- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Fatality quotas implemented in China's industrial section and local governments are being used to promote work safety and therefore, reducing the number of work-related deaths. Given the controversial nature of this policy, Gao analyzes how the fatality quotas are functioning to aid the country in balancing economic growth and social stability. The book also examines significant implications caused of this policy's implementation in the local regions, and reveals how local officials attempt to handle these problems.

This is the first book to systematically examine the role of death indicators in work safety improvement in contemporary China, revealing insight into Beijing's quota-oriented approach to policy-making.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Work Safety Regulation in China by Jie Gao in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

DOI: 10.4324/9781315646459-1

China’s socioeconomic transformation since the late 1970s has brought a new generation of governance challenges for national leaders. Many of these issues, such as pervasive corruption in both the public and private sector, soaring housing prices, frequent food safety scandals, environmental deterioration, rising social tensions, and the like, were not prominent at all in Mao’s time. Although tackling the roots of some of these challenges may demand substantial reform to the political system, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders have not been keen in making profound changes to China’s authoritarian political system. Instead, they rely on a variety of policy innovations and administrative means to fix politically pressing issues—an approach that paramount leader Deng Xiaoping described as “crossing the river by groping for stones” and that other critiques describe as short-term quick fixes to systematic political problems (Pei, 2006). Will the CCP’s regime be able to survive economic liberalization and improve its resilience and legitimacy? Or will it be trapped in the middle of the river and eventually decay or collapse, as has happened in many other authoritarian countries? This is a central debate in China studies in the past two decades (Cai, 2008; Heilmann and Perry, 2011; Hess, 2013; Li, 2012; Nathan, 2003; Pei, 2012; Schubert, 2008; Shambaugh, 2008; Sheng, 2009; Tsai and Kou, 2015; Tsang, 2009; Yan, 2011).

One of the most prominent governance challenges during China’s economic transition is the maintenance and improvement of workers’ occupational safety and health (OSH). After all, according to the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), “In building socialism, it is essential to reply on workers, peasants and intellectuals and to unite all forces that can be united” (National People’s Congress, 2004). Yet, as in many other transitional societies, China’s impressive economic growth has come at a heavy social cost (Yu, 2006). According to official statistics, work-related fatalities increased steadily during the 1990s and apparently peaked in the early 2000s—a period when China’s GDP (gross domestic product) was experiencing continuous double-digit growth. In 2003, China recorded a total of 136,340 work-related deaths in 963,976 industrial accidents, which was a 26 percent increase from the 108,205 deaths recorded in 1998 (Bureau of Work Safety of the State Economic and Trade Commission, 2000; State Administration of Work Safety, 2004). China’s coal industry accounts for 33 percent of the world’s total coal production, but 79 percent of the world’s mining casualties (Li, 2005, p.19). In terms of deaths per million tons of coal produced, in the early 2000s, China’s fatality rate in coal mine accidents was about 10 times of that of Russia, 12 times of that of India, 30 times that of South Africa, and 100 times that of the United States (Huang, 2004, p.3). A report of the International Labour Organization (ILO)1 showed that in 2003, China’s work-related death toll (460,260) exceeded that in the established market economies (297,534), formerly socialist economies (166,265), India (310,067), other Asia and Islands (246,720), sub-Saharan Africa (257,738), Latin America and the Caribbean (137,789), and the Middle Eastern Crescent (125,641) (International Labour Organization, 2003, p.7). Put in this light, in the 1990s–2000s, China appears to have been the deadliest country on the globe in which to work.

How to improve workplace safety and reduce work-related fatalities have thus been crucial questions for several generations of the CCP leaders. Since 1979, the central leaders have repeatedly stressed the importance of taking work safety seriously. For them, the terrible work safety situation, especially the frequent occurrence of serious accidents that cause the loss of many lives at once, has important political implications. On top of everything else, it jeopardizes social stability, the basis and precondition for China’s reform and development. As Zhang Jinfu, the first director of China’s National Work Safety Commission (NWSC) (which was established in 1985), emphasized, “The serious work safety situation is not only an economic problem, but more importantly, a political one” (Zhang, 1985, p.16).

The concern about political instability is absolutely legitimate. China’s first labor-focused nongovernmental organization (NGO) was established to address unsafe practices in workplaces in Guangdong Province following a horrific 1993 fire in a toy factory that caused 87 deaths (Chan, 2013). Economic reform and transition have made Chinese workers more conscious of their rights and more willing to demand a better working environment and conditions (International Labour Organization, 2013; 2015). Although life-threatening working conditions are not a major cause of Chinese workers’ collective protests and strikes, those actions do represent workers’ accumulated dissatisfaction and grievances toward the party-state (China Labour Bulletin, 2007; 2009; 2012). The Chinese government’s failure to adequately regulate food and drug safety in recent years further undermines people’s trust in the regime’s capacity to protect their well-being (Manion et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2017; Yan, 2012). Under this circumstance, upsetting news regarding work-related fatalities may raise workers and citizens’ anger to the boiling point, a risk that the party is eager to reduce to the minimum level.

A Puzzling Phenomenon

Well aware of the problem, CCP leaders have made various efforts to reform the work safety regulatory system in the post-Mao era. Major measures included strengthening OSH laws and their enforcement, establishing a responsibility system for local government and production units to handle work-related accidents, increasing investment in safety resources in production units, and strengthening education and publicity on work safety (Bureau of Work Safety of the State Economic and Trade Commission, 2000). During 1980–1999, a work safety management system was established at all levels of the bureaucracy. More than 120 laws and regulations on OSH matters and more than 470 hygiene standards were established and promulgated. Numerous activities related to work safety education, training, publicity, accident investigation, scientific research, and international collaboration were conducted as well (Shan, 2000, p.85).

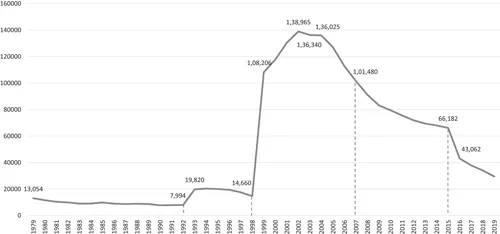

However, despite these efforts, progress in reducing work-related fatalities in this period was not at all encouraging. Figure 1.1 shows the changing trend in the overall fatalities in work-related accidents in China during 1979–2019. It uses the Chinese government’s official statistics on work-related fatalities, but it is important to note that the definition of “work-related fatalities” has been evolving over time. The dotted lines indicate the years when major modifications were made to the statistical methods of defining, calculating, and reporting fatalities in work-related accidents. For example, before 1992, work-related fatalities referred to those that occurred in state-owned enterprises (SOE) and major collective enterprises (MCE) above the county level. In 1993, the scope of work-related fatalities was expanded to include township and village enterprises (TVE), thus resulting in a surge in fatality numbers in that year (from 7,994 in 1992 to 19,820 in 1993). In 1998, the scope of work-related fatalities was further expanded to include fatalities in nine major types of accidents, again resulting in a steep jump in the fatality numbers from 14,660 in 1998 to 108,206 in 1999. Most recently, in 2015, the parameters for work-related accidents were narrowed to exclude those not related to enterprises’ production and operation, resulting in a drop in the fatality number from 66,182 in 2015 to 43,062 in 2016. Therefore, it would be misleading to directly compare the numbers of work-related fatalities without differentiating between periods in which the statistical data were calculated similarly and those in which they were not.

Source: Bureau of Work Safety of the State Economic and Trade Commission, 2000; SAWS, various years from 2002 to 2016. NBS, Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development, 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019.

With that in mind, a key message from Figure 1.1 is that the fatality numbers during 1979–1992 and 1993–1998 were relatively stable, but during 1999–2004 they surged and peaked. Then, a noteworthy turning point came during 2002–2004. For the first time in decades, China’s total number of work-related fatalities, as well as fatalities in various specific types of accidents, dropped. Since then, the numbers have continued to decrease almost year by year. In 2004, work-related accidents caused a total of 136,025 fatalities, a slight decrease over the number in 2003 (136,340). The death toll then dropped all the way down to 66,182 in 2015, a 51.3 percent decrease from the figure in 2003. In other words, work-related fatalities fell by nearly half in the past decade, during which time China also became the world’s second-largest economy. This trend is even more apparent in fatality-to-production ratios. For example, China’s fatality rate per 100 million yuan GDP produced in 2015 was 0.098, a more than tenfold decrease from 2003 (1.170). Likewise, the fatality rate per million tons of coal produced was 0.162 in 2015, a 20-fold decrease over the figure in 2003 (3.724) (Division of Statistics of the State Administration of Work Safety, 2015, p.26). This trend continues to the present day after the revised statistical method was adopted in 2016. It seems that from 2004 onwards, for the first time ever in the history of the PRC, work-related fatalities and accidents have been substantially reduced without jeopardizing the speed of economic growth.

What did the Chinese leaders do in the years of 2002–2004 that transformed work-related fatality reduction—a decades-long pain in the neck—into a mission possible? As with any complicated issue in the field of public policy, the outcome of work safety management cannot be explained by the implementation of any single policy. This study does not discount the important role of various short- and long-term institution-building policies in work safety improvement, such as the upgrading of workplace conditions, the stricter enforcement of work safety laws and regulations, and the enhanced consciousness of work safety in the mindset of local officials, enterprise owners, and workers (Wright, 2012). All those efforts contributed to overall work safety improvement. Nevertheless, this study emphasizes the great importance of the major policy change in China’s work safety management system that occurred around the year of 2004 and its essential role in reversing China’s horrible fatality records. This change, which represents a milestone in the history of work safety regulation in China, is the establishment and implementation of a fatality quota system.

The CCP’s Fatality Quota System

Facing soaring fatalities in work-related accidents and as part of its “people-oriented” policies, the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao administration, which came to office in 2002, prioritized work safety improvement on top of their policy agenda. In 2003, the new administration separated the State Bureau of Work Safety Supervision and Management (guojia anquan shengchan jiandu guanli ju, 国家安全生产监督管理局, SBWSSM) from its previous administrative superior—the State Economic and Trade Commission (guojia jingmaowei, 国家经贸委, SETC), thus making it a more powerful and relatively independent regulator at the national level. The SBWSSM instituted a series of reform efforts to improve work safety. One essential effort was the establishment of a group of fatality quotas, or indicators, that are enforced throughout the bureaucracy. Put simply, these are fatality numbers and ratios that must not be exceeded in various types of work-related accidents. These quotas include both quantity-based standards, which aim to reduce absolute numbers of work-related deaths and accidents, and intensity-based standards, which aim to reduce the rate of death in relation to economic development. Since 2004, the central authorities have prioritized these fatality quotas in the evaluation of local leaders’ annual performance. Quotas are assigned to local governments, professional management departments, and production units. Local leaders and officials in charge of work safety affairs are held strictly accountable for controlling fatalities and accidents within the quotas, and their career will be jeopardized if they exceed the fatality limits.

The fatality quota system was a key pillar of China’s work safety management system during the Hu-Wen administration. In the era of Xi Jinping, China’s work safety regulatory system has undergone significant changes. In 2016, the starting year of China’s 13th five-year plan, the fatality quota system was officially terminated at the national level. Hence, starting that year, the national leaders no longer assigned fatality quotas to provincial-level governments.2 Nonetheless, Xi’s administration still emphasizes the importance of performance management in work safety at the local-government level (State Council, 2016). As the central guidelines were eq...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Note Regarding the Term “Fatality Quotas”

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Blood-Soaked GDP?

- 3 China’s Work Safety Management System

- 4 A Pony Too Small for the Big Cart

- 5 The Fatality Quota System

- 6 Why the Fatality Quotas?

- 7 Has Work Safety Improved?

- 8 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index