![]()

1

The Rise of Professional Arboriculture

Since trees were first planted and cultivated in Britain’s towns and cities, somebody has had to undertake this work. Those employed professionally on tree work have generally required a level of specialist knowledge, not least because of the risks involved in maintaining or removing mature trees in close proximity to people and built development. If that was not the case then this difficult and demanding work could be a particularly dangerous occupation, as many amateur tree workers down the years have found out to their cost.

Over the centuries, the planting and care of urban trees has been embraced by a range of different professionals (Figure 1). This has included horticulturists, landscapers, foresters, civil engineers and many others. Since the early twentieth century, the planting and care of trees for amenity purposes has come to be regarded as the province of arboriculture, although the original use of that term was almost synonymous with forestry (James 1982, 122). Modern arboriculture as a science and profession can trace much of its origins to both horticulture and forestry. Its approach to the planting and cultivation of trees is derived largely from horticulture. However, much of the equipment and techniques involved in mature tree maintenance have their origins in forestry.

FIGURE 1. Over the centuries various professionals have been engaged in the planting and care of trees, in both urban and rural situations. This woodcut of tree workers is from the title page of the 1656 edition of William Lawson’s A New Orchard and Garden.

While the recognised scope of arboriculture focuses principally on trees, it can also embrace other woody plants (Wilson 2013, 9). Its emphasis has traditionally been on the so-called amenity benefits of trees, with much attention given to the aesthetic. Arboriculture generally focuses on individual or small groups of trees, in both urban and rural situations. Since the 1960s, the planning and management of tree populations throughout an urban area has become known as ‘urban forestry’ and the totality of trees and woodland in and around a town or city is now referred to as the ‘urban forest’ (Johnston 1996). In historical terms that is a very recent development.

This chapter explores the development of arboriculture as a professional activity concerned with the planting and care of amenity trees in urban areas. Some difficulties were encountered in the research process because of the historical changes in the meaning of the term ‘arboriculture’. What might be described as arboriculture in many eighteenth century texts is now regarded as forestry and beyond the scope of this book. Furthermore, in dealing with the topic of professionalism in arboriculture it has been difficult to make any precise distinction between what is rural and what is urban. Therefore, in this chapter more than any other, we tend to cover more general aspects of arboriculture.

Early arboricultural practices

Perhaps the earliest arboricultural practices in Britain can be traced back to the Romans. They took some of the principles and practice of tree planting and care established by the Greeks and other early civilisations and adapted them to their own needs (Campana 1999, 6). Their achievements in general landscaping often exceeded anything seen before and provided a basic framework of tree culture, style and design that would survive the demise of the ancient world in Europe to emerge again in the Renaissance. The Romans were the first to give the tree worker a name: arborator. Used originally only for a tree pruner, mainly for fruit trees, it was later used to include all those who undertook planting and care with any trees. The name ‘arborator’ was still being used in this context by John Evelyn in the seventeenth century, although he more commonly used the term ‘arborist’ (Evelyn 1664, 75).

Following the end of the Roman occupation in the year 410, little progress seems to have been made in the theory and practice of arboriculture in Britain until the English Renaissance in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (Hadfield 1967). During this period the development of arboriculture was characterised by a focus on a formal style of landscaping, the establishment of early botanical gardens and early forest management. The fashion for a formal approach to landscaping in the gardens of country estates and town residences, heavily influenced by continental European styles such as the Italian, French and Dutch, emphasised a desire to control and manipulate nature. This was reflected in the pruning and landscape use of trees where topiary was fashionable and there was a preference for ordered and symmetrical arrangements of trees. While the economic value of trees was still of primary interest in Britain, the aesthetic considerations of trees and woodlands were also receiving more attention. The landscape itself, both rural and urban, contained a significant mix of native and exotic tree species. This reflected the considerable numbers of trees introduced from overseas and planted out in a variety of landscapes for their economic and aesthetic benefit (Loudon 1838a).

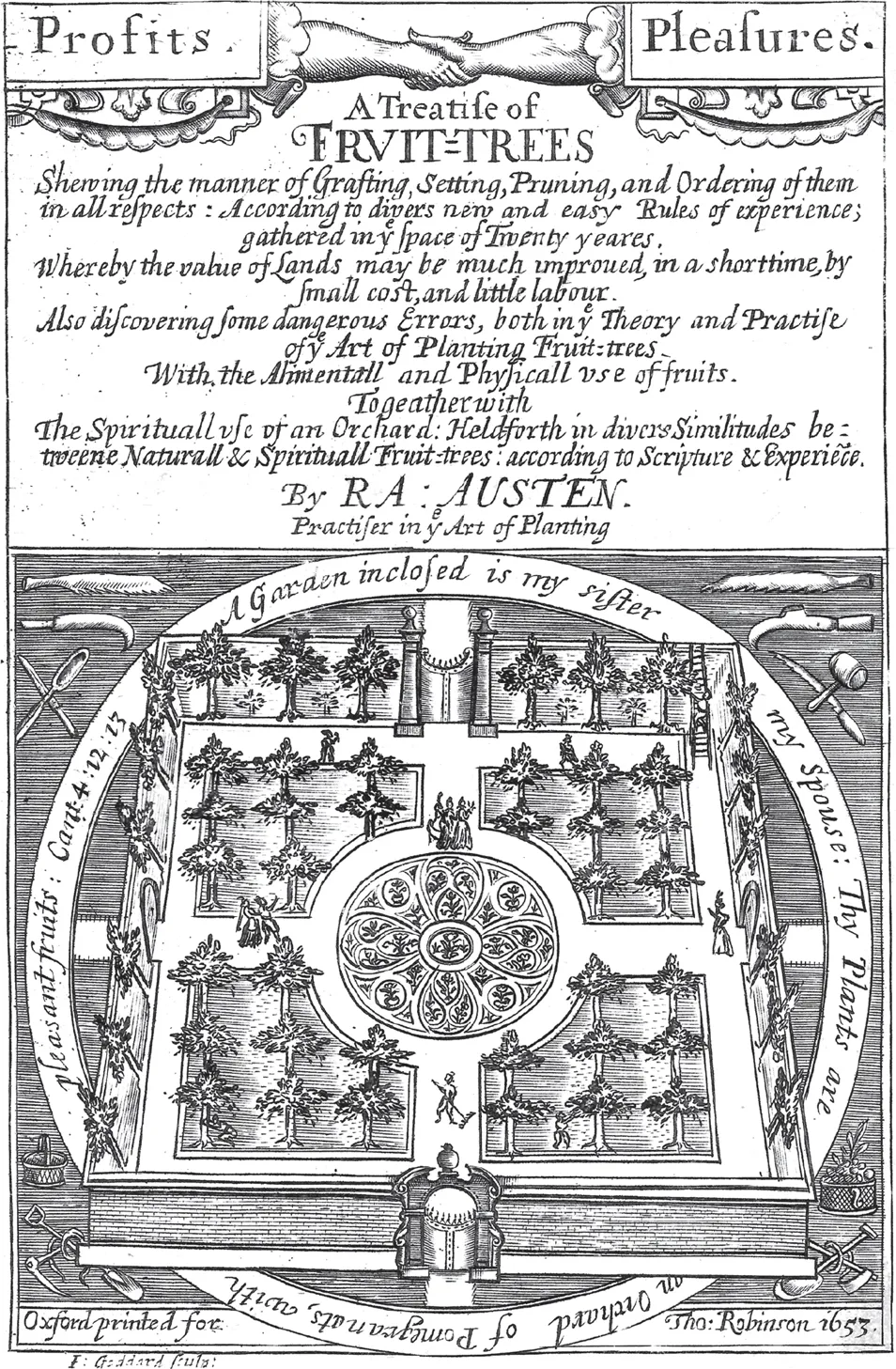

Scholarly works relevant to trees were also being published as scientific knowledge continued to expand. Early in the seventeenth century the previously allied subjects of horticulture and botany, both particularly relevant to trees, began to split into separate fields of study (Campbell-Culver 2006, 17). During this period and for some time after, much of the British literature on trees reflected economic preoccupations and tended to focus on forest (timber) trees and fruit trees. Nevertheless, these usually contained important information about basic arboricultural practices such as planting and pruning. In disseminating information on tree care practices among the landed aristocracy, a number of publications were influential. The earliest British reference book of note was probably The Book of Husbandry by Anthony Fitzherbert in 1534, which included some aspects of arboriculture, although only in a rural context (Fitzherbert 1882). In 1563, Thomas Hill wrote the first English book on general gardening, The Profitable Arte of Gardening, and this included some references to trees (Henrey 1975, 57). Hill followed this in 1577 with a more extensive work entitled The Gardener’s Labyrinth (Hill 1987). Leonard Mascall’s A Booke of the Arte and Maner Howe to Plant and Graffe all sortes of Trees, first published in 1569, gave considerable detail on the techniques of planting and grafting for fruit trees, including information on the equipment used (Mascall 1569). This was not actually an original text as it was based on a translation of a French work by Davy Brossard (Henrey 1975, 63). By contrast, William Lawson’s book A New Orchard and Garden, published in 1618, was based on the author’s forty-eight years of experience in a northern garden (Lawson 1618). It included the first detailed account of general arboricultural practices of that era, including tree planting, moving, pruning, wound treatment and cavity filling. He was also one of the first writers to recognise that most absorbing roots were close to the soil surface. Ralph Austen’s book A Treatise of Fruit-trees, published in 1653, ensured his reputation as one the most significant seventeenth century authorities on that subject (Austen 1653; Amherst 1896, 185) (Figure 2). Austen was also concerned with wider aspects of arboricultural knowledge with important contributions on the propagation, planting and care of trees.

Botanic Gardens began to be established in Britain from the seventeenth century, prompted in part by the steady introduction of new trees and shrubs (Loudon 1838a) (see Chapter 7). The oldest of these was the Oxford Botanic Garden (1621), followed by Edinburgh (1670) and Chelsea Physic Garden (1673). In his Arboretum Britannicum in 1838, John Claudius Loudon detailed the most important of these seventeenth century gardens and the trees and shrubs that were introduced during that time (Loudon 1838a). As the flow of new tree introductions continued, these began to be recorded in learned books on the subject. The first fully illustrated encyclopaedia of trees to be published in Britain is likely to have been Dendrographias, sive historiae naturalis de arboribus et fructicibus (Johnson 2010, 48). This was written by John Johnston (Johannes Jonstonus) and published in Frankfurt in 1662. Had this remarkable work not been written entirely in Latin, it would have been more widely known in later years.

FIGURE 2. Ralph Austen’s A Treatise of Fruit Trees in 1653 was not only a major work on pomology but also included general information relevant to practical arboriculture. However, its preoccupation with moral and religious matters probably limited its popular appeal. The title-page engraving is by John Goddard.

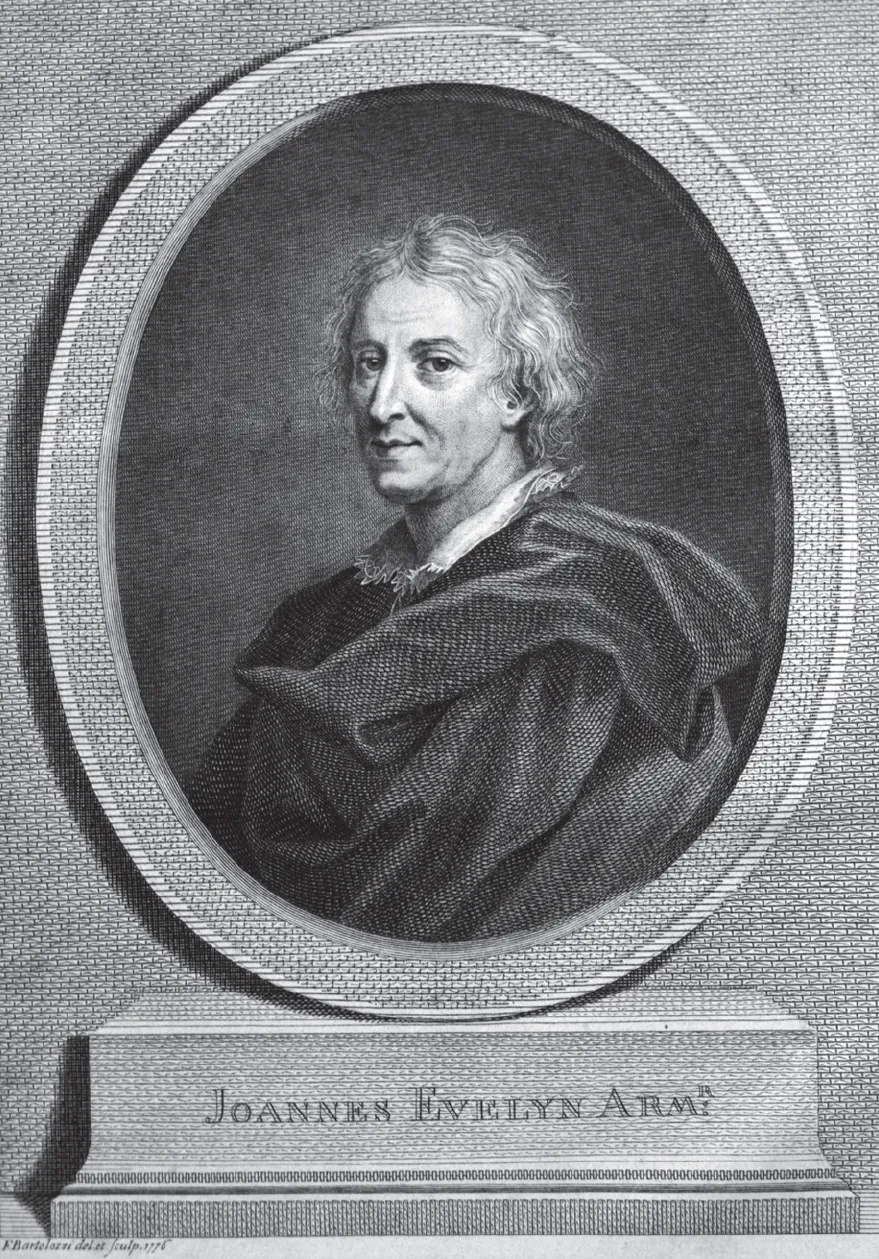

John Evelyn’s Sylva or a Discourse of Forest Trees, first published in 1664, is regarded by some authorities as one of the world’s greatest books on trees in any language (Campbell-Culver 2006, 46) (Figure 3). Sylva is also widely recognised as the first text on forestry published in English that was also a passionate call to plant and restore woodlands for the nation’s economic survival. Despite its title, it is not just about ‘forest’ or timber trees. Evelyn went beyond his original brief from the Royal Society and included the use of trees in gardens with a number of species of ornamental value (Evelyn 1664). While there is almost no mention of trees in towns, Evelyn’s work is a remarkable source of information about early arboriculture. He was critical of tree work standards at that time and had this to say on the subject of poor pruning:

For ’tis a misery to see how our fairest trees are defaced and mangled by unskilful Wood-men, and mischievous Bordurers, who go always armed with short Hand-bills, hacking and chopping off all that comes in their way; by which our trees are made full of knots, boils, cankers and deformed bunches, to tlu-ir utter destruction.

Evelyn adds that good workmen should be ashamed of this unsatisfactory situation. He goes on:

As much to be reprehended are those who either begin this work at unseasonable times, or so maim the poor branches, that either out of laziness or lack of skill, they leave most of them stubs, and instead of cutting the arms and branches close to the bole, hack them off a foot or two from the body of the tree, by which they become hollow and rotten.

Evelyn 1664, 74

FIGURE 3. John Evelyn (1620–1706) was the author of Sylva or a Discourse of Forest Trees, regarded by many as the one of the world’s greatest books on trees. This portrait of Evelyn was engraved by Francesco Bartolozzi and is from Hunter’s 1776 edition.

According to Evelyn, pruning should be undertaken “…by cutting clean, smooth and close, making the stroke upwards and with a sharp bill…” to avoid the bark and branch tearing. His Sylva went through many further editions both in his lifetime and subsequently. Later editions included more information on arboricultural practices, including further descriptions and diagrams of tools and equipment required for the work. Sylva, or Silva as it was spelt in later editions, remained an authoritative work on trees and tree culture well into the eighteenth century.

In 1776, seventy years after Evelyn’s death, a new edition of Sylva was published with extensive notes by Dr Alexander Hunter of York (Evelyn 1776). Hunter’s edition revived the national ardour for tree planting that the first edition created (Henrey 1975, 110). It also came at a time when it was increasingly popular to use trees in a general plan for the embellishment of estates and so was purchased enthusiastically by landowners. Collectively, all the editions of Sylva have ensured that no other work on arboriculture written before 1800 exerted a greater influence on forestry in Britain. For many generations of arboriculturists and foresters, the first edition remains the most iconic British work ever written on trees. Others have been more critical of this early text and regard Hunter’s edition with his own notes as more valuable (James 1981, 131).

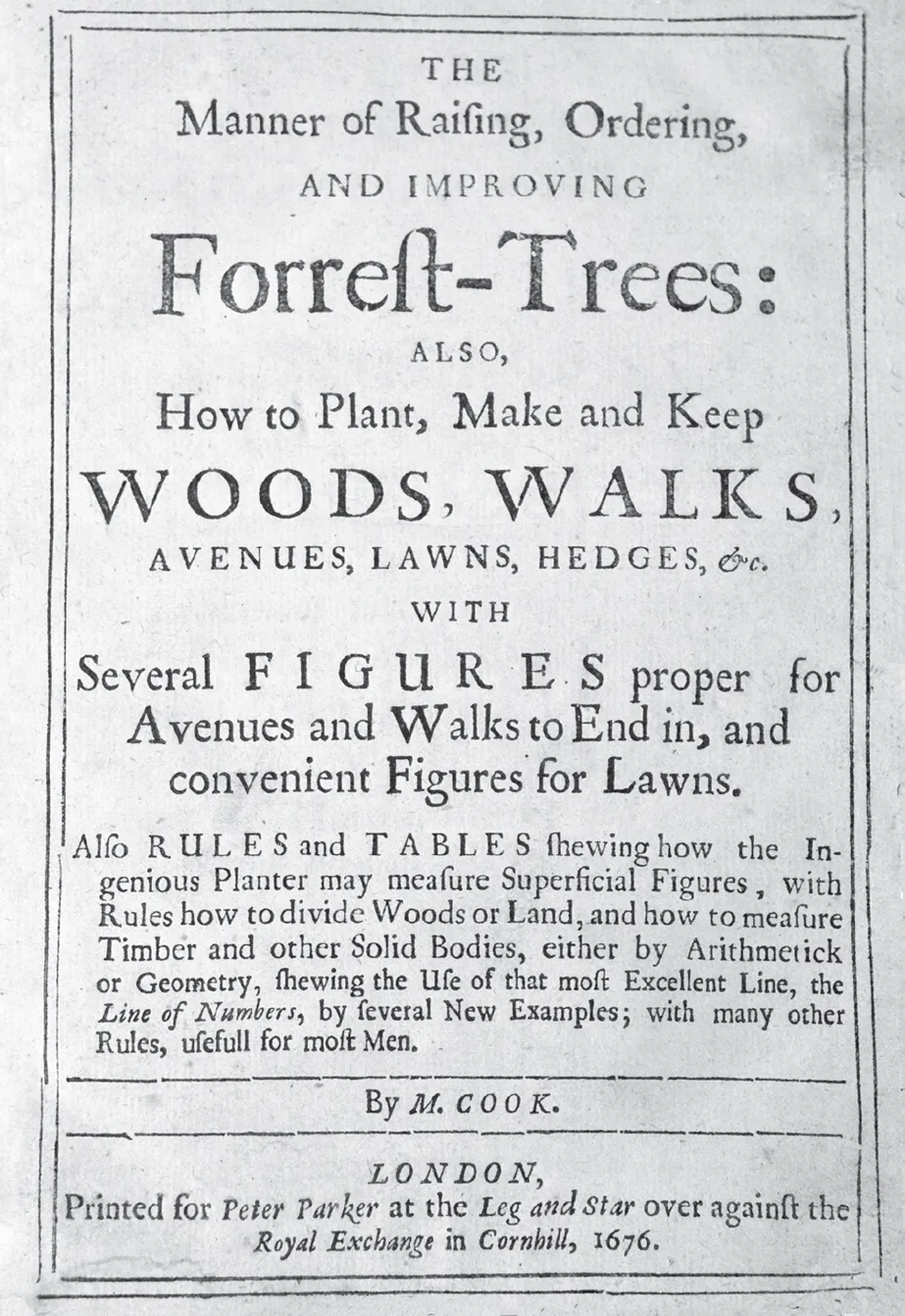

A contemporary of Evelyn was Moses Cook, partner in the Brompton Park Nursery and gardener to the Earl of Essex (Hadfield et al. 1980, 79). He wrote The Manner of Raising, Ordering, and Improving Forest-Trees, etc., published in 1676, which proved to be highly influential (Cook 1676). Not only did Cook explode some popular myths about tree cultivation but he also set out some basic principles of good arboricultural practice, particularly in relation to the use of trees in walks and avenues. Cook was well known to Evelyn and is often credited as being the source for the practical horticultural detail in Evelyn’s works (University of Toronto 2012) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. In 1676, Moses Cook published his remarkable work The Manner of Raising, Ordering, and Improving Forest Trees. This has been largely overshadowed by Evelyn’s Sylva but some authorities credit Cook as being the source of the practical horticultural detail in Evelyn’s works.

The most influential British garden designers of this period were George London and Henry Wise, whose services were in great demand by the aristocracy and landed classes (Quest-Ritson 2001, 83). Much influenced by the French formal style of André Le Nôtre (1613–1700), their garden designs represented the epitome of taste and they dominated the horticultural scene for nearly fifty years. London and Wise were originally in partnership as nurserymen at the celebrated Brompton Park Nursery in Kensington, London, where Moses Cook had been a partner. Brompton Park specialised in ornamental trees and shrubs and eventually covered 100 acres, making it by far the largest nursery in England. It was the first commercial tree and shrub nursery to achieve such a dominant position in the English nursery trade, in much the same way as Veitch of Exeter in the nineteenth century and Hillier of Winchester in the twentieth.

Arboriculture in the 1700s

By the early eighteenth century, the British landed gentry and aristocracy were reacting against the formal garden style that was largely French-influenced. The popularity of these landscapes with their parterres, long radiating avenues of trees, and straight-edged canals was fading. Now, a more simple and natural approach was gaining favour that involved the extensive planting of trees as part of the...