eBook - ePub

Collected Papers of Michael E. Soulé

Early Years in Modern Conservation Biology

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the early 1970s, the environmental movement was underway. Overpopulation was recognized as a threat to human well-being, and scientists like Michael Soulé believed there was a connection between anthropogenic pressures on natural resources and the loss of the planet's biodiversity. Soulé—thinker, philosopher, teacher, mentor, and scientist—recognized the importance of a healthy natural world and with other leaders of the day pushed for a new interdisciplinary approach to preserving biological diversity. Thirty years later, Soulé is hailed by many as the single most important force in the development of the modern science of conservation biology.

This book is a select collection of seminal writings by Michael Soulé over a thirty-year time-span from 1980 through the present day. Previously published in books and leading journals, these carefully selected pieces show the progression of his intellectual thinking on topics such as genetics, ecology, evolutionary biology, and extinctions, and how the history and substance of the field of conservation biology evolved over time. It opens with an in-depth introduction by marine conservation biologist James Estes, a long-time colleague of Soulé's, who explains why Soulé's special combination of science and leadership was the catalyst for bringing about the modern era of conservation biology. Estes offers a thoughtful commentary on the challenges that lie ahead for the young discipline in the face of climate change, increasing species extinctions, and impassioned debate within the conservation community itself over the best path forward.

Intended for a new generation of students, this book offers a fresh presentation of goals of conservation biology, and inspiration and guidance for the global biodiversity crises facing us today. Readers will come away with an understanding of the science, passion, idealism, and sense of urgency that drove early founders of conservation biology like Michael Soulé.

This book is a select collection of seminal writings by Michael Soulé over a thirty-year time-span from 1980 through the present day. Previously published in books and leading journals, these carefully selected pieces show the progression of his intellectual thinking on topics such as genetics, ecology, evolutionary biology, and extinctions, and how the history and substance of the field of conservation biology evolved over time. It opens with an in-depth introduction by marine conservation biologist James Estes, a long-time colleague of Soulé's, who explains why Soulé's special combination of science and leadership was the catalyst for bringing about the modern era of conservation biology. Estes offers a thoughtful commentary on the challenges that lie ahead for the young discipline in the face of climate change, increasing species extinctions, and impassioned debate within the conservation community itself over the best path forward.

Intended for a new generation of students, this book offers a fresh presentation of goals of conservation biology, and inspiration and guidance for the global biodiversity crises facing us today. Readers will come away with an understanding of the science, passion, idealism, and sense of urgency that drove early founders of conservation biology like Michael Soulé.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collected Papers of Michael E. Soulé by Michael E. Soulé in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781610915762Subtopic

Environmental Science1

Conservation Biology: Its Scope and Its Challenge

MICHAEL E. SOULÉ AND BRUCE A. WILCOX

from Conservation Biology: An Evolutionary-Ecological Perspective, 1980

Conservation Biology

Conservation biology is a mission-oriented discipline comprising both pure and applied science. This book is not the first in the field; there are other excellent texts (Dasmann, 1968; Ehrenfeld, 1970). In addition there are symposia with a more traditional approach, or which give specialized treatment to particular habitats, regions or to the status and management of particular taxa (for example, Duffey and Watt, 1971; Duffey et al., 1974; Schoenfeld et al., 1978; Prance and Elias, 1977).

In this book we have attempted to expand the range of topics covered and the depth with which they are usually treated. With regard to breadth, conservation biology is as broad as biology itself. It focuses the knowledge and tools of all biological disciplines, from molecular biology to population biology, on one issue—nature conservation. Among the contributors to this book, for example, are botanists, zoologists, ecologists, geneticists, evolutionists, a statistician, a mathematician-demographer, a cytologist, a biochemist, an endocrinologist, a sociobiologist and experts in the field of natural resources.

With regard to depth, conservation biology can and should be as profound, intellectually rigorous and challenging as any field, limited only by the capacities of its practitioners. As a science, it is not strictly “pure,” but neither is it purely “applied,” for most of the chapters in this book contain ideas, data and conclusions that will advance basic science. This is as good a test of originality and rigor as any.

Conservation has a venerable history of scientific (Leopold, 1933; Smith, 1976) and philosophical (Passmore, 1974; Singer, 1975) discourse. Man has sought to protect wildlife at least as far back as Ashoka (around 250 BC). Journalists, poets and scholars of every stripe have written copiously about nature—its values and how to save it from the human menace.

In spite of this scholarly and literary legacy we feel that conservation biology is a new field, or at least a new rallying point for biologists wishing to pool their knowledge and techniques to solve problems. A community of interest and concern is often crystalized by a simple term. Conservation biology is such a term.

Unfortunately, the emergence of conservation biology as a respectable academic discipline has been slowed by prejudice. Until recently, few academically oriented biologists would touch the subject. While wildlife management, forestry and resource biologists (particularly in the industrialized temperate countries) struggled to buffer the most grievous or economically harmful of human impacts (deforestation, soil erosion, overhunting), the large majority of their academic colleagues thought the subject was beneath their dignity. But academic snobbery is no longer a viable strategy, if it ever was. Because many habitats, especially tropical ones, are on the verge of total destruction and many large animals are on the verge of extinction, the luxury of prejudice against applied science is unaffordable. Conservation genetics is an example of such academic disinterest. This field has been one of the weakest in conservation biology. One of the purposes of this book is to begin correcting this handicap.

Given encouragement, a forum, and, one hopes, the funding, biologists will gladly enlist to help save the world’s rapidly expiring biota. As the table of contents will verify, “pure” scientists from many disciplines are eager to be conservation biologists. The issue that faces every student of biology today is not whether to be a conservationist, but how. Even if one rationalizes (as do many of our colleagues) that one’s esoteric research is far removed from nature in the raw, or from the plight of tigers, gorillas, redwoods and “jungles,” it seems to us that the study of life becomes a hollow, rarefied pursuit if the very animals and plants that fired our imaginations as children and triggered our curiosity as students should perish.

A Word on Economics

Conservation biology, strictly speaking, does not include the subject of economics.* For that reason, there are no chapters in this book on the acquisition or maintenance costs of reserves (but, see Chapter 18 and Chapter 11). As shown in Table 1, the industrialized countries have ten times the staff and ten times the money per unit area of national park as do the lesser developed countries. This gap in conservation support is serious enough, but the problem is compounded by the greater needs in many of the tropical countries, particularly in regions where poaching and other forms of encroachment require many skilled and dedicated wardens.

This is just another example of the well-known principle that scientific and technological expertise is worthless in the final analysis, if the money and resources required to implement the expertise is absent. Thus, the issue is not whether scientists should commit some of their time to public education and lobbying, but rather, how much of their time.

Comments on the Design of Nature Reserves

An issue that has been the subject of controversy (see Simberloff and Abele, 1975, 1976; Diamond, 1976; Whitcomb et al., 1976; Terborgh, 1976) and that is mentioned or alluded to by nearly every author in this book is the optimal design of nature reserves—the little fragments of landscape where Man expects to preserve nonhuman life.** Nature reserves are the most valuable weapon in our conservation arsenal (Chapter 11), so they deserve extra attention in this introductory discussion.

TABLE 1. National park budgets and personnel.

| Country | U.S. dollars/1000 ha | Staff/1000 ha |

| Industrialized | ||

| Australia | 433 | 0.042 |

| Canada | 48.5 | 0.135 |

| Japan | 975 | 0.358 |

| United States | 4239 | 0.350 |

| Brazil | 3782 | 3.500 |

| Mean | 1895 | 0.877 |

| Nonindustrialized | ||

| Congo | 39 | 0.026 |

| Ghana | 610 | 0.612 |

| Indonesia | 31 | 0.025 |

| Niger | 25 | 0.013 |

| Senegal | 311 | 0.082 |

| Thailand | 48 | 0.000 |

| Uganda | 163 | 0.017 |

| Zambia | 210 | 0.006 |

| Mean | 180 | 0.098 |

Data from Anon., 1977.

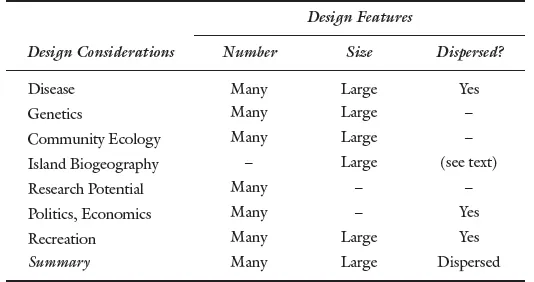

When considering the preservation of a particular biota, a system of nature reserves can be described by reference to three features: number of reserves, size of reserves and density (or proximity) of reserves. With regard to number and size, some biogeographers have argued that reserves should be large and not necessarily numerous; others have argued for many, smaller reserves. Nevertheless, all agree that the best solution from the biogeographical standpoint is many, large reserves. But there are other design considerations and factors besides biogeography that should influence reserve design. Table 2 lists these; it also tabulates our decisions regarding reserve size, number and proximity. This is a simplistic picture, but it has a purpose. It shows that all viewpoints (factors) converge on the same conclusion—reserves should be manifold, large and (for most purposes) dispersed, as is documented in the following comments.

Disease

Can epidemics destroy one or more species in a region the size of a nature reserve (Frankel and Soule, in press)? In recent years disease has eliminated many mammal species from large areas. These diseases include rinderpest, myxomatosis, anthrax, hoof and mouth disease, yellow fever and epidemic hemorrhagic disease. Botulism and avian cholera have devastated bird populations. Plant examples include chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease. The potential for disaster is aggravated by the susceptibility of domestic animals to most of the diseases that can plague wild species. Farms and villages with rabbits, sheep, cattle, swine and fowl will encircle most nature reserves in the near future, and these stocks will be a perennial source of contagion for the wild species.

TABLE 2. The components of nature reserve planning.

Another consideration is disease resistance. Small, isolated populations will tend to lose genetic variability, including resistance genes, resulting in a gradual increase in susceptibility to diseases. It is folly, then, to keep all of the individuals of a species in a single reserve regardless of size, unless, of course, several well isolated populations exist within a reserve—an exceptional situation. We do not mean that the prime directive of conservation should be maximizing the number and isolation of reserves. But if the choice is between (1) a single reserve containing the last vestiges of one or more valuable species versus (2) several (perhaps smaller) isolated reserves, each with representative populations of the desirable forms and appropriate habitat, common sense and history give the nod to the latter choice.

Community Ecology

The world is patchy and patches come and go. Even a region as superficially homogeneous as the Amazon Basin will require many reserves to maintain examples of all of its habitats (Chapter 5; Chapter 17). Frequent climatic and geologic disturbances as well as fire can affect entire small reserves (Chapter 5). Reserves must be designed with the largest disturbance type in mind (Chapter 2). Viable populations of high trophic level species, large herbivores and many tropical plants, as well as many butterfly species require large reserves (Chapter 2; Chapter 3). Finally, only large areas will contain a balance of successional stages necessary for the survival of many plants, insects and the animals that depend on them (Chapter 2).

Island Biogeography

Extinction rates in large reserves will be lower than those in small reserves, so it would seem that large reserves are superior. They also hold more species at equilibrium. On the other hand, if extinction rates, particularly for vertebrates, were generally very low (measured in geological rather than historic time), a large number of small, complementary reserves, each harboring a small but unique portion of the biosphere, would suffice. Extinction rates appear to be high (Chapter 6) so it is best to maximize both size and number. Proximity of reserves to one another is also important if it enhances recolonization and gene flow between reserves. But this rule only applies to species that normally traverse wide stretches of inhospitable habitat (those that fly or have efficient wind dispersal mechanisms). Even among flying species, however, only a small minority venture out of their normal habitat (Ehrlich and Raven, 1969; Diamond, 1971; 1976; Terborgh, 1974) and so only a fraction of species would benefit from proximity.

Research

Replication of reserves offers advantages for pure and applied research because it permits management experiments and other kinds of deliberate perturbation such as benign neglect, controlled burning or logging, removal of predators or dominant herbivores and the addition of species. Suc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Note from the Publisher

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Conservation Biology: Its Scope and Its Challenge

- 2 What Is Conservation Biology?

- 3 The Millennium Ark: How Long a Voyage, How Many Staterooms, How Many Passengers?

- 4 Conservation Biology and the “Real World”

- 5 Reconstructed Dynamics of Rapid Extinctions of Chaparral-Requiring Birds in Urban Habitat Islands

- 6 The Onslaught of Alien Species, and Other Challenges in the Coming Decades

- 7 Conservation: Tactics for a Constant Crisis

- 8 Conservation Genetics and Conservation Biology: A Troubled Marriage

- 9 The Social and Public Health Implications of Global Warming and the Onslaught of Alien Species

- 10 Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation

- 11 Conserving Nature at Regional and Continental Scales: A Scientific Program for North America

- 12 Ecological Effectiveness: Conservation Goals for Interactive Species

- 13 Strongly Interacting Species: Conservation Policy, Management, and Ethics

- 14 Editorial, The “New Conservation”

- Permissions and Original Sources