eBook - ePub

Kids Have All the Write Stuff

Revised and Updated for a Digital Age

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kids Have All the Write Stuff

Revised and Updated for a Digital Age

About this book

You can open up a world of imagination and learning for children when you encourage the expression of ideas through writing. Kids Have All the Write Stuff: Revised and Updated for a Digital Age shows you how to support children's development as confident writers and communicators, offering hundreds of creative ways to integrate writing into the lives of toddlers, preschoolers, and elementary school students—whether at home or at school.

You'll discover:

· how to implement writing as a part of daily life with family and friends;

· processes and invitations fit for young writers;

· strategies for connecting writing to math and coding;

· writing materials and technologies; and

· creative and practical writing ideas, from fiction, nonfiction, and videos to blogs and emails.

In order to connect writing to today's digital revolution, veteran educators Sharon A. Edwards, Robert W. Maloy, and Torrey Trust reveal how digital tools can inspire children to write, and a helpful companion website brings together a range of resources and technologies. This essential book offers enjoyment and inspiration to young writers!

You'll discover:

· how to implement writing as a part of daily life with family and friends;

· processes and invitations fit for young writers;

· strategies for connecting writing to math and coding;

· writing materials and technologies; and

· creative and practical writing ideas, from fiction, nonfiction, and videos to blogs and emails.

In order to connect writing to today's digital revolution, veteran educators Sharon A. Edwards, Robert W. Maloy, and Torrey Trust reveal how digital tools can inspire children to write, and a helpful companion website brings together a range of resources and technologies. This essential book offers enjoyment and inspiration to young writers!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kids Have All the Write Stuff by Robert W. Maloy,Sharon A. Edwards,Torrey Trust in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Inspiring Young Writers

Children write wherever they are: in homes and schools; in restaurants or laundries or doctors’ offices; in cars, buses, ferries, planes, and subways. They write with pencils, pens, crayons, markers, keyboards, and touchpads. They write with their voices when they dictate words into computers and audio recorders or tell stories to adults. They write on paper, computers, tablets, smartphones, whiteboards, cloth, and any other surface they can find. They write by themselves and with parents, teachers, family members, classmates, siblings, and friends.

Children’s writing is spontaneous, playful, creative, self-absorbing, and expressive. On their own, children choose writing topics and genres; freely explore words and their meanings; have fun with shapes, letters, numbers, and symbols; and combine writing with art and drawing to communicate ideas and images in their minds. As they cut, paste, staple, and print pages of their writing, they may talk, laugh, and interact with friends and adults or concentrate quietly for long periods of time.

This book showcases the writing of children who became confident in their ability and resolute in their desire to write with the encouragement of friends and adults—parents, teachers, family members, tutors, and caregivers. These children learned to try and to enjoy all kinds of writing—alphabets, letters, lists, signs, recipes, poetry, fiction stories, chapter books, making maps, math comics, I Wonder Journals, news reports, weather reports, and nonfiction pieces. These written creations arose from their natural curiosity, creativity, and desire to tell stories, express ideas, and understand themselves and their lives. All these youngsters sharing their experiences have taught us why writing is a powerful force for children’s learning. Here are the stories of a few of them.

Stories of Children Writing

“Christina Writing”

Since she was a baby, Christina had heard the alphabet song almost every day. As soon as she could say the letter names, her mother would stop singing to let Christina put the letters into the song: “A, B, C, __E, F, __, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, __, Q, R, S, __, U, V, W, X, Y, __.” Every day, Christina sees letters and words in books and throughout her home. A small alphabet quilt with pockets hangs on her bedroom doorknob within easy reach. Each pocket has a letter on it and contains an object beginning with that letter sound. She takes these objects out of their pockets and puts them back in other places on the quilt. Then she plays a “Where Is Your Home?” game with her mother: “No, no doggie, not your home!” she sings as she takes the little dog out of the M pocket. “No, no yo-yo, not your home!” she continues, and the yo-yo is returned back to the letter Y’s pocket. Christina regularly hears stories, sees her parents reading and writing, and receives encouragement for her own first scribbles. Her mother points out letters to her and writes her name so she can see it in print. Even at this young age, Christina recognizes letters as writing. She is doing what young children do, associating words with objects and letters with words while playing games, singing songs, and hearing stories. As Christina makes lines on paper, she points at her marks and says, “A, C.” Her mother refers to the scribbles and marks as writing. One day, busily making lines and squiggles on paper, she looked up and proclaimed, “Christina writing!”

“I Could Be A Writer”

Since she was three years old, Kylie has regularly engaged in reading and writing activities with members of her family—hearing books read aloud by adults and computers, composing lists and letters, drawing pictures, and telling oral stories. Entering kindergarten at age five, Kylie enjoyed the classroom setting filled with so many choices for playing, building, creating, and problem-solving. A favorite area was the writing table where she composed stories in her own spelling. Nearby was the reading area with favorite books and the block area where she and classmates constructed elaborate wooden structures filled with imaginary creatures whose stories they expressed in vivid language. Always full of questions, Kylie wondered about science and nature and what scientists do, as she was constantly taking apart and reassembling battery-powered toys and investigating personal questions about how these devices work. In the car riding home from school one day, Kylie asked, “How do people write books?” Her mother explained that people write about topics they think are important or interesting and then their words are published in books or online for people to read. That night, after her mother reminded her that she could be anything she wanted to be when she grew up—an engineer, a mathematician, a computer programmer—Kylie replied, “I could be a writer.”

“The Boy Who Writes the Most Books in the World”

Clayton had been making greeting cards for friends and relatives at his mother’s suggestion and with her help since he was three. Clayton drew the illustrations, and while his mother spelled the words aloud, he wrote, “Happy Birthday” or “Happy Fourth of July.” A quiet youngster usually, on the day he and his first-grade classmates each received a Writing Box at school filled with new writing supplies, he jumped in the air with joy, shouting, “I can’t wait to use this!” Two weeks later, he brought to school his first two stories written at home and announced excitedly, “I wrote fiction and nonfiction. This is the first time I ever wrote nonfiction.” A month later, a doctor meeting him for the first time asked what he liked to do. Clayton replied confidently, “I write!” At home, Clayton wrote between two and three stories a day, over 150 pages of writing in four months since receiving his Writing Box. He did not ask for assistance with choosing topics or spelling words, and he did not discuss his stories while writing them; when completed, he read them to his parents. At school, watching an adult type his stories on a computer, Clayton remarked, “I better slow down. You can’t keep up with me.” Later that week, he proclaimed, “I want to be the boy who writes the most books in the world!”

“I Just Figure It Out”

“It wasn’t too difficult,” said ten-year-old Kennisha, recalling how she began using a computer for writing at home two years before. “The machine tells you what to do,” she said. “If you need help, press help or Google it or whatever. I just figure it out.” For Kennisha, writing with a keyboard and a screen was “quicker . . . neater . . . just easier.” Computers were not new to her; she had played games on one at school and at her friend’s house. When her mother told her she could begin using the family computer at home, she started exploring the hardware and the software, figuring things out for herself with “a little help from my mom.” Soon she was writing fiction stories and factual reports for school, saving them to the cloud so she could look at them later. Typing was not a problem—“I just practiced,” she replied when asked about using a keyboard. Most important to her was how enjoyable it was to write with a computer. Once, Kennisha said laughingly, she and her friend decided to write “75, maybe 100 sentences just for the fun of it.”

Adults who are unacquainted with children and writing wonder if these stories are exaggerations or exceptions. The joy, excitement, creativity, and self-expression shown by Christina, Kylie, Clayton, Kennisha, and all the other youngsters whose writing is showcased in the upcoming pages is real. Their writing demonstrates what youngsters can and will do when they receive interest, support, and encouragement from adults.

Bookcase for Young Writers

Chapter 1: Inspiring Young Writers

- http://umass.edu/umpress/KHAWSBookcase1

- Read the text of a child’s Bill of Writes.

- Learn about the history of writing, including the five original writing systems around the world.

- Discover the history of paper and paper-making.

- Find out when the internet was created and first text messages were sent.

- Read that the United Nations has declared access to the internet is an essential human right.

Children Are Writers Right Now

Children are writers right now. On what evidence do we base this belief? From young ages, children have ideas and images in their minds and a desire to communicate those to others. More than a century ago, physician and educator Dr. Maria Montessori found in her school for impoverished Italian youngsters that children begin writing sooner and in more ways than adults imagined possible.

What writing can young children do while learning to form letters, spell words, add punctuation, and compose sentences? ALL KINDS! Children write from their experience and from their imagination. They produce remarkable communications and creations and delight in playing with letters, words, and symbols and discovering what happens when they make those marks on paper or on screens. The list below shows just some of the different kinds of writing we have seen children do.

What Children Write

- • Signs

- • Grocery lists

- • Fiction stories

- • Nonfiction stories

- • Letters and emails

- • Menus

- • Recipes

- • Maps

- • Birthday cards

- • Charts and graphs

- • Song lyrics

- • Concrete or picture poems

- • Acrostic poems

- • Diaries, journals, and blogs

- • Chapter books

- • Plays

- • Captions for drawings and photos

- • Thank-you notes

- • Jokes

- • Newspaper stories

- • Rhymes

- • Alphabets

- • All about books and All about Me books

- • Text messages and social media posts

- • Mazes and puzzles

- • Movie reviews

- • Riddles

- • Notes and messages

- • Surveys

- • Comics

- • Made-up words

- • Homework assignments

- • Rules for games

- • Postcards

- • Book reviews

- • Haiku poems

How Children’s Writing Evolves

Children’s writing evolves in predictable patterns from preschool through the elementary grades.

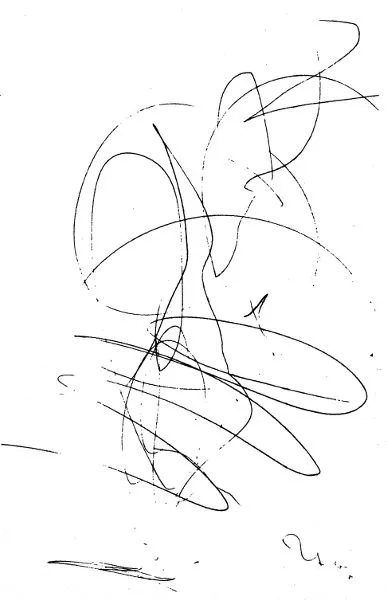

Squiggles, Circles, Lines, and Scoops. Picking up a pencil or crayon, toddlers and preschoolers make squiggles, lines, and scoops on paper or other surfaces without needing a model to do so. These first steps of writing can be noted and celebrated by adults (fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Christina’s writing at twenty months old.

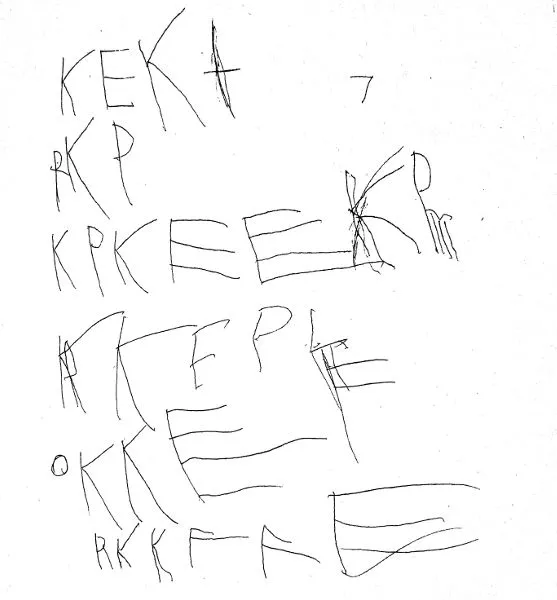

Strings of Letters. As preschoolers’ hand, finger, and arm muscles coordinate movements, youngsters approximate writing letters and create strings of letters to make text. One letter may represent one word or several. Children may repeatedly use letters they know how to make, often the ones in their name, as in the following greeting card from Kyle to Bob (fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Four-year-old Kyle’s birthday greeting to Bob.

[Big Bob’s Birthday Blow-Up. Open the door and you will have a party].

Children’s marks and letters reflect their knowledge of print and serve many purposes simultaneously—exploring how to make symbols, transmitting information, and approximating writing. Whole words or entire sentences may be conveyed by a single mark, symbol, or letter. One youngster read his story aloud to his first-grade teacher. He had written a string of ten letters. Asking his permission to do so, the teacher wrote the words he said in small print at the bottom of the page so she would not forget the story. Looking at what she did, he took back the paper, saying of his writing, “Not enough letters,” and went away to add more. Seeing his words written by an adult, he realized what he learned next—more words need more letters.

Approximations of Letters. Making approximations of words with their early scribbles, preschoolers produce their writing (fig. 1.3). These marks may not look like letters, they may be backwards, sideways, or upside down. They do not represent sounds in words, but they do convey text.

Figure 1.3. Four-year-old Sam’s letter to Big Bear (with a bear drawn by his mother).

Combinations of Invented and Standard Spellings. A child’s name and often seen words (“Mom,” “Dad,” “dog”) may be the first conventional spellings, what we call “book” spelling, to appear in a young child’s writing. As youngsters recogn...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- A Bill of Writes

- Preface to the Revised and Updated Edition

- A Note to Readers

- Chapter 1. Inspiring Young Writers

- Chapter 2. Writing Boxes and Writing Technologies

- Chapter 3. Writing Processes Fit for Young Writers

- Chapter 4. Writers Are Readers, Too

- Chapter 5. Writing with Family and Friends

- Chapter 6. Photo-Taking, Video-Making, and Blogging

- Chapter 7. Playing with Language in Rhymes, Songs, and Poems

- Chapter 8. Writing Fiction and Nonfiction Stories

- Chapter 9. Math, Coding, and Making

- Chapter 10. Alphabets, Spelling, Keyboarding, and More

- Notes

- Index