- 652 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This vintage book contains a complete guide to playing polo, with information on rules, strategy, training ponies, equipment, history, notable clubs, development, and more. This volume is highly recommended for those with an interest in the history of the game, and it is not to be missed by collectors of vintage sporting literature. Contents include: "Ancient Polo", "The Hurlington Club and its Influence on Polo", "The Ranlagh Club and the Expansion of Polo", "The Growth of Polo in London and the Provinces", "Regimental Polo", "The Training of the Pony", "Elementary Polo", "Tournament Polo and Team-Play", "Umpires and Referees", et cetera. Many vintage books such as this are becoming increasingly scarce and expensive. We are republishing this volume now in an affordable, modern edition complete with a specially commissioned new introduction on horses used for sport and utility.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781473340053Subtopic

Sport & Exercise Science

CHAPTER I

ANCIENT POLO

POLO is perhaps the most ancient of games. When history was still legend we find polo flourishing. All our best games are derived from it, and cricket, golf, hockey, and the national Irish game of hurling are all descendants of polo. The historic order was reversed when in England polo on its first introduction was called “hockey on horseback,” and in Ireland “hurling on horseback.” In reality these games are polo on foot.

The cradle of polo was Persia, and from that country the game spread all over the East, taking root most firmly in India, and at Constantinople under the Byzantine Emperors.

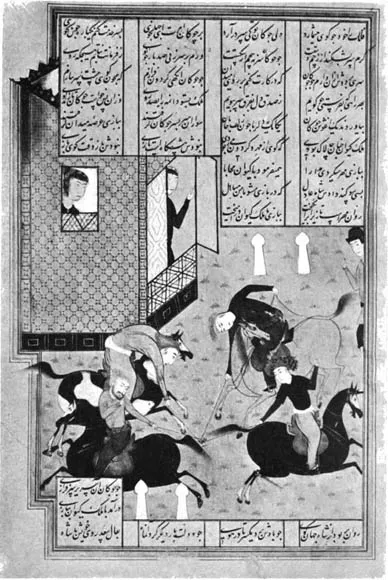

It is very difficult to separate legend and history in the stories of Oriental lands—so much of the history is legendary, so many of the legends are historical. But, however we may puzzle over the succession and even the identity of the kings of the various dynasties, of one thing we may be absolutely sure, that from the earliest times to the eighteenth century there was always polo at the Persian court. Every Persian king either took part in the game or looked on while his courtiers played.

I have examined the various authorities in order to see if it was possible to reconstruct the old Persian polo from their writings. I felt that this would be more interesting than the mere record of the references to the game in the pages of poets and historians. So I have endeavoured to discover what their methods of play were, in the old days, what rules they played under, and in what ways the game varied or developed during successive periods and in different countries.

Persian polo differed from the game in other countries by the fact that it was a national sport. In the poetical histories or historical poems in which Persian literature is so rich, the heroes are often celebrated for their skill at polo. Nor are their victories in war or love described in language more high flown. This shows the esteem in which the game was held. The Persians were a nation of horsemen, and every Persian youth of rank was taught not merely to ride, but to be at home in the saddle. It has more than once occurred to me, while writing this chapter, as strange that polo, which must have been well known to the peoples that came in contact with the Persians—the Greeks, the Romans, and the English,—should never have made its way into their countries. The reason in all probability was the inferiority of the horsemanship1 of the Greeks and Romans, and the lack of suitable horses. The Persians on the other hand had in their horses light, active, well-bred animals of Arab type, and about 14.2 in height.

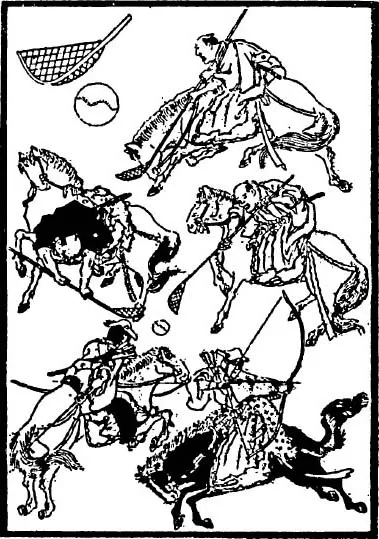

It seems likely that while the natural gift for, and acquired skill in horsemanship must have encouraged polo, this game improved the riding of the Persians and increased the efficiency of their cavalry. There is no such school of horsemanship as polo, especially for acquiring the strong, easy, confident seat that is desired for modern cavalry, according to the latest official instructions on their training. We speak, however, of polo generally, but there have been no less than five, or, including our modern game, six varieties of polo during its existence of at least 2000 years. Some of the variations in the game are considerable. For example, there was the Indian form known as rôl, which consisted in dribbling the ball along the ground, and the interest of which lay in keeping possession of it by means of dexterous turns and twists of a long stick; and the Byzantine form of the game, which I do not know better how to describe than by saying that it was a kind of la crosse on horseback. Of both these I shall have occasion to write later on.

In ancient polo there are only three constant things, the horse, the ball, and an instrument to strike the latter with. Everything else varied, the number of players, the size of the ground, the height of the horses, the shape of the stick, and even the material of which the ball was made. This last has, at all events since the game made its way to the borders of Thibet, been known as polo from a Thibetan word signifying willow root, from which material our English polo balls are still turned. All polo balls were made of wood, except that in the twelfth century the ball used in Byzantine polo was either made of, or covered with leather.

The horse ridden was, I think, most commonly the ordinary Arab of about 14.2; but some ancient pictures show that two kinds of ponies were sometimes used—first the larger Arab, and secondly a small, active, somewhat coarse pony, which was probably a hill pony. It is of course quite possible that, like the modern pony breeder, the old Persian appreciated the value for polo of a cross of true pony blood. But, however that may be, the pictures are only evidence of the stamp of ponies used in the artist’s own time.

The polo stick has varied very much, and as in our day there is no standard for the length of the stick, the shape of the head, or the angle at which the latter is fixed to the head, but each player uses the kind that suits him best, so in ancient times the shape and length of the stick varied greatly. The earliest form of which we know anything had a kind of spoon-shaped head, and this was probably not used, as one or two writers have suggested, for carrying the ball, but for those lofty strokes which, as we see from the account in the Sháh-náma, were much admired.

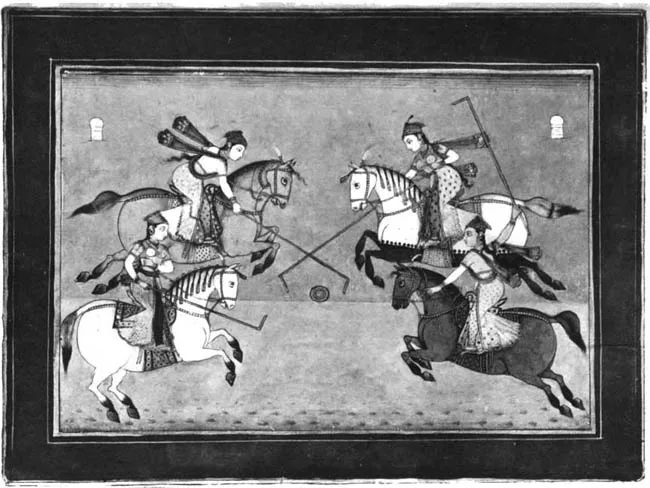

THE LADIES’ STAND.

THE TWO MEN IN FOREGROUND ARE MAKING NEAR SIDE STROKES.

THE TWO MEN IN FOREGROUND ARE MAKING NEAR SIDE STROKES.

STICK CROOKING IN ANCIENT POLO.

This shape of stick was a survival of a still earlier form of polo than has come down to us in the old pictures. I think it seems likely that the earliest game was simply a trial of skill with the stick and ball, that there were no limits to the ground nor were there any goals. The players simply tried to outdo each other in fancy strokes, such as hitting the ball into the air, striking or volleying it while flying. The struggle was for the possession of the ball, and those were adjudged the victors who showed most skill and address in the use of the stick and the management of their horses. The division into sides, the establishment of rules, and the erection of goals were later developments. The more orderly game soon modified the stick, which became first a hockey stick and then a hammer-headed mallet such as we have now. I imagine that the two forms of polo, the orderly game, and the exercise of skill in horsemanship and in the use of the stick, existed side by side for some time, and that we have accounts of both. In the earlier stage of the game a ball or balls were flung down and an unlimited number of young men exhibited their skill before the king and his court. In the later phase sides were chosen, rules observed, and the game was played much as we play it now.

There were also three ways of starting the game; the first and most ancient, which came from the primitive polo, is that retained in Manipur and Gilgit to this day. The chief man among the players gallops down carrying the ball till he reaches the middle of the ground, when he throws it up into the air and hits it flying. “A hit should be made from the centre of the ground, and a good man will often hit a goal. The starter on his side must be able to pick up the ball for the goal to count. The man who has hit the goal will throw himself off his pony and try to pick up the ball while the other side with fine impartiality hit him or the ball or ride over him in their endeavour to save the goal.”1 In this sentence I fancy I find another survival of ancient polo, and that we have here one of the oldest rules of the game. If this was so it may be almost a source of wonder that polo never found its way into the Roman amphitheatre. A game by professionals with rules like this might have been exciting enough and sufficiently dangerous to make a Roman holiday. The ball was also from a very early time bowled in, much as our umpires do now, between the players drawn up in two ranks. The third way was to place the ball in the centre of the ground. The two sides were then drawn up, each on its respective back line, started at a signal and raced for the possession of the ball.

The grounds varied in size, but their surfaces were as carefully looked after as they are now. The Persian polo ground was sometimes twice as long as ours but seldom more than 170 yards in breadth. This shows us that polo must have been a fast-galloping game. On the other hand, the strokes used were much the same as ours, and players were particularly fond of the stroke under the pony’s neck to the left front of the player. Long shots at the goal were then, as now, often attempted by the best players. The fixed goals show that they used an established ground. The posts were of stone, and, if we may judge by the old pictures, solidly and firmly built. This must have been dangerous, for we know that even the wooden posts used before the paper ones were introduced caused several accidents. On the other hand, we must remember that the Persians were extraordinarily skilful and practised horsemen of the Oriental type, that their ponies were of Eastern breeds accustomed to stop and to wheel on their haunches, and were strongly bitted. No Oriental ever lets his horse out of his hand. His horse’s hind legs are always well under him, and the Arab horse is from hereditary habit the handiest of animals, as those who have ridden him after a jinking hog know well. Thus the danger was less than it would be with English ponies. These permanent goal-posts were twenty-four feet apart, giving the same length of goal line as we have to-day. In the best ancient polo, as in our first-class matches in modern times, there were four players on each side. Combination and team-play were undoubtedly understood, as I shall presently show, and there were some very clearly defined rules.

It was certainly forbidden to stand over the ball, and perhaps to slacken speed before you hit it, but at all events it was considered bad form not to gallop. It was also thought to be bad play to hang about outside the game for the chance of a run, and I think that about the tenth century there was a rule which forbade offside. When I write of rules I do not of course know if there was a written code, but it is certain there was a traditional form of rules and etiquette handed down and strictly adhered to.

Polo was taken very seriously in Persia and India. Skill and address at the game were recommendations to promotion at court. It was thought that polo was a game that showed the character of the player and tested his temper, courage, and disposition. The Emperor Akbar watched his young nobles and soldiers at the game, and formed his conclusions as to their fitness for service from their demeanour. Certainly we have reason to think after the experience of our last war in South Africa that such a method of selection would not work badly.

Now let us turn to the authorities on which these conclusions as to ancient polo are based. It is one of the facts which show us how deeply polo was rooted as a national sport in the affections of the Persians, that allusions to it are so frequent in their poets. The Persians loved and indeed still love poetry greatly, and therefore polo must have been thoroughly known and understood, since it is so often used in the metaphors of the poets, and references to the game are continual. Indeed, one mystic poem is called “Stick and Ball.” It would occupy too much space to compile an anthology of polo from the Persian poets. But we may note some of the more remarkable passages on which I have based my reconstruction of ancient polo. And perhaps I cannot begin better than by a translation and commentary on the account of the first recorded international polo match. This is taken from the Sháh-náma, the Iliad of Persia. This match was played perhaps at Tashkend between the Iranians and the Turanians. It is interesting to note that the inhabitants of the two countries, though constantly at war, are supposed by the poet to be equally well acquainted with the game, and to have had a common code of rules. The occasion of the match was as follows:—Siawusch, a Persian prince, had taken refuge at the court of Afrāsiāb, king of the Turks, having fallen into disgrace at his father’s court, a woman being, as usual in the East, at the bottom of the mischief. Even though Siawusch had proved his innocence by passing through the ordeal of fire, yet the lady’s word was taken against his, and the young prince went into exile.

With some faithful companions he took refuge at the court of Afrāsiāb, the hereditary foe of his race and family, and was by him well received and treated. Were they not both keen polo players? No doubt Afrāsiāb saw in the arrival of the Persians the prospect of an unusually interesting match. The king gave them a week to rest the ponies in, and then one night after dinner he proposed to Siawusch a polo match in the morning. “I have always heard,” he added, “what a great player you are, and that when you hit the ball no one else has a chance.” To which Siawusch replies that he is quite sure that in polo as in everything else the king is his superior, and then follows half a page of an exchange of elaborate compliments. Neither, however, as will be seen, meant to throw away a chance of winning. In the morning the players were early on the ground in the highest spirits, galloping their ponies and knocking the ball about. Then the king proposed to Siawusch a “pick up” game, each to choose six men from Afrāsiāb’s followers. Siawusch was too good a courtier to permit this, and he begs the king to allow him to play on the same side as his majesty. “If, indeed you think me good enough,” says the prince with a modest politeness. But the king, resolved not to be done out of his game, hints that he is determined to have a match, reminds the prince that his reputation as a player is at stake, and urges that on his side he wants to test his visitor’s skill. On this Siawusch yields and the king arranges the sides, picking out the best players for himself, especially Nestiken, “wonderfully keen at riding off,” and Human, “noted for his control of the ball.” To Siawusch he only gave the hard riders, and the prince was not disposed to acquiesce. He objects that this will never do, and that the king’s own men will not support a stranger: “I shall be left to hit the ball alone.” Then comes a passage from which I infer two things—first, that polo had in those early days a code of rules common to the different countries in Asia in which it was played; secondly, that “team” play or combination was appreciated and practised. For Siawusch was anxious to have his own team, and begged to be allowed to bring on to the ground his Persian followers, “who will play in combination with me according to the rules of international polo.” I am not quite sure that the king was pleased—“he listened and agreed,” is the curt remark of the poet, and this is in contrast to the flow of compliments that had taken place when King Afrāsiāb thought he was going to have things his own way. Siawusch then picks six first-class players. They played apparently seven a-side.

“Then the band began to play, and the air was filled with dust,” which will recall familiar experiences to Anglo-Indian players. “You would have thought there was an earthquake, so great was the noise of trumpets and cymbals.” This is quite the Oriental idea of a band.

The king started the game by bowling in the ball, which we are told he did “in the correct manner,” here again giving a trace of a rule. Siawusch was quick on it and before it had touched the ground skied the ball in true Oriental style, hitting so hard that it was lost. Then the mighty king ordered another ball to be brought to Siawusch (new ball, umpire!). The prince took it, kissed it (the band began to play cymbals and drums da capo), Siawusch changed p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Polo - Hints to a Beginner

- Horses–Sports and Utility

- Preface

- Contents

- 1. Ancient Polo

- 2. The Hurlingham Club and its Influence on Polo

- 3. The Ranelagh Club and the Expansion of Polo

- 4. The Growth of Polo in London and the Provinces

- 5. Regimental Polo

- 6. The Training of the Pony

- 7. Elementary Polo

- 8. Tournament Polo and Team-Play

- 9. Umpires and Referees

- 10. The Pony and Stable Management

- 11. Polo Pony Breeding

- 12. The Polo Club: Its Appliances and Expenses

- 13. Recollections of Twenty Years

- 14. Thoughts and Suggestions on Handicapping

- 15. Polo in Australia

- 16. Polo in America

- 17. The Rules of Polo in England

- 18. Rules of the Indian Polo Association

- Appendix

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Polo by T. F. Dale in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.