- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Every day, we are presented with a range of "sustainable" products and activities—from "green" cleaning supplies to carbon offsets—but with so much labeled as "sustainable," the term has become essentially sustainababble, at best indicating a practice or product slightly less damaging than the conventional alternative. Is it time to abandon the concept altogether, or can we find an accurate way to measure sustainability? If so, how can we achieve it? And if not, how can we best prepare for the coming ecological decline?

In the latest edition of Worldwatch Institute's State of the World series, scientists, policy experts, and thought leaders tackle these questions, attempting to restore meaning to sustainability as more than just a marketing tool. In State of the World 2013: Is Sustainability Still Possible?, experts define clear sustainability metrics and examine various policies and perspectives, including geoengineering, corporate transformation, and changes in agricultural policy, that could put us on the path to prosperity without diminishing the well-being of future generations. If these approaches fall short, the final chapters explore ways to prepare for drastic environmental change and resource depletion, such as strengthening democracy and societal resilience, protecting cultural heritage, and dealing with increased conflict and migration flows.

State of the World 2013 cuts through the rhetoric surrounding sustainability, offering a broad and realistic look at how close we are to fulfilling it today and which practices and policies will steer us in the right direction. This book will be especially useful for policymakers, environmental nonprofits, and students of environmental studies, sustainability, or economics.

In the latest edition of Worldwatch Institute's State of the World series, scientists, policy experts, and thought leaders tackle these questions, attempting to restore meaning to sustainability as more than just a marketing tool. In State of the World 2013: Is Sustainability Still Possible?, experts define clear sustainability metrics and examine various policies and perspectives, including geoengineering, corporate transformation, and changes in agricultural policy, that could put us on the path to prosperity without diminishing the well-being of future generations. If these approaches fall short, the final chapters explore ways to prepare for drastic environmental change and resource depletion, such as strengthening democracy and societal resilience, protecting cultural heritage, and dealing with increased conflict and migration flows.

State of the World 2013 cuts through the rhetoric surrounding sustainability, offering a broad and realistic look at how close we are to fulfilling it today and which practices and policies will steer us in the right direction. This book will be especially useful for policymakers, environmental nonprofits, and students of environmental studies, sustainability, or economics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access State of the World 2013 by The Worldwatch Institute in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences biologiques & Développement durable. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Beyond Sustainababble

Robert Engelman

We live today in an age of sustainababble, a cacophonous profusion of uses of the word sustainable to mean anything from environmentally better to cool. The original adjective—meaning capable of being maintained in existence without interruption or diminution—goes back to the ancient Romans. Its use in the environmental field exploded with the 1987 release of Our Common Future, the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Sustainable development, Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland and the other commissioners declared, “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”1

For many years after the release of the Brundtland Commission’s report, environmental analysts debated the value of such complex terms as sustainable, sustainability, and sustainable development. By the turn of the millennium, however, the terms gained a life of their own—with no assurance that this was based on the Commission’s definition. Through increasingly frequent vernacular use, it seemed, the word sustainable became a synonym for the equally vague and unquantifiable adjective green, suggesting some undefined environmental value, as in green growth or green jobs.

Today the term sustainable more typically lends itself to the corporate behavior often called greenwashing. Phrases like sustainable design, sustainable cars, even sustainable underwear litter the media. One airline assures passengers that “the cardboard we use is taken from a sustainable source,” while another informs them that its new in-flight “sustainability effort” saved enough aluminum in 2011 “to build three new airplanes.” Neither use sheds any light on whether the airlines’ overall operations—or commercial aviation itself—can long be sustained on today’s scale.2

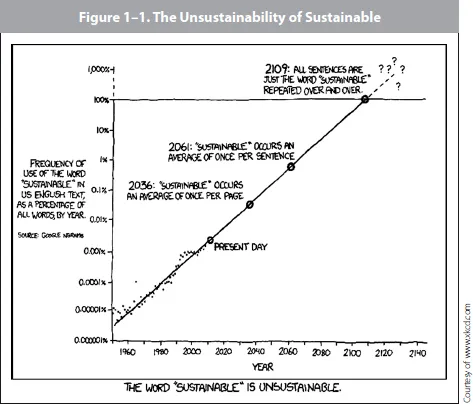

The United Kingdom was said to be aiming for “the first sustainable Olympics” in 2012, perhaps implying an infinitely long future for the quadrennial event no matter what else happens to humanity and the planet. (If environmental impact is indeed the operable standard, the Olympics games in classical Greece or even during the twentieth century were far more sustainable than today’s.) The upward trend line of the use of this increasingly meaningless word led one cartoonist to suggest that in 100 years sustainable will be the only word uttered by anyone speaking American English. (See Figure 1–1.)3

Robert Engelman is president of the Worldwatch Institute.

www.sustainabilitypossible.org

By some metrics this might be considered success. To find sustainable in such common use indicates that a key environmental concept now enjoys general currency in popular culture. But sustainababble has a high cost. Through overuse, the words sustainable and sustainability lose meaning and impact. Worse, frequent and inappropriate use lulls us into dreamy belief that all of us—and everything we do, everything we buy, everything we use—are now able to go on forever, world without end, amen. This is hardly the case.

The question of whether civilization can continue on its current path without undermining prospects for future well-being is at the core of the world’s current environmental predicament. In the wake of failed international environmental and climate summits, when national governments take no actions commensurate with the risk of catastrophic environmental change, are there ways humanity might still alter current behaviors to make them sustainable? Is sustainability still possible? If humanity fails to achieve sustainability, when—and how—will unsustainable trends end? And how will we live through and beyond such endings? Whatever words we use, we need to ask these tough questions. If we fail to do so, we risk self-destruction.

This year’s State of the World aims to expand and deepen discussion of the overused and misunderstood adjective sustainable, which in recent years has morphed from its original meaning into something like “a little better for the environment than the alternative.” Simply doing “better” environmentally will not stop the unraveling of ecological relationships we depend on for food and health. Improving our act will not stabilize the atmosphere. It will not slow the falling of aquifers or the rising of oceans. Nor will it return Arctic ice, among Earth’s most visible natural features from space, to its pre-industrial extent.

In order to alter these trends, vastly larger changes are needed than we have seen so far. It is essential that we take stock, soberly and in scientifically measurable ways, of where we are headed. We desperately need—and are running out of time—to learn how to shift direction toward safety for ourselves, our descendants, and the other species that are our only known companions in the universe. And while we take on these hard tasks, we also need to prepare the social sphere for a future that may well offer hardships and challenges unlike any that human beings have previously experienced. While it is a subset of the biosphere, the social sphere is shaped as well by human capacities with few known limits. We can take at least some hope in that.

Birth of a Concept

Respect for sustainability may go back far in human cultures. North America’s Iroquois expressed concern for the consequences of their decisionmaking down to the seventh generation from their own. A proverb often attributed to Native American indigenous cultures states, “We have not inherited the earth from our fathers, we are borrowing it from our children.” In modern times, the idea of sustainability took root in the writings of naturalist and three-term U.S. Representative George Perkins Marsh in the 1860s and 1870s. Humans were increasingly competing with, and often outcompeting, natural forces in altering the earth itself, Marsh and later writers documented. This is dangerous in the long run, they argued, even if demographically and economically stimulating in the short run.4

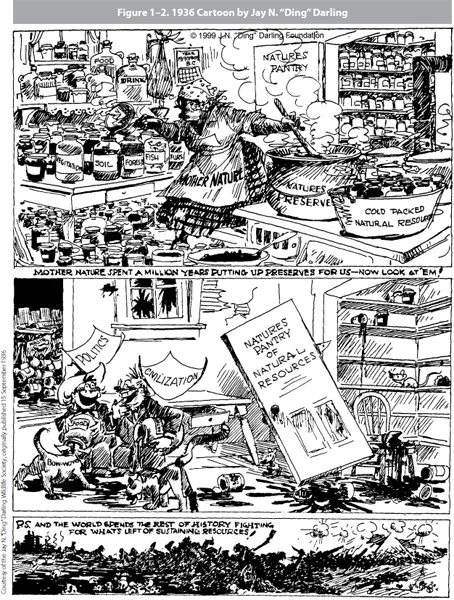

“What we do will affect not only the present but future generations,” President Theodore Roosevelt declared in 1901 in his first Message to Congress, which called for conservation of the nation’s natural resources. The value of conserving natural resources for future use—and the dangers of failing to do so—even made it into political cartoons in the decades that followed. (See Figure 1–2.) The U.S. National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 echoed Roosevelt’s words, affirming that “it is the continuing policy of the Federal Government … to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony, and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans.”5

Two important points emerge from the definition of sustainable development found in Our Common Future, which is still the most commonly cited reference for sustainability and sustainable development. The first is that any environmental trend line can at least in theory be analyzed quantitatively through the lens of its likely impact on the ability of future generations to meet their needs. While we cannot predict the precise impacts of trends and the responses of future humans, this definition offers the basis for metrics of sustainability that can improve with time as knowledge and experience accumulate. The two key questions are, What’s going on? And can it keep going on in this way, on this scale, at this pace, without reducing the likelihood that future generations will live as prosperously and comfortably as ours has? For sustainability to have any meaning, it must be tied to clear and rigorous definitions, metrics, and mileage markers.

The second point is the imperative of development itself. Environmental sustainability and economic development, however, are quite different objectives that need to be understood separately before they are linked. In the Chairman’s Foreword to Our Common Future, Gro Harlem Brundtland defined development as “what we all do in attempting to improve our lot.” It is no slight to either low- or high-income people to note that as 7.1 billion people “do what we all do … to improve our lot,” we push more dangerously into environmentally unsustainable territory. We might imagine optimistically that through reforming the global economy we will find ways to “grow green” enough to meet everyone’s needs without threatening the future. But we will be better served by thinking rigorously about biophysical boundaries, how to keep within them, and how—under these unforgiving realities—we can best ensure that all human beings have fair and equitable access to nourishing food, energy, and other prerequisites of a decent life. It will almost certainly take more cooperation and more sharing than we can imagine in a world currently driven by competition and individual accumulation of wealth.6

What right, we might then ask, do present generations have to improve their lot at the cost of making it harder or even impossible for all future generations to do the same? Philosophically, that’s a fair question—especially from the viewpoint of the future generations—but it is not taken seriously. Perhaps if “improving our lot” could somehow be capped at modest levels of resource consumption, a fairer distribution of wealth for all would allow development that would take nothing away from future generations. That may mean doing without a personal car or living in homes that are unimaginably small by today’s standards or being a bit colder inside during the winter and hotter during the summer. With a large enough human population, however, even modest per capita consumption may be environmentally unsustainable. (See Box 1–1.)7

Gro Brundtland, however, made the practical observation that societies are unlikely to enact policies and programs that favor the future (or nonhuman life) at the expense of people living in the present, especially the poorer among us. Ethically, too, it would be problematic for environmentalists, few of us poor ourselves, to argue that prosperity for those in poverty should take a back seat to protection of the development prospects of future generations. Unless, perhaps, we are willing to take vows of poverty.8

While sustainability advocates may work to enfranchise future generations and other species, we have little choice but to give priority to the needs of human beings alive today while trying to preserve conditions that allow future generations to meet their needs. It is worth recognizing, however, that there is no guarantee that this tension is resolvable and the goal achievable.

If Development Isn’t Sustainable, Is It Development?

The world is large, yet human beings are many, and our use of the planet’s atmosphere, crust, forests, fisheries, waters, and resources is now a force like that of nature. On the other hand, we are a smart and adaptive species, to say the least. Which perhaps helps explain why so many important economic and environmental trends seem headed in conflicting and even opposite directions. Are things looking up or down?

On the development side, the world has already met one of the Millennium Development Goals set for 2015 by the world’s governments in 2000: by 2010 the proportion of people lacking access to safe water was cut in half from 1990 levels. And the last decade has witnessed so dramatic a reduction in global poverty, central to a second development goal, that the London-based Overseas Development Institute urged foreign assistance agencies to redirect their aid strategies over the next 13 years to a dwindling number of the lowest-income nations, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. By some measures, it can be argued that economic prosperity is on the rise and basic needs in most parts of the world are increasingly being met.9

On the environment side, indicators of progress are numerous. They include rising public awareness of problems such as climate change, rainforest loss, and declining biological diversity. Dozens of governments on both sides of the development divide are taking steps to reduce their countries’ greenhouse gas emissions—or at least the growth of those emissions. The use of renewable energy is growing more rapidly than that of fossil fuels (although from a much smaller base). Such trends do not themselves lead directly in any measurable way to true sustainability (fossil fuel use is climbing fast as China and India industrialize, for example), but they may help create conditions for it. One important trend, however, is both measurable and sustainable by strict definition: thanks to a 1987 international treaty, the global use of ozone-depleting substances has declined to the point where the atmosphere’s sun-screening ozone layer is considered likely to repair itself, after sizable human-caused damage, by the end of this century.10

Box 1–1. Toward a Sustainable Number of Us

To link environmental and social sustainability, think population. When we consider what levels of human activity are environmentally sustainable and then, for the sake of equity, calculate an equal allocation of such activity for all, we are forced to ask how many people are in the system.

Suppose for example, we conclude that 4.9 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year and its global-warming equivalent in other greenhouse gases—one tenth of the 49 billion tons emitted in 2010—would be the most that humanity could emit annually to avoid further increases in the atmospheric concentrations of these gases. We then need to divide this number by the 7.1 billion human beings currently alive to derive an “atmosphere-sustainable” per capita emission level. No one responsible for emissions greater than the resulting 690 kilograms annually could claim that his or her lifestyle is atmosphere-sustainable. To do so would be to claim a greater right than others to use the atmosphere as a dump.

One 1998 study used then-current population and emission levels and a somewhat different calculation of global emissions level that would lead to safe atmospheric stability. The conclusion: Botswana’s 1995 per capita emission of 1.54 tons of CO2 (based in this case on commercial energy and cement consumption only) was mathematically climate-sustainable at that time. Although population-based calculations are not always so informative with every resource or system (sustaining biodiversity, for example), similar calculations could work to propose sustainable per capita consumption of water, wood products, fish, and potentially even food.

Once we master such calculations, we begin to understand their implications: As population rises, so does the bar of per capita sustainable behavior. That is, the more of us there are, the less of a share of any fixed resource, such as the atmosphere, is available for each of us to sustainably and equitably transform or consume in a closed system. All else being equal, the smaller the population in any such system, the more likely sustainability can be achieved and the more generous the sustainable consumption level can be for each person. With a large enough population there is no guarantee that even very low levels of equitable per capita greenhouse emissions or resource consumption are environmentally sustainable. If Ecological Footprint calculations are even roughly accurate, humanity is currently consuming the ecological capacity of 1.5 Earths. That suggests that no more than 4.7 billion people could live within the planet’s ecological boundaries without substantially reducing average individual consumption.

Absent catastrophe, sustainable population anything like this size will take many decades to reach through declines in human fertility that r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- About Islans Press

- Other Worldwatch Books

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Worldwatch Institute Board of Directors

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- State of the World: A Year in Review

- 1 Beyond Sustainababble

- The Sustainability Metric

- Getting to True Sustainability

- Open in Case of Emergency

- Notes

- Island Press | Board of Directors