- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The American College Town

About this book

The college town is a unique type of urban place, shaped by the sometimes conflicting forces of youth, intellect, and idealism. The hundreds of college towns in the United States are, in essence, an academic archipelago. Similar to one another, they differ in fundamental ways from other cities and the regions in which they are located.

In this highly readable book—the first work published on the subject—Blake Gumprecht identifies the distinguishing features of college towns, explains why they have developed as they have in the United States, and examines in depth various characteristics that make them unusual. In eight thematic chapters, he explores some of the most interesting aspects of college towns—their distinctive residential and commercial districts, their unconventional political cultures, their status as bohemian islands, their emergence as high-tech centers, and more. Each of these chapters focuses on a single college town as an example, while providing additional evidence from other towns.

Lively, richly detailed, and profusely illustrated with original maps and photographs, as well as historical images, this is an important book that firmly establishes the college town as an integral component of the American experience.

In this highly readable book—the first work published on the subject—Blake Gumprecht identifies the distinguishing features of college towns, explains why they have developed as they have in the United States, and examines in depth various characteristics that make them unusual. In eight thematic chapters, he explores some of the most interesting aspects of college towns—their distinctive residential and commercial districts, their unconventional political cultures, their status as bohemian islands, their emergence as high-tech centers, and more. Each of these chapters focuses on a single college town as an example, while providing additional evidence from other towns.

Lively, richly detailed, and profusely illustrated with original maps and photographs, as well as historical images, this is an important book that firmly establishes the college town as an integral component of the American experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The American College Town by Blake Gumprecht in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

DEFINING THE COLLEGE TOWN

The American college town is a unique type of urban place, shaped by the sometimes conflicting forces of youth, intellect, and idealism, that has been an important but overlooked element of American life. The hundreds of college towns in the United States are, in essence, an academic archipelago.1 Similar to one another, they differ in fundamental ways from other cities and the regions in which they are located. They are alike in their youthful and comparatively diverse populations, their highly educated work forces, their relative absence of heavy industry, and the presence in them of cultural amenities more characteristic of big cities. They are typically more liberal than towns without prominent colleges. They tend to be more tolerant of unusual behavior and supportive of unconventional ideas. Some have become centers for high technology development. The attributes of the institutions located in college towns and the people who live in these places, furthermore, breed unusual landscapes—the campus, fraternity row, the college-oriented shopping district, and more.

What is a college town? I consider as a college town any city where a college or university and the cultures it creates exert a dominant influence over the character of the town. This definition is deliberately imprecise because I do not believe there is a clear distinction between a college town and a city that is merely home to a college. They vary along a continuum. I will focus on towns where colleges are clearly dominant. I will not devote significant attention, for example, to cities such as Austin, Texas, that are home to big universities but are also state capitals. State governments, their employees, and related activities exert a strong influence. Similarly, I will say little about big cities that are home to universities or separately incorporated college communities like Tempe, Arizona, that are part of larger urban areas, because the socioeconomic diversity of such places dilutes the influence of a college. Although Austin and Tempe possess some of the attributes of college towns, particularly in areas closest to campus, what makes the college town as I envision it different is that the impact of a collegiate culture is concentrated and conspicuous. Small cities like Ithaca, New York, and Manhattan, Kansas, are defined by colleges and all that go with them.

The degree to which a college shapes the life of any place can be evaluated in a variety of ways, but none is sufficient to enable us to determine unequivocally which cities are college towns and which are not. There are places most people would agree are college towns. Charlottesville, Virginia (fig. 1.1), springs immediately to mind. There are many other places that clearly are not college towns. New York City, for example, is not one, despite occasional attempts to market it as such. But what about the large number of places that fall somewhere between those extremes? Is it possible to measure college town-ness? I would argue no, but there are methods to gauge from a distance the extent to which a college influences a place and so can give us a sense. In my view, the best barometer of a college’s influence is the ratio of college students to overall population. I would argue that if the number of four-year college students equals at least 20 percent of a town’s population, then a collegiate culture is likely to exert a strong influence. The 20 percent threshold is somewhat arbitrary, but it is based on my knowledge of numerous places I consider college towns and the ratio of students to population in those places.2

But we need more to go on than that, because there are many places that meet the 20 percent requirement that I would not consider college towns. They may be part of larger urban areas. They may be so tiny that they aren’t really towns by any common definition of the word. We could consider other statistical measures to fine-tune our assessment. We could use data on the share of the labor force that works in education or the population that lives in group quarters such as dormitories, as Brian Berry did when he attempted to classify college towns. We could look at the portion of land area within a city occupied by colleges or universities, as Edmund Gilbert did in his study of university towns in Europe.3 We could consider the median age or the percentage of adult residents possessing a doctoral degree. Indeed, we could create a complex matrix of characteristics a city must possess to be considered a college town, but that would suggest this process is more scientific than it should be.

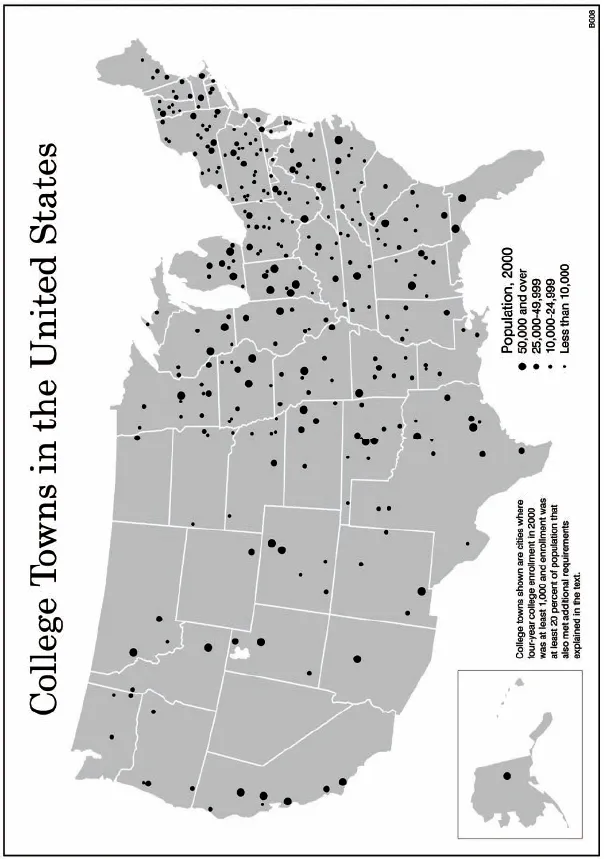

I chose to keep it simple and include on a provisional list of college towns all places that meet the 20 percent enrollment-to-population threshold, but also had an urbanized area population in 2000 of less than 350,000 (a college town can’t be too large), were nucleated urban areas that were physically separated from any larger city (to exclude suburbs and cities that are part of bigger urban agglomerations), possess a distinct identity apart from other places, and are perceived as college towns. Most of those requirements are somewhat subjective. I based my decisions on my own knowledge and research. When in doubt, I examined U.S. Geological Survey maps, collected Census data, conducted periodical and Internet searches, and consulted reference sources. In 2000, there were 305 U.S. cities that met all those requirements (fig. 1.2). There are probably more cities that should be considered college towns, but do not meet the 20 percent threshold (e.g., Grinnell, Iowa) or are located in large metropolitan areas (such as Berkeley, California). Not all my sixty study towns met the requirements, though my parameters were conservative and intended to exclude places about which there may be disagreement rather than include any place that might be considered a college town.

FIGURE 1.1. The Corner, a college-oriented shopping district across from the University of Virginia campus in Charlottesville. Photograph by the author, 2002.

Ultimately, whether a city is a college town is in the eye of the beholder. You may consider a city to be a college town that I do not and visa versa. That’s okay. My purpose is not to create a definitive system for classifying college towns. I am more interested in understanding and explaining what makes college towns distinctive.

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

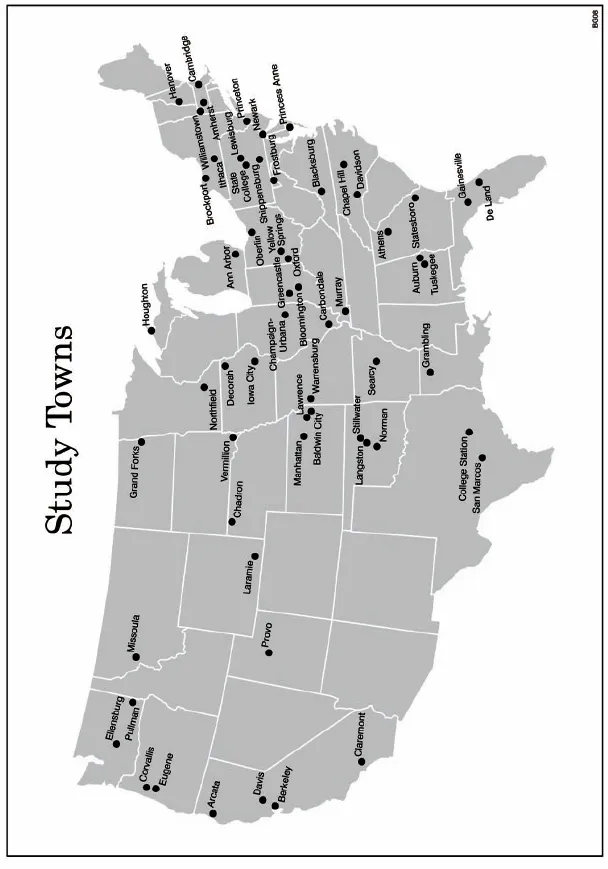

Much of what makes college towns unusual and interesting cannot be quantified in any meaningful way, and most of this book will take a humanistic and historical approach, but data on the socioeconomic characteristics of college towns confirm that they are fundamentally different from other places and from the United States as a whole. To begin, therefore, I will identify several distinguishing features of college towns that are measurable and significant, using data from the sixty study towns (fig. 1.3) as proof. Though some of these attributes are also present in other places, college towns are exceptional because most possess a majority of these traits, not just one or two, and because several are most strongly felt in towns where colleges are large relative to the size of the community.

College towns are youthful places. The migration to college towns every fall of new students and the exodus each spring of graduates makes college towns perpetually young (fig. 1.4). The average median age in the study towns in 2000 was 25.9 years old, ten years younger than the median for the United States.4 More than one-third of study town residents on average were aged 18 to 24. Some of the study towns were even more youthful than the group. In Oxford, Ohio, home of Miami University, two-thirds of all residents were 18 to 24. Because college town residents are young, they are also less likely than the general population to be married. Just 38.0 percent of study town residents 15 and over, on average, were married in 2000, compared to 54.4 percent for the nation.

College towns are highly educated. Because most academic appointments require a Ph.D. and many universities have large graduate student enrollments, college towns are among the most educated places anywhere. Adult residents in the study towns were on average twice as likely as the U.S. population in 2000 to possess a college degree and six times more likely to hold a doctorate. Almost half of study town residents 25 years and older on average were college graduates. Nearly 7 percent possessed a Ph.D. The educational differences between college towns and other places are most dramatic in small towns with elite colleges. In Hanover, New Hampshire, home of Dartmouth College, three in four adults were college graduates, 42.6 percent held a graduate degree, and 14 percent possessed a doctorate.

FIGURE 1.2. There were 305 cities in the United States in 2000 where enrollment in four-year colleges was at least 20 percent of the population and met other criteria suggesting they are college towns. Map by the author. For a complete list, go to http://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress/.

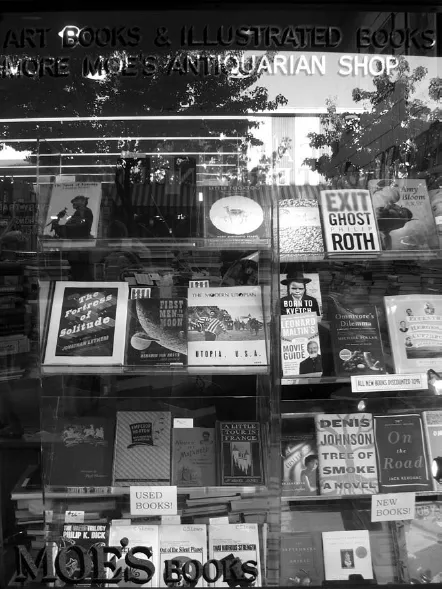

The educational level of college towns is reflected in other ways. Data on public library circulation and the presence of bookstores suggest college town residents read more for pleasure than the general population. Per capita public library circulation in 2002–03 in study towns for which data were available was 50 percent higher than in the United States. Bookstores were also more abundant per capita in the study towns than they were nationwide. The study towns averaged ten bookstores for every 100,000 residents in 2002. Nationwide, there were 3.8 bookstores per 100,000 residents. Berkeley had twenty-two bookstores (fig. 1.5). Gainesville, Florida, seat of the University of Florida, had fifteen.5

FIGURE 1.3. The sixty study towns that were the focus of research. Map by the author.

FIGURE 1.4. College towns are youthful places, as this scene of students jello wrestling at a fraternity party in Ithaca, New York, suggests. Photograph by the author, 2000.

FIGURE 1.5. Moe’s Books in Berkeley, California, one of more than twenty bookstores in that city. The presence of unusual numbers of bookstores is evidence that college towns are more highly educated than other places. Photograph by Syzmek Surma, 2007; used with permission.

College town residents are more likely to work in white-collar jobs. Although a few college towns still possess factories, most college towns have little heavy industry. In many, such as Bloomington, Indiana, manufacturing declined dramatically following World War II, as college enrollments increased, college towns became more dependent on education for their economic survival, and civic leaders grew more selective about the types of businesses they sought to attract. Workers in the study towns on average were half as likely as the U.S. population to work in manufacturing in 2000; just 7.2 percent did so. Nearly half of study town residents on average worked in managerial and professional jobs in 2000. More than a quarter were employed in education in 2000, three times the national rate. Many college towns resemble company towns in that a large percentage of adults work for a single employer. Southern Illinois University, for example, employed more than 5,000 people on its Carbondale campus in 2005, half the total labor force of the city.6

College towns are comparatively affluent. By most measures, college towns are prosperous and unusually stable economically. The median family income in the study towns in 2000, for example, averaged nearly $10,000 higher than similarly sized urban places nationwide.7 Because colleges are supported by state appropriations, endowment income, and tuition revenues that fluctuate less than the economy, college towns are somewhat insulated from economic downturns. Indicative of the economic stability of college towns were their low unemployment rates as the country emerged from its most recent recession. In April 2002, the five metropolitan areas with the lowest unemployment rates in the country, and thirteen of the top twenty-six, were small cities with major universities, such as College Station, Texas, and Charlottesville, Virginia. Further evidence that college towns are less susceptible than other places to economic crisis came in 2007, when the subprime-lending fiasco threatened to plunge the United States into another recession. University cities were discovered to have fewer high-cost home loans than other urban areas. College towns also perform well by other measures. Retail sales per capita in the study towns in 2002, for instance, averaged 20 percent higher than in the nation as a whole. As the U.S. economy shifts to knowledge-based industry, college towns are also well positioned for growth. Employment grew 20 percent faster in the study towns on average than in the country during a recent twelve-month period.8

These numbers do not tell the whole story, however. Per capita income in college towns is comparatively low because many students do not work or work low-wage, part-time jobs. Poverty rates in college towns are unusually high for that reason, though these numbers are deceptive since they do not likely consider all income sources. Nearly one quarter of study town residents in 2000 on average lived below the federal poverty line, twice the national rate and higher than chronically depressed regions such as Appalachia. Although some students are truly poor, poverty data do not accurately reflect the well-being of students, since many are supported by families. More troubling is the presence in college towns of unusual concentrations of unemployed or underemployed college graduates, typically the partners of professors, so-called trailing spouses. Colleges offer high incomes for professors and administrators, but career options for other college graduates in college towns are often limited.9

College town living costs, especially for housing, are high. Because family incomes in college towns are high and local governments are sometimes restrictive about development, living can be expensive. The overall cost of living in the study towns in June 2005 averaged 2.4 percent higher than the country. Housing costs averaged 4.5 percent higher. Those numbers are somewhat deceiving. They are unduly influenced by a few college towns where living costs are especially pricey. Living costs are greatest in college towns with elite colleges, particularly those within commuting distance of big cities, such as Princeton, New Jersey, and Boulder, Colorado. The average house price in 2005 was $628,000 in Princeton and $546,350 in Boulder. Most college towns are more reasonably priced. A Coldwell Banker survey in 2005 found that home prices in fifty-nine markets with major universities—including many college towns—were 19 percent less than they were nationwide. Prices are cheapest in isolated college towns like Manhattan, Kansas, where the average home price was $185,850. Many academics aspire to live in an Ann Arbor or a Berkeley, but a professor’s salary, comfortable but rarely huge, buys more in less desirable college towns.10

College towns are transient places. Going away to college is a rite of passage that has deep roots in American culture, particularly among the middle and upper classes, and is one characteristic that distinguishes U.S. higher education from that in the rest of the world. Every year, millions of American teenagers leave home to attend college. Students also move frequently while in school and usually leave college towns as soon as they graduate. Professors, too, are relative gypsies, because universities rarely hire their own graduates and academic culture encourages scholars to study at multiple institutions. Moving vans and U-Haul trucks are probably a more common sight in college towns than in any other type of place. One-third of heads of households in the study towns in 2000, on average, had moved in the previous fifteen months, 75 percent more than in the nation overall. Study town residents on average were twice as likely as the U.S. population to have lived in a different state five years before. In most college towns, the majority of the population is from somewhere else. In Chapel Hill, site of the flagship campus of the University of North Carolina, nearly two-thirds of residents in 2000 were born in a different state.

Transience produces one of the most striking features of college town life. Because students arrive on campus in fall, return home at Christmas, travel at spring break, and leave every summer, college towns display a predictable seasonality. The pulse of a college town rises and falls with the academic calendar. In August, college towns come back to life after a sleepy summer as students return for the fall semester. Traffic mounts. Cars line up near dormitories. Rental trucks back up on lawns. The thump-thump-thump of a distant student stereo replaces the hum of cicadas. Sorority pledges parade from house to house near campus. Businesses that cater to students make last-minute preparations. Parking spaces fill. There’s a palpable energy to a college town at the dawn of another academic year as freshmen learn their way around and year-round residents readjust to life in a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- 1 Defining the College Town

- 2 The Campus as a Public Space

- 3 Fraternity Row, the Student Ghetto, and the Faculty Enclave

- 4 Campus Corners and Aggievilles

- 5 All Things Right and Relevant

- 6 Paradise for Misfits

- 7 Stadium Culture

- 8 High-Tech Valhalla

- 9 Town vs. Gown

- 10 The Future of the College Town

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About the Author

- Back Cover