- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This ninth century history of Alfred the Great's leadership is "a work of extraordinary scholarship that reads with all the narrative style of a novel" (

Midwest Book Review).

In this compelling military and political history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Paul Hill explores England's birth amidst the devastation and fury of the Danish invasions of the ninth century.

Alfred the Great, youngest son of King Æthelwulf, took control of the last surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, bringing Wessex and the "English" parts of Mercia together into a new "Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons." This is a story of betrayal and of vengeance, of turncoat oath-breakers and loyal commanders, of battles fought and won against the odds.

But above all, this is the story of how England came into being.

Warfare in Alfred's England changed from attritional set-piece battles to a grander strategic concern. This is explored, demonstrating how defense-in-depth fortification networks were built across the resurgent kingdom in the wake of Alfred's victory at Edington in 878. The arrival of new Danish armies into England in the 890s would lead to campaigns quite unlike those of the previous generation.

This is a human, as well as a military story: how a king demonstrated the importance of his right to rule. Alfred sought to secure the succession on his son Edward, who led his own forces as a young man in the 890s. But not everybody was happy in Alfred's England. Despite the ever-present threat from the Danes, the greatest challenge facing Alfred arose from his own kin, centered deep in the heart of ancient Wessex. Alfred knew his was not the only branch of the family who claimed a right to rule.

In this compelling military and political history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Paul Hill explores England's birth amidst the devastation and fury of the Danish invasions of the ninth century.

Alfred the Great, youngest son of King Æthelwulf, took control of the last surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, bringing Wessex and the "English" parts of Mercia together into a new "Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons." This is a story of betrayal and of vengeance, of turncoat oath-breakers and loyal commanders, of battles fought and won against the odds.

But above all, this is the story of how England came into being.

Warfare in Alfred's England changed from attritional set-piece battles to a grander strategic concern. This is explored, demonstrating how defense-in-depth fortification networks were built across the resurgent kingdom in the wake of Alfred's victory at Edington in 878. The arrival of new Danish armies into England in the 890s would lead to campaigns quite unlike those of the previous generation.

This is a human, as well as a military story: how a king demonstrated the importance of his right to rule. Alfred sought to secure the succession on his son Edward, who led his own forces as a young man in the 890s. But not everybody was happy in Alfred's England. Despite the ever-present threat from the Danes, the greatest challenge facing Alfred arose from his own kin, centered deep in the heart of ancient Wessex. Alfred knew his was not the only branch of the family who claimed a right to rule.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons by Paul Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE FIRST DANES

When I was with you your loving friendship gave me great joy. Now that I am away your tragic sufferings daily bring me sorrow, since the pagans have desecrated God’s sanctuary, shed the blood of saints around the altar, laid waste the house of our hope and trampled the bodies of the saints like dung in the street. I can only cry from my heart before Christ’s altar: ‘O Lord, spare thy people and do not give the Gentiles thine inheritance, lest the heathen say, “Where is the God of the Christians?”’

Alcuin of York, Letter to Higbald, trans.

by S. Allott, Alcuin of York (York, 1974).

Chapter 1

The Great Suffering

For many hours each day it is not possible to travel on the causeway from the mainland to Lindisfarne. It all depends on the tide: the waters are deceptive and move quickly. Many people still get caught, which is why there is an elevated safety shelter along the way. Once you cross to Lindisfarne though, any feeling of danger dissipates. This beautiful, rugged and windswept place off the coast of Northumbria is one of the key spiritual homes for early Christianity in northern England. The ‘Holy Island’ is still an ideal place for the contemplative life. Close to the rising tide, when you cross from the main island to the small outcrop of rock and grass known as St Cuthbert’s Island, the arms of the sea meet one another behind you and a feeling of isolation takes hold, as the water quickly rises and bubbles around the rocks, sealing you in. Cuthbert himself would have felt it.

Saint Aiden (d. 651) established a community at Lindisfarne, coming in 635 from his base at Iona on the west coast of Scotland at the request of King Oswald of Northumbria (634–42). Later that century St Cuthbert (d. 687), Northumbria’s patron saint, became bishop of Lindisfarne. Both Cuthbert and Oswald would have a part to play in later Anglo-Saxon history long after their deaths. But as Alcuin of York, the expatriate Northumbrian scholar writing from the court of Charlemagne in Francia, so eloquently lamented, the peace here at Lindisfarne was shattered in 793 by pagans. For Northumbria, the sorrowful suffering had begun.

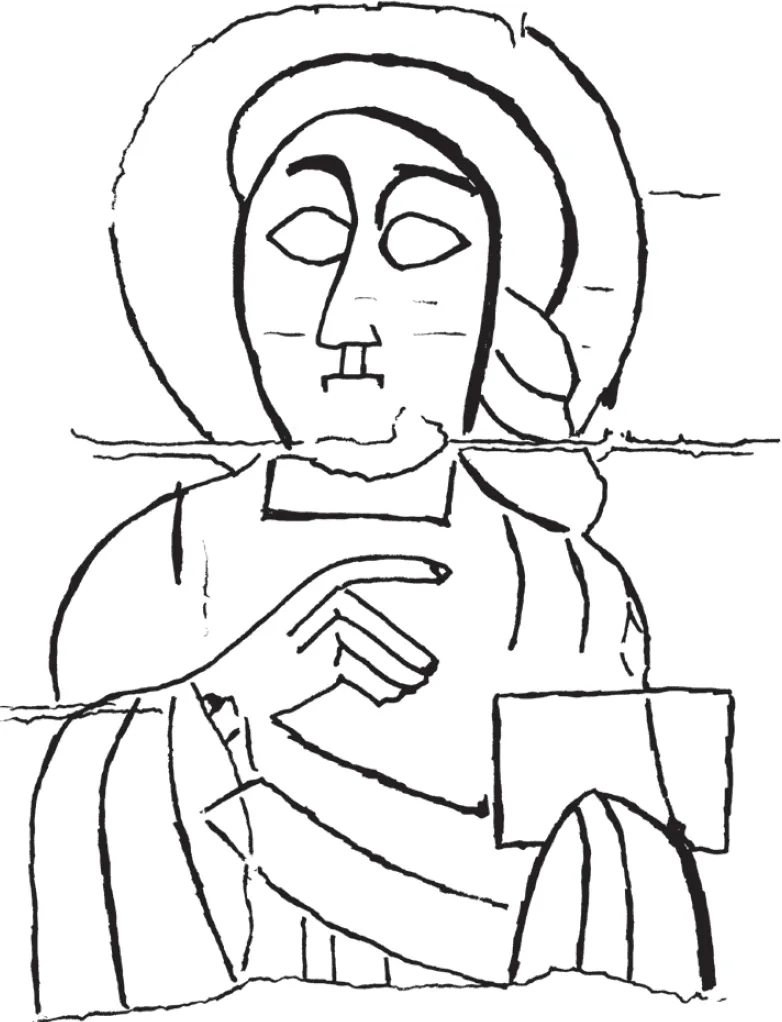

Fig. 1:Carving of an apostle from the coffin of St Cuthbert. (Durham Cathedral)

Since at least the end of the eighth century there had been a seaborne menace emanating from Scandinavia, and the attack on Lindisfarne had not been the only example of Scandinavian violence on English shores. An entry for 789 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells of ‘three shiploads’ of raiders, with some later versions of the chronicle telling of a geographical origin for these ships. They came from Hordaland, a district around Hardanger Fjord in West Norway. This had occurred ‘in his days’ says the chronicler, referring to the reign of King Beorhtric of Wessex (786–802).

Other writers recorded the newcomers as ‘Danes’, just as the earliest version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had done. The Annals of St Neots, which says they were ‘Northmen, that is Danes’, adds that they had landed in the island of Portland, this being the southernmost point of the modern English county of Dorset. Near to here was the West Saxon royal estate at Dorchester. A later tenth-century chronicler Æthelweard, to whom we will return many times, tells us that it was a reeve called Beaduheard who went to the harbour with some of his men having been alerted about the arrivals, believing them to be merchants. Usually, such visitors might be Frankish, Frisian or other traders, familiar with the protocols to be observed at their port of landing and with their requirement for accountability. But there was nothing ‘usual’ about this little flotilla. Their ships were fitted out with gaudily-striped sails and their prows were fashioned like dragons’ heads. Beaduheard was keen to have the intruders brought to King Beorhtric’s town of Dorchester, or more probably, to the nearby ‘Kingston’, a royal settlement where the king could deal with them. Unsure of who they were, he knew at least that ‘merchants’ from afar often brought news of the world they travelled in. The king would surely be keen to hear of it. Also, the reeve would need to be sure that he took a head count of the ‘merchants’ so that he and his king knew how many men had come to do business in the kingdom. Beaduheard gave orders for the men to be seized and brought to the king. Anyone looking down from the highpoint of the promontory overlooking Portland will have seen the three ships drawn up on the shore and the men and horses of the king’s reeve as they approached the occupants. The drama which then unfolded will have shocked any observer. Beaduheard, we are told by Æthelweard, spoke to these new arrivals ‘haughtily’. In cold blood, they slaughtered the reeve and his companions on the spot.

1. Holy Island (Lindisfarne) causeway safety shelter at low tide.

Marchlanders

The original Mercian heartlands lay north and south of the Upper Trent. However, the early history of this mainly Anglian kingdom is one of expansion, particularly to the south and west. The northern boundary of Mercia in the west eventually followed the line of the Mersey (the name mæres ea means ‘boundary river’, just as the related Mierce indicated ‘the march dwellers’ or ‘Mercians’). Other earlier Mercian boundaries may well have been in the central Midlands adjacent to Celtic groups. To the north of the Mercians were the Northumbrians.

The dates for the early rulers of Mercia are unclear, with the genealogies only giving more reliable names and dates after the time of Penda (whose reign began in 626/32). A king called Creoda held power, probably around 585. His son was Pybba (c. 593–c. 606/16) who was followed by Cearl (fl. c. 610–c. 625, about whom little is known), who was then followed by Pybba’s famous pagan son Penda (who reigned to 655). According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Penda’s lineage went back five generations to the semi-legendary Icel of the sixth century, who as ruler of Angeln led his people into Britain over the North Sea. According to legend, Icel was descended from the god Woden and he gave rise to the line of the Iclingas, who continued in Mercia up to the reign of Ceolwulf I (d. 823).

Penda’s reign was long and eventful. In 628 a campaign against the West Saxons at Cirencester resulted in his enemy ceding the territory of the ancient kingdom of the Hwicce to Mercia. In 633 he participated in campaigns leading to the downfall of Edwin of Northumbria. It was Penda’s forces who killed the pious Oswald of Northumbria in c. 642 whose cult grew in importance during the tenth century. It was also Penda who drove out the West Saxons again in 645 and it was probably Penda who killed Anna of the East Angles in 654. Penda himself would be the last pagan king of Mercia.

The Tribal Hidage

The Tribal Hidage lists thirty-five Anglo-Saxon tribes in central and southern England and reads to some like a Mercian tribute list (though to others, like a Northumbrian invention re-defining Mercian groups). It rated each group in terms of ‘hides’, that is, the notional unit of land needed to sustain one family. One grouping is described as ‘the first land of the Mercians’ and is assessed at 30,000 hides. It is thought to comprise Staffordshire, parts of Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. Other groups include the Wrocensæte of Shropshire, the Pecsæte of the Peak District and the Arosæte who lived along the River Arrow north of the Hwiccian territory. The Magonsæte, who were based just north-west of Hereford, are not listed but it is known that an early king was Merewalh, a possible son of Penda.

The peoples of Middle Anglia were brought under Mercia’s sway by Penda who made his son Peada king over them in 653, but who died within a few years. Penda also subjected the kingdom of East Anglia to Mercia. But Penda was killed by Oswiu of the Northumbrians at the Battle of Winwæd in 655. Peada, Penda’s son and successor (who died in 656 at the hands of his Northumbria wife) ruled only over southern Mercia with Northumbria taking the northern part, its dividing line being the Trent.

Whatever the West Saxon king Beorhtric thought of the carnage on his coastline can only be guessed. It was hardly Beaduheard’s fault that he enquired of the newcomers their intention. Nor was it particularly common for a reeve on the king’s business to approach such matters as a shrinking violet. His ‘haughtiness’ was merely part of the job. After all, Beaduheard’s chief concern was what these men could provide for his king either by income, information, or if a threat was posed, by elimination. But on this day, he rolled poor dice. Three shiploads of warriors simply overwhelmed him and his men.

Beaduheard’s king, Beorhtric, ruled over the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex. However, the main power in England at the time of these first Scandinavian incursions lay with a Mercian king, Offa (757–96). This remarkable king, later described by Alfred’s biographer Asser as a ‘tyrant’, was long remembered in central England, and to some extent still is. He had expanded Mercian control beyond its traditional borders by taking control of Kent in the 760s and Sussex in 771. London had already come under his sway and from here he issued a new coinage. Moreover, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of East Anglia and Essex also felt the reach of Offa’s power at its height.

Offa’s achievements in Mercia were profound. For example, he is traditionally credited with the introduction into Mercia (and by association, England) of the silver penny, although there is a debate as to whether he may have copied some Kentish types. Also, both the Frankish ruler Charlemagne (d. 814) and Pope Hadrian I (772–95) were involved in securing the rare visit to England in 786 of papal legates. Pope Hadrian was also involved in another matter, the short-lived creation of the archbishopric of Lichfield, a development probably linked to Canterbury’s refusal to back Offa’s bid to secure the royal succession for his son Ecgfrith. Offa also traditionally founded St Albans Abbey, which became a great seat of learning to rival any south of the River Thames or north of the River Humber. Offa’s influence and power were well noted: he was called ‘an extraordinary man’ by the chronicler Æthelweard, writing some two centuries later. There were doubtless many contemporaries as fearful as they were impressed. The Welsh kings could scarcely ignore Offa’s Dyke, the gigantic monument to the Mercian kingdom’s organizational capabilities which stretched for some 64 miles along their eastern borders.

Beorhtric married the daughter of King Offa. This woman’s name was Eadburh. The evidence would suggest that she was a fascinating, influential and dangerous character. We will encounter her entertaining, though rather sorrowful, contribution to English history in due course. Suffice it to say, that Beorhtric had apparently assisted his father-in-law by driving out of England his main rival for the throne of Wessex, one Ecgberht. This West Saxon exile, Alfred’s grandfather, spent several years in Francia patiently waiting to return whilst no doubt learning much from his Carolingian hosts. The length of time for the exile is generally thought to have been three years but could well have been thirteen instead, as it is argued an ‘x’ may be missing from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s record of the years. In a twist not mentioned elsewhere, however, William of Malmesbury, writing in the twelfth century, says that Ecgberht spent some time at King Offa’s court because he had found out that Beorhtric was plotting to kill him. It was the result of Beorhtric’s pressure on Offa, says William, which led to Ecgberht’s Frankish exile.

2. Offa’s Dyke. Traditionally associated with King Offa (757–96), it may be the cumulative product of numerous Mercian rulers over time. Parts still stand today as testimony to the organizational capabilities of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The Mercian Ascendancy

By 665 Peada’s brother Wulfhere (658–74) had restored some independence to Mercia after the disastrous defeat at Winwæd ten years earlier, where Penda was killed by the forces of Oswiu. During his time Christianity continued to flourish and a Bernician monk named Chad came from the north and was appointed bishop of Mercia in 669. He moved his seat from Repton to Lichfield.

Wulfhere, although more of a diplomat than an expansionist warrior, was not averse to campaigning. He raided as far south as the Isle of Wight in 661 and handed it to the king of the South Saxons. He drove the West Saxons, the Gewisse, out of their homelands in the Upper Thames Valley. He also extended Mercian control over the Hwicce, but he was defeated in 674 by the Northumbrians. His brother Æthelred married a Northumbrian princess and succeeded Wulfhere in Mercia in 675. Æthelred raided into Kent and won a victory over the Northumbrians at the Battle of the Trent in 679. Importantly, this returned the kingdom of Lindsey (roughly the area of modern-day Lincolnshire) to Mercian control. But by 704 Æthelred decided to abdicate. His Northumbrian wife Osthryth (who was strongly associated with the cult of St Oswald) had been murdered in 697 and this seems to have turned the king’s world upside down. He became a monk at Bardney, a monastery they had founded together, and was buried there.

Coenred (704–09), son of Wulfhere, was also a pious man, and he also abdicated. He fled to Rome on pilgrimage. Coelred succeeded him. In 715 or 716 he fought against the West Saxon king Ine but little is known of the campaign. Then Æthelbald (716–57), a great-nephew of Penda, was next on the throne. In 733 he captured Somerton in Somerset from Wessex. In 740, after a long period of peace with Northumbria, he raided across its border. In the same year there were campaigns against Wessex. However, Æthelbald also received help from Wessex against the Welsh, although there were more campaigns against Wessex in 752. Then, in 757 Æthelbald was dramatically killed by his bodyguards at Seckington, not far from Tamworth. He was interred at Repton. His successor Beornred, whose ancestry is not known, did not survive on the throne long. He was ousted by Offa (757–96) and with this new and powerful king, the period of Mercian supremacy over the other kingdoms of the old Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy continued.

By the early ninth century, however, Mercian dynasties began to compete for the throne against a backdrop of the rising power of their West Saxon neighbours. These families are sometimes referred to as the ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘W’ dynasties due to the alliteration in their names. Their support for Mercian kings, including elevating candidates of their own, was a dominant feature of the early ninth century.

Domestic dynastic politics seems not to have been greatly affected by the early Scandinavian attacks. However, as we have seen, one incident in particular at Lindisfarne had sent shock waves around all of Western Christendom. Alcuin’s eloquent words were not the only ones to be written about it. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also dramatically records the raid. The heathens, it says, ‘miserably devastated God’s church on Lindisfarne Island by looting and slaughter’. The report is presaged by ‘terrible portents which overcame Northumbria’. Flashes of lightning and fiery dragons were seen in the sky, says the chronicler, and then a famine immediately followed. By presenting it like this, not for the first or last time, the chronicler added gravitas to his account and gave it an overwhelming sense of foreboding.

The language is no less dramatic elsewhere. In material drawn from a set of early Northumbrian annals amongst a compilation usually attributed to Symeon of Durham (Historia Regum LVI), though probably originating much earlier at Ramsay, the ransacking of Lindisfarne is given a very human consequence: ‘they killed some of the brothers, took some away with them in fetters, many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults, some they drowned in the sea’. Altars, it was said, were dug out, silver and relics were stolen and monks sold into slavery. This latter category of prize, the slave, must have lived a mournful existence. Across Europe, and in the eastern world of Byzantium and the Islamic Caliphate, there was clearly a huge market for slaves, each with a personal story to tell. Usually, the raiders who stormed the monasteries chose the young ones, if Alcuin’s letters are anything to go by. Alcuin hinted that because he had the ear of Charlemagne, he might just be able...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Photograph Credits

- List of Maps and Plans

- A Note on the Charters

- Introduction

- PART ONE: THE FIRST DANES

- PART TWO: THE KINGDOMS COLLAPSE

- PART THREE: THE REBUILDING

- PART FOUR: A DIFFERENT KIND OF WAR

- Bibliography

- Plate section