![]()

Chapter 1

Green Neighborhoods

Traditional building forms and settlement patterns are the product of dialogues among natural and cultural processes.

A.W. Spirn, “New Urbanism and the Environment”

Even very large cities grow in small increments. The term “neighborhood” is frequently used to describe the urban “building blocks” of complementary land uses, transportation networks, services, and amenities.These systems are typically conceived together to benefit from the identity and location afforded by being in the same “neighborhood” as well as to leverage the substantial investment of land, capital, infrastructure, and human will it takes to create them. Cliff Moughtin quotes Boyd: “A neighborhood is formed naturally from the daily occupations of people, the distance it is convenient . . . to walk . . . to daily shopping . . . and a child to walk to school. He should not have a long walk and he should not have to cross a main traffic road. The planning of a neighborhood starts from that.”1

While “neighborhood” can be defined in diverse ways, the term is used in this book in a spatial sense of sharing common proximity and boundary. Understood this way, neighborhoods are those broadly legible, if not precisely definable, areas of cities in which people say they live, work, learn, or play. It is also the scale at which new areas of many cities are planned. Within this definition, neighborhoods may vary substantially in physical size, shape, population, density, or character. Several may link together to form a larger, interdependent group of neighborhoods. In contemporary usage, that proximity has frequently come to be defined as the distance that one can (or would be willing to) walk to services or to a transit stop (between five and ten minutes, or one-quarter to one-half mile for most people).That represents a land area of roughly 125 to 500 acres. Neighborhoods also have edges or boundaries that differentiate one from another. These edges can vary in type and character. Some may be hard and explicit (such as a wide, heavily trafficked street), whereas others may be soft and implicit (such as a contrasting land use or a common open space), allowing several neighborhoods to overlap or interconnect along a shared edge (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Diagrammatic neighborhood structure of Renaissance Florence. (Source: derived from Frey, Designing the City, p. 39)

Taken together, domain and edge are the physical conditions of a neighborhood in planning and urban design. Nineteenth-century British urban theorist Ebenezer Howard and architects Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker, who gave physical form to Howard’s theories, recognized the importance of these attributes of neighborhood.They shaped the Garden City, a new-town planning concept, around a “ward”—a district or quarter centered around the social institution of a school and separated from others by a greenbelt.2 The eleven British new towns authorized by the New Towns Act of 1946—for example, Runcorn and Ipswich—are defined by the following: a ten- to fifteen-minute walking distance from the farthest home to the school; a population that supports an elementary school and local services; a clearly defined boundary (typically reinforced by landscape); a center; through traffic relegated to perimeter streets; and an architectural treatment that distinguishes it from other neighborhoods.

In the United States, Clarence Perry’s 1929 essay on the neighborhood unit borrowed many themes from Howard. Perry argued that a neighborhood should be approximately 160 acres and should support a density of ten households per acre. The resulting population would support an elementary school (located at a central focal point of community services) and commercial services (located along edges with other neighborhoods). Several smaller parks and recreation areas would make up 10 percent of the land area. Neighborhood shape should be such that all households were within walking distance (less than half a mile) of a school and services. Neighborhood boundaries should follow major streets to keep high-volume traffic at the edges, reducing traffic through the neighborhood. Residential streets interior to the neighborhood could be smaller, with less automobile traffic. Only a few should connect directly to larger boundary streets.3

Perry’s work eventually led to national neighborhood planning standards published in the industry-wide technical bulletins of the U.S. Federal Housing Administration.4 After World War II, qualification for federal mortgage assistance was directly tied to these standards; thus they explicitly influenced the development pattern of a generation of subdivisions throughout the United States in the 1950s and 1960s.5

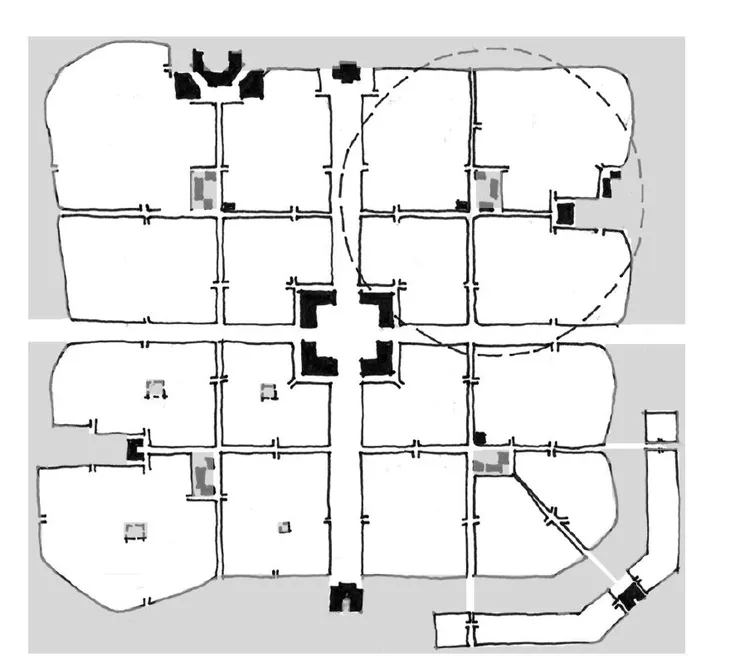

Perry’s work and its antecedents have informed neighborhood planning and design practice for almost eighty years. From the planning and urban design work of Perry’s contemporary Clarence Stein to the contemporary town-making principles of the Congress for the New Urbanism, planners, landscape architects, and architects have adapted and built upon his ideas and concepts (Figure 1.2). A comparison of Clarence Perry’s 1929 principles of neighborhood planning with those of Duany and Plater Zyberk (1997) show extensive agreement. For both, the preferable size is a 160-acre area bounded by larger scale streets and developed at densities sufficient to support an elementary school. Exact shape is not essential but should fit within a quarter-mile (5-minute walk) circle such that all sides are roughly equidistant from the center.

Figure 1.2 Comparison of (a) Clarence Perry’s (1929) and (b) Duany and Plater-Zyberk’s (1997) prototypical neighborhood plans (after Congress for the New Urbanism, 2000, p. 76)

- Neighborhood institutions only at community center in the Perry version, Shops and institutions near a transit stop in the DPZ version.

- Apartments and shopping districts at higher traffic intersections. Parking lots double as plazas in the DPZ version.

- Narrow interior streets configured for easy access to shops and community center. A mixed use street is anchored by shopping districts in the DPZ version.

- Civic buildings occupy prominent sites. A shopping district could substitute for a perimeter church site in the Perry version.

- A school and related recreation spaces may be located near the edge where it can be shared with an adjacent neighborhood.

- A playground is located in each quadrant.

- Boulevard edges may develop with (a) the short faces of traditional blocks; (b) workshops and offices; (c) a parkway corridor.

- Street and block patterns connect to adjacent neighborhoods to greatest extent possible.6

To Clarence Perry’s 1929 principles of the neighborhood unit, New Urbanists such as Duany and Plater-Zyberk have added several that address the urban design and architecture of neighborhoods. Still missing are principles that address environmental factors.

Figure 1.3 An aggregation of neighborhoods forming a village bounded by open space. (Source: derived from Duany and Plater-Zyberk, Towns and Town-Making Principles, 1991, p. 90)

Defining Green Neighborhoods

Many attributes embedded in the spatial models of neighborhood mentioned above offer the opportunity to improve urban environmental quality. Principles of the new urbanism, for example, generate development patterns that use land more economically than does prevailing contemporary practice. Densities are sufficiently high and land uses sufficiently mixed to increase the likelihood that daily services (stores, recreation, and schools, for example) are within walking distance. Street networks are sufficiently connective to encourage fewer automobile trips (and thus improve air quality and energy conservation) through choice of mode. Streets that make up the network are typically skinny—they are scaled and designed for equity of use among cars, bicycles, and pedestrians.Walking or bicycling becomes a viable alternative to driving for travel within the neighborhood, and transit becomes a viable option for travel outside the neighborhood.7

Less explicit and integral, however, are places for nature. More often, natural areas have limited or peripheral roles, typically as edges or boundaries to neighborhoods. Such roles increase the real and perceived barriers between natural and urban systems as well as weaken opportunities to integrate urban and natural functions. A more “green” model would create explicit places for nature and ecological functions, integrate them with the development pattern, and balance the competing spatial demands of open space, streets, and land uses within.

How might nature become more integral with urban development? For the sake of argument, assume that natural spaces are most often the open spaces of an urban pattern. Urban planner and observer Kevin Lynch has argued that open space is distributed in relatively few spatial patterns. In his lexicon, three patterns exist (Figure 1.4): the greenbelt (open space encloses urban development—an edge), the green wedge (open space radiates from a center), and the green network (a more broadly distributed but linked pattern of open space).8 These patterns represent contrasting points...