eBook - ePub

Prêt-à-Porter, Paris and Women

A Cultural Study of French Readymade Fashion, 1945-68

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the first critical history of French ready-made fashion, Alexis Romano examines an array of cultural sources, including surviving garments, fashion magazines, film, photography and interviews, to weave together previously disparate historical narratives. The resulting volume – Prêt-à-Porter: Paris and Women – situates the ready-made in wider cultural discourses of art, design, urbanism, technology and international policy.

Through a close study of fashion magazines, including Vogue and Elle, Romano reveals how the French ready-made and the genre of fashion photography in France developed in tandem. Analyses of representations of space, women and prêt-à-porter in such magazines – alongside other cultural ephemera such as contemporary film, documentary photography and family photographs – demonstrate that popular conceptions of fashion and modernity shifted in the period 1945-68.

By connecting national and personal histories, Prêt-à-Porter: Paris and Women reveals the importance of the ready-made to broader narratives of postwar reconstruction, national identity, gender and international dialogue.

Through a close study of fashion magazines, including Vogue and Elle, Romano reveals how the French ready-made and the genre of fashion photography in France developed in tandem. Analyses of representations of space, women and prêt-à-porter in such magazines – alongside other cultural ephemera such as contemporary film, documentary photography and family photographs – demonstrate that popular conceptions of fashion and modernity shifted in the period 1945-68.

By connecting national and personal histories, Prêt-à-Porter: Paris and Women reveals the importance of the ready-made to broader narratives of postwar reconstruction, national identity, gender and international dialogue.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prêt-à-Porter, Paris and Women by Alexis Romano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Accessing the everyday: Prêt-à-porter, Paris and women in magazines, 1945–65

The first issue of French fashion and lifestyle weekly Elle, published in November 1945, effectively set the tone for the magazine’s successive publication. Its first photograph pictured a close-up view of a model, standing in almost full length, posed with one hand behind her jacket by couturier Lucien Lelong and the other on the iron railing of a balcony (Figure 1.1). This elevated position in Paris offered an iconic view of the Seine with one of the city’s bridges in the background. Her stance and direct eye contact with the camera engaged the reader in a dialogue, expanded on in text. The intimate relationship between magazine and reader was thus fundamental from the outset. Readers became conflated with the publication itself, ‘elle’: a universal ‘she,’ but more particularly, the elegant Parisian woman. The article’s summation of ‘new elegance,’ based on ‘choos[ing] what works for you’ instead of ‘blindly follow[ing] fashion,’ offered a noticeably novel tone and construction of fashionability based on an active and independent, yet still feminine woman.1 As such the magazine sought to break from the past and launch a post-war and modern dialogue; one that foreshadowed the ideological landscape of the 1950s, in its constant vacillation between new and old.

A product of the post-war period, Elle’s development closely tied in with contemporary national issues and attitudes. It filled the place of middle-range Marie-Claire, which had been suspended after the war,2 and fell between glossy, expensive magazines such as Vogue, La Femme Chic, Femina and Album du Figaro, and mainly small-format feminine lifestyle magazines in the style of Je m’habille, Modes de Saison, Modes et Travaux, Modes de Paris, Femme et la Vie and Le Bonheur à la Maison.3 Fashion was featured in these latter magazines in one or several-page editorial format, to purchase as patterns or mail-order garments, often accompanied with one or more pages of haute couture imagery. On similarly rough newsprint paper, Elle too featured stories, advice columns, recipes and reports. Yet a fresh tone set it apart in 1945. The above text clearly distinguished the present from a past moment: ‘For women the past few years was a sad age of uniformity. Long live femininity! Long live personality!’4 Fashion magazine language is commonly conceived around the notion of novelty, but here, set against the context of great national changes, notably the Liberation and women’s suffrage, language assumed compelling meaning. This new discourse began to penetrate the symbolic construction of fashion that had traditionally relied on the visual interchange between Paris, women and haute couture.

Figure 1.1 Ensemble by Lucien Lelong. Elle, 21 November 1945 © ELLE FRANCE

From the early 1950s and into the 1960s, the feminine press, led by Elle, gradually steered its discussion towards readymade dress, featuring this production more predominately than haute couture or clothing patterns. Editor-in-chief Hélène Lazareff created the magazine after spending the war period in the United States working for Harper’s Bazaar.5 During this time she would have observed the considerable advances in the American sportswear industry. Although Elle first photographed readymade garments in 1948, it and other magazines were forbidden from identifying their manufacturers.6 These regulations changed around 1950, at which point Elle featured rare readymade editorials with named makers. This development was due largely to the work of fashion editor Annie Rivemale and her assistant Claude Brouet, who recalled her expansion of the readymade clothing division on her arrival in 1953: ‘I was very passionate. […] I started the prêt-à-porter section in Elle. […] In the beginning I had a small file with some sketches of the best garments then afterwards it became a wardrobe.’7 Although French Vogue, first published in 1920, stood for older ideals of elite fashion, it created a regular section on readymade dress in 1952. Another established fashion periodical, Jardin des Modes, had already taken this step in 1951.8 From about 1954 the pages of the press presented it to a perceptibly greater extent, which coincided with the arrival of a group of women in the fashion press: Edmonde Charles-Roux became editor of Vogue in 1954, and Maimé Arnodin shaped Jardin des Modes between 1951 and 1958, along with its future editor Marie-José Lépicard from 1957. Brouet, who became Elle’s fashion editor in 1965, preferred to feature readymade production because although couture ‘could be very beautiful, ideas that were very new and adaptable to the life of everyone weren’t coming from there.’9 Female professionalism in the press can be seen to have direct ties to the presentation of more practical, accessible garments. This new content, as well as the press’s informative and less autocratic relationship to readers in the mid-1950s, constituted ‘a fundamental transformation of its relationship to fashion,’ according to Stéphane Wargnier.10 By the late 1950s, magazines were tools of mass visual communication that disseminated a cohesive fashion message to shape collective consumer identity.11 Their new direction accompanied the work of manufacturers who, from the early 1950s, took steps to modernize and improve production and the image of the industry, as the following chapter discusses.

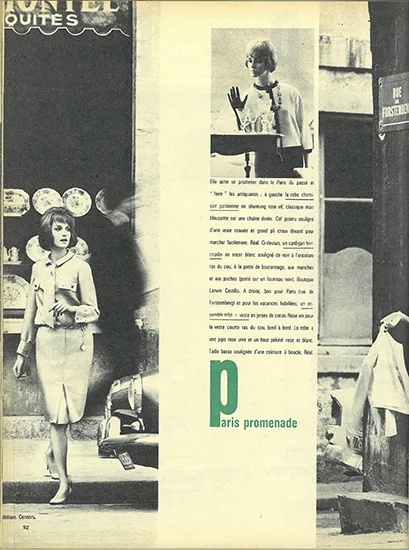

Modernity was a fraught concept in post-war France, in the throes of modernization – of its design industry and cityscapes, and in the lives of its newly enfranchised women citizens. The press’s presentation of readymade clothing reflected this tension, as illustrated by ‘Paris Promenade,’ a 1961 Elle editorial. Text captured the nostalgic mood of William Connors’s photographs of models, explaining, ‘She likes to stroll in the Paris of the past and “browse” the antiques.’12 Photography’s rise in French fashion magazines coincided with post-war renovations of the city, giving meaning to Susan Sontag’s observation that ‘a device is available to record what is disappearing.’13 The presentation of industrially produced readymade clothing in the press seemed to spur the need for such visual documentation of ‘Paris of the past.’14 Yet it was also visualized in ways that spoke to the changes taking place. For, in contrast to the model pictured in the upper right section of the page who peered at the antique glasses within a shop, the image at the bottom left depicted a woman with an outward gaze stepping into the street (Figure 1.2). This model walked away from the relics of French design, symbolized by porcelain tableware in the shop window; she looked to the present and not the past, to the freedom offered by the street and not the encapsulation of the interior, or photography studio. But she did not leave Paris, rather, her pink shantung shirtdress, or ‘robe chemisier parisienne’15 marked her as unquestionably Parisian. From the late 1950s, the fashion press abounded in images of shirtdresses, unfitted dresses typically with button closure to resemble a tailored blouse. Here, the author described the garment as ‘classique,’ but pointed out its novelty, made to look like a separate blouse and skirt with the addition of a gilt chain. Likewise, the dress, woman, automobile and the blurred presence of a hurried passer-by in the photograph became expressions of urban modernity when pictured against the architecture of nineteenth-century Paris.

This chapter explores the relationship of Paris, women and readymade dress as images and constructions in Elle and Vogue, in the context of modernization and changes in women’s lives. It considers the twenty years following women’s suffrage, and traces shifts in imagery as seen, for example, between Figure 1.1, an image of a protected woman above the iconic city, and Figure 1.2, where she is situated in the midst of action. That these shifts took place in tandem with the growth of photography in French fashion magazines is significant. Alongside its main aims, this chapter traces developments in image technology, from illustrations and photography to moving imagery and relates the production of image to the construction of fashion and ways of seeing.

The first section draws on symbolic production theories to establish how readymade dress, epitome of practical clothing for the ‘everyday,’ figured into the elite spaces of magazines’ pages in the decade following 1945 and those of Vogue in particular, in relation to Paris’s hegemonic fashion position. During the 1950s, Henri Lefebvre conceived the second volume of his Critique de la vie quotidienne, published in 1961, which identified the quotidian as a concern of the post-war period, ‘an age such as ours when so many things are changing, but not all and not all in equal measure.’16 Namely, Lefebvre found the everyday to be underdeveloped in relation to industrial production and technology. Disconnected from historicity and the world’s natural cycles amid rapid modernization and capitalism, he contended that everyday life had turned into a place of sheer consumption. As Kristen Ross has underlined, Lefebvre sought to ‘expose’ and critique the quotidian to counter the alienation experienced by individuals in the modern world.17 He also advocated photography for its capability of locating the everyday.18 In connection to these ideas, this chapter considers how readymade dress as image, and the new discourses it drew on, likewise exposed the everyday in ways that both embraced and renounced modernity. Its second section examines various ways Paris was visualized in photographs in the mid-1950s that spoke to the modernization of the industry and city, and to modernism in imagery. It considers bodies that inhabited spaces, and magazines’ discourse of narrative and movement. Lefebvre shared his Marxist critique of capitalism and consumer society with the revolutionary group of artists, intellectuals and political theorists who composed the Situationist International from the late 1950s. They counted among the period’s creative thinkers who endeavoured to interweave artistic production and individual creativity in everyday life and urban interaction. In view of these cultural discourses and environment, section three carries this chapter into the 1960s and explores the intersection of movement, moving image and reality in the press, as the notions of access and autonomy became more of a reality and a problem for French women.

Figure 1.2 Dress sold at Réal. Photograph by William Connors, Elle, 21 April 1961 © William Connors/ELLE FRANCE

Fashion and Paris

Paris had long been associated with luxury trades, sumptuous clothing production and, from the mid-nineteenth century, haute couture. The connection of Paris with fashion was so intrinsic that the cover of the first issue of Vogue published after the Liberation in winter 1945–6 by Simbarakiva pictured an unpopulated, sunny Paris scene, with no allusion to dress. Readers would have nonetheless recognized that well-known view of the city as the Place de la Concorde, a site associated with monuments of French history, government, tourism, as well as fashion, for the city’s main luxury shops were located just north of this square. They might not have been aware, however, that this cover image had been intended for the September 1939 issue of the magazine, which was never published.19 According to then editor Michel de Brunhoff’s assistant Léone Friedrich, ‘All importance was given to blue skies, and to white clouds, and the profile of the square below.’20 The secondary focus placed on the city alluded to its imminent loss, as well as that of the industry, during the German Occupation. Thus, the cover image served to underline the city’s role as a fashion centre and, on another level, showed how this centralization was interwoven in wider national issues. Re-contextualized in 1945, the cover set the tone for the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- A note on the text

- Introduction

- 1 Accessing the everyday: Prêt-à-porter, Paris and women in magazines, 1945–65

- 2 Branding prêt-à-porter in the Fourth Republic (1946–58): Modernization, cultural diplomacy and industry debates

- 3 Displaying industrial modernity in 1950s’ Elle: Readymade dress, rational space and the image of women

- 4 Negotiating the avant-garde in the 1960s: Stylisme, industry debates and restless images

- 5 Expanding the urban fabric in the 1960s: Redefined bodies, dress and city space

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Imprint