eBook - ePub

Climate Change and Infrastructure, Urban Systems, and Vulnerabilities

Technical Report for the U.S. Department of Energy in Support of the National Climate Assessment

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Climate Change and Infrastructure, Urban Systems, and Vulnerabilities

Technical Report for the U.S. Department of Energy in Support of the National Climate Assessment

About this book

Hurricane Irene ruptured a Baltimore sewer main, resulting in 100 million gallons of raw sewage flooding the local watershed. Levee failures during Hurricane Katrina resulted in massive flooding which did not recede for months. With temperatures becoming more extreme, and storms increasing in magnitude, American infrastructure and risk-management policies require close examination in order to decrease the damage wrought by natural disasters. Climate Change and Infrastructure, Urban Systems, and Vulnerabilities addresses these needs by examining how climate change affects urban buildings and communities, and determining which regions are the most vulnerable to environmental disaster. It looks at key elements of urban systems, including transportation, communication, drainage, and energy, in order to better understand the damages caused by climate change and extreme weather. How can urban systems become more resilient? How can citizens protect their cities from damage, and more easily rebound from destructive storms? This report not only breaks new ground as a component of climate change vulnerability and impact assessments but also highlights critical research gaps in the material. Implications of climate change are examined by assessing historical experience as well as simulating future conditions.

Developed to inform the 3rd National Climate Assessment, and a landmark study in terms of its breadth and depth of coverage and conducted under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy, Climate Change and Infrastructure, Urban Systems, and Vulnerabilities examines the known effects and relationships of climate change variables on American infrastructure and risk-management policies. Its rich science and case studies will enable policymakers, urban planners, and stakeholders to develop a long-term, self-sustained assessment capacity and more effective risk-management strategies.

Developed to inform the 3rd National Climate Assessment, and a landmark study in terms of its breadth and depth of coverage and conducted under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy, Climate Change and Infrastructure, Urban Systems, and Vulnerabilities examines the known effects and relationships of climate change variables on American infrastructure and risk-management policies. Its rich science and case studies will enable policymakers, urban planners, and stakeholders to develop a long-term, self-sustained assessment capacity and more effective risk-management strategies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Climate Change and Infrastructure, Urban Systems, and Vulnerabilities by Thomas J. Wilbanks,Steven Fernandez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The third U.S. national assessment of climate change impacts and responses, the National Climate Assessment (NCA), includes a number of chapters summarizing impacts on sectors, sectoral cross-cuts, and regions. One of the sectoral cross-cutting chapters is on the topic of urban/infrastructure/vulnerability implications of climate change in the U.S.

As a part of the NCA effort, a number of member agencies of the U.S. Global Change Research Program provided technical input regarding the topics of the NCA chapters. For the urban/infrastructure/vulnerability topic, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is one of the responsible agencies; and this report was prepared for DOE by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in support of the NCA. DOE’s interest grows out of a longstanding research focus on energy infrastructures and their relationships with other infrastructures and systems, such as water and land, led by the Climate and Environmental Systems Division of the Office of Science.

Unlike many of the other chapters, which have equivalents in previous national assessments, this particular topic is appearing in NCA for the first time. In past assessments, cross-sectoral issues related to infrastructures and urban systems have not received a great deal of attention; and, in fact, in some cases the existing knowledge base on cross-sectoral interactions and interdependencies, at least as represented in published research literatures, appears to be quite limited. Studies dating back as far as 1982 (Lovins and Lovins, Brittle Power) have, however, pointed to the vulnerability of large, complex infrastructures to large-scale failures, and this underlying concern has grown in recent years (e.g., Villasenor, Brookings, “Securing an Infrastructure Too Complex to Understand,” September 2011).

As a result, this technical report breaks new ground as a component of climate change vulnerability and impact assessments in the U.S., which means that some of its assessment findings are rather speculative, more in the nature of propositions for further study than specific conclusions offered with a high level of confidence. But it is a welcome start in addressing questions that are of interest to many policymakers and stakeholders.

For broader issues related to social as well as infrastructural aspects of climate change vulnerabilities and risk management strategies in urban areas, this technical report should be read in conjunction with a second technical report on U.S. Cities and Climate Change: Urbanization, Infrastructure, and Vulnerabilities, supported by NASA. For more attention to energy/water/land use interactions, see an additional technical report on that topic, also supported by DOE.

All of the technical reports to the NCA were prepared on a highly accelerated schedule. As an early step in organizing the NCA, a workshop was held in November 2010 to discuss sectoral and regional assessment activities. Out of that workshop came a number of further topical workshops and a working outline of the NCA 2012 report, including sectoral, regional, and cross-cutting chapters. In the summer of 2011, a number of USGCRP agencies stepped forward to commission technical input reports – each with at least one expert workshop and with a submission deadline of March 1, 2012, condensed into a period of eight months or less. Meanwhile, the advisory committee for the NCA (NCADAC) has appointed author groups for the report chapters, who incorporated the technical input in a draft NCA report to be submitted to the U.S. Congress by early 2014 (see www.globalchange.gov).

This report benefited from a scoping workshop on July 20, 2011, and an expert workshop November 9-10, both in Washington, DC. A final draft of the full report was sent to eleven distinguished external reviewers, eight of whom provided extensive comments and suggestions that were incorporated in this document.

The report includes substantial sections on “framing climate change implications for infrastructures and urban systems to climate change,” considering both sensitivities to climate change and linkages among infrastructures, and on “urban systems as place-based foci for infrastructure interactions.” These sections are followed by sections on implications for risk management strategies, research gaps, and developing a self-sustained assessment capacity for the longer term.

Chapter 2

Background

A. The Development Of The Report

1) OVERVIEW

This report is a summary of the currently existing knowledge base on its topic, nested within a broader framing of the issues and questions that need further attention in the longer run. The main constraint at this time is the limited amount of research that has been conducted and reported in the open literature on interactions between different categories of infrastructure under conditions of stress and/or threat. Given this rather severe constraint, findings in this report about climate change implications for infrastructures and urban systems are necessarily weighted somewhat toward research gaps and needs as contrasted with specific vulnerabilities; but a number of general assessment findings, reflecting a high level of consensus, add richness to NCA’s understanding of cross-sectoral impacts and risks.

2) APPROACH

This report was developed by an author team led by ORNL under the oversight of DOE, with significant input from a range of expert communities at the two workshops in Washington, DC. Data, methods, and tools depended on available source materials and varied according to the topic and the resources that have been invested in each particular topic, except for one case study of climate change implications for urban infrastructures in Miami that was carried out by LANL and ORNL using critical infrastructure simulation and analysis tools developed initially for use by DHS. Judgments about report content, assessment findings, and levels of confidence reflect group consensus among the report authors, considering comments from selected external reviewers.

3) NCA GUIDANCE

The NCA adopted a range of types of guidance for the technical reports covering eight topics that are priorities for the 2014 report: risk-based framing; confidence characterization and communication; documentation, information quality, and traceability; engagement, communications and evaluation; adaptation and mitigation; international context; scenarios; and sustained assessment (www.globalchange.gov/what-we-do/assessment/nca-activities/guidance). The ability to respond to this guidance was limited by several factors. First, the content of the report is based as much as possible on available sources of technical literature, which varied considerably in their treatment of such issues as scenarios and confidence characterization. In most cases, in fact, the sources do not refer to climate change scenarios at all. Second, the nature of much of the source material, often qualitative and issue-oriented, severely limited any attempt to estimate quantitative bounds on probabilities. And third, the highly compressed time schedule for the technical report preparation process limited potentials for engagement and communication and made it difficult to impose top-down strictures on report authors.

Given a body of source material that is a highly imperfect fit with the NCA guidance, the report has made an effort to frame its assessment findings in broad contexts of risk-based framing, scenarios, and confidence characterization. Assessment findings are associated with evaluations of the degree of scientific consensus and the strength of the available evidence. Where appropriate, findings are also associated with two general scenario-related framings of possible future climate changes: (1) “substantial”, which is approximated by IPCC Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES) emission scenario A2, and (2) “moderate”, which is approximated by scenario B1.

4) ASSESSMENT FINDINGS

Assessment findings are provided at the end of each major section of the report, including sections on risk management strategies; knowledge, uncertainties, and research gaps; and developing a sustained capacity for continuing assessments. The complete list of twenty assessment findings is included in the report’s Executive Summary.

B. The Scope Of The Report

1) HOW “INFRASTRUCTURES” ARE DEFINED

For this study, the emphasis is on built infrastructures (as contrasted, for instance, with social infrastructures). Such infrastructures include urban buildings and spaces, energy systems, transportation systems, water systems, wastewater and drainage systems, communication systems, health-care systems, industrial structures, and other products of human design and construction that are intended to deliver services in support of human quality of life.

Experience over the past decade has shown vividly how vulnerable such infrastructures can be to the types of extreme weather events that are projected to be more intense and/or more frequent with future climate change. For instance, the Gulf Coast continues to be highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change despite rebuilding and new design features for infrastructure. While additional protection has been provided in the form of new levees and other structures; higher, stronger and better engineered roads and bridges; and more complete monitoring and communications equipment; the magnitude of the potential impacts of sea-level rise, storm effects and heat -- in conjunction with ongoing changes in the natural environment -- will continue to require attention and investment for a considerable time to come.

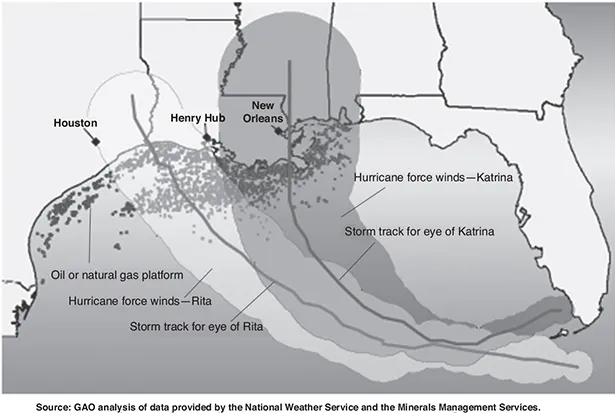

In 2008, the U.S. Global Change Research Program issued a “Gulf Coast Study” (SAP 4.7, 2008) that detailed the impacts of climate change on the central Gulf Coast from Houston to Mobile, AL. The study concluded that two- to four-feet of relative sea level rise were likely to occur in the region by 2050, including the continuing subsidence of the land mass (unrelated to climate change) (Figure 1). More recent estimates indicate that sea-level rise by 2100 may be twice as great as this study assumed, based at that time on lower projections by the IPCC in its Fourth Assessment Report in 2007.

Figure 1 Path of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita relative to oil and natural gas production platforms

Our expanding understanding of climate stressors is complemented by an enhanced understanding of how infrastructure and the services they provide are at risk. The Gulf Coast Study found that approximately 2,400 miles of major roads, 246 miles of railways, 3 airports and three-quarters of the freight facilities would be inundated by a four-foot rise in sea level. It further found that more than half of the major roads and all of the ports were susceptible to flooding from a storm surge of just 18 feet. By comparison, Katrina’s surge was estimated at 28 feet at landfall. As stark as these direct impacts are, the ripple effects of damaged infrastructure on other essential services poses an even more complex set of challenges. In the ensuing analysis of impacts of Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Ike, lessons were learned about the interdependence of various types of infrastructure and how interdependencies exacerbate the vulnerabilities of critical services. In this region, fuel supply, shipping and communications were all disrupted as a result of interruptions in transportation services.

As an example, three critical transportation conduits, the Colonial, Plantation and Capline pipelines, were knocked out by a power outage caused by Hurricane Katrina. The pipelines were shut down for two full days and operated at reduced power for about two weeks. These pipelines bring more than 125 million gallons of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel to the northeast seaboard each day. As a result of the energy failure, fuel shortages and price spikes resulted, affecting the transportation network (money.cnn.com/2005/09/01/news/economy/pipeline/index.htm). Gasoline price spiked as much as 40 cents per gallon (or about 25% in September 2005) and aircraft were in danger of being grounded for lack of fuel. In addition to the power outage, Katrina also caused damage to crude oil pipelines and refineries that reduced oil production by 19 percent for the year. Katrina also disrupted Mississippi River exports of the grain harvest. The South Louisiana port is the largest in the U.S. in terms of volume, generally due to grain movements; and there is no economically viable way to export the grain without this port. During Katrina, navigation down the Mississippi was disrupted by sunken vessels, electrical outages, and damage to port facilities. The timing was also of great concern: the perishable exports require transport by the early fall or spoilage can occur. Fortunately, the Coast Guard was able to clear the channels, power was restored, and the grain shipments were transported after significant delays of several weeks (http://text.lsuagcenter.com/en/communications/publications/gmag/Archive/2006/fall/Katrina+Disrupts+Mississippi+River+Grain+Transportation.htm).

Communications infrastructure also plays a crucial role in transportation and energy infrastructure and services. Houston TranStar provides multi-agency management of the region’s transportation system as well as a primary resource from which to respond to incidents and emergencies. Its many transportation management services, including 730 closed circuit television cameras for road surveillance, dynamic messaging systems, centralized traffic management and accident communications systems, and synchronized traffic signals, depend heavily on advanced communications technology and electrical power (http://www.houstontranstar.org/about_transtar/). TranStar has also served as the “nerve center” of emergency management during the hurricanes. After Hurricane Ike, 2,200 of Houston’s 2,400 traffic signals were dark and took almost three weeks to return to full operation. During Hurricane Rita, TranStar’s website was accessed 14 million times during the event for up to the minute information on evacuation routes and shelters, which overwhelmed the communication service as about 2.5 to 3 million people attempted to evacuate. Evacuation routes were jammed and numerous deficiencies were identified. As a result, TranStar’s web services have been upgraded, creating a redundant server in Arizona in case the Houston facility loses power, more wireless “hurricane-proof” cameras have been installed, and TranStar’s coverage area was expanded beyond Houston’s borders (http://www.houstontranstar.org/about_transtar/docs/Annual_2005_TranStar.pdf).

These examples demonstrate the interconnectedness of the transportation-energy and communications infrastructures and their joint vulnerabilities to extreme weather events. A failure to any of these interdependent systems can make a natural disaster much worse. It also shows the far-reaching impacts of such a failure.

2) HOW “URBAN SYSTEMS” ARE DEFINED

This report is particularly co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Series Page

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Background

- Chapter 3 Framing Climate Change Implications for Infrastructures and Urban System

- Chapter 4 Urban Systems as Place-Based Foci for Infrastructure Interactions

- Chapter 5 Implications for Future Risk Management Strategies

- Chapter 6 Knowledge, Uncertainties, and Research Gaps

- Chapter 7 Developing A Self-Sustained Continuing Capacity for Monitoring, Evaluation, and Informing Decisions

- Appendix A Adaptive Water Infrastructure Planning

- References