- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

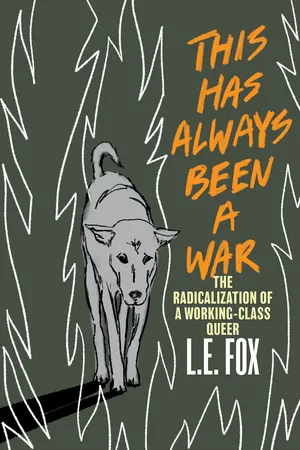

Yes, you can access This Has Always Been a War by Lori Fox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Call You by Your Name

I

Do you remember, Lucky, how fucked up I was when we first met?

Gabrielle had just left me. She’d been sick for months after the car accident, after the concussion; she couldn’t drive or read from a screen, she didn’t know what time it was or how much time had passed even when she looked at a clock, couldn’t keep appointments, couldn’t watch a movie or read a book, couldn’t remember a conversation that happened twenty minutes ago, so I did those things for her: I became not only her lover, but her caretaker, timekeeper, appointment manager, transcriber, personal cook, and assistant.

She became, overnight, a confused and furious stranger with the face of the woman I loved. It changed her forever, and by the time I realized this, I had already resolved to love her, no matter what.

And then she got a little better. And then I took a breath, stepped back for a few weeks to take care of myself, head out into the backcountry.

And then she cheated on me, as carelessly and casually as one might cheat at a game of cards—publicly, sober, in front of all our friends. Like I didn’t even exist.

Watching her struggle, watching her suffer and despair and try to climb back into herself, watching her disappear and reappear and disappear again and again and again, even as I put my own life on hold for months at a time to care for her while she recovered, had put a crack in me so deep down, so far inside myself I didn’t even know it was there. When she cheated on me, that hairline fracture splintered and broke under the pressure of that hurt and humiliation. I didn’t understand, then, that sometimes people do things when they are hurt and hurting and afraid that are not about you at all—sometimes people hurt other people just because they are in pain and afraid and don’t have any other language, any other words, with which to express it.

Had I known that, maybe things would have turned out differently … maybe I would have been able to forgive her sooner, maybe I never would have met you, maybe I wouldn’t be talking to you like this now, six years later. But I didn’t know it.

Something in me broke that wouldn’t heal for years, something essential. I couldn’t stand it, so I ran away. I quit my job and disappeared into the bush with my truck and camper.

There was a good burn south of Watson Lake, and I went out there to make my living picking morels. Nothing seemed left alive in that blackened, harsh country, nothing except the ravens that turned slowly overhead like the rusted cogs of some great, ancient machine. It was good. I needed that place, with the smell of ash always in the air and the endless expanse of destruction and resurrection spreading out forever under the midnight sun. I picked morels all day and I drank all night and then I woke up hungover, had a beer and a couple cups of black coffee, and went out to pick mushrooms again.

Which is where I met you, of course: in the mushroom camps, trying to make your season’s fortune, like everyone else.

I barely remember the first time I met you. I was drinking all the time then, was already on my way down. I think Patricia, my dear friend, my polar opposite, dark-haired and boyishly tall and impossibly feminine, pointed you out to me when I told her what I was looking for as a possible candidate.

I’d seen you around, but I’d never spoken to you before. You were handsome: dark hair, strong jaw, lean and wiry and muscular. You had awful tattoos though, a screaming clown with a lopsided face, words scratched into your forearm as if by a hand that had been shaking. You never wore shoes, so the soles of your feet were black and tough as a strip of rawhide. You had a red-plaid coat full of holes and pockets, from which I had seen you produce an apparently endless supply of Lucky Lager. You had a tattered Lucky Lager T-shirt, too, from some flat of long-since-drunk beer, and you were always trying to get me take pictures of you in it so I could post them to Instagram when we got back within cell service. You were sure one day Lucky Lager would see it and give us a sponsorship, and then we’d be made.

That’s why I started calling you Lucky, remember? You always relied so heavily on luck. It was part of your brand, of the person you wanted people to see you as. I liked that about you. It felt like confidence and optimism at a time in my life when I was absolutely not confident and certainly not optimistic. I know now, of course, it was neither of those things—really, it was desperation—but I know a lot of things these days that I didn’t know back then.

I’m not particularly attracted to men, and so what women probably have liked best about you was probably not what I liked about you. I was attracted to your smile, though. You smiled often, and the smile was easy and warm, but always a little sad. I liked that. I recognized that. I saw something of myself in it. That’s why I picked you. Privately, too, I always thought you had a rather feminine mouth.

I can’t imagine the impression I must have made on you then, a skinny, hungry-eyed creature with long red-blond hair in a wild braid, a shirt full of holes, and a hatchet on their belt. My left hand was still wrapped in a dirty bandage from a dog bite fracture, and a severed tendon. You told me later that it was this detail that made you like me best, that I was strange and wild and obviously hurt, walking around out there in the backcountry, where you definitely need two hands to have a shot at surviving, my one, bad hand sticking out from my shirt sleeve like a fuck you to god and my own thin mortality.

Do you remember—how could you not?—how brazen I was when I approached you? I’m interested—are you? Direct and to the point. Men and women aren’t like this, I know that now; you heterosexuals make things so needlessly complicated, are so attached to your gender roles. I was sitting next to you at the fire, flirting a little, half-cut on a quart of Kraken, and everyone else was chattering away about something else, and I just leaned over and met your eyes and asked if you’d like to sleep with me.

I was hurting, I said. I’d been betrayed. I wanted some comfort, but the thought of letting a woman touch me filled me with revulsion. The wound was too fresh. I was too angry. I wanted something new in the meantime. I hadn’t been with a man in nearly a decade—I was twenty-nine. If you wanted me, you could have me, provided I was in charge of how things went down.

I was curious. I was terribly lonely. I had a plan.

You sat there drinking Fireball—cheap-ass corn liquor like liquid cinnamon hearts—and listening intently. I had a hand on your thigh, was looking into your face. You were thirty-three, had the beginnings of lines around your mouth, around your eyes, which were dark brown, so dark they were nearly black. When I finished, you were a bit flustered, but you said thank you, of all things, like you were flattered by something thoughtful I had done for you. Thank you, you said, but no—you liked me and you didn’t want to complicate things and you would be moving on soon, and besides which I was very drunk and it wouldn’t be right.

I listened and shook my head. That all seemed very reasonable. I said I liked you, too. I seem to remember we shook hands, even. You had very broad, strong hands. I have very small, strong hands. We both had thick calluses on the pads of our fingers, across the tops of our palms.

Then we got absolutely shitbagged, and I got really sad about Gabrielle and tried to get in my truck to drive three hours into cell service so I could call her, and Patricia quite rightly slapped me in the face and took my keys.

The next day, when you saw me, we were both hung over. You smiled at me, chagrined, as if it had been you who’d made such a ridiculous drunken proposal, and I smiled back at you. It made me like you more, this good-natured shyness.

I thought that because you’d said no—because I’d been too drunk and you’d known that and didn’t want to take advantage of me—you were a good guy. I thought it meant you had a sense of honour. I thought it meant you were safe.

Like I said. There were a lot of things I didn’t know back then.

_____

Bush time is so funny, eh, Lucky? An hour in the backcountry could feel like a year, a day could be twenty minutes. It feels like months passed after that, but really it couldn’t have been more than a week or so. I was either half-cut all of the time or all-cut half of the time, depending on how you looked at it, so maybe that had something to do with it.

We were on good terms. I saw you around a bunch. You came over to hang out with us, have a drink sometimes with our picking crew: Patricia and her new fellow, a tall, bearded farm boy from the Shuswap; Patricia’s sister Annie who was up from Ontario on an adventure, intending in the end to get away from her current boyfriend, who was still back in the central eastern time zone; and Clay, Patricia’s boyfriend’s friend, a big-hearted, cantankerous fiftysomething-year-old man who had worked in the bush all his life and would be found ten months later dead of a drug overdose in his trailer, struck down by fentanyl-laced crack cocaine.

Clay—five foot three if he was a foot, built like Popeye, who swore up and down whenever he got good and drunk (which was often) that one time he had seen a lady sasquatch “with big hairy titties”—tried to warn me about you, actually. With the solemnity only a serious alcoholic can affect, he’d say that you were no good, that there was a reason no one in camp wanted to team up with you, that you did bad things for money and couldn’t be trusted. At first, I had half a mind to listen, but then it came out that Clay, who I called “Uncle,” was going around behind my back telling everyone how he was going to fuck me, and I was so disappointed in him that I disregarded his advice as possessive jealously.

Which it was, it’s just that it was also right.

The morels were petering out in the lowlands, so we all hauled up an old ATV trail to the high country. Burned as fuck, too burned and too dry for anything to grow. We called it “crunchy country” because of the sound the burned lichen made when you walked on it. I don’t think we found a single goddamn thing up there, not one fucking basket. I can’t remember if you came with us or if you went into the deep back, over to the other side of the mountain with Fred. Fred would, in short order, become Annie’s new lover, but I think this was before that.

I was still stoned by grief over what Gabrielle had done, and so I remember only two things clearly from that time. The first is the terrible, tremendous thirst; we had been told there was water, but by “water” the buyer meant “stagnant pool of green slime with a beaver swimming in it.” Someone had stolen my water purification pump, we had only one small cooking pot to boil water in, and fuel was limited—the fire hadn’t left much left behind when it had torn through. I resisted drinking that beaver water for days, but eventually caved—there was no other choice. I remember it tasted like wet socks. Years later, I joked with a friend that drinking that water was what kept me healthy during the pandemic—if we had swallowed that and not died of giardia or tapeworms or dysentery, we must be immune to pretty much everything.

The second thing is your friend: tall, skinny as a hare and about half as bright, but I’ll be fucked if I can recall his name now. I remember that he had come with you and Fred, that he had that old white beater car, the “bog buggy,” all full of Chicken McNuggets boxes and empty beer cans stuffed full of cigarette butts. You could hear the muffler a mile off before you saw the car, and you could smell it—burning oil, stale smoke, the musky animal odour of unwashed male bodies—a mile after it was gone. I wasn’t very attracted to him. I found him annoying and desperate, and I hated the way he tried to mansplain basic chores to me, like cutting wood or fishing for pike, all of which I was better at than him, that little city shit. It was the cheese incident that really turned me off him, though. He had hiked in with a litre of heavy cream and, finding no cold running water to keep it from spoiling, decided to leave it out in the hot sun to make “cheese.” I came back late from a pick with Annie and there he was, sick as a dog, lying on his belly in the shade and moaning, the smell of sweat and puke and spoiled milk coming up off him in a stink that was almost tangible, like the cartoon wafts that follow Pepé Le Pew. The idiot had mixed the curdled mess of the “cheese” into his noodles and eaten it all. I know my entire sexual orientation isn’t much geared for the survival of the species, but if you think milk left out at 30 degrees becomes cheese and then eat it despite the odour screaming don’t fucking eat this at your entire olfactory system, your genes need to stay far, far away from mine, thank you very much.

I’d flirted with him for like, twenty minutes, then decided I didn’t want anything to do with ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- At Your Service

- Creatures of Impossible and Tremendous Beauty

- The Happy Family Game

- Every Little Act of Cruelty

- Where the Fuck Are We in Your Dystopia?

- Other People’s Houses

- The Hour You Are Most Alone

- After the Hungry Days

- Call You by Your Name

- This Has Always Been a War

- The Lame One

- Acknowledgments

- Endnotes