eBook - ePub

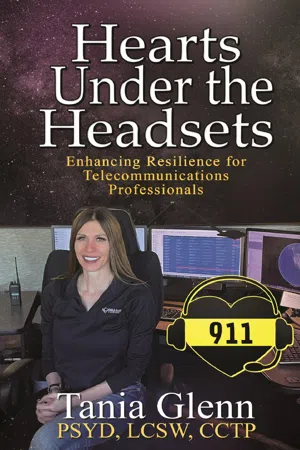

Hearts Under the Headsets

Enhancing Resilience for Telecommunications Professionals

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Communications specialists-our police, fire, and EMS dispatchers and 911 call takers-are some of the most important members of public safety, yet they are frequently some of the least-recognized members of these teams. Communications specialists face some of the same challenges and stressors that public safety members in the field face, but they also have their own set of unique stressors and challenges. Hearts Under the Headsets: Enhancing Resilience for Telecommunications Specialists addresses the hearts and minds of our communications community with a focus on resilience and preparation for what is ahead.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hearts Under the Headsets by Tania Glenn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Communications Specialists Are First Responders

I’m a survivor, come ride with me

Been through hell and back, don’t need your sympathy

Everything I wanted is right in front of me, yeah

I’m a survivor, come ride with me

“Survivor” by Pop Evil

A few years ago, in my home state of Texas, communications specialists—our dispatchers and 911 call takers—were deemed first responders. To be honest, I was shocked to learn that they were not already considered first responders. I have always addressed police, fire, and emergency medical services (EMS), and in my mind, this also meant the communications professionals who work for these departments. Except for proactive patrol in law enforcement, there is no such thing as public safety without the 911 center. It starts with the call to those three lifesaving and utmost important digits on the telephone. Almost nothing happens without dispatchers and call takers.

For the most part, communications specialists have been considered operators or secretaries for quite a while. A look at some very interesting history reveals why communications specialists have not been considered first responders until recently.

On March 13, 1964, in the very early morning hours, New York City resident Kitty Genovese was attacked with a knife and ultimately murdered just a few blocks from her apartment. The attack lasted several minutes, during which Genovese fought for her life and screamed for help. It was reported that multiple people heard her screams and only one man called the police department. That call went unanswered.

This became a widely known and studied case on human behavior, compassion, and callousness. Additionally, this case is considered one of the driving factors for the development of the emergency 911 call system.

Until the late 1960s, if there was an emergency, people would call the nearest police or fire station, or they would call the operator to get connected to the department they needed. By 1968, the 911 number was established. These numbers were chosen because there were only three, and they were easy to remember. Also, the numbers 911 had not been used as an area code yet.

Initially, those answering 911 calls and dispatching emergency services personnel were typically secretaries. They would answer the call and then pass their notes on to the responding agencies. This explains why those in the profession were classified clerical for many years.

Over the years, emergency communications have evolved. The technology, training, and the services these specialists provide over the phone and on the radios has morphed into a very complex job. Throughout the evolution, the role of telecommunicators has become one of providing police officers, firefighters, and EMS with vital information that they need in order to respond effectively and safely. They also direct the public on what to do, based on the information they are getting, until the members of the field arrive.

Still, somehow, our telecommunications professionals have had to fight for their status as first responders. Perhaps it is the fact that they remain in one place versus going to the scene and they do not interact face-to-face with the public. Perhaps it has simply been the “out of sight, out of mind” problem that our communications personnel have faced since the beginning of the profession. Whatever the reason, it is time for all fifty states to recognize our telecommunications professionals as first responders. Simply by looking at what our communications members do day to day, one can see that they are not operators, secretaries, or clerks.

Ask any field personnel to tell you about their favorite dispatcher. They will tell you that this person feeds them vital information without the need to ask for it, they seem to predict what the field first responders need sometimes before they even realize they need it, and they constantly check on their status to assure their safety. If you probe deeper, many members of the field will tell you that their favorite dispatcher was the voice of calm and reason on their worst day or even that this person saved their life.

Ask any dispatcher how they know someone in the field is in trouble and they will describe very intricate details such as the tone of their colleague’s voice, the fact that they keyed up and said nothing or simply the way they keyed up on the radio. The synergy and camaraderie that occur between the field and communications specialists are not only amazing, but also vital to the safety of all personnel. If someone in the field is in trouble, dispatchers stand at the ready to launch the swarm of backup until the situation is stabilized.

In the mid-1990s, a paramedic named Mike was on the ambulance dock at the hospital where I worked as an emergency room social worker at the time. He was restocking his ambulance after a call. His partner was inside the emergency room, completing his paperwork. Just before midnight, a local man with a significant history of mental illness walked up behind Mike and shoved something sharp into his back. The sharp object and the man’s hand were covered by a towel and Mike could not tell what it was. The man demanded to be taken to another hospital.

As Mike and the mentally ill man climbed into the ambulance, Mike hit the emergency transponder on his radio to let his beloved dispatchers know that he was in trouble. The communications team responded right away by checking the status and welfare of the crew. Mike’s partner, who had no idea any of this was going on, told them they were clear. The dispatcher asked them to reset the emergency transponder. After a few seconds that seemed to last a lifetime, Mike’s out-of-breath partner keyed up in complete panic and stated that he was standing on the dock, watching his partner and an unknown occupant drive away in their ambulance.

What ensued next was absolute chaos. This event happened before we had the luxury of the amazing tool known as Global Positioning System, or GPS. This was a time when we still had maps and map books. Communications notified the police department and the rest of the EMS agency immediately. Law enforcement was frantic and so were the rest of the paramedics, many of whom attempted to aid in the search. The problem was that all the ambulances in the same system look identical except for one number on the side and back of the ambulance. It made for a chaotic search for Mike, as ambulances were driving all around looking for him and the police officers were having to figure out that each ambulance they came across was not Mike’s.

Meanwhile, Mike smartly drove his abductor to the next closest hospital. The man, in the passenger seat, aimed the weapon, under the towel, at Mike the entire time as he also threatened to kill him. When Mike turned in toward the emergency room at the new hospital, the man jumped out of the ambulance and disappeared. Mike walked into the ER and called the communications center to let them know where he was and that he was okay. He later found the weapon, a screwdriver, as well as the towel, but the abductor was never identified.

Needless to say, the commander on duty asked me to visit the crew that night. As I was getting dressed, I asked what station I should head to, and the request from Mike and his partner was to meet them at IHOP. I have always maintained that we start intervening in every crisis at the base of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which is food, water, clothing, shelter, and safety. So IHOP it was—where we could add caffeine and sugar to the hierarchy of needs.

Sure enough, when I got to the restaurant, the coffee was flowing, the pancakes were smothered in whipped cream, and the entire restaurant had heard the story. So much for confidentiality. If there is one thing I have learned in thirty years of practice with first responders, it’s to just go with the flow. As I sat down in the booth, the waitress was calling Mike “Sugar” and telling him that his meal was on the house.

Mike, his partner, and I chatted it up for a while. They were both coming off the adrenaline rush, but they were both doing remarkably well. In actuality, they were completely good to go.

We all knew, though, that the dispatchers were probably not as good, given the nature of what happened and the fact they were not having the luxury of an IHOP-infused closure. So, we made a plan. We ordered food for me to take to them, and I asked Mike to give me a thirty-minute head start. I went to the communications center and the team started to spill. They talked about the stress of the event and how worried they were throughout the search for Mike’s ambulance. As we talked and ate, they started to decompress. I normalized their reactions and educated them on what would be ahead for them. As I wrapped up, Mike walked into the communications center, and it felt like Christmas morning. There were hugs, tears, laughter, and more hugs.

This event highlights some very important points. The first and most important is the absolute cohesion and camaraderie that occurs between the field and communications. They are one team, and they impact each other every day. While Mike’s situation resolved itself, the rest of the field and the communications professionals were right there and would have been on top of the situation should it have gone differently. The second point is the fact that our communications personnel are not somehow immune to stress simply because they do not see what is going on. In some cases, it’s worse for them because they cannot jump in and help or because they may not have the same level of closure that the field has. The third point is that with every incident, we must consider, remember, and support our telecommunications professionals. To leave them out is to potentially cripple a very important part of every team.

Finally, it is important to address the investment that communications personnel place in the safety of the members of the field. Many still envision the communications center as a separate entity from the field, which is a mistake. Communications centers are the thread that ties the incident together with the field. The communications specialists link the event and the real-time intelligence to the field so they can safely and properly respond. Communications specialists are just as much a part of the team as anyone else, and they take their role, especially when it comes to protecting the field, very seriously.

In 2014, I responded to a very traumatic helicopter crash. On my fifth and final visit to the city where the crash occurred, twenty-six days after the event, my final job was to do progressive desensitization for the flight nurse involved in the incident, which meant getting back in the aircraft and going for a confidence flight. We were at the base, set to go, when in walked four individuals from the communications center. If looks could kill, I’d be dead. The hostility was palpable. I completely understood that they had no idea who I was and that this nurse was their crew member, not mine.

At some point, the four communications team members went into the hangar for a discussion. I heard one of them saying, “I don’t know who she is, I don’t know who she thinks she is, and I am not sure if I like her.” Clearly my smiles and attempts to engage in small talk were not enough.

When they returned to the crew quarters, I knew I had to win them over. They were standing behind a couch staring at me, so I went over to the couch and, rather than sitting down, I put my knees onto the cushions so that I was kneeling and faced the back of the couch. This had me facing them, lower than they were, which was a total act of submission on my part. I am tall, so approaching them and standing close could potentially be threatening, especially given the angst they had about me. As I knelt below their eye level on the couch, I started talking about peer support. I mentioned that the co...

Table of contents

- The Story Behind the Documentary

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Communications Specialists Are First Responders

- Chapter Two: The Challenges They Face

- Chapter Three: Communications Trauma

- Chapter Four: Solutions

- Chapter Five: The Path Ahead

- About the Author