![]()

1

BEGINNINGS

YOU WILL FORM AN ORGANISATION, THE NAME WILL BE GIFT OF THE GIVERS

‘You feel the calling, you feel the need, you see the suffering of man and you want to do something. There’s a lot of prayer involved. You’ve been shown what the right way is; what to do and what not to do. And things are put very clearly in front of you.’

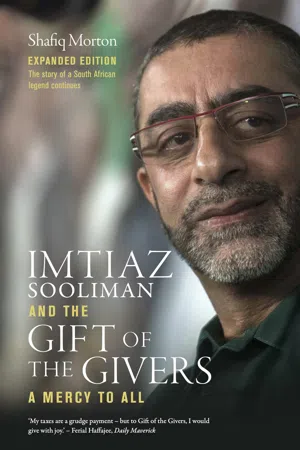

Dr Imtiaz Sooliman

THE SOOLIMANS came to South Africa in the early 1900s from Gujarat, an Indian coastal region bordered by Pakistan. Looking for economic opportunity, patriarch Joosab Gani Sooliman opened a shop in Potchefstroom, a town in the Tlokwe Municipality on the banks of the Mooi River in the North West province.

He was a Memon, a member of an ethnic group originating from lower Sindh in the Indus Delta. History books describe the Memons of Gujarat as the Muslim sailor merchants of India. Today, Memons are renowned for being entrepreneurial, hardworking, innovative, soft-hearted and generous.

Dr Imtiaz Sooliman (who was born in 1962) remembers his father, Ismail, and grandfather, Joosab Gani, always being kind to their customers, discreetly helping destitute families with funeral costs or allowing them to buy basic foodstuffs on tab – even when there was no guarantee of them ever being paid back.

Later, when he went to stay with his mother, Farida, in Durban (his parents separated when he was young) he discovered she was the same. Although she did not have much, he recalls her telling him that you gave charity, even if you could only afford to give one food parcel a month. He remembers walking long distances to deliver his mother’s food to the poor.

Sooliman describes himself as being ‘timid’ as a child, initially fearful of things such as cricket and soccer balls. But he did grow in confidence in Durban, where the streets were a lot tougher and more abrasive than in Potchefstroom.

‘There were many gangsters where my mother lived and they’d stab people in full view. I thought, man, this place is not for me!’

He soon lost his timidity when the neighbourhood children asked him to play soccer with them.

‘So I got a little adventurous. I started out as the reserve. My job was to fetch the ball but by the following year I was the captain.’

Despite his modest circumstances in the shadow of Durban’s leafy Berea, Sooliman matriculated from Greyville’s Sastri College in 1978 and enrolled at the University of Natal’s medical school (now the Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine) to study medicine. He qualified in 1984, completed his internship at King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban and went into private practice in Pietermaritzburg.

He also became an active member of the Islamic Medical Association, an organisation formed in the 1980s by local Muslim doctors to provide medical care to the underprivileged. In 1990 he visited Nacala Hospital in northern Mozambique with the Islamic Medical Association during a severe drought.

‘The difficulty that ordinary Mozambicans experienced in their daily lives touched my heart,’ he said.

‘I went to Mozambique because I wanted to help. I’d never done anything like that before in my life. I saw two frail and malnourished kids in a riverbed digging a half-metre-deep hole and using their tiny hands to scrape out muddy drinking water. That freaked me out. I thought how easily we watered our gardens and turned on taps without thought.’

On his return to South Africa Sooliman bought a fax machine and installed it in his home. He picked out names in the phone book, called mosques and faxed whoever would listen to him, a report of what he’d seen and what needed to be done. Within five days he’d raised R1 million – enough to dig 30 boreholes and provide much-needed relief, including airlifting malaria medication for use by Mozambican authorities.

‘That was my first major humanitarian project. The next year was the Gulf War in Iraq and we got involved there, then the Bangladesh cyclone of 1991.’

It was in the Turkish city of Istanbul that he would enjoy a fateful meeting with a Sufi teacher, Shaikh Safer Efendi, on the urging of his neighbour in Pietermaritzburg. A master in the science of Islamic mysticism, and representing an unbroken chain of Shaikhs going back to the time of Prophet Muhammad, Shaikh Safer would change Sooliman’s life forever.

Sooliman remembers every detail:

‘It was 6 August 1992; I was 30 years old and it was a Thursday in Istanbul. The Shaikh’s manner was so gentle, so soft, so accommodating … his face was engulfed in such light, his deep eyes were filled with such compassion and his presence was so magnetic – you just couldn’t help being drawn to him, falling in love with his personality.’

Sufi masters, regarded as doctors of the human soul, are believed by their followers to possess great insight. Sooliman said there is no doubt in his mind that Shaikh Safer could see his soul.

‘After a congregational religious ceremony the Shaikh just looked at me as if something was talking through him. I do not understand a word of Turkish, but I knew what he was saying. He looked at me and said: “My son I’m not asking you, I’m instructing you. You will form an organisation. The name will be the Gift of the Givers. You will serve all people of all races, of all religions, of all colours, of all classes, of all political affiliations and of any geographical location, and you will serve them unconditionally.”

‘Apart from the unconditionality of service, the Shaikh told me in no uncertain terms that I should never expect anything in return. He told me that the best I could ever expect was a kick up the backside, and if I didn’t get one, I should consider it as a bonus!

‘The Shaikh then instructed me to serve people with kindness, compassion, mercy, and remember that the dignity of man was foremost. No matter what condition there was, I always had to protect the dignity of man; and when I acted, I had to act with excellence.

‘The Shaikh told me that this was an instruction for the rest of my life. The best among people would be those who benefited mankind [a validated axiom of the Prophet Muhammad], and I had to remember that whatever was done would be done through me – and not by me. If I abided by that principle, I would help a lot of people. He warned me not to forget that.’

The other thing that struck the 30-year-old doctor was the make-up of the people gathered around the Shaikh – they were from all walks of life, from all nations, and representing all colours. As a young South African ghettoised by apartheid, Sooliman said this made a marked impression on him. Clearly, all people couldn’t be painted with the same brush.

Sooliman’s brother-in-law, Rafeek Ismail, who was with him at the time, recalls that before their interpreter could translate, the Shaikh would seem to know what was on their minds.

‘It was as if we were speaking through our silence,’ he said.

Gift of the Givers was founded in August 1992, and immediately Sooliman found himself involved in the Bosnian crisis – and remembering the Shaikh’s teaching:

‘Go out in the street without your coat some cold winter’s day, just to see how it is for those who have no coats at all! As long as your stomach is full, you will know nothing about the condition of the starving … satisfy the hungry, so that Paradise may love you.’

Inducted into the Sufi way, Sooliman was encouraged to be humble at all times. As his Shaikh had warned:

‘Become aware of the condition of all those paupers and orphans, for your own wife may become a pauper and your very own children orphans. The wheel of fate turns. None of us knows what is to be …’

His is a job driven by fate. You never know what is waiting around the corner. It’s a question of what he calls a ‘connection’.

‘You feel the calling, you feel the need, you see the suffering of man and you want to do something. There’s a lot of prayer involved. You’ve been shown what the right way is; what to do and what not to do. And things are put very clearly in front of you.’

Sooliman believes that it’s the conditions of others less fortunate than him that keeps him going. You want to help over and over when you see the pain and suffering of others. The most satisfying thing is the smile on a person’s face when they are lifted up.

To ensure that Gift of the Givers runs effectively as an NGO, Sooliman insists on quality and professionalism at every turn. The organisation is primarily funded by ordinary South Africans, people who make great sacrifices to give him money, and also corporates whose ethos demands delivery.

There are no short cuts. He runs a core staff of about 50 people in Pietermaritzburg, Durban, Johannesburg and Cape Town in South Africa, and Mogadishu (Somalia), Blantyre (Malawi), Darkoush (Syria) and Sana’a (Yemen). Volunteer doctors, paramedics and search-and-rescue teams are on standby. Sooliman and his team always render humanitarian assistance themselves, and while happy to partner in projects, Gift of the Givers hardly ever works through third parties or agencies at the point of delivery.

He learnt very quickly that to be effective in the emotionally demanding field of humanitarian work he had to have a clear mind and a cool temperament.

‘It is impossible not to feel for people, but you have to be ice-cold in this type of situation … you really cannot afford to sit down and cry. You may end up doing nothing. I consider myself to be a very gentle person, but I can be icy cold at the same time. I feel for people, but I have never got emotionally attached.’

Another lesson was that because of the urgency of a situation, you had to be straightforward. Sooliman’s blunt, off-the-record exchanges with officials are legend but – as he says – they have at all times been driven by a concern for helping others, rather than scoring points and satisfying the ego.

‘I call a spade a spade. I’ve found that in the type of work we do, it’s the only way we can really survive and help others to survive.’

Sooliman maintains that he learnt almost everything about humanitarian work in Bosnia. There, every possible obstacle was put in front of him, every possible bureaucratic hurdle was erected, and at every turn his patience was tested.

‘Each challenge makes you stronger,’ is his understated response to what was a highly taxing and troublesome time in his life.

The Bosnian conflict occurred in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia that had fractured along sectarian lines after the death in 1980 of its leader, Josep Broz Tito. Yugoslavia had consisted of Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Macedonia.

An astute man who took power in 1945, Tito’s internal policy of crushing sectarian nationalist sentiment and enforcing unity between the six Yugoslav nations, saw him remaining in power until his death 35 years later.

Yugoslavia consisted of three major ethnic groups: the Catholic Croats, the Orthodox Serbs and the Bosnian Muslims. Tito had known better than most the real substance of Yugoslav nationalism, and it had taken his iron fist to keep its destructive forces at bay. However, after his death the socialist federation had started to crumble, and with the implosion of the Soviet Union, the uneasy framework of Yugoslav state unity had collapsed. Competing nationalist movements rose to the fore after the 1990 elections.

When Slovenia and Croatia declared independence in 1991, the Yugoslav armed forces – by now the blunt instrument of Serbian nationalism – prepared to ...