eBook - ePub

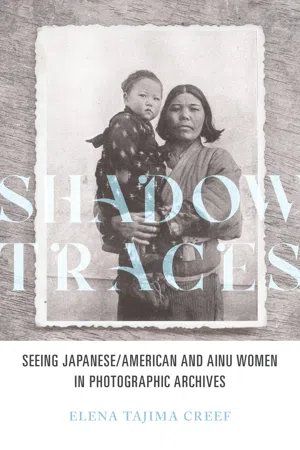

Shadow Traces

Seeing Japanese/American and Ainu Women in Photographic Archives

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Images of Japanese and Japanese American women can teach us what it meant to be visible at specific moments in history. Elena Tajima Creef employs an Asian American feminist vantage point to examine ways of looking at indigenous Japanese Ainu women taking part in the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition; Japanese immigrant picture brides of the early twentieth century; interned Nisei women in World War II camps; and Japanese war brides who immigrated to the United States in the 1950s. Creef illustrates how an against-the-grain viewing of these images and other archival materials offers textual traces that invite us to reconsider the visual history of these women and other distinct historical groups. As she shows, using an archival collection's range as a lens and frame helps us discover new intersections between race, class, gender, history, and photography.

Innovative and engaging, Shadow Traces illuminates how photographs shape the history of marginalized people and outlines a method for using such materials in interdisciplinary research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shadow Traces by Elena Tajima Creef in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Frauen in der Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Those “Mysterious Little Japanese Primitives”

“Here is the Most Interesting Pair in the World’s Fair Anthropological Exhibit: Shutratek, the Ainu Mother, and Kiku, the Baby Daughter, are a Center of Attraction—Kiku is Very Like a Japanese Doll.”—St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1904

The Ainu at the Fair: The “Aborigines of the Japanese Empire”

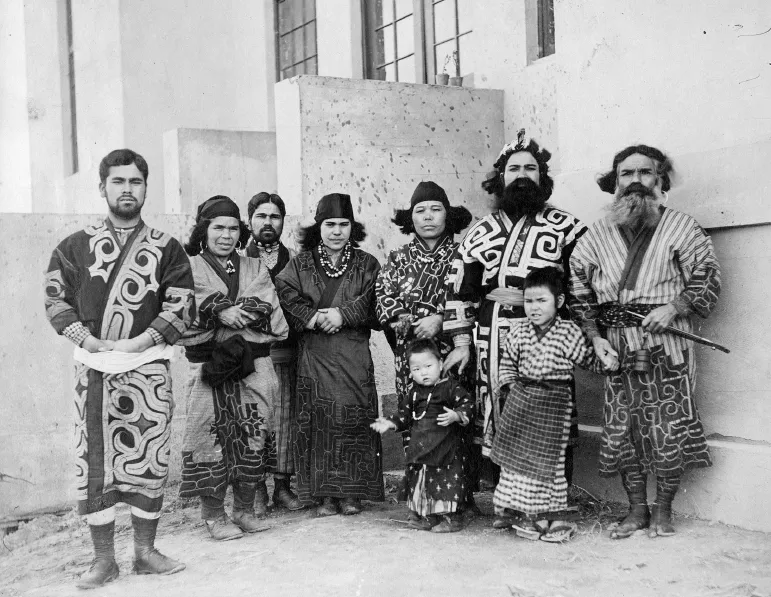

The 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair was an event designed to showcase the grandeur of empire, the supremacy of western technology, industry, and culture while commemorating the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase—an event that many scholars have argued consolidated the American nation and empire. As Martha Clevenger notes, the 1904 fair occupies a unique place in US history and was sandwiched between the Gilded Age and World War I.1 In the seven months the fair was open, over twelve million paying visitors attended the fair, which officially opened its doors on April 30 (closing December 1) and featured exhibitions from fifty foreign nations, and from forty-three of the forty-five US states. One of the most popular cultural attractions at the fair included a group of nine indigenous Japanese Ainu who were part of an ambitious anthropological exhibition of “living groups” under the direction of W. J. McGee, chief of the Anthropology Department at the exposition.2 They included two families, Sangyea, Santukno, Kin Hiramura and Kutoroge, Shutratek, and Kiku Hiramura; one couple, Yazo and Shirake Osawa; and a bachelor, Goro Bete.

According to anthropologist James W. Vanstone, McGee had envisioned “extensive ethnographic exhibits located on an extensive ‘anthropological reservation’ where ‘representatives of upwards of thirty living groups were to be seen in native dress, living in houses of their own construction, cooking and eating the food to which they are accustomed at home, and practicing those simple arts and industries, which they have themselves developed.”3

In March of that year, the American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal reported on the fair’s progress:

Plans have been completed for assembling, either in the Department of Anthropology or elsewhere, representatives of all the world’s races, ranging from the smallest pygmies to the most gigantic peoples, from the darkest blacks to the dominant whites, and from the lowest known culture (the dawn of the Stone Age) to its highest culmination in that Age of Metal, which, as the Exposition shows, is now maturing in the Age of Power.Arrangements are well advanced for placing family groups representing various other primitive peoples on the grounds of the department. Among these are the Ainu tribe of the Island of Hokkaido (Northern Japan), representing the aborigines of the Japanese Empire, and illustrating in their occupations and handiwork some of the most significant stages in industrial development known to students—germs of some of those material arts which in their perfection have raised Japan to leading rank among the world’s nation.4

The Ainu group was procured by University of Chicago anthropologist Frederick Starr, who McGee commissioned to travel to northern Japan in search of at least “eight good specimens” to bring back to St. Louis.5 Much of our information about the Ainu who traveled to St. Louis comes from Starr’s 1904 book chronicling this expedition, The Ainu Group at the Saint Louis Exposition—with images by Starr’s longtime personal photographer, Manuel Gonzales.6 In 1904, anthropologists considered the Ainu to occupy an ambiguous racial position; Starr himself infamously asked, “Who are the Ainu? Where did they come from? What is their past? They are surely a white people, not a yellow…. We take it for granted that all white men are better than any red ones, or black ones, or yellow ones. Yet here we find a white race that has struggled and lost!”7

To launch this book’s examination of photographic representations of Japanese/American women, the visual archive surrounding the Ainu group at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition provides both a rich and unusual place to begin. As a rule, indigeneity usually falls outside the purview of Asian/American histories of representation. As the indigenous people of Japan, the Ainu rightfully occupy a place outside the binary designation “Japanese/American”; yet, as “indigenous Japanese,” I include them in this book because of the prominent archival record that surrounds their brief time in America. Furthermore, the Ainu at St. Louis have received scant critical attention from US scholars over the past one hundred years.8 What remains particularly striking about their story is the fact that out of the nine individuals who were recruited from northern Japan to participate in St. Louis, the majority were female: three wives and two little girls.9 Yet, to date, virtually no one has considered how “gender” has not only shaped, but in many ways dominates, this visual archive. The five females of the Ainu group have indelibly—and dramatically—left their mark across the visual and anthropological archives of the Frederick Starr Papers, the local and national newspaper coverage of the fair, and the striking work of fair photographers like Jessie Tarbox Beals.10 This chapter explores how a critical feminist revisiting of these American archival collections pedagogically invites us to read against the representational grain, as it were, for a closer critical examination. While Japanese Ainu do not traditionally fit into the larger history of “Asians” in America, as unique turn-of-the-century travelers caught by the camera at one of the key historical and cultural events in turn-of-the-century America, they deserve to be included in a reframing of early Japanese/American visual history courtesy of the kind of critical inquiry afforded by a women’s and gender studies lens.

In her superb study of early women photographers, Laura Wexler cites James Scott’s notion of “hidden transcripts” that haunt historical photographic records and prompt us to look more deeply if we wish to learn how to decode “encrypted resistance” in “official records of compliance.”11 With Scott’s notion of the “hidden transcript” in mind, what might we uncover by looking more closely at the 1904 Ainu group that others have missed? What kinds of counter memories or readings might we retrieve or reconstruct based on incomplete or partial records that chronicle the haunting presence of the Ainu women and young girls at the fair? How might we scrutinize their photographic traces? What might we find in the anthropologist’s handwritten field notebooks or even personal scrapbooks that others have overlooked?

The Ainu Group and the Performance of Racial and Gendered Spectacle

While the Ainu were part of the larger living anthropological exhibit at the fair, and were in fact recruited to perform their indigeneity as a form of entertainment for a curious American public, one could say that their performance began as soon as they left Japan. According to Starr’s travel narrative, the Ainu were framed as “spectacle” as soon as they left Yokohama on March 18 onboard the SS Empress of Japan. An outraged Starr recalls how the Ainu were invited to contribute to the ship’s entertainment program under an insulting and dehumanizing misnomer:

We were invited to contribute … to the program by bringing in the Ainu and making an address about them. The address was well received but gave occasion to a little sparring. We did not see the program until it was printed and then found that we were announced to present a “short description of the Aino, followed by an Aino bear-dance by three of the tribe on board.” Our people were in ceremonial dress and made a fine appearance….Had we seen the program, we should not have permitted the word Aino to appear upon it; nor should we have allowed announcement of a “bear-dance” of which we never heard…. As to the name of our people it is not Aino, but Ainu, which is a word in their own language meaning man…. The word Aino is neither an Ainu nor a Japanese word; it approaches the Japanese word ino, “dog,” and there is no doubt that this similarity shades the word when used by the Japanese, to whom the Ainu often are as “dogs” and who have a legend that the Ainu are really the offspring of a woman and a dog.12

The anthropological lectures that Starr would deliver onboard the Empress of Japan on Ainu life and customs—with members of his Ainu delegation giving live demonstrations—would be reprised along their journey once they arrived in Vancouver, Canada, and then traveled by train from Seattle, Washington, through Sheridan, Wyoming, to their final destination in St. Louis, Missouri.13 Starr notes that the Ainu were objects of visual fascination for all those who beheld them: “at almost every station passed during the daytime, people crowded to see the Ainu and asked their questions and made their comments but all good-naturedly. Several adventures with drunken men upon the car took place, but these poor fellows were usually bubbling over with goodwill and were only troublesome in their well-meant advances of kindness.” Starr also records two occasions during their journey where the Ainu encountered Native Americans and African Americans with whom they exchanged what he calls “mutual inspection”: “At Fort Sheridan, Wyoming, negro soldiers were at the station. Kutoroge was greatly excited and examined them closely. He finally asked us whether the color was temporary or permanent, and then wanted to know whether it was generally distributed over the body or confined to the face and hands.”14 Starr’s inclusion of these brief cross-racial encounters reminds us that the Ainu group were not merely passive objects who were scrutinized by others, but that they themselves held their own counter-gaze with full curiosity and engagement.

According to Starr, the public performance of indigeneity en route to St. Louis was also not just limited to the Ainu adults. In Vancouver, as guests of the local Japanese mission, the entourage appeared in a lecture room where the two little girls, Kin and Kiku, were also put on display, becoming instant crowd favorites. Starr describes how in exchange for toys and bonbons the little girls were coaxed into giving a show of “salutation, thanks, and petition” for the amusement and delight of those watching the Ainu show:

This trick of Kin and Kiku is one which Manuel [Gonzales] discovered and has a bit developed. On shipboard, when we carried lumps of sugar or fruits or cakes down to the children, as we did every afternoon, we insisted on their standing to receive them. On seeing the gift, the little hand was raised and the finger drawn across the upper lip, then the two hands were crossed one on the other, palms up, just in front of the body, when the gift was laid upon them. It was very pretty, particularly when done by little Kiku. Rarely have we seen such general interest and close attention as this crowd of young Japanese gave throughout our little entertainment. At its close they showered gifts upon the Ainu. The men each received a dollar; each woman received cloth for a dress; the children were given toys and bonbons.15

One of the rare published photographs depicting Starr’s accompanying photographer, Manuel Gonzales, appears in the anthropologist’s 1904 book, The Ainu Group at the Saint Louis Exposition. In one particularly moving image, the smiling Gonzales squats at eye level next to “little Kiku.” The camera captures Gonzales’s obvious pleasure in interacting with the child, who is shown performing the very same salutation of thanks described above. While the appearance and performance of the little girls Kin and Kiku were deemed not only charming but even a “very pretty” spectacle, the US press coverage of the traveling Ainu group repeatedly reveals an ambivalent cultural fascination mixing admiration together with repulsion aimed at the three indigenous women. It is worth looking more closely at some of the newspaper representations of the Ainu group that vividly documented their journey to St. Louis.

The coverage began immediately upon their arrival in North America. Across the country, the Washington Post noted that “The Canadian Pacific steamer Empress of Japan arrived [in Vancouver] from Yokohama today. Among her passengers were a party of Hairy Ainus from the island of Hokkaido, in charge of Professor Fred Starr, lecturer in the department of anthropology at the University of Chicago…. The men are small, but well proportioned, and have long beards and intelligent faces. The women are handsome and dress in gaudy costumes.”16 In turn-of-the-century popular and anthropological literature, the Japanese Ainu are deemed the “Hairy Ainu” based on the observation that the men were able to grow full beards and po...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Those “Mysterious Little Japanese Primitives”

- 2 Looking at Japanese Picture Brides

- 3 Beauty behind Barbed Wire

- 4 Filling in the Blank Spot in an Incomplete War Bride Archive

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index