- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Celebrated architect Ralph Knowles, Distinguished Emeritus at USC's School of Architecture, has carefully crafted a book for architects, designers, planners—anyone who yearns to reconnect to the natural world through the built environment. He shows us how to re-examine a shadow, a wall, a window, a landscape, as they respond to the natural cycles of heat, light, wind, and rain. Analyzing methods of sheltering that range from a Berber tent to a Spanish courtyard to the cityscape of contemporary Los Angeles, Ritual House shows us the future: by coining the concept of solar access zoning, he introduces a radical yet increasingly viable solution for tomorrow's mega-cities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ritual House by Ralph Knowles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sheltering

WE HUMAN BEINGS, IN ALL PARTS OF THE WORLD AND in all types of society, seek shelter—a building, a tent, or some other structure that keeps us safe and comfortable. We look for protection from the physical threats of nature and each other, a ceaseless quest that has produced an impressive array of forms. Besides protecting our bodies, we also seek a haven for our souls, our minds, and our spirits. We search for the joys of a home as well as the refuge of a house. In this less tangible regard, the static concept of a shelter gives way to the dynamic concept of sheltering.

As we occupy dwellings, we make certain adjustments for comfort in response to changes in the natural environment. We repeat these adjustments in concert with the unique rhythms of weather and climate in our particular setting. This repetition can give rise to rituals that feed our souls.

These ritual acts of sheltering help explain who we are and where we are in the world. Their development can range from the spiritual to the material, from the hidden to the obvious, from the personal to the communal. Whatever the case, ritual imparts meaning to the ebb and flow of a place.

This book explores the creative potential of such rituals by comparing modes of sheltering from traditional to modern, in places from rural to urban. It then proposes a design paradigm that, by reconnecting our lives to the rhythms of nature, encourages the ritual use of space as a way to conserve energy and to enhance the quality of life.

Making and Keeping

In the modern world we are abandoning traditional ways of sheltering. People everywhere are leaving farms and villages to live in towns and cities, and ancient forms of sheltering are being forgotten. Still, even in a mechanized world, all things must finally respond to nature. Long-established traditions offer a valuable model for today.

When most people depended directly on the land and lived close to nature, their modes of sheltering reflected centuries of learning how to live in a place. Dwellings were well adapted, sited, and shaped in response to local conditions of weather and climate. Corresponding patterns of behavior evolved through generations to match the cycles of time. Spring planting was carried out against a backdrop of fresh green leaves and flowering branches; harvest, against deep colors and bright fruit. Each season was separately ordered like an ancient stringed instrument, a kithara or a lyre, with its own unique resonator. Then cycles repeated as each year brought forth the same rhythmic responses. Rituals belonged to a natural world.

We, in the modern world, identify with growth, making new things in new places. Partly this is the consequence of a universal need to rapidly house people moving from rural to urban settings. Partly it is the result of a swelling global economy that rewards ever-expanding markets over constancy, development over a steady state, and novelty over tradition. The modern background of our lives has a strong sense of linearity and progress, an “arrow of time” replacing traditional cycles. Now, our sheltering rituals seldom mirror the rhythms of nature.

Our predilection for growth raises doubts about a sustainable future. Developers do not pay the utility bills for heating and cooling, lighting and ventilating our buildings. Consequently, designers are encouraged to install energy-intensive systems, “machines for living” that override natural variation. Dwellers who do pay the monthly bills are not always aware of the accumulating costs because they pay in countless small amounts over time, not in a more painful lump sum. Nor do many realize that over one-third of all the energy they consume each year in the United States goes for keeping their buildings comfortable. Over the 50- to 100-year average lifetime of these buildings, the energy price is staggering. In the simplest terms, we “build cheap” and “maintain expensive.”

Additionally, and more to the point of this book, we have lost a challenge to our imaginations. Modern buildings automatically reduce natural variation to a narrow range of light, heat, and humidity without our direct involvement. We have gained uniform standards of comfort, but we have lost the sense of harmony that derives from experiencing the complex rhythms of nature. When we flatten and simplify nature, we lessen the need for many customarily repeated acts that open choices for self-expression.

I don’t mean to suggest that we are somehow ennobled by a wholesale return to more primitive levels of adaptation. There is real suffering in being too hot or too cold, or in having to migrate immense distances to follow the seasons. The permanent places where we spend time do need to reduce stress on our minds and bodies. But there is a real question of means: do our buildings have to hide from us every small variation in the environment that might repeatedly summon us to action?

Rather, something deeply reassuring comes when our actions are consonant with the motions of nature. It is a reaffirmation of our own existence—a continuous call for choices that define who we are as individuals. Our need for this call should not be underestimated nor trivialized by design.

My challenge to designers is to acknowledge and celebrate the rhythmic nature of nature. All things respond to change and to transitions from one state of the environment to another: hot to cold, wet to dry, calm to breezy. Some of these changes are random, as when a passing cloud releases a brief shower, cooling a hot day. Others, though, recur at predictable intervals. We can expect the sun to rise and set, the spring to follow winter, and the rains to come in their season. By working in sympathy with the rhythms of nature, architects and planners can help meet the needs of future generations. They can, as well, cause profound changes in the way people identify with their environments.

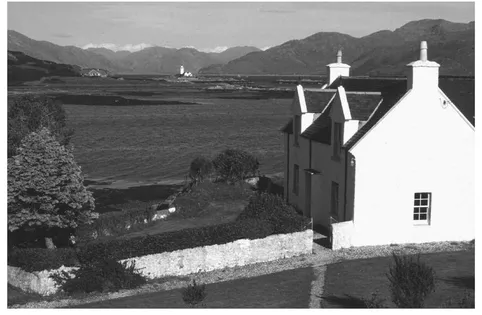

Morning and Evening on the Scottish Isle of Skye.

Rhythm

Cycle and epicycle, the face of the entire world is changed in rhythmic patterns. We may remain still and watch as natural alternations of time transform a landscape. Or we may join directly in the customary actions of people as they go from place to place over hours or seasons. Whether we stand and watch, or move with the ebb and flow, there is an impression of recurring boundaries in space. This is happening all the time and is the thing that really matters.

Landscapes are fixed only momentarily. A passing day on the Scottish Isle of Skye transforms the scene. Early morning mist grays the distant hills and softens the outline of a lighthouse across Loch na Dal. Shrubbery in the foreground blends with the shady face of the house, both revealed only in dark silhouette. Only the roof of the house is highlighted, sketched in by a brighter edge of dormers. A cool breeze ruffles the loch.

In contrast, sunset draws attention to the distant lighthouse across the now dark water. The wind has changed direction and is warmer. The pale clouds of morning are by now grayed in the twilight. Foreground bushes independently catch the light. A small window, almost invisible in the morning, takes over one bright wall of the house. The rock wall shines while the roof recedes in shadow. And seasons will spread over it all.

RHYTHMIC BOUNDARIES IN SPACE

Spatial boundaries in the natural world have their own rhythmic character. For example, in the Owens Valley of California, where a 30-year precipitation cycle has been observed, separate plant communities advance and retreat. Yellow pine advances during wet years while chaparral advances during dry ones. The result is a region of mixing, a “tension zone” between the two plant communities where natural conditions are in constant flux.

Rhythmic boundaries can be seen in nature at all scales. Almost everyone can recall seeing ice crystals in the shadows of a rock. On a winter night tiny spikes appear everywhere. Then in the morning, the sun begins to melt all but those spikes hidden in the rock’s shadow. As the sun moves from east to west, the shadow shifts and, by sunset, only a frosty crescent remains just to the north of the rock. Then it is night and the whole cycle starts over again.

The rhythms of natural boundaries are often complex and contrapuntal. This is evident at the beach where we can see a combination of different rhythms in the rising and falling of the ocean’s surface. Waves act at the fastest tempo chasing birds, children, and barking dogs a few feet up the sand, then tempting them back again. If we stay for most of a day, we can watch the tide ebb and flow, shifting the stage from lower to higher on the beach. If we return on successive days over the course of a month, we will see the effect of a lunar cycle on the life in this tidal zone. And finally, if we return at different seasons of the year, our impressions will swing gradually to and fro as, within the single harmonic texture, each different rhythm retains its separate character.

Just as in nature, rhythmic boundaries also define the spaces we ourselves make and occupy. Most people understand architectural space as enclosed by fixed elements such as floors, ceilings, and walls. Yet space can be thought of dynamically as well, defined by passing sensations of sound, smell, and shadow.

Shadows from a wall alternately expand and contract. And, although we tend to see shadows only as a darker portion of a lighter plane, in fact they have volume, a space we can occupy for a while. How long we might be able to stay within a shadow can depend on the wall’s orientation to the sun. Think of a garden wall in two orientations with a gateway through it.

A wall facing east and west will emphasize a daily rhythm. Morning sun strikes the east side, casting a shadow to the west. As the sun advances, the shadow shrinks, nearly disappearing by noon. Then as afternoon sun strikes the west side, a shadow grows on the east, reversing the picture. Anybody seeking sunshine must move daily from east to west through the gate in the wall. Seeking shade, they ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 - Sheltering

- 2 - Migration

- 3 - Transformation

- 4 - Metabolism

- 5 - Sheltering the Soul

- 6 - Settings and Rituals

- 7 - Boundaries and Choices

- 8 - The Solar Envelope

- 9 - The Interstitium

- 10 - The New Architecture of the Sun

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- ISLAND PRESS BOARD OF DIRECTORS