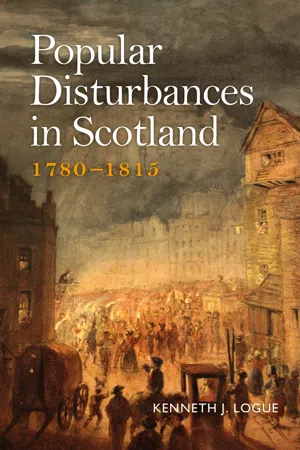

![]()

1

Meal Mobs

Montrose — Winter, 1812–13

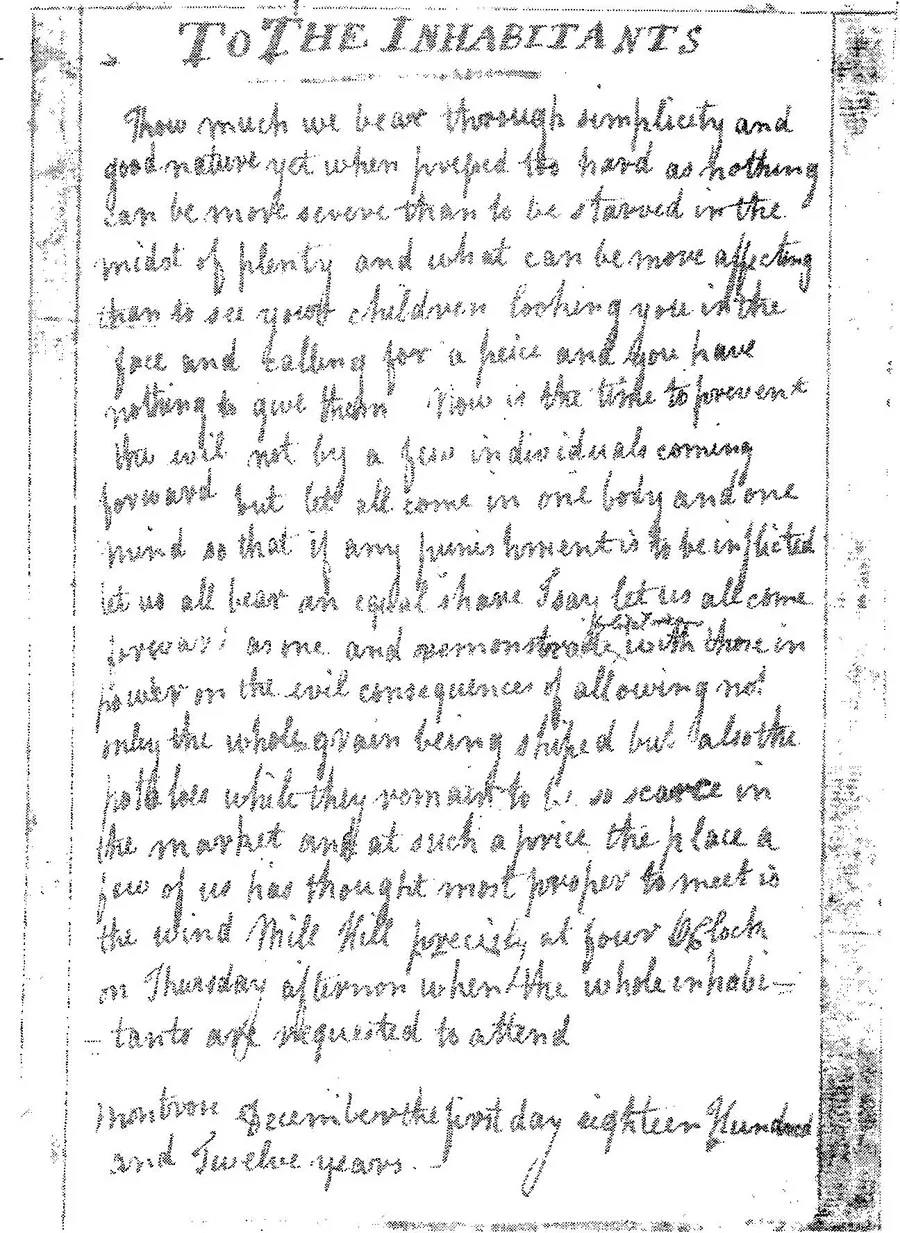

ON 1 December 1812, a placard appeared on the walls and in the streets of Montrose, calling a meeting of all the people on Windmill Hill to do something about the shortage of meal and its high price —

Now is the time to prevent the evil, not by a few individuals coming forward but let all come forward in one body and one mind so that if any punishment is to be inflicted let us all bear an equal share. . . .

The day after this placard was put up the town magistrates banned the meeting, urging the merchants, manufacturers, tradesmen and other responsible inhabitants to keep their servants and children at home and to be prepared to assist the magistrates. A second series of placards altered the venue of the meeting to the Constable Hill, which was outside the magistrates’ jurisdiction and the meeting went ahead. The excitement shown there was the prelude to two months of disturbances aimed at stopping the export of grain from the harbour of Montrose. Popular feelings against this export ran very high and are illustrated by an incident a few days after the Constable Hill meeting. A group of Montrose merchants saw a local woman, Barbara Lyall, emerging from a tinsmith’s shop and when they approached she told them

she had been getting her horn repaired and on their attempting to Ship Grain she would blow it when Five hundred people would assemble and would fight to the last.

The final clash between the people and the local authorities did not occur until 23 December 1812. William Shand, a local grain dealer, decided that he would export a cargo of grain from Montrose to Leith and he chartered the Barbara to do so. As the carts were on their way from Shand’s granaries on the east of the town to the harbour which lay to the south through the back streets, they were intercepted by a large crowd. Women in the crowd seized the bridles of the horses and turned the carts round, then escorted them back to the granaries. There some of the women loosened the necks of the sacks and threw them on the ground to empty out the grain. Those carts which were found to be carrying barley and not oats were allowed to carry on to the harbour. While the grain, mainly the barley but also some loads of oats, was being loaded aboard the Barbara, another crowd of women insulted and abused the vessel’s captain, John Mearns. One woman threatened to throw him over the pier and burn his ship before morning if he did not desist from taking the grain on board. In the course of all this action five women were arrested and lodged in the Tolbooth: the Provost and Magistrates, however, were quickly besieged in the Town Hall by a very large and hostile crowd and they prudently decided after some official investigation to release the prisoners. No further cargoes of grain were shipped from Montrose until 19 January and the object of the crowd activity was achieved for a time.

Fig 4. Handbill, Montrose, 1st December 1812, ‘To the Inhabitants’. Copyright Scottish Record Office, JC26/360.

Just over a week later the Provost and a few others decided to call a meeting to consider measures to open the grain market and supply the town with meal. The meeting, held on 4 January, made two basic and important decisions. Firstly they decided that the best way to supply the market with meal was to raise the prices in Montrose, which until then had been lower than those in neighbouring towns, to a level equal to the average prices of Dundee and Arbroath. This, it was felt, would encourage those who were withholding their meal or sending it elsewhere because of the low price to start supplying Montrose again. While this decision meant an increase in price to the local consumers, it might have been acceptable to them in that it meant a supply of essential food. The second decision was almost certainly unacceptable: ‘In case the Dealers are disposed to ship their Grain,’ they decided, the Magistrates would use every means at their disposal, including the use of the large number of newly enrolled special constables and the summoning of military aid, to ensure that the shipping of grain was not prevented by the mob. This meeting seems to have been an attempt to break out of a vicious circle. Around 23 December, when the first disturbance took place, the farmers of the area had agreed to supply Montrose with 3,000 bolls of meal for the town’s summer consumption — as long as the markets were kept open and the export of grain was allowed. For two weeks no deliveries of meal or grain were made to the town because the people were riotous and the corn merchants would not buy grain if they could not be sure of exporting it in safety. Thus, as long as the markets were not supplied with meal at a reasonable price, the people would not allow any grain to be exported and, as long as the people refused to allow exports the farmers would not supply the markets. The 4 January meeting, by raising the prices in the market and promising protection to the exporters, solved part of that problem by giving the farmers inducements to supply the markets and the corn-merchants protection for their profitable exports, but did not convince the people that there would be a secure supply of meal at a reasonable price.

Map 1. Montrose, c.1812.

On 8 January the second attempt to ship grain was made and the Sheriff-Substitute, Magistrates and special constables assembled for that purpose. The town carters, having refused to carry any grain at all, were called to the Town Hall where they promised to attend with their carts ready to assist in loading grain. In the event, however, they failed to do so, some finding they could not yoke their carts because their wives had locked the stables or sent the horse away, while others simply refused to undertake the hazardous business in the face of popular feeling. Some of the constables were also reluctant to enforce the shipping of grain against popular opposition, but they were told that they were duty bound to act. To make matters worse for the authorities, the shipmasters resolved ‘not to Ship any Grain which was brought to them accompanied by a force on account of its being dangerous to their vessels’ Faced with this situation, the corn merchants said they were reluctant to ship without military assistance. Since the Provost had written a few days before for two hundred soldiers, it was eventually decided to await their arrival. The Magistrates and others then retired to the Star Inn, followed by a large crowd of townspeople, who shortly began to stone the inn and any farmers or corn merchants who ventured within range. With this exception, the next ten days passed off quietly and no soldiers arrived.

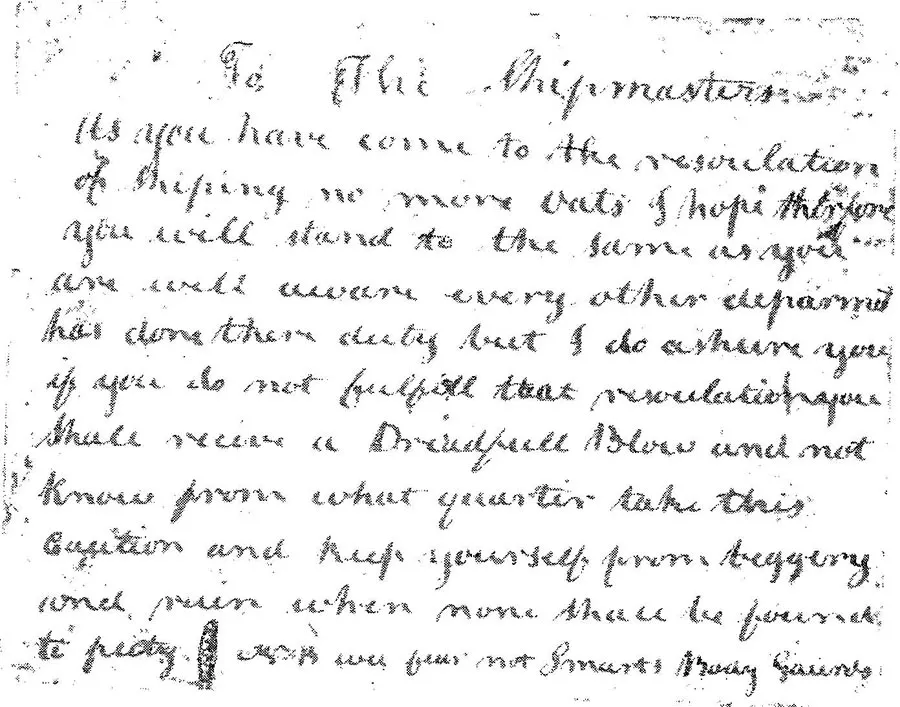

Placards did, however, appear on 18 January, urging the people to continue their opposition to the shipping of grain. Another placard was addressed to the shipmasters:

TO THE SHIPMASTERS

As you have come to the resoulation of Shiping no more Oats I hope therefore you will stand to the same as you are well aware every other departmet has done there duty but I do ashure you if you do not fulfill that resoulation you Shall recive a Dreadfull Blow and not know from what quartir take this caution and keep yourself from beggery and ruin when none shall be found to peity N.B. wee fear not Smarts Body Gaurds.

On the day that these appeared — coincidence can be discounted — Adam Duff, Sheriff of Forfarshire, arrived in Montrose to arrange for the next attempt at shipment, this time with the military support of the 70th Regiment of Foot. They were drawn up in reserve on the Links between the town and the sea.

On the morning of 19 January, the day fixed for resolute action on the part of the authorities, the town carters were again summoned to the Town Hall and warned that they would be struck off the list and deprived of their licences if they did not act. At the same time they were assured that any damage suffered while carting grain to the harbour would be made good by the Town Council. In spite of these warnings and assurances, when the Sheriff, Magistrates and about a hundred constables arrived at the granaries, not one of the town carts was there and the operation had to rely on about six carts brought in from the country. When these few carts were loaded up, the constables began to escort them towards the harbour. The route from the granaries to the shore passed close by two small hills, the Windmill Hill and Horologe Hill, and it was here that the small convoy met with the stiffest popular opposition. Some of the crowd on Horologe Hill, apparently led by Robert Ruxton, a Montrose tailor, dragged several boats from the beach and laid them across the road between the hill and Birnie’s Yard to stop the carts. When the boats were in position, many of the women ran back to the beach ‘and filled their laps with stones’. In order to clear the way for the carts, a detachment of the 70th Foot was sent to the hill to disperse the crowd. The Riot Act was read, but only after Elizabeth Beattie tried to snatch it from the Magistrate and called out, ‘Will no person take that paper out of his hand?’ With some difficulty the soldiers pushed the crowd back from the barricade of boats, allowing them to be cleared to the side and letting the carts pass. When the carts emerged on to the shore they were faced with more angry townspeople who were being held back by some of the constables and another party of soldiers at the foot of the various wynds and alleys which issued on to the harbour area. The Riot Act was again read to the crowd, probably to convince them that the authorities meant business, and the first cartloads of grain were successfully taken on board one of the ships. The procedure having succeeded once, it was repeated and continued all that day and into the next. The crowd also continued its opposition to the loading but on the second day changed its tactics. Some of the townspeople assembled at the north end of the town in an attempt to stop and turn back the cartloads of grain which were arriving from the farms in the area now that export was taking place. At first this move worked and some carts were turned back. This was soon successfully countered by a party of constables who rode farther out of town to catch the carts and escort them back through the crowd.

Fig 5. Handbill, Montrose, January 1813, ‘To the Shipmasters’. Copyright Scottish Record Office, JC26/360.

When this final attempt had been made by the crowd and had failed, the shipping of grain was allowed to go on without serious disruption. Robert Ruxton, who seems to have been the most active member of the crowd, admitted defeat on the first day of the disturbance when he and an unidentified woman made an unsuccessful trip to Brechin to try to get support from the people there. Ruxton went first to the Convener of Trades in Brechin and asked for his support, but this was refused. He told Thomas Fraser that ‘he wanted down the assistance of the Brechin people to Montrose as the people there had been overpowered’. It was dark by now and few people were about in the town; Ruxton blew his horn in an attempt to attract some attention but this had no effect. On his way into Brechin he had told William Laing the toll-keeper that ‘it was all over with them unless they got some hundreds of people from Brechin’. No one accompanied him back to Montrose, and it was indeed all over. Eleven people were arrested in the next few days, and six of them, including Ruxton the tailor, were committed for trial. At the Spring Circuit in Perth on 20 and 21 April 1813, Ruxton was found guilty of mobbing, rioting, instigating, encouraging and collecting a mob and was sentenced to transportation for seven years. Of the rest only two actually stood trial. They were Jean McMillan and Elizabeth Beattie, who also played prominent parts in the disturbances — at least they were very noticeably and frequently in the front line of the crowd. Both were found guilty of less serious charges and sentenced to six and four months respectively in Forfar Tolbooth.1

The Food Riot

The food riot was the most common type o...