- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the middle of the Mojave Desert, Las Vegas casinos use billions of gallons of water for fountains, pirate lagoons, wave machines, and indoor canals. Meanwhile, the town of Orme, Tennessee, must truck in water from Alabama because it has literally run out.

Robert Glennon captures the irony—and tragedy—of America's water crisis in a book that is both frightening and wickedly comical. From manufactured snow for tourists in Atlanta to trillions of gallons of water flushed down the toilet each year, Unquenchable reveals the heady extravagances and everyday inefficiencies that are sucking the nation dry.

The looming catastrophe remains hidden as government diverts supplies from one area to another to keep water flowing from the tap. But sooner rather than later, the shell game has to end. And when it does, shortages will threaten not only the environment, but every aspect of American life: we face shuttered power plants and jobless workers, decimated fi sheries and contaminated drinking water.

We can't engineer our way out of the problem, either with traditional fixes or zany schemes to tow icebergs from Alaska. In fact, new demands for water, particularly the enormous supply needed for ethanol and energy production, will only worsen the crisis. America must make hard choices—and Glennon's answers are fittingly provocative. He proposes market-based solutions that value water as both a commodity and a fundamental human right.

One truth runs throughout Unquenchable: only when we recognize water's worth will we begin to conserve it.

Robert Glennon captures the irony—and tragedy—of America's water crisis in a book that is both frightening and wickedly comical. From manufactured snow for tourists in Atlanta to trillions of gallons of water flushed down the toilet each year, Unquenchable reveals the heady extravagances and everyday inefficiencies that are sucking the nation dry.

The looming catastrophe remains hidden as government diverts supplies from one area to another to keep water flowing from the tap. But sooner rather than later, the shell game has to end. And when it does, shortages will threaten not only the environment, but every aspect of American life: we face shuttered power plants and jobless workers, decimated fi sheries and contaminated drinking water.

We can't engineer our way out of the problem, either with traditional fixes or zany schemes to tow icebergs from Alaska. In fact, new demands for water, particularly the enormous supply needed for ethanol and energy production, will only worsen the crisis. America must make hard choices—and Glennon's answers are fittingly provocative. He proposes market-based solutions that value water as both a commodity and a fundamental human right.

One truth runs throughout Unquenchable: only when we recognize water's worth will we begin to conserve it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unquenchable by Robert Jerome Glennon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Crisis

CHAPTER 1

Atlanta's Prayer for Water

“Water sustains all.”

—Thales of Miletus, 600 BC

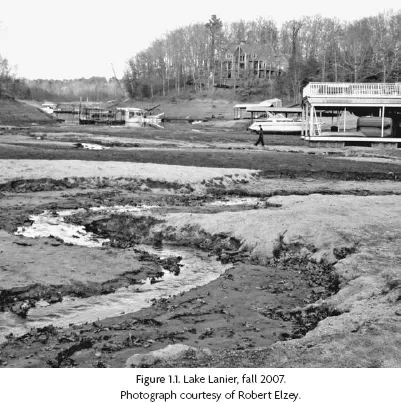

IN OCTOBER 2007, Atlanta's watershed commissioner, Rob Hunter, issued a dire warning: if it didn't rain, Atlanta would run out of water in four months. His was the optimistic estimate. Other federal and state officials predicted that Lake Lanier, the principal water supply for almost 5 million people in Metro Atlanta, could go dry in three months. A sustained two-year drought had dropped the lake's level by fifteen feet, leaving docks and boathouses high and dry, exposing tree stumps not seen since the lake was first filled, fifty years earlier, and creating red mudflats below what used to be swimming beaches. And Lake Lanier is not some dinky puddle: its surface covers 38,000 acres, almost twice the size of Manhattan. Lanier is one of America's favorite lakes—more than 7.5 million people a year enjoy boating, fishing, waterskiing, and jet skiing as they patronize its marinas, water parks, and resorts. Vacation homes crowd the 692 miles of shoreline.

As Lanier's waters shrank, Georgia announced a Level 4 drought emergency and banned all outdoor watering except for agricultural and “essential” business uses. Governor Sonny Perdue ordered North Georgia businesses and utilities to cut water use by 10 percent. Atlanta's mayor, Shirley Franklin, begged of her constituents, “This is a not a test. Please, please, please do not use water unnecessarily.” Concerned about water supplies, the Paulding County Board of Commissioners, in Metro Atlanta, imposed an indefinite ban on new rezoning requests. The development community went bonkers. Michael Paris, head of a pro-growth organization, argued that telling developers to stop building would be like telling Metro Atlanta families to stop having children because there's no more water. “That's how silly [halting development] is,” said Paris.

The restrictions caught the business community by surprise. Sam Williams, president of the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, called the drought the top threat to Atlanta's economy and warned it could be a “dress rehearsal” for what the future holds. The Coca-Cola Company has a major presence in Atlanta, as does PepsiCo, with a Gatorade plant that is the largest water user in Atlanta. Bruce A. Karas, Coca-Cola's vice president for sustainability, sounded an alarm. “We're very concerned. Water is our main ingredient. As a company, we look at areas where we expect water abundance and water scarcity, and we know water is scarce in the Southwest. It's very surprising to us that the Southeast is in a water shortage.”

In Georgia, as in the rest of the United States, water is essential not only to human life. It is vital to the entire economy, not just for companies such as Coca-Cola and Kellogg but also for less obvious industrial operations, including automobile manufacturers; steel plants; copper, gold, and coal mines; defense industries; and semiconductor manufacturers, as well as for the energy sector, which includes oil and gas companies, refineries, power plants, and hydroelectric generating facilities. We may worry loudly about the price of oil, but water is the real lubricant of the American economy.

This is most evident in high-growth states such as Georgia. The largest state east of the Mississippi River, Georgia is blessed with extraordinary water resources: 70,000 miles of streams, 400,000 acres of lakes, 4.5 million acres of wetlands, an additional 384,000 acres of tidal wetlands, 854 square miles of estuaries, and 100 miles of coastline, all nourished by an average annual rainfall of forty-nine inches. Georgia's problem comes not from a lack of water but from uneven distribution of the water. Most of it is in the southern part of the state, whereas Atlanta (and most of the state's population) is in the northern part.

As one of the fastest-growing states in the country, with a population approaching 9 million, Georgia expects to be home to another 2 million people by 2015. Population in Metro Atlanta is expected to increase by 50 percent by 2030. To grasp these statistics, consider Atlanta's traffic congestion woes. Metro Atlanta has sprawled in all directions, gobbling up fifty-five acres a day, with the city itself in the middle, constricting the movement of commuters from one side to another. Commuting time has grown faster than in any other city. Traveling ten miles can take forty-five minutes, and some commutes involve fifty miles each way. A portion of Interstate 75 that skirts Atlanta is currently fifteen lanes wide, putting it at the top of the Federal Highway Administration's list of America's biggest highways, yet expansion plans will widen that section. Once completed, it will have twenty-three lanes and be 388 feet wide, more than the length of a football field.

As Georgia's population climbed from 3.4 million in 1950 to 8.2 million in 2000, the state's use of water rose from 150 million to 1.3 billion gallons per day. And in southern Georgia, an additional and unexpected change in water use has come from the rise of irrigated agriculture. Irrigation, once confined to the arid West, where artificial watering supplements natural rainfall, has spread as farmers in the Midwest, East, and Southeast have discovered that applying more water to their fields than Mother Nature provides can boost crop production. Center-pivot systems, those big circles that airplane passengers can see from 35,000 feet, have proliferated in central and southern Georgia. As a result, agricultural water use, mostly from groundwater, grew twelvefold between 1950 and 1980 and has doubled since then, to 1.1 billion gallons per day. A spike in acreage planted with corn, driven by the ethanol boom, is further increasing agricultural water use. Georgia's first ethanol refinery, operated by First United Ethanol, will require roughly 500 million gallons of water per year.

Georgia has also become a second-home haven for retirees from the North and for others who are increasingly choosing Georgia over Florida. Seventy-five miles east of Atlanta is Lake Oconee, an enormous reservoir created in 1979 by Georgia Power to serve a hydroelectric plant. The area is booming, with more than 100 subdivisions and developments featuring gated communities with lushly watered golf courses. Homes, from one-bedroom condominiums to immense estates, line the 374 miles of shoreline. The major developers have plans for thousands of new homes.

The turf industry satisfies Georgia homeowners' demand for impeccably manicured lawns. Indeed, much of the increase in agricultural irrigation comes from more than two dozen turf farms that grow grass for Atlanta's suburbs. With typical American impatience, new homeowners don't want to plant grass seed when they can have mature lawns rolled out in sheets before they move in. As the drought in North Georgia continues and as watering bans take their toll on existing lawns, one perverse result will be the use of more water to grow turf. As Georgia's state geologist, Jim Kennedy, explained, sod production will increase “because when your lawn dies, you will need to replace it.” Georgia developers also find imaginative ways to use water, including building artificial lakes in subdivisions to induce waterskiing enthusiasts to buy homes. “Atlanta's unrestrained growth and cavalier attitude to water use has got to be on the table,” complained Sally Bethea, executive director of Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, an organization dedicated to protecting the river.

But rather than confront the problem at its core, as the drought worsened, Governor Sonny Perdue played the blame game, claiming that Atlanta's water woes were due to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers releasing too much water from Lake Lanier to protect three endangered species—two types of mussel and the Gulf sturgeon—that live downstream in the Apalachicola River in Florida. On top of the natural drought, Perdue asserted, “we are mired in a man-made disaster of federal bureaucracy.” The governor asked a federal court to issue an injunction to halt the releases from Lanier. He also appealed to President George W. Bush to grant emergency drought relief and to use his powers to exempt Georgia from the Endangered Species Act. Meanwhile, Georgia's United States senators, Johnny Isakson and Saxby Chambliss, as well as members of its congressional delegation, introduced legislation to create a temporary exemption from the act. “Blaming the endangered fish and mussels for our water woes,” a University of Georgia ecology professor responded, “is as silly and misdirected as blaming the sick canary for shutting down the mine.”

Things had become so dire by November 2007 that Governor Perdue tried another tack. Outside the Georgia Capitol, he led several hundred ministers, legislators, landscapers, and office workers in prayers for rain. Holding Bibles and crucifixes, the group linked arms and sang “What a Mighty God We Serve” and “Amazing Grace.” The governor repented, “Oh, Father, we acknowledge our wastefulness,” and promised that Georgians would do better in conserving water. The governor, not one to take chances, timed the prayer service to coincide with weather forecasters' predictions of the first rain-bearing front in months.

Georgia's downstream neighbors are angry about its water use. Florida's governor, Charlie Crist, and Alabama's governor, Bob Riley, asked President Bush to reject Governor Perdue's request for emergency relief. Riley called any reduction in releases from Lake Lanier “a radical step that would ignore the vital downstream interests of Alabama.”

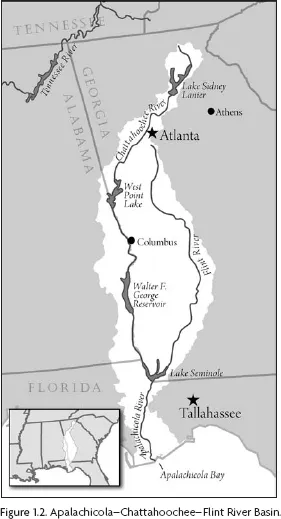

The three states have been locked in a bitter fight over water since 1990, when Florida and Alabama filed federal lawsuits to stop Metro Atlanta from taking more water from Lake Lanier. In 1997, the three states reached an agreement, known as the Apalachicola–Chattahoochee–Flint River Basin Interstate Compact (ACF), which was nothing more than a mandate for them to develop a formula for allocating the waters of the three rivers by 1998. That never happened. The negotiations collapsed because Georgia had no incentive to curb its water use. As the upstream state, it has physical control over the water. If Georgia holds back water for its own use, there is nothing—short of war or litigation—that Florida and Alabama can do about it. Thus, in 2004, amid much finger-pointing, Florida and Alabama revived their 1990 lawsuit and the three states went back to court. The three governors seemed to reach a truce in November 2007, when they agreed to settle their differences by February 15. This agreement prompted one cynic to jest, “Of what year?” Indeed, a week after the governors' meeting, Florida backed away from the truce in the tristate water war.

When the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decided, in November 2007, that it could temporarily reduce releases from Lake Lanier without jeopardizing the endangered species, Florida commenced new legal action. In February 2008, the U.S. Court of Appeals sided with Florida and Alabama in ruling that Georgia could not withdraw as much water as it wanted from Lake Lanier.

From Florida's vantage point, greater diversions from Lake Lanier mean lower flows downstream in the Apalachicola River. The fresh water plays a critical role in sustaining Florida's $134 million commercial oyster industry. Michael Sole, secretary of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, complained that cutting river flows would cause a “catastrophic collapse of the oyster industry in Apalachicola Bay” and “displace the entire economy of the Bay region.” Florida's concerns did not make much of an impression on Jackie Joseph of the Lake Lanier Association, who shrugged and said, “We have a $5.5 billion economy around this lake.”

Such attitudes have alienated people outside Metro Atlanta and even other Georgians. The Valdosta Daily Times editorialized: “Atlanta is a greedy, poorly designed behemoth of a city incapable of hearing the word ‘no' and dealing with it. Atlanta's politicians can't bring themselves to tell their greedy constituents complaining about the low flows in their toilets this week that perhaps if they didn't have six bathrooms, it might ease the situation a bit.”

Georgia has also squared off against Alabama over the Alabama-Coosa-Tallapoosa River Basin (ACT). Metro Atlanta gets a substantial amount of its water from Allatoona Lake, which impounds the waters of the Etowah River. The Etowah River eventually becomes part of the Coosa River before it flows into Alabama. From Alabama's perspective, water flows in the Coosa River are critical to its downstream businesses, including the Joseph M. Farley Nuclear Plant, which supplies 20 percent of Alabama Power's electricity. Georgia-Pacific Corporation paper mills and Gulf Power hydroelectric plants would also suffer from lower flows. As with the ACF negotiations, ACT negotiations haven't produced a solution.

Eventually, the United States Supreme Court may step in. It has sole jurisdiction over disputes between states, and, in a set of rulings that mostly involved western rivers, it has divided up interstate rivers. Most ominously from Georgia's perspective, the Supreme Court has ruled that it is “essentially irrelevant” whether the headwaters of a river begin in one state or another. It has not permitted upstream states to hoard water that their downstream neighbors need. A state's record of water conservation and efficiency may affect the Court's allocation. On this front, Georgia is vulnerable.

In a separate battle raging on the other side of the state, Savannah, Georgia, has incurred the wrath of Hilton Head, South Carolina. David Baize, assistant chief of South Carolina's Bureau of Water, notes that “the whole coastal region, including Savannah, is just the definition of sprawl.” Driving this growth is the Port of Savannah, the fourth-busiest and the fastest-growing container terminal in the United States. Target, IKEA, and Heineken recently opened distribution centers to take advantage of the port. Baize's agency is charged with issuing permits for groundwater wells in South Carolina, including for the Hilton Head area, a popular tourist destination. Before Savannah's increase in development, groundwater flowed through the Upper Floridan Aquifer and discharged into the ocean at Port Royal Sound in South Carolina. The Savannah area uses six times the groundwater that Hilton Head does, and its collective pumping has reversed the direction of the flow of groundwater. The gradient created by the pumping has caused salt water to migrate laterally and contaminate freshwater wells.

Richard Cyr, general manager of the Hilton Head Public Service District, notes that the utility had to shut down five of its twelve wells because chloride levels, as a result of saltwater migration, exceeded the maximum federal contaminant level. Because Savannah's wells are in a deeper part of the aquifer, which the salt water has yet to reach, Savannah has thus far avoided Hilton Head's fate. “We're the damaged party in this,” says Baize. “It is our wells that are being lost and it is our aquifer that's being contaminated.” South Carolina considered litigation but decided that the money would be better spent seeking alternative water sources. But this water won't come cheaply. According to Cyr, the two utilities that serve Hilton Head have spent $90 million constructing a reverse osmosis saltwater desalination plant to offset their loss of water from the Floridan Aquifer.

In 2008, reduced flow in the Savannah River led the Nuclear Regulatory Commission's Atomic Safety and Licensing Board to withhold approval of Southern Nuclear Operating Company's request to build two new reactors that would withdraw as much as 83 million gallons per day.

Even Tennessee is unhappy with Georgia's plans for finding more water. After Atlanta's mayor, Shirley Franklin, suggested piping in water from the Tennessee River, Tennessee's governor, Phil Bredesen, responded: “I would have a real problem with a wholesale transfer of water out of the Tennessee watershed.” If Georgia lawmakers have their way, that will soon happen. In 2008, the Georgia legislature passed a resolution claiming that an “erroneous” survey in 1818 mistakenly located the border between Georgia and Tennessee approximately one mile south of where it should be. If the border is moved northward, a bend in the Tennessee River would become part of Georgia, giving Georgia unfettered access to the river. On hearing of Georgia's desire to alter the boundary nearly two centuries after the survey, Governor Bredesen responded, “This is a joke, right?” Not in Georgia.

Even before the drought commenced, Georgia needed more water. Plans were already under way to divert an additional 126 billion gallons from the Chattahoochee and Etowah rivers and to build four more reservoirs and expand others, which collectively would hold an additional 33 billion gallons. Glenn Richardson, speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives, pledged his full support. “Frankly, we should have been doing this before now,” he said. But given that each and every one of these gallons would travel downstream if it weren't captured by Georgia, it is unlikely that Florida and Alabama will agree with the speaker. These increased withdrawals will severely compromise commercial and sport fisheries, recreation, wildlife habitat, and water quality. Water pollution, a serious problem in the Chattahoochee River near Atlanta, will worsen as increased withdrawals reduce the river's dilution capacity.

As Georgia confronts this severe drought, what is most striking is what the state is not doing: it is not restricting new uses. Georgia continues to approve water permits on a first-come, first-served basis. And that's only when permits are actually required. By state law, there is no need for a permit to divert water from a river or to pump water from a well unless the use exceeds 100,000 gallons a day. The consequence is a booming well-drilling business during one of the Southeast's worst droughts on record. “We could run seven days a week if we wanted to,” observes Wes Watson, owner of a small company that drills private and commercial wells. In Watkinsville, Dan Elder, another well driller, used to get three to five calls a week from prospective clients. Now he's getting that many calls a day, and he has a six-week backlog.

Even as conservation restrictions have kicked in, some Georgians want to enjoy the same lush landscapes and green lawns they did before the drought. As a result, the RainHarvest Company, a suburban Atlanta business that installs systems to capture rain, has seen its business quadruple during the drought. One of the company's founders, Paul Morgan, phil...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One. The Crisis

- CHAPTER 1. Atlanta's Prayer for Water

- CHAPTER 2. Wealth and the Culture of Water Consumption

- CHAPTER 3. Our Thirst for Energy

- CHAPTER 4. Fouling Our Own Nests

- CHAPTER 5. The Crisis Masked

- Part Two. Real and Surreal Solutions

- CHAPTER 6. Business as Usual

- CHAPTER 7. Water Alchemists

- CHAPTER 8. The Ancient Mariner's Lament

- CHAPTER 9. Shall We Drink Pee?

- CHAPTER 10. Creative Conservation

- CHAPTER 11. Water Harvesting

- CHAPTER 12. Moore's Law

- Part Three. A New Approach

- CHAPTER 13. The Enigma of the Water Closet

- CHAPTER 14. The Diamond—Water Paradox

- CHAPTER 15. The Steel Deal

- CHAPTER 16. Privatization of Water

- CHAPTER 17. Take the Money and Run

- CHAPTER 18. The Future of Farming

- CHAPTER 19. Environmental Transfers

- CHAPTER 20. The Buffalo's Lament

- CONCLUSION. A Blueprint for Reform

- EPILOGUE. The Salton Sea

- Acknowledgments

- List of Figures

- Sources

- Index