 570,000 reasons to get out of bed

- 1. Every day is a school day

- 2. The reluctant leader

- 3. Repurposed for hope

- 4. The ones that got away

- 5. Your Macedonian moment

- 6. My big but

- 7. No turning back

- 8. It’s snowing money

- 9. Budget for coffee

- 10. Relational intelligence

- 11. Worship like you mean it

- 12. Battleship, not cruise ship

- 13. Finding freedom

- 14. How to lose £0.5m in thirty seconds

- 15. Unblock the flow

- 16. Get risky, stay risky

- 17. Transition times

- 18. Second site

- Epilogue: Live again

- Notes

- Acknowledgements