- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy floods devastated coastal areas in New York and New Jersey. In 2017, Harvey flooded Houston. Today in Miami, even on sunny days, king tides bring fish swimming through the streets in low-lying areas. These types of events are typically called natural disasters. But overwhelming scientific consensus says they are actually the result of human-induced climate change and irresponsible construction inside floodplains.

As cities build more flood-management infrastructure to adapt to the effects of a changing climate, they must go beyond short-term flood protection and consider the long-term effects on the community, its environment, economy, and relationship with the water.

Adapting Cities to Sea Level Rise, by infrastructure expert Stefan Al, introduces design responses to sea-level rise, drawing from examples around the globe. Going against standard engineering solutions, Al argues for approaches that are integrated with the public realm, nature-based, and sensitive to local conditions and the community. He features design responses to building resilience that creates new civic assets for cities. For the first time, the possible infrastructure solutions are brought together in a clear and easy-to-read format.

The first part of the book looks at the challenges for cities that have historically faced sea-level rise and flooding issues, and their response in resiliency through urban design. He presents diverse case studies from New Orleans to Ho Chi Minh to Rotterdam, and draws best practices and urban design typologies for the second part of the book.

Part two is a graphic catalogue of best-practices or resilience strategies. These strategies are organized into four categories: hard protect, soft protect, store, and retreat. The benefits and challenges of each strategy are outlined and highlighted by a case study showing where that strategy has been applied.

Any professional or policymaker in coastal areas seeking to protect their communities from the effects of climate change should start with this book. With the right solutions, Al shows, sea-level rise can become an opportunity to improve our urban areas and landscapes, rather than a threat to our communities.

As cities build more flood-management infrastructure to adapt to the effects of a changing climate, they must go beyond short-term flood protection and consider the long-term effects on the community, its environment, economy, and relationship with the water.

Adapting Cities to Sea Level Rise, by infrastructure expert Stefan Al, introduces design responses to sea-level rise, drawing from examples around the globe. Going against standard engineering solutions, Al argues for approaches that are integrated with the public realm, nature-based, and sensitive to local conditions and the community. He features design responses to building resilience that creates new civic assets for cities. For the first time, the possible infrastructure solutions are brought together in a clear and easy-to-read format.

The first part of the book looks at the challenges for cities that have historically faced sea-level rise and flooding issues, and their response in resiliency through urban design. He presents diverse case studies from New Orleans to Ho Chi Minh to Rotterdam, and draws best practices and urban design typologies for the second part of the book.

Part two is a graphic catalogue of best-practices or resilience strategies. These strategies are organized into four categories: hard protect, soft protect, store, and retreat. The benefits and challenges of each strategy are outlined and highlighted by a case study showing where that strategy has been applied.

Any professional or policymaker in coastal areas seeking to protect their communities from the effects of climate change should start with this book. With the right solutions, Al shows, sea-level rise can become an opportunity to improve our urban areas and landscapes, rather than a threat to our communities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adapting Cities to Sea Level Rise by Stefan Al in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Architektur Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Aftermath on the Jersey Shore

Flood-damaged homes dot the shore after Superstorm Sandy. Some homes even completely disappeared.

(Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-Northeast Region, Wikimedia Commons)

Climate change is a severe and growing challenge for twenty-first century cities, from droughts to forest fires and from storms to rising sea levels. The most tangible changes are related to water. Some areas will have too little water; others too much. Coastal cities will be strongly affected by the latter, as rising seas increase the occurrence of disruptive or nuisance flooding in urbanized areas during high tides, not just during storms. Water threats in coastal cities can even come from all directions: increased rainfall from above, rising groundwater from below, floods from rivers, and floods from the sea—all worsened by climate change and land subsidence.

Currently, sea levels are rising on average 3.2 millimeters (0.13 in) per year,1 but this number is expected to rapidly increase as average temperatures rise, with roughly seven and a half feet of sea level rise expected per degree Celsius of warming. Even the conservative 2 degrees Celsius of temperature increase, the goal of the Paris Agreement, would likely cause sea levels to rise an average 4.6 meters (15 ft), putting coastal cities at risk and some countries, such as the Maldives, entirely under water. Climate Central estimates that two degrees Celsius of warming would lock in 6.1 meters (20 ft) of sea level rise in Miami, leaving almost the entire city underwater. But a mere 0.91-meter (3 ft) rise in Bangladesh would submerge 20 percent of that country, displacing as many as 30 million people. Rising sea levels alone will usher in an entirely new category of human tragedy: the “climate refugee.” Rising water also leads to more powerful storm surges and greater flooding on already vulnerable coastlines, forcing more residents to retreat and relocate.

New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina

(Source: CAN Europe, Flickr)

Sea level rise, even a small increase, can dramatically disrupt the day-to-day operation of cities, potentially threatening people’s access to power and safe water. Climate change causes extreme weather events, such as floods, to be more recurring and intense, jeopardizing not only the aboveground transmission and distribution electricity networks, but even areas with buried power lines. Furthermore, power outages can cause wastewater treatment plants to malfunction, leading to potentially unsafe water. But flooding can also threaten the functioning of the water system in other ways. Water and sewage plants are typically located at geographic low points, such as along coastlines, to aid wastewater flowing to plants by gravity, which makes them susceptible to overflows at high tides. In addition, stormwater could flow back into the system’s discharge pipes, causing backflow. The higher the water level is, the larger the amount of river water flowing back into the drainage system outfalls. When saltwater breaches a plant’s treatment system, it could leave permanent damage. Finally, floods can cause saltwater intrusion in coastal freshwater aquifers, as happened during Hurricane Katrina.2

Compounding the problem is the rapid urbanization of coastal areas. Human settlement will continue to favor coastal areas, for their benefits of ports, recreation, fishing, and potentially moderate temperatures. In China, for instance, the fastest growing and largest cities, such as Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Tianjin, all face rising rivers and oceans. These three cities alone have added about 40 million people combined in the last thirty years. With the world urban population expected to grow by another two and a half billion by 2050, the problems will only increase.3 The World Bank predicts that by 2050, $1 trillion or more of assets will be at risk every year in cities worldwide.4

Sea level rise will also threaten natural habitats in coastal areas. As seawater reaches farther inland, it can cause land erosion, flooding of wetlands, saltwater intrusion in aquifers, and contamination of agricultural land, potentially causing the loss of habitat for plants and various species of birds and fish.

The best way to prevent these losses would be to avoid climate change altogether, or to mitigate the effects by reducing emission levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, or to stabilize them, such as through the efforts of the Paris Agreement. But since we are already realizing the effects of climate change, cities will also need to adapt to challenges such as sea level rise. One way to respond to future or present flooding problems is by building flood management infrastructure.

A typical approach to floods deals only with the symptoms of the problem. This approach includes increasing a community’s “resilience”—in the shallow definition of the term—by improving the capacity to bounce back from a disaster. Examples include evacuating areas before a disaster, temporarily housing people in emergency shelters, or paying out insurance claims after the damage is done, in order to rebuild afterward. But this is very costly, with billions of dollars of losses from floods. Experts advocate for disaster prevention rather than treatment. The Federal Emergency Management Agency estimates that every dollar spent on the reduction of a community’s vulnerability to disasters saves people approximately six dollars in economic losses.5

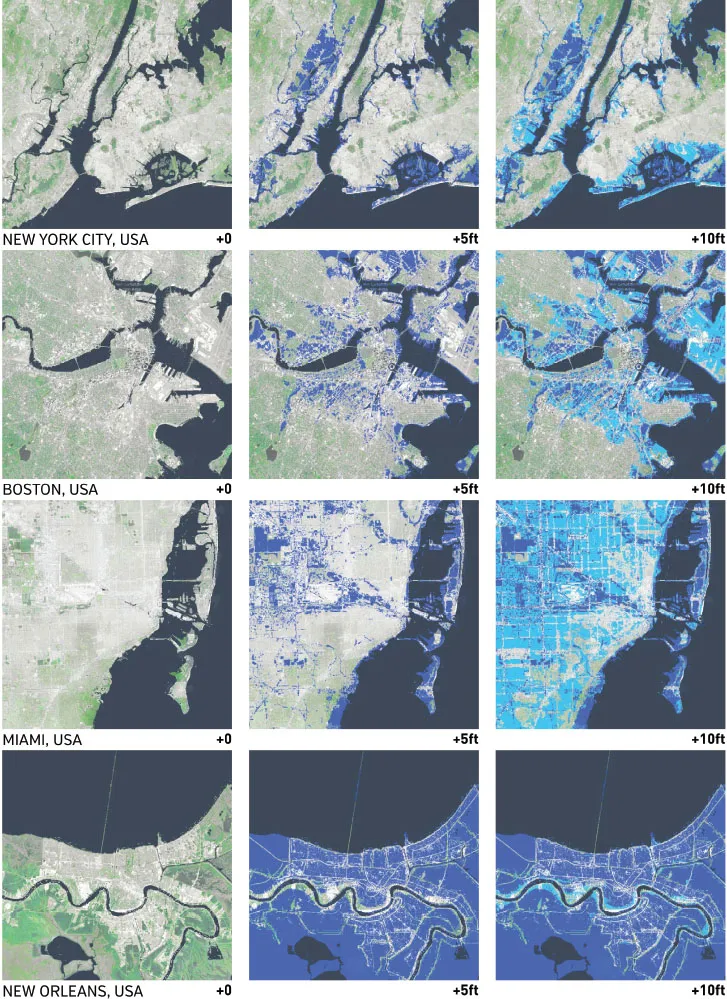

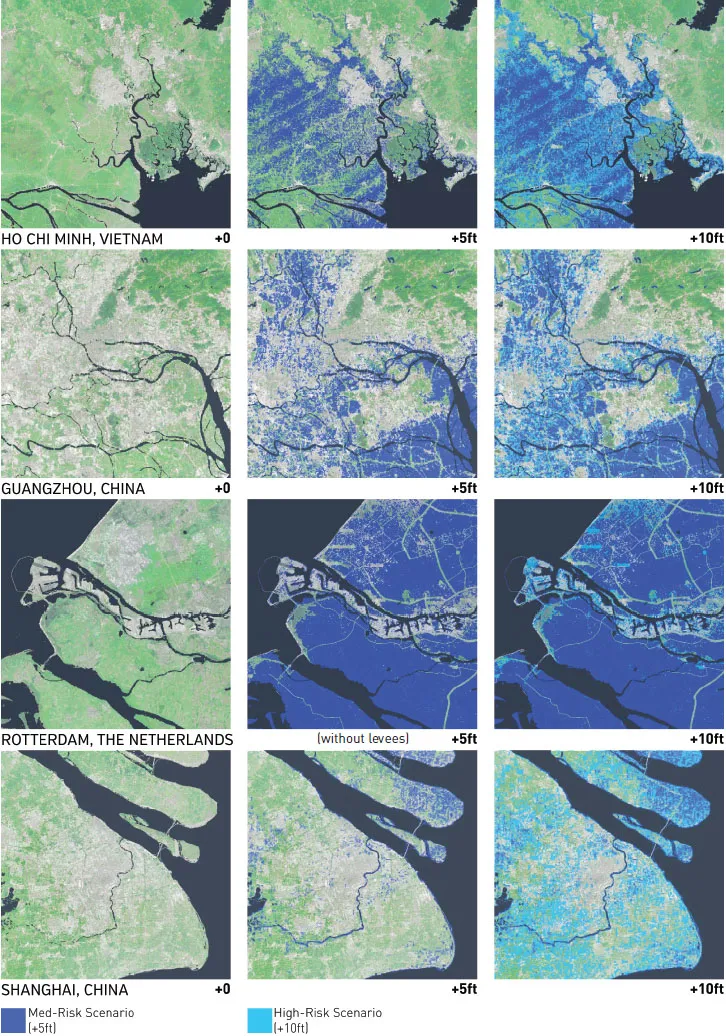

WORLD CITIES SEA LEVEL RISE THREAT UNDER MEDIUM-AND HIGH-RISK SCENARIOS

(Adapted from: Climate Central, Surging Sea-Risk Zone Map, http://sealevel.climatecentral.org/)

WORLD CITIES SEA LEVEL RISE THREAT

(Adapted from: Stephane Hallegatte et al., 2013, Natural Climate Change, http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/climate-change-economics/coastal-cities-map)

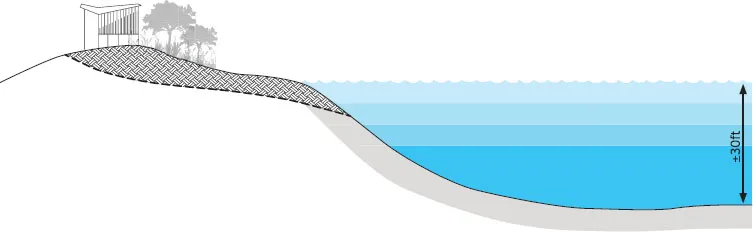

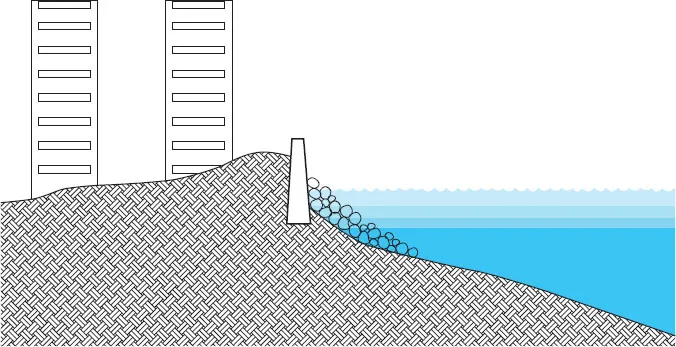

Another approach to floods—building dikes and seawalls—provides only a short-term stopgap. Imagine a beach house with a beautiful view of the shore. Suddenly, the view is of a concrete wall. A seawall can be a real beach killer in many ways. When a wave strikes a seawall, wave energy is reflected back and carries sand offshore. If the sand is not replenished, the shore will erode and the wall will eventually be undermined, and the environmental harm is done.

Flood management solutions need to be considered beyond their short-term effect to their long-term impact on communities, environments, and economies. They need to respect a community’s relationship with the water, as well as the ecological and environmental health of the surrounding area. They should also lead to economic benefits beyond just protecting from floods—for instance, by unlocking the real estate and economic development potential of the newly secured areas, which could help pay for the infrastructure. In short, flood management infrastructure should not only protect from floods, but should be integrated into the landscape and the public realm. New infrastructure built in or near our cities should be balanced with place-making.

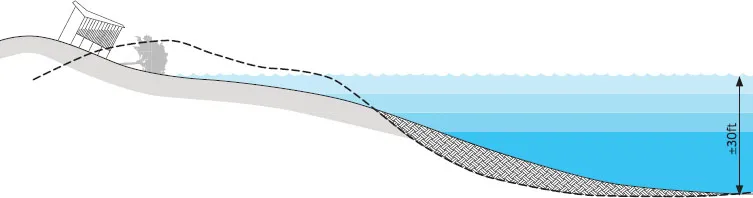

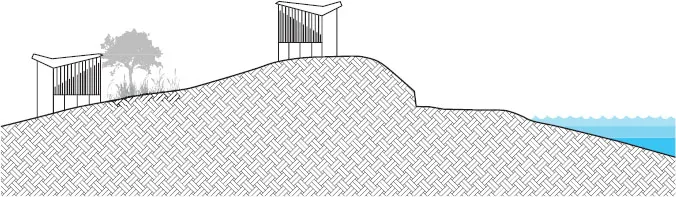

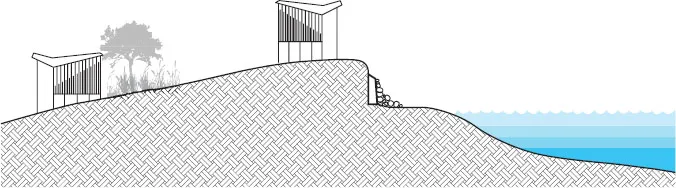

BEACH REPLENISHMENT FAILURE AND BEACH DYNAMICS

Before the storm

To enjoy sea views, beachfront development has been built on many parts of vulnerable shorelines.

After the storm

During the storm, wave action moves sand from the upper beach to the lower beach, weakening structural integrity underneath beach houses.

Before replenishment

Before sand replenishment, there is no exposed sandy beach. There is only a narrow beach at low tide.

Immediately after replenishment

Sand berm was constructed to prevent storm surge and to enhance recreational use.

1-3 years after replenishment

Most of the sand berm has been washed away, except at the top of the berm. However, neither purpose of the new beach—storm protection or recreation—is achieved.

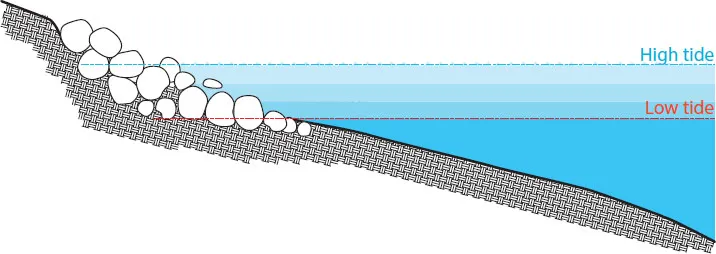

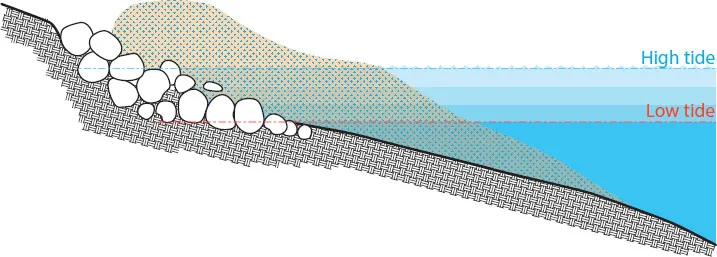

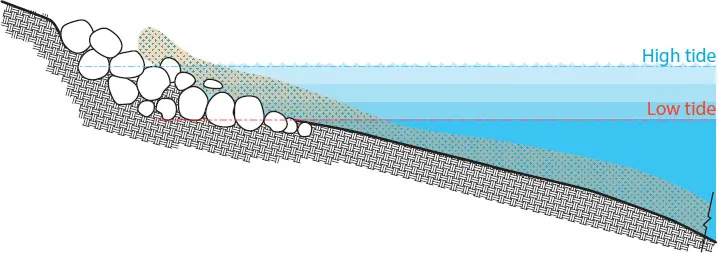

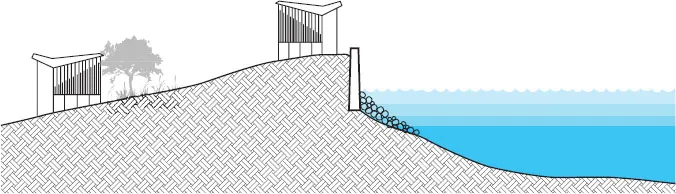

FLOODWALL + BEACH

Before the wall

Sand dunes are often eroded away as a result of natural processes.

Wall constructed

Homeowners react to the erosion by building a small-scale wall.

2-40 years later

People build higher walls to deal with erosion. In the process the beach disappears.

10-60 years later

Higher-density developments replace cottages and beach houses. A bigger seawall is required for storms.

This book, Adapting Cities to Sea Level Rise, aims to introduce design responses to sea level rise, drawing from examples around the globe. Going against standard engineering solutions, it argues for approaches that are integrated with the public realm, nature-based, and sensitive to local conditions and the community. In short, it features design responses to building urban resilience that create new civic assets for cities. Resilience here is used in the more complex meaning of the term, defined by the Rockefeller Institution’s 100 Resilient Cities program as the “capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, business, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.”6 In contrast to the technical definition, this broader definition of resilience has the potential to transform a city.

Fortunately, there are ways in which smart design of flood management infrastructure can make a real difference. For instance, a standard solution of building a revetment—a sloped surface typically built of concrete rocks that dissipate wave energy—has all the charm of a military bunker and can block human access to the shore. In contract to this typical engineering solution, a “designed” solution incorporates other parameters beyond flood protection, such as human use. For instance, the beach town of Cleveleys, United Kingdom, integrated public spaces into flood protection. Instead of a standard revetment, the city built a sinus-shaped structure with amphitheater-like viewing spaces and steps. The steps accentuate the beautiful curvilinear shapes while creating access to the beach and even adding to public space, which is important for a coastal town that relies on tourists.

Nature can play an important role in flood management infrastructure. Instead of reinforced concrete defenses that get the full force of waves and will finally succumb to the undercurrent of the sea, there are solutions that rely on nature’s long-term capacity to adapt. Dunes, for instance, are more sustainable sea barriers to absorb the force and velocity of waves, and can also add to the landscape and provide na...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword by Edgar Westerhof

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Part I: City Strategies

- Part II: Local Strategies

- Notes

- Index