![]()

1

Introduction

The Inner Hebridean island of Islay is well known for its Gaelic heritage. In recent years, this has been clearly visible from the islanders’ large-scale participation in local and national mòd gatherings, the great strides being taken locally in Gaelic medium education, and the unusually high concentration of Islay whisky distilleries, whose distinctive take on the Gaelic tradition of uisge beatha, the water of life, has ensured a brand familiarity with the island and its Celtic roots throughout the world. There are equally compelling reasons to believe that these roots run deep. In 1791, for example, the Reverend John McLeish, minister of Kilchoman parish, remarked in his report for Sir John Sinclair’s Statistical Account of Scotland 1791–1799 that ‘[t]he Gaelic is the general language of the common people’.1 For much of the 16th and 17th centuries, and almost universally before the forfeiture of the Lordship of the Isles by James IV in 1493, there is an abundance of evidence to show that Gaelic was also the language of the nobility and the landed gentry.

There can be little doubt that the high status enjoyed by the Gaelic language and culture in Islay towards the end of the Middle Ages was secured by the arrival of the Argyll-based sea king Somerled MacGillebride and his sons around 1150.2 Within a century, their dynasty was so firmly established that Somerled’s great-grandson, Angus Mòr MacDonald, had the moniker ‘de Ile’, ‘of Islay’, confidently incorporated into his personal seal.3 Angus’ own descendants of the 14th and 15th centuries came to hold sway over a vast transmarine territory, which they controlled through a network of strongholds in the Hebrides, the north west mainland of Scotland and Ireland.4 It is poignant to note, however, that these MacDonald Lords of the Isles continued to favour Islay as a base of operations, holding court at their proto-urban castle complex on Eilean Mòr in Loch Finlaggan,5 issuing Acts and edicts including the unique Gaelic language charter of 1408,6 and even more significantly, designating the adjacent islet as the official assembly place for the Council of the Isles. By the time Dean Monro wrote his Description of the Occidental i.e. Western Isles of Scotland in the 16th century, this was known as the ‘Counsell Ile’, or Eilean na Comhairle in Gaelic.7

While the MacDonalds’ relationship with Islay has become heavily romanticised in the years since their demise, it was born from a practical appreciation of the island’s strategic importance. The main attraction was almost certainly its location. Islay sits at the gateway to the Irish Sea (Figure 1.1), providing a safe haven between the treacherous waters of the Coire Bhreacain and the North Channel, and commanding the main thoroughfare between the west coast of Scotland and Ireland. But control of the island brought other advantages. Although Islay itself is relatively small, at around 62,000 hectares, its assorted landforms boast a range of ecological zones and a wealth of natural resources, including large tracts of unusually productive farmland, based on limestonederived soils and shell sand machair,8 capable not only of supplying the extravagant household needs of resident nobles, but also of billeting a standing force of several hundred dedicated fighting men.9 The adjacent Sound of Islay was another major asset. This narrow stretch of water separating Islay from the island of Jura is of obvious importance as a maritime highway, but it could also be brought into service as an extended natural harbour to assemble the Lordship fleets of longships, birlinns and highland galleys, reported on occasion to have numbered in their hundreds.10

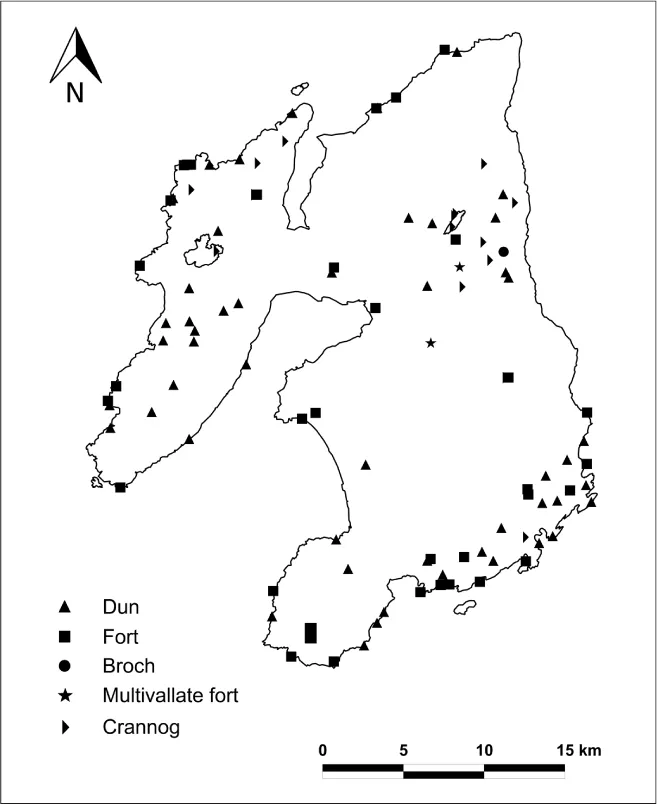

In short, Islay was a valuable prize. By the Early Modern era, its unique combination of strategic importance and agricultural productivity were enshrined in the byname ‘Banrìgh nan Eilean’ or queen of the Hebrides.11 With this being the case, it seems unlikely that Somerled and his brood would have been the first to covet its gifts. On the contrary, it can be inferred from the large number of ruined fortifications still dominating the Islay landscape that the struggle for control of local resources is one that echoes far back into antiquity. Indeed, it is a struggle that seems to intensify the further back it is traced. The scattering of crumbling castles and fortified dwellings from Islay’s medieval period is eclipsed by the dozens of drystone duns, forts, brochs and the island dwellings known as crannogs which have survived from its Early Christian era and Iron Age (Figure 1.2).12 Reliable written accounts for this earlier period are scarce. However, between the snippets of Hebridean reportage recorded in the Irish annals and the more localised anecdotes preserved in Adomnán of Iona’s late 7th-century Vita Columbae, there is enough to suggest strong cultural connections between the native Ilich (people of Islay) and their better documented neighbours in Ireland. In the society described by the early Irish law codes on status Críth Gablach (Branched Purchase) and Uraicecht Becc (Little Primer), land ownership appears to have been a key component in social standing. In theory, every freeman was either a flaith, ‘lord’, or céle, ‘client’. Social rank was qualified by property, and those who were imprudent enough to lose their lands were stigmatised through loss of status.13 As a result, every part of the landscape, whether physically occupied or not, was legally owned and jealously guarded. There is no reason to believe that Islay was any different. In fact, this assumption finds support in the originally 7th-century text known in full as the Miniugud Senchasa Fher nAlban (Explanation of the Genealogy of the [Gaelic-speaking] Men of Alba), but often referred to more simply as the Senchus. The Senchus outlines the landholdings and military strength of the leading families of the Early Christian kingdom of Dál Riata.14 Those of Islay were said to have been owned by the powerful and implicitly Gaelic-speaking cenél nOengusa (kindred of Angus). As in other parts of Dál Riata, their estates were measured in terms of abstract units known as tech or ‘houses’, not for the purpose of redistributing wealth but to apportion the obligation to supply the kindred’s substantial marine force with boats and men.

Figure 1.2 Suspected Iron Age fortifications.

Since Islay and the surrounding area began to pique the interest of historians in the late 19th century, writers have drawn heavily on observations like these to emphasise the local importance of Gaelic tradition, stressing its essential continuity in an unbroken chain back to the 5th century AD or earlier.15 As a historical narrative, this assumption of continuity is reassuringly simple. It provides a backdrop of cultural certainty against which other developments can be more easily gauged. Unfortunately, its subsequent overstatement has also served to conceal a significant flaw in the underlying body of evidence. With the exception of one terse reference to an earthquake in the Annals of Ulster for 740,16 and a perfuncintroduction tory notice of the death of Manx king Godred Crovan in Islay recorded in the Chronicle of the Kings of Man and the Isles under 1095,17 there are no surviving references to the island itself, let alone the political allegiances or cultural identity of its inhabitants, until the arrival of Somerled in the mid 12th century. This represents an effective hiatus of 400 years in the local historical record. While the Islay that emerged from this extended repose could certainly be described as Gaelic, balancing the written accounts that frame the gap against other types of evidence suggests that the expression of that identity had changed dramatically since Dál Riatan times. It is, of course, no little coincidence that this black hole in Islay’s history corresponds to the era of overseas expansion from pagan Scandinavia more commonly known as the Viking Age.

The term ‘Viking Age’ is a nebulous one, the temporal span and implications of which vary from region to region. In this volume, it will cover the period of pagan Scandinavian raiding, settlement and cultural influence from the time of the first recorded raids in the Hebrides in the last decade of the 8th century to the ‘official’ Conversion of the neighbouring Northern Isles by the Norwegian king Óláfr Tryggvason in the last decade of the 10th. The term ‘Viking’ itself is also fraught with pejorative connotations.18 Here, it will be used as a simple pronoun interchangeably with ‘Norse’ and ‘Norseman’ to stand in place of ‘pagan Scandinavian’ or, more specifically, their military elite. For reasons discussed in Chapter 4, the language spoken by these Vikings will be described as Old Norse (ON), and that of their Celtic counterparts in the Hebrides as Gaelic.

With Scandinavian disruption to the political status quo during this period playing such a pivotal role in the crystallisation of the medieval kingdom of Scotland, 19 it would be surprising if at least some impact had not been felt in Islay and the Inner Hebrides. This much is suggested by the transformation of the designation ibd(a)ig (Hebrides) in the Irish annals of the pre-Norse period,20 to the Innse Gall, (Islands of the [Scandinavian] foreigners) encountered towards the end of the Viking Age.21 It also seems to be mirrored in the martial culture of the region’s political elite.22 Although scant illustrative detail survives from the Dál Riatan period, what remains from the Lordship of the Isles shows clear signs of Scandinavian influence. While the naval levies of the Senchus are thought to have comprised wooden-framed, hide-covered currachs, for example, the mainstay of the Lordship’s fleets, the birlinn or West Highland galley, appears to have evolved from the clinker-built Viking longship, differing mainly in the addition of a fixed rudder.23 Even the word birlinn, from Scottish Gaelic bìrlinn (f), has Scandinavian origins, deriving ultimately from Old Norse (ON) byrðingr (m) meaning ‘ship of burden / merchant ship’. Similar comparisons can be drawn with the battle gear of Hebridean nobles depicted on the West Highland grave slabs at Finlaggan and Oronsay,24 and the conditions of ship service recorded in local charters of the Early Modern period, such as the 1614 Tenandry of Lossit.25 But there are also hints at a far more deep-reaching change.

As the written records for the area become more plentiful, it becomes clear that the language of the Lordship had diverged substantially from that of Ireland since the Early Christian era.26 While this divergence could be attributed to a number of factors as diverse as natural drift or the growing influence of English, there are strong indications that the main agent of change was, in fact, Old Norse, the language of the Vikings. Linguistic studies highlighting traces of Scandinavian ‘interference’ in the vocabulary, syntax, grammar and pronunciation of the Hebridean dialects of Gaelic are not new.27 Since the turn of the millennium, however, the systematic review of these features by a new generation of historical linguists has traced their genesis to native speakers of Old Norse learning Gaelic, as opposed to native speakers of Gaelic adopting aspects of the Scandinavian language.28 This is a prospect that implies a profound change in the composition of Hebridean society during the Viking Age. The most straightforward explanation is large-scale and long-lasting Scandinavian settlement. As we have already seen, the incoming Scandinavian nobles would have had good reasons to seek control of islands like Islay. But with the indigenous Celtic elite under severe cultural pressure to maintain a monopoly on land ownership, and having access to a range of military resources to help them do so, it is difficult to see how equilibrium could have been achieved without significant social upheaval. Whereas small-scale Viking settlement would have been repelled or quickly absorbed into the Gaelic mainstre...