- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ecology and Religion

About this book

From the Psalms in the Bible to the sacred rivers in Hinduism, the natural world has been integral to the world's religions. John Grim and Mary Evelyn Tucker contend that today's growing environmental challenges make the relationship ever more vital.

This primer explores the history of religious traditions and the environment, illustrating how religious teachings and practices both promoted and at times subverted sustainability. Subsequent chapters examine the emergence of religious ecology, as views of nature changed in religious traditions and the ecological sciences. Yet the authors argue that religion and ecology are not the province of institutions or disciplines alone. They describe four fundamental aspects of religious life: orienting, grounding, nurturing, and transforming. Readers then see how these phenomena are experienced in a Native American religion, Orthodox Christianity, Confucianism, and Hinduism.

Ultimately, Grim and Tucker argue that the engagement of religious communities is necessary if humanity is to sustain itself and the planet. Students of environmental ethics, theology and ecology, world religions, and environmental studies will receive a solid grounding in the burgeoning field of religious ecology.

This primer explores the history of religious traditions and the environment, illustrating how religious teachings and practices both promoted and at times subverted sustainability. Subsequent chapters examine the emergence of religious ecology, as views of nature changed in religious traditions and the ecological sciences. Yet the authors argue that religion and ecology are not the province of institutions or disciplines alone. They describe four fundamental aspects of religious life: orienting, grounding, nurturing, and transforming. Readers then see how these phenomena are experienced in a Native American religion, Orthodox Christianity, Confucianism, and Hinduism.

Ultimately, Grim and Tucker argue that the engagement of religious communities is necessary if humanity is to sustain itself and the planet. Students of environmental ethics, theology and ecology, world religions, and environmental studies will receive a solid grounding in the burgeoning field of religious ecology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Problems and Promise of Religions: Limiting and Liberating

Contrasting Characteristics of Religions

What might be the contribution of religions to the long-term flourishing of the Earth community? If Earth’s life support systems are critically endangered, as the Millennium Ecosystems Assessment Report suggests; if climate change is diminishing the prospect of a sustainable future, as the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change observes; and if species are going extinct, as the Convention on Biodiversity notes, should not religions be engaged?1 How might religions contribute to our present search for creating mutually enhancing human–Earth relations? What of their problems and their promise matter in an era when humans have so radically changed the face of the planet that geologists call our period the anthropocene?2

It is important to ask at the outset where the religions have been on environmental issues and why they have been so late to participate in solutions to ecological challenges. Have issues of personal salvation superseded all others? Have divine–human relations been primary? Have anthropocentric ethics been all-consuming? Has the material world of nature been devalued by religion? Does the search for otherworldly rewards override commitment to this world? Did the religions simply surrender their natural theologies and concerns with exploring purpose in nature to positivistic scientific cosmologies? In beginning to address these questions, we still have not exhausted all the reasons for religions’ lack of attention to the environmental crisis. Although the reasons may not be readily apparent, they clearly require further exploration and explanation. It may well be the case that the combined power of science, technology, economic growth, and modernization has overshadowed traditional connections to nature in the world religions.

Examples from the past and present make clear that religions have both conservative and progressive dimensions; that is, they can be both limiting and liberating. They can be dogmatic, intolerant, hierarchical, and patriarchal. Or they can demonstrate liberating and progressive elements through compassion, justice, and inclusivity. They can be oriented to both otherworldly and this-worldly concerns—escaping into pursuit of the afterlife or affirming life on Earth.3 They can be politically engaged or intentionally disengaged, illustrating the complex and contested nature of religion itself. They may invoke a higher spiritual power while still wielding immense political influence. Religious leaders may preach simple living while their institutions have significant material wealth. The nature of religion is complex and often ambiguous, especially in its institutional forms. Moreover, human failings have often led to disillusionment with religions. It is abundantly evident that religious leaders and followers have not always lived up to their highest aspirations.

However, in examining the varied characteristics of religions as liberating and limiting, both historically and at present, one observes that these characteristics are often more dynamically interwoven than rigidly separate. For example, being bound by tradition, religions have been the source of dogmatism and rigidity. They may favor orthodox interpretations of beliefs and practices. On the other hand, they can show flexibility and transformation over time, as with the Reformation in the sixteenth century that gave rise to Protestantism or with Vatican Council II that occasioned deep institutional changes in the Roman Catholic Church. The ambivalence of religions toward modernity has led to both the resistance and the embrace of change. Such resistance has contributed to the rise of contemporary fundamentalism in many parts of the world. Thus, some religious practitioners reject changing social and sexual values. However, openness to change has caused some traditions to advocate justice for the poor and oppressed, as in the work of Catholic Relief Services, World Vision, Buddhist Tzu Chi, and Green Crescent.4

Many adherents of religions have become embroiled in intolerant and exclusive claims to truth. Sometimes this has given rise to violence or religious wars, as in the Crusades from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries and the Thirty Years’ War in Europe (1618–1648). At the same time, religious traditions have taught peace, love, and forgiveness, even though imperfectly realized. The New York–based organizations Religions for Peace and the Temple of Understanding have been committed for more than 40 years to promoting peace through religious cooperation and dialogue.5 The particularist claims to truth in the Abrahamic traditions have contributed to conflicts between Jews, Christians, and Muslims historically and at present. Although intolerance is not absent in East Asia, exclusive truth claims are rare because interaction and syncretism between religions are so common. For example, in Ming China (1368–1644) the phrase “the three traditions are one” was used to describe the mutually enhancing syncretism of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. This idea extends into the contemporary period across East Asia. In modern Japan one comes of age with a Shinto ritual, practices Confucian ethics in the family and society throughout one’s life, and is buried with a Buddhist funeral.6

Although most religions have been hierarchical and patriarchal, in the last century they have been increasingly responsive to demands for equity, fairness, and justice. Much more still needs to be done for full inclusivity with regard to issues of race, gender, and sexual orientation. This is especially the case with religious teachings in certain traditions regarding women’s roles and reproductive health. However, the expansion of human and civil rights has been an achievement of the last one hundred years, spurred by both secular and religious concepts of justice. Religions have been able to effect change as they participated in this expansion. Now the challenge is to extend this sense of responsibility and inclusivity not only to other humans but also to nature itself.

Religions are often seen as having otherworldly preoccupations, namely concern with salvation in heaven or in an afterlife. Using this logic, some would argue that exploitative treatment of the world is insignificant. These religious practitioners even suggest that degrading the environment hastens the end of Earth and the return of a transcendent paradise.7 Other religious groups have actively denied the critical nature of environmental problems or rejected the science of climate change.

However, most religions value this world and have rituals that weave humans into the rhythm of natural cycles. This is a dimension of what we would describe as religious ecology. The incarnational and sacramental dimensions of various religions illustrate this-worldly emphases and concerns. That is, Christianity centers on a belief of divine entry into material reality both in the historical person of Jesus and in the Cosmic Christ embedded in the universe. Hinduism has a similar understanding with the idea of avatar in figures such as Krishna, an incarnation of the supreme deity, Vishnu. Confucianism and Daoism in East Asia have a strong affirmation of this world, for example in the metaphysics and practices of ch’i (qi), or life force.8 Ch’i is cultivated in the body movements of t’ai chi (taiji) and chigong (qigong) and in the healing practices of traditional Chinese medicine. Most religious traditions have developed sacramental sensibilities in which material reality mediates the sacred. This is evident in the use of water for baptism and oil for anointing the sick. Moreover, offering food and flowers and lighting incense and candles are widespread sacramental practices in the world religions. Such affirmation of material reality is a critical component of our valuing nature.

The role of religion in relation to political power is complicated and highly contested. Religions have often been invoked for destructive or grandiose political ends. During World War II, the Japanese government used Shinto to legitimize their nationalist ideology and the sacrifice of kamikaze pilots. Similarly, after years of severe persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church, Stalin called on ecclesiastical authorities to support the “Great Patriotic War” against Germany. Religions themselves have wielded political power for less than noble ends and often with violent results. This is evident historically in religious wars and with various fundamentalisms present in the world today. The role of politically conservative Christians has been especially pronounced.9 The Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is influential in India, as is the Likud Party in Israel.10

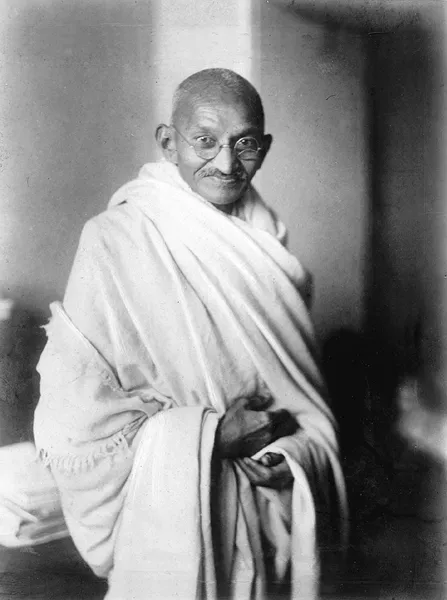

Yet we can also invoke the powerful examples of nonviolent change, as with Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), who was influenced by the Sermon on the Mount. Tolstoy understood the Christian imperative to live more simply as a call to a personal asceticism, particularly for the affluent. In addition, Tolstoy’s pacifism and nonviolence were inspired by a desire for peace as he understood the Gospels. In this quest, his influence extended to Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) (figure 1.1) and Martin Luther King (1929–1968). Gandhi also drew on the Bhagavad Gita in Hinduism, on ahimsa in Jainism, and on the Christian Gospels for his understanding of nonviolence. Similarly, Martin Luther King studied Gandhi, as well as the Christian tradition, in developing his own form of nonviolence. Both Gandhi and King were able to effect political and social change with the spiritual power of their convictions and with the example of their own lives when confronted with violence, hate, and derision. Demonstrations of nonviolent protests were evident in 2011 with the “Arab Spring” and the “Occupy” movement, which highlighted alienation caused by lack of political voice and striking social and economic inequities around the world. Both of these movements manifest the fluid and hybrid character of nonviolent action.

Moreover, there is an emerging movement of religious communities who are participating in transformative social change based on principles of environmental justice. For example, the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice published the first statement on environmental justice in 1987, called Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States.11 The Sierra Club has documented many of these efforts in a report called Environmental Justice and Community Partners.12 They are trying to assist in the creation of new attitudes and practices for the flourishing of the Earth community. This is the challenge to which world religions can make a constructive contribution along with environmentalists and secular humanists working toward a sustainable future.

Figure 1.1 Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948); © Copyright GandhiServe

Many people outside the institutional religions share moral values and spiritual attitudes toward the environment. This includes a broad range of environmentalists, nature writers, artists, musicians, secular humanists, and others. Such values and attitudes are more common than has been previously recognized. Indeed, E. O. Wilson and Stephen Kellert claim that biophilia, or affiliation with the natural world and its biodiversity, is intrinsic to humans.13

In summary, we need to acknowledge the problems and the promise of religions as their perspectives and values are integrated into the academic field of environmental studies and the public force of environmentalism. Within academia it is becoming clear that cultural, ethical, and religious worldviews must be included in the study of environmental issues. This is because historically religions have had ecological dimensions in the ways they ground human communities in the rhythms of nature. This is what we are calling religious ecology. An understanding of the roles of religious ecologies is resurfacing with some intensity in an era when religions were thought to be diminishing with the rise of secularization.

The Persistence of Religions

This brief overview of the problems and promise of religion brings us to a consideration of its persistence in the modern period despite the apparent secularization of Western societies. After World War II, secular humanism grew in Western Europe along with the philosophies of existentialism, postmodernism, and deconstruction. Religions were perceived to be ideological, outdated, ineffective, or oppressive. In short, many came to feel that the deleterious aspects of religions had surpassed their achievements. Moreover, there was a widespread assumption among some European and American academics that religions would wither away as modernity brought the benefits of intellectual enlightenment, economic growth, and technological progress.14 Rationality would replace religion; God was proclaimed to be dead.15 In this view, sociologists of religion predicted both rejection of religions in secular societies and adaptation by the religions themselves to secularization.16 This was influenced by Max Weber (1864–1920), who recognized the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. Our Journey into Religion and Ecology

- 1. Problems and Promise of Religions: Limiting and Liberating

- 2. The Nature of Religious Ecology: Orienting, Grounding, Nurturing, Transforming

- 3. Religious Ecology and Views of Nature in the West

- 4. Ecology, Conservation, and Ethics

- 5. Emergence of the Field of Religion and Ecology

- 6. Christianity as Orienting to the Cosmos

- 7. Confucianism as Grounding in Community

- 8. Indigenous Traditions and the Nurturing Powers of Nature

- 9. Hinduism and the Transforming Affect of Devotion

- 10. Building on Interreligious Dialogue: Toward a Global Ethics

- Epilogue. Challenges Ahead: Creating Ecological Cultures

- Questions for Discussion

- Glossary

- Appendix A: Common Declaration of Pope John Paul II and the Ecumenical Patriarch His Holiness Bartholomew I

- Appendix B: Influence of Traditional Chinese Wisdom of Eco Care on Westerners

- Appendix C: Selections from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007

- Appendix D: Save the Fraser Declaration

- Appendix E: Yamuna River Declaration Resulting from the Workshop “Yamuna River: A Confluence of Waters, a Crisis of Need”

- Appendix F: The Earth Charter, 2000

- Appendix G: Online Resources for Religious Ecology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ecology and Religion by John Grim,Mary Evelyn Tucker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Ethics & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.