![]()

CHAPTER 1

WORKING THE LAND

Let me begin my story by taking you inside one of my earliest childhood memories:

I’m five years old, and I’m sitting on a tractor in one of the tin sheds on my grandpa’s farm in Calhoun County, Texas. As I raise my small hands and grip the wheel, I look out from my perch on the seat of that tractor on this typically hot South Texas morning, imagining the day when I can drive up and down the fields of my grandparents’ farm. Tilling the soil. Pulling the trailer full of hay bales. Feeding the cows. Completing each and every task and chore that needs to be done, as the sun slowly dips in the wide-open blue sky above. Closing my eyes to soak up that image, I feel like I’ve died and gone to heaven. . . .

Farming is very much in my blood, and life on and around the farm provided many of my most important lessons about work and life. Soon after I was born as the oldest of four children and the eldest grandchild, we lived next to my grandparents’ home in a two bedroom house. Inside our large family circle, this little house on the Whatley farm was known as the “Weaning House.” It took its name from its role as the place young couples moved into right after they got married, before they could afford a home of their own. My mom and dad were the first to use it in this capacity.

That Weaning House is gone now, but the home my grandparents lived in for many years still stands, right there on Whatley Road, which was named for my grandparents’ family. That farm had a couple of hundred acres back then, but in the world of farming in Texas, we would be considered one of the little guys.

Farming goes way back in my mother’s family, the Whatleys. My great-grandparents had been farmers in Ireland before they immigrated to the United States in the 1800s to escape the potato famine. After first settling in Alabama, the family eventually moved to Texas. My grandfather was born and raised in Fort Worth, but as a young man he worked at a cotton gin in Austwell, a small community not far from the area where I was raised. He bought his first 160-acre farm close to Austwell in a community called Green Lake soon after the Great Depression of the 1930s, and he just kept going from there.

Having family around was something I always enjoyed. I have very fond memories of visiting my uncle Anthony and aunt Dorothy in Tivoli when I was a boy. A bunch of us kids in the family would take off as soon as we arrived early in the morning, and the grown-ups wouldn’t see us again until dark. We liked to explore the area around “Pee Creek,” so named because the septic system from a few of the surrounding homes ran into it. Surprisingly, the creek didn’t smell all that bad. We knew better than to actually go splashing around in the water, though. We just enjoyed playing on the hillside along the banks of the creek. In the flat lands of Texas, any hill or ditch was always an attraction.

My mom met my dad, Lester Edwin Frazier, in Port Lavaca when they were teenagers. I didn’t hear the story of how they got to know each other until I was much older. My dad was born in Colorado, but his parents divorced when he was ten or eleven, and his father moved to Utah. During my dad’s youth, he lived with his brother for a while. During his stays, he would work in uranium mines nearby driving trucks; but when he was a teenager, he would come down to Port Lavaca in the winter with his mother and his stepfather, Charlie, who sought to escape the cold and snow of Colorado. Since Charlie earned his living as a barber, he was able to find temporary work in Texas.

My father took a risk and bought the local Phillips 66 service station located along Main Street in Port Lavaca, with its population of about 10,000. When Lynda Whatley drove up to that Phillips 66, Lester Frazier apparently took a shine to her.

Well, things have a way of coming full circle in Texas. After my parents moved out of the Weaning House, my father went back to work at that same Phillips 66 station. We lived in Port Lavaca then, and what I remember most about our house was the huge front porch. When I took my kids back to see that house many years later, I discovered that this “huge” porch was no more than twelve feet long and ten feet wide. Strange how we remember things from our childhood as being much bigger than they are.

When they put in the bypass that skirted downtown Port Lavaca, business at the Phillips 66 station dried up. After this, my dad landed a job operating heavy equipment as his primary job for a construction company. Once again, after another transition from that job, we found ourselves back on the farm. This time, instead of working the land on the Whatley farm, we lived and worked on the adjacent Clark farm.

That’s where I really began to learn what it meant to work hard every day. Any time that I was not at school or doing my homework, my dad would send me out into the fields to work with the Hispanic migrant farmhands that he hired. The “Hands” as we called them, lived in houses my family had built for them on the farm and got paid by my father in cash. At one point, long before I was as old as any of those farmhands, my dad even had me directing those guys out there on their tractors working our cotton and other crops. I learned to communicate pretty well in Spanish.

As my mother often said, “When you live on the farm, everybody works.” My younger siblings—my brother Lloyd, my sister Michelle, and my brother Lorne—all played their part as they got older. When I was only nine, my dad taught me to drive the tractor out in the fields. He’d drop me off at first light with my lunch packed, and he’d pick me up at dusk. He even taught me how to drive the farm pickup truck around that time, moving the seat all the way up to the steering wheel just so I could reach the pedal and see out the windshield.

Mom would be right out there in the fields working alongside us, often driving a tractor or grain truck. She likes to tell the story of the night she nearly ran right smack into a black panther. Sometimes Mom would get back to the house late, but she always made time to cook for us. It wasn’t uncommon for us to sit down to a dinner of pancakes.

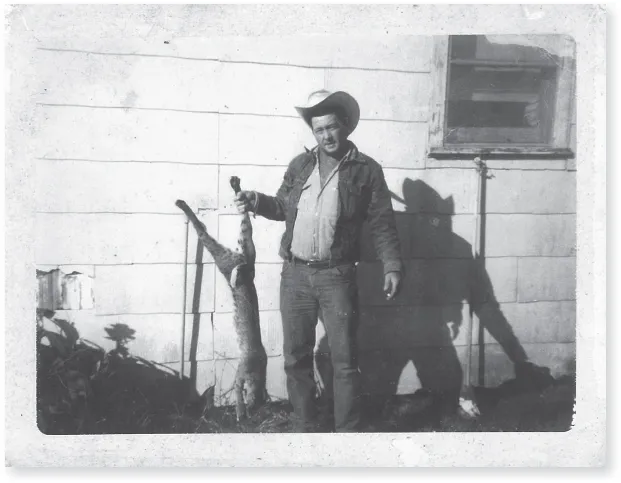

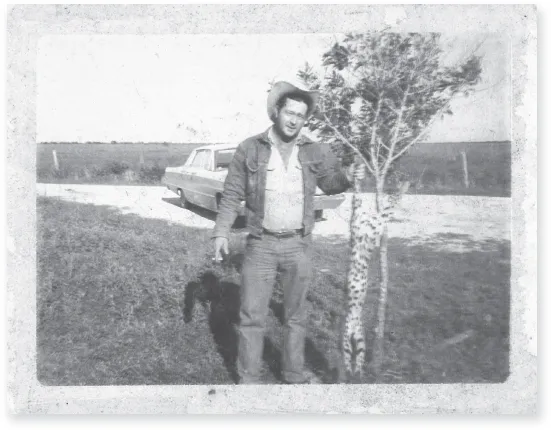

Most of the time, though, we ate very well because Mom was a great cook. Since we had our own chickens, we always had plenty of eggs. We also butchered some of the cattle, sheep, and pigs that we raised, and we hunted deer, wild hogs, quail, and dove. With a winter garden and a summer garden, we had a wide assortment of fresh vegetables and fruit. Our garden would provide us with squash, beets, okra, green beans, cantaloupe, and watermelon; we also enjoyed dewberries, peaches, and oranges from our fruit trees. Some of my favorite meals were fried chicken, venison, and meat loaf.

My dad was very resourceful, always on the lookout for new ways to earn money to feed our family. At one point he raised a couple of thousand rabbits. People would drive south from Houston to purchase these rabbits. Later he would begin to travel to a market twenty-five miles up the road to Victoria, the nearest “big city” from Port Lavaca. I remember toting fifty-pound bags of feed on the feed cart, slowing down at each cage, which had a tray to feed the rabbits.

Much later, after I had gone off to college, my dad began buying and breeding exotic birds. He constructed and organized dozens of bird cages throughout the thick trees behind my parents’ house for all his toucans, macaws, parrots, cockatoos, and yellow-naped amazons, just to name a few. The neighbors would say that they always knew by the screeching when it was feeding time for those birds. When he was just starting out with this venture, my dad ran an ad in the local newspaper inquiring whether anyone was looking for a new home for their pet birds. Believe it or not, some people would just give away their exotic birds, or sell them at a very cheap price. Sometimes my dad might turn around and sell those birds for a nice profit, finding that home they were looking for.

We didn’t continue to work the land on the Clark farm for my entire childhood. At some point we moved into a house that was built in the early 1900s on the Victoria Barge Canal, where my dad plunged into the cattle business as well. We would remain there until I graduated from high school.

That place was near the upper banks on the barge canal with a view of Green Lake, which at two miles wide and thirteen miles in circumference holds the distinction of being the largest natural freshwater lake in the whole state of Texas. The lake got its name from its greenish waters, but make no mistake: This was not some beautiful body of water that people loved to wade and swim in. It was more of a swamp, far more agreeable to the snakes, turtles, and gators that heavily populated it. As my father would say, “You can walk across Green Lake.” The area near our ranch had more than its share of alligators, which we didn’t hunt, although we did hunt the wild hogs.

This was the kind of place that held many mysterious stories about the past. A guy who worked for us would tell of the story of the day the horse he was riding came up lame and stopped to rest on a tree trunk. Upon closer inspection, that tree trunk turned out to be a cannon. As the legend goes, the cannon had been placed there by a pirate who had come up the Guadalupe River with a treasure that he desperately needed to hide. Apparently, that pirate never lived to come back and retrieve his treasure. You can bet that every effort was made by the folks living around there to locate and dig up that treasure. To this day, nobody has found it.

People in South Texas love to tell stories, and they don’t hold back just because you don’t happen to be family or friends. As they would say where I grew up, “People will talk half an hour to a wrong number.”

My dad liked to get out among folks to shoot the breeze when he had the chance. He had a couple of favorite beer joints with pool tables where several of the farmers hung out, and sometimes, when I was a little boy, he had me tag along with him. Now when your dad is drinking his fill at a beer joint, you’ve got to learn to occupy yourself. I would just sit on the floor playing with the pool balls or looking for other things to bide my time. Of course, my dad didn’t let me drink my first beer until I was getting ready to leave for college. That summer he bought me my first beer at the Do Drop Inn beer joint in our hometown of Port Lavaca.

Looking back on my upbringing, I can see how my father’s willingness to change directions and follow new paths to earn a living left a major imprint on me. Many years later, I would come to understand that to fully open the gate to major success, you need to avoid getting stuck trying to follow one straight and narrow path. You’ve got to stay ready to follow all those zigs and zags that will keep showing up along your trail.

My dad’s work ethic also left a big impression on me. From the very beginning, I understood that if you want to fulfill any mission in life, you’ve got to be willing to toil and sweat long hours every day. But if I had to name my dad’s most important influence on me, it would have to be a sense of discipline.

You walked the chalk line with my dad. If you were five minutes late coming home from school, getting back from a date, or showing up in the fields to work the farm, you were grounded. No excuses, no discussion. He used the belt when he believed it was needed to teach you a lesson, and yes, I got the belt my share of times. He would lean me over my bed and deliver my punishment after he caught me picking on my brother Lloyd, who was four years younger than me, or when I didn’t do something I had been told to do.

I loved football and began playing on the seventh-grade team. I remember the day during the following season when my eighth-grade football coach pulled me aside while I was getting dressed for practice. “Lynn,” he said, “what the hell happened to you?” I probably made up some story to cover the truth, but with the bruises and welt lines running from my waist down to the backs of my knees, I wasn’t fooling anybody.

I wouldn’t say that getting the belt made me angry at my dad. Mostly, it just made me afraid. And that fear kept me in line, ensuring that I would do whatever needed to be done each and every time, so as to never get the belt again. No excuses.

...