1

The Mortification of Harvey Leach

Humour and Horror in Nineteenth-Century Theatre of Disability

Michael Mark Chemers

THE MACABRE, AS A GENRE, is characterised not only by the presence of horror, but also of humour. Indeed, these two aesthetic states are often seen together in many genres, even as far back as the Greeks. In scholarly essays linking horror and humour, there is a recognition of a certain sympathy between the two. However, because of the revulsion of horror and the pleasure of humour, most theorists consider them to be diametrically opposed – two irreconcilable points of one of the binaries upon which Western thought stubbornly depends. But as is the case with most binaries, a careful examination reveals that these putatively oppositional poles are, in actuality, deeply imbricated. Using Noël Carroll’s 1999 essay ‘Horror and Humor’ as a jumping-off point, I examine this overlap closely in a particular event that occurred during a nineteenth-century exhibition: the exposure and humiliation of an actor with a disability by the name of Harvey Leach.

It is not the purpose of this chapter to create a general theory of humour and horror. Indeed, this essay will demonstrate that the experience of horror and humour are processes (or, more often, the same process) which operate within dynamic systems of representation, shaping them in strange ways. As I have elsewhere demonstrated, it is more productive for the historian to recover specific case studies and apply those analytical methods that are most productive of useful enquiry.1 Rather than general-ise, this essay looks forensically into a single instant in 1846 that demonstrates the deeply systemic intersection of humour and horror.

The Mortification of Harvey Leach

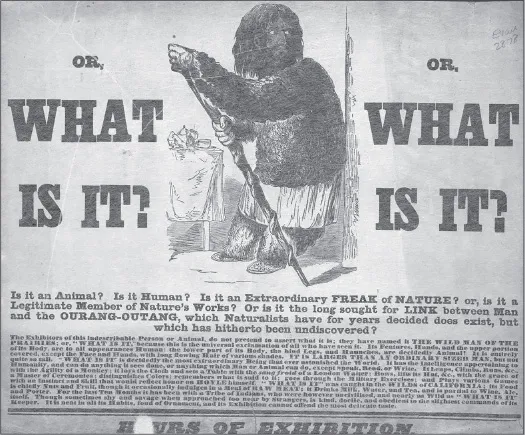

On 29 August 1846, curiosity seekers attended a live human exhibit at London’s Egyptian Hall of ‘The Wild Man of the Prairies, or What Is It?’. They had been lured by a lurid image in The Times featuring a handsome-faced man with dark skin, long dirty hair and a hairy body proportioned as a strong man from the torso up but possessed of relatively short legs (see figure 1). The man is leaning against a wall, supported by a carved staff, looking around with intelligence and curiosity. His modesty is maintained by a pair of shorts. Behind him, incongruously, is a table set with a tea service. The text of the advertisement reads, in part:

The exhibitors of this indescribable person or animal, do not pretend to assert what it is; they have named it THE WILD MAN OF THE PRAIRIES; or, ‘WHAT IS IT,’ because this is the universal exclamation of all who have seen it … ‘WHAT IS IT’ is decidedly the most extraordinary being that ever astonished the world.

When the exhibit opened, the creature, supposedly caught in California, was discovered in a cage, covered in thick hair, snarling, leaping and gnawing on raw meat. The audience must have been astonished – then, half an hour into the exhibition, one of the visitors suddenly recognised the What Is It? to be renowned American actor and aerialist Harvey Leach. The visitor opened the cage, entered it, and shook the creature’s hand, saying something in the order of ‘how are you, old fellow?’. Indeed, the wild man was Leach – the producers shut down the exhibition and the spectators got their money back. His reputation in tatters, Harvey Leach died some eight months later.

What to make of this occurrence, unusual even in the strange and convoluted history of disability and popular performance culture in the nineteenth century? Harvey Leach’s career ran the gamut of the many kinds of performance that we would today call ‘freak shows’, which ranged from legitimate big-ticket performances featuring people with disabilities to these ‘human exhibitions’. The student of such events must tread carefully, for the freak show of the nineteenth century was a cultural organism that fed mainly on lies – lies told usually to enhance and, paradoxically, relieve fear of the extraordinary body by exaggerating its apperception as inhuman, for purely mercenary reasons. But freak shows, and the exposure of Leach at the Egyptian Hall, are also exemplary of the aesthetic proximity of horror and humour. Investigating the mortification of Harvey Leach renders legible a strange phenomenon: that the mechanism by which audiences identify and process humour and horror are far more closely aligned than we might have previously supposed.

Figure 1. This image of Leach as Alnain the Gnome King is in the London Metropolitan Archives (Collage record no. 323406, Cat. SC_ GL_ENT_018a), is mistitled as ‘“What Is It” attraction at the Egyptian Hall, appearing to be half human half animal’ and is misdated.

Who was Harvey Leach?

Born, according to what evidence exists, in Westchester County, New York, in 1804, Leach enjoyed a celebrated career as an aerialist, equestrian and acrobat. Sometimes erroneously described as ‘the legless dwarf’, Leach’s ability to draw crowds seemed drawn from his feats of physical strength, performed entirely with his hands and arms, his facility as a clown and his conventional good looks.

On 31 January 1838, Leach began his most celebrated performance at London’s Adelphi Theatre as the title character in a play called The Gnome Fly (see Figure 2). Leach, under his performing name ‘Signor Hervio Nano’, authored the play, which is described as an ‘extravaganza’ involving Alnain, the ‘King of the Gnomes and Dives’. Directed by the Adelphi’s manager Frederick H. Yates, the fairy-tale melodrama served as a vehicle for Leach’s greatest feats as an acrobat and actor, as he also appeared as Sapajou, Baboon to the Prince of Tartary and as a magical bluebottle fly.

The reviewers of The Times, often sardonic when discussing exhibitions of extraordinary bodies, were amazed by Leach’s acrobatics as the Gnome Fly. One review of opening night reads:

He climbs … along the side of the theatre, gets into the upper circle in a moment, catches hold of the projection of the ornaments of the ceiling of the theatre, crosses to the opposite side, and descends along the vertical boarding of the proscenium … In a word, [he] performs some of the most astonishing feats ever exhibited within the walls of a theatre.2

Figure 2. Advertisement from The Times, 29 August 1846.

The Gnome Fly ran for forty-six performances between 31 January and 7 April 1838. Between The Gnome Fly and a companion piece, The Major and the Monkey (a burletta by Joseph S. Coyne starring the prominent character actor O. Smith, in which Leach played the ‘Monkey’), Leach appeared at the Adelphi fifty-four times in the 1837–8 season.3

Leach had even better luck in the United States. The Gnome Fly enjoyed a wildly successful run at New York’s Bowery and Chatham Theatres from 1840–1, which Leach supplemented by playing ‘Jocko, the Brazilian Ape’ at the Chatham and appearing in circuses as an equestrian and clown.4 P. T. Barnum recorded a meeting with Leach in 1844 in his first autobiography, published in 1855:

I was called upon by ‘Hervio Nano’, who was known to the public as the ‘gnome fly’, and was also celebrated for his representations as a monkey. His malformation caused him to appear much like that animal when properly dressed. He wished me to exhibit him in London, but having my hands already full, I declined … The exhibition opened Egyptian Hall, and as a matter of curiosity I attended the opening. Before half an hour had elapsed, one of the visitors, who knew ‘Hervio Nano’, recognized him through his disguise and exposed the imposition. The money was refunded to visitors, and that was the first and last appearance of ‘What is it?’ in that character. He soon afterward died in London.5

But this recollection seems at odds with a letter that Barnum wrote to his friend and fellow entrepreneur Moses Kimball in August 1846:

The animal that I spoke to you & Hale about comes out at Egyptian Hall, London, next Monday, and I half fear that I will not only be exposed, but that I shall be found out in the matter. However, I go it, live or die. The thing is not to be called anything by his exhibitor. We know not & therefore do not assert whether it is human or animal. We leave all that to the sagacious public to decide.6

This letter seems to give the lie to Barnum’s 1855 reconstruction of events; he was involved in this exhibition and had a significant hand in designing the ballyhoo of the event to avoid accusations of fraud (this is a characteristic of Barnum’s promotional genius). That Barnum had a proprietary interest in the role of What Is It? is evinced by his resurrection of the character with the more famous William Henry Johnson, or ‘Zip’, around 1865.7

The exposure of Leach as a fraud was of great interest in the press throughout the following week:

A correspondent of the Times – who characteristically signs himself ‘Open-eye’ – paid his shilling and was shown into the sanctum of the monster. He at once discovered the ‘Wild Man of the Prairies’ to be no other than the exceedingly tame dwarf Hervio Nano, otherwise Harvey Leach, who about ten years since performed the part of a blue-bottle at the Adelphi, Surrey, and other minor theatres.8

The identity of the man who exposed and mortified Leach may also be discernible from the historical record. In Shows of London, Richard Altick reports that the offending party was one Mr Carter, a lion tamer and possibly a rival of Leach, who held a grudge against Barnum for not allowing Tom Thumb to ride General Washington, a mammoth horse that belonged to Carter, during Carter’s benefit night in the previous season at the Egyptian Hall.9 Altick reports that, oblivious to protestations from the What Is It?’s keepers, he entered the cage:

Then, grabbing its forepaw, he ‘drew the unresisting creature to the centre of the cage – with one strong tug tore the shaggy skin all down its back and sides’ – and out, sheepishly no doubt, stepped the Gnome Fly. Carter’s punchline was said to have been: ‘And now, as you’ve been living on raw meat so long, come down to Craven street and have a broiled steak with me’.10

Even Altick allows that this account may have been ‘apocryphal’, but the next day, a letter signed ‘Open-eye’ did in fact appear in The Times, which read in part:

Being a bit of a naturalist, and consequently anxious to see the ‘what is it’ at the Egyptian-hall in its first wildness, I arose two hours earlier than usual, proceeded thither in a kind of feverish excitement, paid my shilling magnanimously, and was shown into the sanctum of the ‘wild man of the prairies’ … Oh, the ghost of Buffon! What was my surprise when, at the first glance, I found ‘what is it’ to be an old acquaintance – Hervio Nano, alias Hervey Leech, himself! … I will tell you how the ‘wild man’ … went to his kennel to argue with the proprietor on the propriety of returning my shilling.11

If Altick is right, it seems likely that Carter was allied with, or was indeed, ‘Open-eye’, and engineered the entire exposure by way of revenging himself on Barnum.

The death of Harvey Leach occurred in May 1847, eight months after the exposure of the What Is It?. James W. Cook, Jr, writing in 1996, finds an eyewitness account of Leach, his walking-on-the-ceiling trick, and his death in Henry Mayhew’s 1851 London Labour and the London Poor. ‘The Strong Man’ relates:

That ‘What is It’, at the Egyptian Hall killed him. They’d have made a heap of money at it if it hadn’t been discovered. He was in a cage, and wonderfully got up. He looked awful. A friend of his comes in, and goes up to the cage, and says, ‘How are you, old fellow?’ The thing was blown up in a minute. The place was in an uproar. It killed Harvey Leach, for he took it to heart and died.12

It is impossible to know whether Leach died of embarrassment over this event, as the side-show strongman suggested. His mortification, however, emphasises the strange unification of horror and humour, and an analysis of this moment is revelatory of the deep imbrication of these aesthetic conditions.

Humour and Horror

Noël Carroll addresses this complex imbrication in his 1999 essay ‘Horror and Humor’. Carroll begins by noting the apparent antagonism between the states. ‘At least at first glance’, he writes, ‘horror and humor seem like opposite mental states. Being horrified seems as though it should preclude amusement. And what causes us to laugh does not appear as though it should also be capable of making us scream.’13 But Carroll goes on to question a particular case, that of two portrayals of Frank-enstein’s monster (by the actor Glenn Strange) doing the same schtick in two films: House of Frankenstein (1944) and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). In the first, the portrayal is met with horror, and in the second, humour.

What to make of this, especially in light of a trend among modernist cultural critics to associate the humour and horror reactions with similar stimuli? Carroll notes that in Freud’s famous and influential 1919 essay ‘The Uncanny’, the feeling of uncanny horror is born when the percipient is unsure whether the subject of their gaze is living or mechanical, while Henri Bergson in his 1901 essay ‘Laughter’ considered that humour is triggered by exactly the same stimuli. Carroll posits a third position from which the comic and the horrific can be viewed as springing from similar inputs, which then begs the question of what exactly the difference is between these aesthetic responses.

Monsters are common if not completely indispensable elements of horror. Carroll defines monsters as creatures whose existence confounds widely held views of what is physically possible, inviting speculation into the inexp...