Chapter 1 | Setting a Precedent

![Man running on the trail around Mount Trashmore, Virginia Beach, Virginia. (DN)]](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/3284115/images/2356-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 1-1: A pair of the smaller towers at Gas Works Park frame a view of the PlayBarn.

Adaptive reuse in architecture—the complete transformation of a building, in terms of its function—has been a common practice in the United States since the historic preservation movement took root in the late 1960s. Train stations became restaurants, movie theaters were turned into churches (and vice versa), while just about anything that could be converted into a house often was, from tugboats to wine barrels. The process can be seen as recycling, since it forestalls the destruction of an object by providing it with a new, second life.

Similarly, there are a multitude of abandoned toxic properties around the country, found in beautiful settings, like old mines along mountainsides and industrially marked riversides. Those who choose to tackle the reclamation of these landscapes, as well as empty buildings, are able to take advantage of what has become a well-established culture of historic preservation in America. The federal government has made things work more smoothly in the past two decades through such legislation as the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act. As passed in 1991, ISTEA (pronounced like the beverage) was targeted to assist in the reuse of transit-related, commercial projects, but its scope was gradually expanded. Prior to that time, adaptive reuse projects tended to be seen as involving considerable financial risk. Success stories among the early trailblazing attempts prove quite inspiring as a result.

Gas Works Park in Seattle, Washington

The story of Gas Works Park is something of an environmental parable. Portions of it come straight out of the fairytale canon, in a most unlikely setting. The chain of events in Seattle was a bit fantastic, even though grounded in reality.

Landscape architect Richard Haag, along with a few colleagues, saw and pursued a vision of taking the abandoned Seattle Gas Company facilities—located on one of the most wonderful, but also most contaminated, sites in the city—and salvaging from this leftover one of America’s most inventive urban parks. From the start, Haag had a sense he was in for a bit of a wild ride with the project: “It was a Cinderella rich in industrial residues and toxic hydrocarbons.” Seen as a fable, the path to redemption was naturally difficult, strewn with obstacles and many skies of gray (this being Seattle after all), but with perseverance beyond that of mere mortals, the hero triumphs. In real life, Rich Haag may have felt more like Don Quixote tilting at windmills all too often, but the plotline does fit neatly with the mythos of Seattle.

Like anywhere else in the country, the Pacific Northwest has its pluses and minuses. From top to bottom, there are the magisterial views in every direction, balanced by a climate that taxes the patience of even the locals. With all its rainy days, ultramodern Seattle faces a constant battle not to be overgrown by Mother Nature. The city trades on its nickname, “The Emerald City,” as it did when it hosted the 1995 NCAA Men’s Basketball Final Four. A few of the main thoroughfares around the Kingdome—the principal sporting venue in the city at the time—were painted a bright yellow in a play on the theme “Follow the yellow brick road.” Seattle’s real magic kingdom, of plants and otherwise, turned out to be Gas Works Park.

Rich Haag’s signal accomplishment at the site was to marry biophytoremediation—a “regreening” process involving removal of toxic substances via living organisms like soil microbes and plants—with adaptive reuse, saving what he could of the old gasification plant in the process. When Haag unveiled his Master Plan for a new park in 1971, phrases like “urban archaeology” and “brownfield reclamation” had yet to be coined. By the time Gas Works Park opened in 1975, not only was it a leap of faith for Seattle, it was a forerunner on the urban scene as well, one for which Richard Haag has since been justly celebrated.

Along the way, it was no picnic ground. The site was nearly bulldozed, as plans conflicting with those of Haag called for the land to be scraped clean of its industrial past to make way for an exclusive high-rise housing estate. In 1972, the standing, entirely unsympathetic Mayor of Seattle offered to be the first one there, with a blow torch, to cut down the old gas plant. Instead, the plans held to retain the 20-acre site as a public park. The industrial remnants that could not be saved and adapted were piled up to form Earth Mound, a kite-flying hill with unobstructed views of downtown Seattle to the south. For city residents this all came as a bonus, representing a second chance for a site that had been lauded as special about seven decades earlier by the Olmsted brothers, America’s urban park pioneers.

The History of the Site

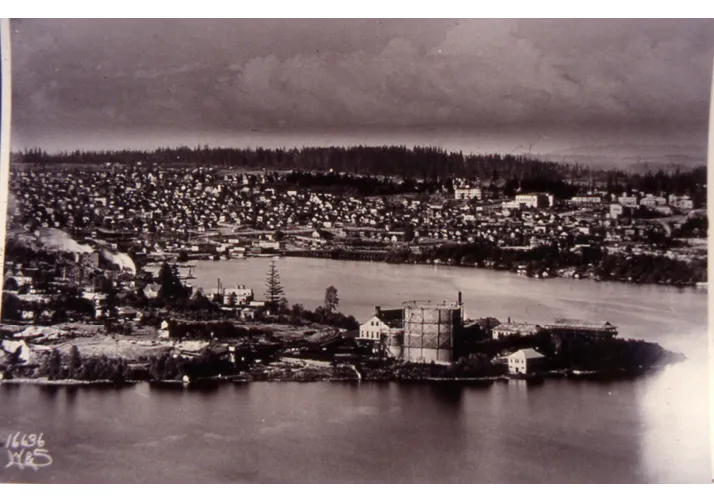

Figure 1-2: Early gasworks view, c. 1930. (RHA Archive)

In 1906, the Seattle Light Company built a major coal gasification plant on what Richard Haag now refers to as “a prow of land,” its curving shoreline projecting roughly four hundred feet into Lake Union from its northern boundary. At that time, according to Haag, “Lake Union was hardly a lake, more of a swamp.” Back before the first white settlement was established at Alki Point in 1851, it was a portage way for those in the area making their way from the inland lakes to the saltwater sound. Lake Union only took its current shape in 1917, with the completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal to the east and Ballard Locks to the west. With these waterways opened, unifying Lake Washington with Puget Sound, Lake Union fulfilled its nominal role.

The lakeside manufacturing plant, designed to burn coal and produce “illuminating gas,” was one of four such facilities in Seattle, among what Haag estimates as “15,000 in the United States—and the last to close.” As a wry historical footnote, even as the gas plant was being planned for the site, there was some public discussion that this plot of land might best be used as a public park. The talk was prompted by a report from America’s foremost landscape architects. The Olmsted brothers were based in Brookline, Massachusetts, but were influential from coast to coast. Frederick Law Olmsted, the chief designer for Central Park in New York City, concurred with his brother’s opinion of the lake site, after John Charles Olmsted paid a visit to Seattle in 1906. He was scouting the newly relocated campus for the University of Washington. Only a mile from Lake Union, the site had been temporarily set aside as the fairground location for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. During his visit, Olmsted made note of the land where Seattle Lighting was about to build: “It should be secured as a local park because of its advantages for commanding views over the lake, and for hiking, and for a playground.” The view was prophetic, though it would have been impossible to foresee the rocky road ahead for the site.

Figure 1-3: Gas Works Park aerial photo, 2011. (Patrick Waddell)

The gas works processes underwent substantial changes during the half-century the plant was in operation. After thirty years of burning coal, hauled to the site by boat and train, the plant was expanded to burn oil. The change was made when it became possible for oil tankers to reach Lake Union in 1937, to fuel the machinery of the newly renamed Seattle Gas Company. Two decades later, the City of Seattle made its own official conversion, to natural gas. Suddenly, in 1956, the plant was out of business. The shutdown was absolute, leaving the gas company with an obsolete facility on a very prominent piece of land.

The Park Narrative

Richard Haag had moved to Seattle in 1958 to establish a landscape architecture program at the University of Washington from the ground up. As he began to develop a design project in 1963, he was already aware of the abandoned gas works. A student employee of his, Frank James, lived in a houseboat along the eastern edge of Lake Union—much like the one occupied by the Tom Hanks character in the film Sleepless in Seattle. In those early years after the Seattle Gas Company closed its operations, the northern perimeter of the gas works property was fenced off from the public. From the lakeside, however, access was unimpeded. James ferried Haag across the lake for his first visit to the site. In retrospect, the genie was now out of the bottle.

The design project Haag had set for his current crop of students morphed into a much broader event. For what had become an impromptu national design competition, he “packaged topos and aerial and eye-level photographs of the ghostly gasworks” and submitted this as the Landscape Architectural Exchange Program to 130 junior-level students. At the time there were only a dozen landscape programs accredited in the country. Among the entries submitted, Haag was unsurprised to find about ten variations on the Sydney Opera House competition winner, each of these projects mimicking the formal fireworks of the future icon, just then planned for Bennelong Point in Australia. Other proposals for the gas works site included a few zoos and some college campus layouts. In retrospect, Haag is bemused that “not one student in one proposal saved anything on the site. It was scorched earth.” He hangs his head to this day that he himself did not immediately see an alternative: “I accepted their collective ‘pillaging’ without protest.”

By 1970, when Richard Haag was first approached professionally to design a public park for the site, he still lacked a clear vision for the project: “I brought with me all the baggage and preconceptions of most architects.” He found his answer in his own teaching methods: “I had been telling my landscape students that you must spend a night on your site. So I’d sleep out among those gas works buildings. I haunted the buildings.” Haag’s epiphany, now related smilingly, came with finally gaining recognition of just what were the principal elements of this site: “I thought, ‘Wait a minute! Where is my forest? Where are my outcroppings? What are the most sacred things on the site?’ It has to be the towers.” Indeed, those towers comprised Richard Haag’s own private Stonehenge on those lonely nights. Saving these remnants of the gasification plant became a matter of utmost importance: “This vanishing species of the industrial revolution was to be saved from extinction through adaptive reuse.” In the struggle to retain the rusting leftovers from the gas company, Haag kept his focus on the 68-foot-tall towers as the key to the park plan: “It goes to scale, to monumentality.”

“Do Not Eat the Soil!”

A chemically-poisoned wasteland, covered by an assortment of decayed industrial hulks, is hardly the typical starting point for a public park. A newspaper editorial in 1971 ridiculed the master plan for the park: “It would be like trying to build a cake on the moon.” Looking back from 1978, with the park already a reality, Sally Woodbridge, writing in Progressive Architecture, marveled at the change to what she termed “a gigantic walk-through Tinker Toy,” from its previous incarnation as “an industrial sink.”

Even as the City Council unanimously approved the master plan for the park in 1971, there remained a steady flow of opposition on various political and scientific grounds. The bioremediation processes proposed for the site were largely untested at the time, while other challenges presented by the site seemed endless. Among early recourses was a move to close down the twenty-seven outflow pipes projecting out into the lake. According to Haag, the gas works remnants themselves presented serious problems: “The iron structures were often rotten and rusted—the mild sulphuric content of rain in the Northwest tends to corrode metal buildings.”

Above all, the land upon which all the buildings rested was the primary concern. With the sale of the works to the City, the deed said “the gas company must remove all structures down to grade.” Haag raised the question whether this required going back to the original 1906 grade or to the present grade, built up by a half-century of dumping. Ultimately, Haag saw past this matter, finding a way to save work on all sides: “We said, ‘Let’s go to the City and strike this removal clause.’ This enabled us to save the structures.” In letting the gas company off the hook, as far as cost and efforts of removal, Haag was taking a gamble that the bioremediation would be effective, allowing both the site and structures to remain intact. He saw reason to hope even before work began. Clearly, the site was polluted, but he noticed that the Northwest’s typically intrusive pairing of alders and wild blackberries were present around the lakefront perimeter. Still, this symbiotic duo did not penetrate to the interior of the toxic site. “Active reclamation” was necessary.

To salvage the property, Richard Haag assembled a team of like-minded consultants. Foremost among them was Richard Brooks: “He was a master, a brilliant chemist and a believer in the natural processes.” Brooks was fully prepared to explore the prospects of biophytoremediation, but knew to follow protocol first. He brought in environmental experts and oil company specialists, taking full account of a mix of the resultant, very expensive, proposals to detoxify and to handle the hydrocarbon-based pollutants. Most toxic was the benzene. One soil specialist proposed that they run steam pipes from under the lake to heat the ground until the pollutants percolated out. The price tag was $800,000. (By contrast, the entire budget for the park at that time was barely twice that figure—that amount possible thanks to a Forward Thrust Bond issue of $1,617,000 approved in 1968.)

Personal philosophies, as much as economic realities, led Haag and Brooks to follow a more natural path: “We set about developing bacteria that could digest hydrocarbons as a food source.” The men had a colleague, known by the name Labos, who told them, “The best bacteria are right under our feet. They started mutating here on site, when the first shovelfuls of coal arrived.” Like a doctor understanding the capacity of the human body to heal itself, the consultants knew that the soil, any soil, can contain its own defenses and its own seeds for renewal. Some help was still required to allow the remedies to take root: “The process involved breaking up the crust of the old oil spills. We needed compost to keep it more friable. Sawdust, too. At that time, Seattle was dumping collected sawdust on Indian tidelands. We took it all, even diverted waste limbs from city parks, to add to our sawdust piles.” In this way, with a measure of poetic justice, a portion of some of the old...