eBook - ePub

The Global Farms Race

Land Grabs, Agricultural Investment, and the Scramble for Food Security

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Global Farms Race

Land Grabs, Agricultural Investment, and the Scramble for Food Security

About this book

As we struggle to feed a global population speeding toward 9 billion, we have entered a new phase of the food crisis. Wealthy countries that import much of their food, along with private investors, are racing to buy or lease huge swaths of farmland abroad. The Global Farms Race is the first book to examine this burgeoning trend in all its complexity, considering the implications for investors, host countries, and the world as a whole.

The debate over large-scale land acquisition is typically polarized, with critics lambasting it as a form of "neocolonialism," and proponents lauding it as an elixir for the poor yields, inefficient technology, and unemployment plaguing global agriculture. The Global Farms Race instead offers diverse perspectives, featuring contributions from agricultural investment consultants, farmers' organizations, international NGOs, and academics. The book addresses historical context, environmental impacts, and social effects, and covers all the major geographic areas of investment.

Nearly 230 million hectares of farmland—an area equivalent to the size of Western Europe—have been sold or leased since 2001, with most of these transactions occurring since 2008. As the deals continue to increase, it is imperative for anyone concerned with food security to understand them and their consequences. The Global Farms Race is a critical resource to develop that understanding.

The debate over large-scale land acquisition is typically polarized, with critics lambasting it as a form of "neocolonialism," and proponents lauding it as an elixir for the poor yields, inefficient technology, and unemployment plaguing global agriculture. The Global Farms Race instead offers diverse perspectives, featuring contributions from agricultural investment consultants, farmers' organizations, international NGOs, and academics. The book addresses historical context, environmental impacts, and social effects, and covers all the major geographic areas of investment.

Nearly 230 million hectares of farmland—an area equivalent to the size of Western Europe—have been sold or leased since 2001, with most of these transactions occurring since 2008. As the deals continue to increase, it is imperative for anyone concerned with food security to understand them and their consequences. The Global Farms Race is a critical resource to develop that understanding.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Global Farms Race by Michael Kugelman, Susan L. Levenstein, Michael Kugelman,Susan L. Levenstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Economy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The world is experiencing a land rush. Wealthy, food-importing countries and private investors are flocking to farmland overseas.

These transactions are highly opaque, and relatively few details have been made public. What is known, however, is quite striking—and particularly the scale of these activities. Back in 2009, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) estimated that 15 to 20 million hectares of farmland had been subject to negotiations or transactions over the preceding few years. In 2011, the International Land Coalition (ILC) presented data indicating that nearly 80 million hectares had been subject to negotiation with foreigners since 2001—an amount exceeding the area of farmland in Britain, France, Germany, and Italy combined. Also in 2011, the World Bank projected that about 60 million hectares’ worth of deals were announced in 2009 alone.1

By early 2012, the ILC’s estimates had soared to a whopping 203 million hectares’ worth of land deals “approved or under negotiation” between 2000 and 2010. Some projections have gone even further; a September 2011 Oxfam study contends that nearly 230 million hectares—an area equivalent to the size of Western Europe—have been sold or leased since 2001, with most of this land acquired since 2008.2

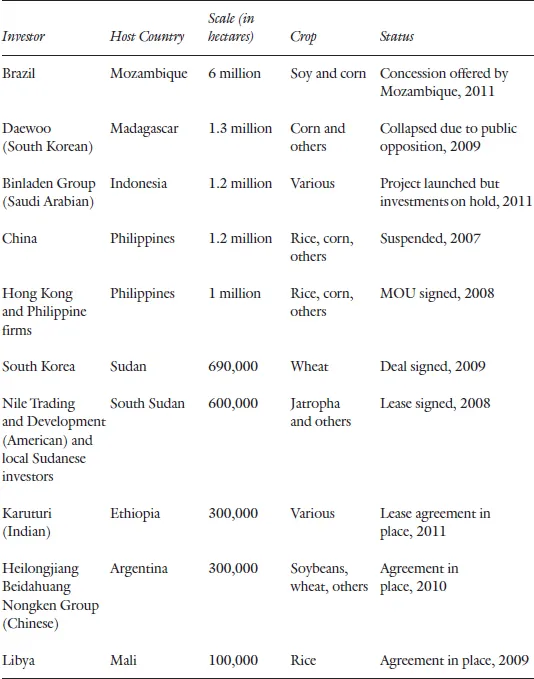

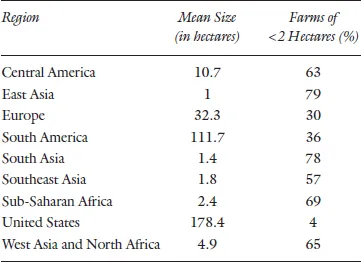

One of the largest and most notorious deals ultimately collapsed: an arrangement that would have given the South Korean firm Daewoo a 99-year lease to grow corn and other crops on 1.3 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar—half of that country’s total arable land. Popular opposition on the African island nation not only squelched the deal but also contributed to the demise of the government that had championed it. (Another mammoth bid, put forth by China to acquire up to a million hectares of land in the Philippines, was also unsuccessful.) However, other megadeals are reportedly in the works (see Table 1-1). Indonesia has opened up more than 1 million hectares of farmland to investors, while Mozambique has offered Brazil a staggering 6 million hectares to grow several different crops.3 To get a sense of the magnitude of such deals, consider that most small farmers in the developing world own plots of less than two hectares (see Table 1-2).

Early characterizations of this trend portrayed capital-rich Arab Gulf states and the prosperous countries of East Asia preying on the world’s farmland. In 2009, one specialist estimated that by the end of 2008, China, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, Japan, and Saudi Arabia were controlling over 7.6 million cultivable hectares overseas—more than five times the usable agricultural surface of Belgium.4

However, such assessments do not capture the whole picture—one that has more fully emerged only since 2011, when organizations such as the World Bank, Oxfam, and the ILC began releasing in-depth research. It is not simply the richest countries targeting the developing world; North African countries are investing in sub-Saharan Africa, Brazilian and South African investors are angling for deals worldwide, and Southeast Asian countries are eying one another’s soil. Meanwhile, keen interest in Australian and New Zealand farmland explodes the myth that these land acquisitions represent an assault solely on the soils of the developing world.

Additionally, the role of the United States often goes unreported. According to researchers and media reports, the US firm Goldman Sachs has purchased poultry and pig farms in China; American farmers have bought plots in Brazil; and North American investors hold 3.3 million hectares in Africa. In 2011, the Oakland Institute alleged that American universities—including Harvard and Vanderbilt—were investing heavily in African farmland through European hedge funds and financial speculators.5

The New Farms Race: Roots and Reasons

Why are we now witnessing this race for the world’s farmland, and what propels its participants? A chief reason is food security.

In 2008, world food prices reached their highest levels since the 1970s. The skyrocketing costs of staple grains and edible oils triggered riots across the globe—particularly in the impoverished cities of the developing world, where many people spend up to 75 percent of their incomes on food. Some top food-exporting nations, in efforts to prevent food price spikes and public unrest at home, imposed bans on food exports. Such bans, by taking large amounts of grain supplies off the global market, exacerbated the food insecurity of food-importing nations dependent on such staples.

TABLE 1-1 The 100,000-Hectares-and-Above Club: Ten of the Largest Land Deals

This information is largely derived from media reports. Its accuracy cannot be confirmed, and the status of these deals may have changed by the time of publication.

TABLE 1-2 Farm Sizes Worldwide

Source: World Bank, Rising Global Interest in Farmland, 2011

Prices have now stabilized and the world food crisis has receded from the media spotlight. However, food costs are still high and commodities markets remain unpredictable. Additionally, other factors—such as eroding topsoil, farmland-displacing urbanization, water shortages, and the spread of wheat-destroying disease—demonstrate the challenges nations and their populations continue to face in meeting their food needs. Indeed, food security remains an urgent global concern—and particularly for agriculturally deficient, water-short nations that depend on food imports to meet rapidly growing domestic demand.

Some of these nations have decided to take matters into their own hands. In an effort to avoid the high costs, supply shortages, and general volatility plaguing global food imports, these countries are bypassing world food markets and instead seeking land overseas to use for agriculture. Crops are harvested on this land and then sent back home for consumption.6

Energy security is another prime impetus. In an effort to avoid environmentally damaging and geopolitically risky hydrocarbons, many nations are searching feverishly for land overseas to use for biofuels production. In fact, according to the ILC, 40 percent—about 37 million hectares—of the world’s land involved in agricultural deals is set aside for this purpose (keep in mind, however, that some biofuels crops, such as oil palm, soybeans, and sugarcane, can produce food as well as fuel).

Meanwhile, private-sector financiers recognize land as a safe investment in an otherwise shaky economic climate, and they hope to capitalize financially on the mushrooming food- and energy-security-driven demand for agricultural land. Estimates from early 2012 judged that $14 billion in private capital was committed to investment in farmland—a figure projected to double by 2015. Nearly 200 private equity firms are projected to be involved in farming, with just 63 of them seeking to generate $13 billion in agricultural investments.7

Far from being coerced into these land deals, many developing-country governments welcome them—and even lobby aggressively for them. Pakistan, for example, has staged “farmland road shows” across the Arab Gulf to attract investor interest, offering lavish tax incentives and even a 100,000-person-strong security force to protect investors.8 Host governments hope that heavy injections of foreign capital will enhance agricultural technology, boost local employment, revitalize sagging agricultural sectors, and ultimately improve agricultural yields. They are also drawn to the new roads, bridges, and ports that some land investors promise to build. With such tantalizing incentives, many host-nation governments have no compunction about holding farmland fire sales.

Why This Book?

The global run on agriculture has sparked high levels of passion and polarization. Some regard it as the spark for a new green revolution—while others perceive it as a “new colonialism” or a “land grab,” whereby powerful forces seize land long held (or used) by the more vulnerable. Indeed, supporters believe these capital-intensive, technology-heavy deals, by boosting agricultural productivity, can help bring down global grain costs and reduce the threat of future food crises. Critics, conversely, worry about pernicious impacts on small farmers, their land, their livelihoods, and the environment. Some argue that the deals’ purported benefits could become moot if they result in mass displacements, land degradation, and natural resource shortages.

A more accurate picture can likely be found somewhere in between these two positions, and serious work on the topic must engage this middle ground. While such literature has begun to emerge, thanks to the output of organizations such as IFPRI, the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), the World Bank, and the ILC, the knowledge vacuum remains considerable, particularly in the United States.9 This book’s contribution to this new yet growing debate is to present a range of views on an equally broad array of issues flowing from the world’s pursuit of farmland.10 The Global Farms Race features contributions from agricultural investment consultants, farmers’ groups, international organizations, and academics based in nine different countries across the developed and developing worlds. Its topical scope encompasses historical dimensions, environmental implications, and social effects. It provides regional perspectives covering all the major areas of investment: Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the former Soviet Union/Eastern and Central Europe.

The book’s underlying argument is a simple one: Whether we support them or not, large-scale land acquisitions are a reality. We should accept this reality and seek to learn more about these deals with a spirit of inquiry that steers clear of undue alarmism and Pollyannaism alike. This is why even the chapters most critical of the deals do not issue shrill calls for their elimination, and why the most supportive chapters openly acknowledge that farmland investments are fraught with risks and challenges. The book deals with a topic that begs for more public debate, and for such debate to be healthy, it must not be contaminated with the poison of polarization.

With this in mind, the objective of The Global Farms Race is to equip readers with the proper grounding to understand the scramble for the world’s soils—a trend with considerable implications for major twenty-first-century challenges such as food security, natural resource management, and climate change.

History Reinventing Itself

While often referred to as a new trend, today’s land lust is simply the reappearance—in a new form—of a phenomenon that has occurred for centuries. In the nineteenth century, European colonialism gobbled up global farmland. In the early twentieth century, foreign fruit companies appropriated farmland in Central America and Southeast Asia. Later in the same century, Britain attempted (unsuccessfully) to convert present-day southern Tanzania into a giant peanut plantation. Indeed, the nightmare scenario invoked by critics of today’s foreign land acquisitions—a wealthy nation whisking its newly grown crops out of a famine-scarred country—has a historical precedent: During the Irish potato famine of the nineteenth century, the British government was exporting fresh Ireland-grown crops back home to England.

Derek Byerlee’s opening chapter surveys large-scale land acquisitions since the second half of the nineteenth century (the first era of globalization), with a focus on the six commodities that have dominated these deals over the last 150 years—sugarcane, tea, rubber, bananas, palm oil, and (more recently) food staples. Many of his examples involve the United States: American sugar companies acquiring Cuban forest and pasture land in the early 1900s, transforming the newly independent nation into the world’s leading sugar exporter; powerful US landholding sugar firms in Hawaii contributing to the annexation of the territory in 1898; and the United Fruit Company controlling nearly 1.5 million hectares of banana plantations in Central America in 1935, “making it the largest farmland holder in the world at that time.” He also describes how, in colonial-era Kenya, 3 million hectares of “prime” land were converted into European tea estates, displacing locals and helping spark the 1950s Mau Mau uprising; how a precursor company to Unilever obtained a 140,000-hectare concession to produce palm oil in early twentieth-century Belgian Congo; and how Nikita Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands program of the 1950s plowed up 55 million hectares of the Central Asian steppe.

Byerlee, an independent adviser who coauthored the World Bank’s 2011 Rising Global Interest in Farmland report, argues that despite this proliferation of large-scale deals, smallholders still managed to thrive. Even with colonial policies favoring estate production, he notes, smallholders produced half of Asia’s rubber in 1940. Meanwhile, the tea sector experienced “a remarkable transition from foreign-owned plantations to a robust smallholder sector,” a shift attributable to supportive government policies, smallholder innovation, and “forward-looking” companies. “The historical experience has shown the importance of providing a level playing field for smallholders,” Byerlee concludes, asserting that once support services are put into place, smallholders can “dominate” their respective industries.

Byerlee emphasizes that today’s overseas land investments do differ from their predecessors in significant ways—particularly in that the “high social costs” of past deals were more frequently tied to labor issues (such as poor working conditions) than to the land-related issues (such as displacement) witnessed today. He attributes this relative infrequency of land tensions to the fact that in the past, most land was acquired in sparsely populated areas. One can identify other differences as well: today the scale of the acquired land is much larger; the investments emphasize staples instead of cash crops; the deals are concluded on the basis of agreements instead of through the barrel of a gun; and they are spearheaded by more government-led investment than in the past.

David Hallam’s contribution provides a broad overview of international agricultural investments, focusing on trends, motivations, impacts, and policy implications. Hallam, of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), first provides a reality check. The number of implemented investments, he notes, “appears to be less” than what the media are reportin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- About Island Press

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Are We Learning from History?

- Chapter 3. Overview

- Chapter 4. Social and Economic Implications

- Chapter 5. Environmental Impacts

- Chapter 6. Investors’ Perspectives

- Chapter 7. Improving Outcomes

- Chapter 8. Regional Perspectives: Africa

- Chapter 9. Regional Perspectives: Asia

- Chapter 10. Regional Perspectives: Latin America

- Chapter 11. Regional Perspectives: Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union

- Chapter 12. Recommendations and Conclusion

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

- Appendix III

- Notes

- About the Editors

- About the Contributors

- Index

- Island Press | Board of Directors