![]()

1

The Power of Squirrel Nutkin

I was always a child of nature and was extremely fortunate to spend part of my early childhood in one of the richest wildlife areas of the British Isles. There can be little doubt that I owe my parents an enormous debt of gratitude for living in some of the glorious places that they chose as home. Being steeped in nature from as far back as I can remember has helped to forge my undying, lifelong passion and my way of life as a writer and photographer in a bid to help others discover that precious connection with wildlife.

Fifty miles due west of Fort William lies the rock-hewn Ardnamurchan peninsula. This, the most westerly mainland point in the country, is a place of savage beauty, diverse in its land and seascapes, surrounded on clear days by sweeping views to the Western Isles, and to some of Scotland’s great mountain vistas, including the Skye Cuillin, Knoydart and the wind-scoured ridges of Torridon. Gale-battered Atlantic oak woodlands fringe the peninsula, providing an unsurpassed environment for a host of living things including rare invertebrates, flora, mosses and bryophytes, as well as fabulous fauna: red deer, golden and sea eagle, wildcat, pine marten, otter, fox and badger. Though at the end of the 1960s I grew up surrounded by an unequalled diversity of wildlife that I often encountered on a daily basis, the red squirrel was missing.

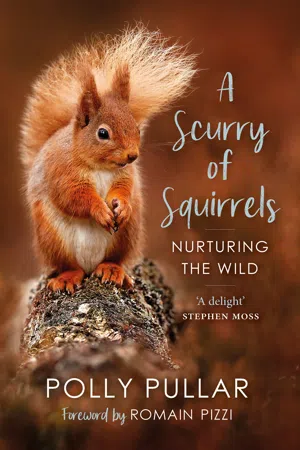

However, the red squirrel has been a part of my psyche for as long as I can remember, because I was reared on the tales of Beatrix Potter, and count these as amongst the very finest works of children’s literature. They are highly entertaining for grown-up readers too. The fact that Potter wrote the stories and created the artwork is important. The marriage of words and pictures is unsurpassed. Her illustrations are entrancing, and often skilfully humorous. Though in most cases she anthropomorphises her animals, and her stories depict them behaving like us while dressed in clothes, her shrewd naturalist’s eye ensures that each is perfectly portrayed, with an attention to critical detail that reveals very real facets of its wild character. Undress her subjects and what lies beneath is astonishingly accurate. Squirrel Nutkin has long been one of my favourite Beatrix Potter figures. Like most of the handreared squirrels I have been fortunate to spend time with, Nutkin is a little devil overflowing with mischief and playfulness.

When The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin was published in 1903, naturalist Potter probably had no idea that her brilliant squirrel portrayals and her clever words would be a catalyst that began to change our point of view. Some fifty years later, another red squirrel was a crucial player in the evolution of our attitudes towards red squirrels. Tufty became the figurehead for a road safety campaign aimed at small children. When I was six years old I was made a member of the Tufty Club and wore my badge with pride. I still have it. Now when I see an increasing number of pathetic little red squirrel bodies dead on our busy roads, it is heartrending to witness that the Tufty Club’s wise message for children can do nothing to protect the vulnerable relatives of its cult hero.

It was not until I was nearly nine and sent away to a small all-girls boarding school set on a wooded Perthshire hillside at Butterstone, near Dunkeld, that I began what has since proved to be one of my wildlife love affairs.

Hating being away from home and suffering from acute homesickness and the instabilities surrounding the pending separation and subsequent divorce of my parents, to the staff I must have been the problem child. I was more intrigued by the birds in the garden than the lessons and I was permanently crying because I missed home and our family’s large menagerie so much. A finicky eater, I hated the school food too: stodge, stodge and more stodge. We were not allowed to take food back to school with us but we could take birdseed and nuts to put out on various bird tables in the grounds, and I constantly asked my parents for more supplies. I sometimes got so hungry, having been repulsed by the proffered meals, that I ate the birds’ food to stave off my hunger pangs instead. Nuts have remained a favourite food ever since. Compared to the freedom I had experienced in Ardnamurchan, now there was a strict new regime and there were also two ‘big’ little girls who were bullies, and who teased me incessantly. I simply wanted to go home. When I look back over it, I realise that Butterstone was not a bad place. Its setting is idyllic for a nature-loving child, as it is surrounded by oak woods and freshwater lochs where I quickly discovered that there was plenty to take my mind off my yearning to go home.

My inauguration at boarding school began in September. I remember that for the first few miserable days after term had begun, it rained incessantly. I kept diaries – hardly literary gems: ‘It rained again. Missed mummy, Ginger (my pony) and the dogs. School food is horid. Bridget said she might be my frend.’ An Indian summer then followed this damp tear-soaked start, with balmy days that made the landscape glow as swathes of rosebay willowherb set loose their fluffy seed heads to float in the breeze. The surrounding forests blended to a palette of yellow, ochre and bronze, and jays shrieked as they flew in bounding flight on their acorn-collecting forays, filling the air with the sound of tearing linen. Then one morning at break time when we were playing in the garden I saw a red squirrel swinging on the peanut feeder of our bird table. I remember it vividly because instantly it seemed so similar to Squirrel Nutkin, particularly as it then leapt onto the table and sat up to eat, holding nuts in what I saw as its perfect little furred hands. That night my diary entry read: ‘Saw my first squirel – it is so beautiful I cannot believe it. It looked Soooo like Squirrel Nutkin.’ And thus began another journey.

My homesickness began to ease and I even found myself eagerly anticipating playtimes so that I could go out into the garden and the school’s extensive surroundings to look for squirrels. They were plentiful and the more nuts we put out, the more seemed to come. They were often there very early in the mornings but there was never time to go out before breakfast, and by the midmorning break time they had usually gone. They had a routine and after an early start they returned at lunchtime and then again at teatime, but in winter as the days became shorter and shorter, their visits tended to be harder to time.

In the early mornings and late afternoons, fallow deer emerged shyly from the shadowy woods too. Though I was very familiar with our two native deer species in Ardnamurchan – the red and the roe – I had never seen fallow before. Their four colour variations intrigued me: common – rusty brown with speckles; leucistic – a pale cream colour; menil – with spots and dark brown around their tails rather than black; and melanistic – a really dark brown form. The gardener always complained that they ate his flowers. Sometimes he mumbled and grumbled because they also left little heaps of shiny black currants around the grand front door entrance. It always made me giggle. I had a pet sheep back home called Lulu and she did the same thing around the doorways of my parents’ hotel in Kilchoan. Only sometimes she also went right upstairs and left currants outside guests’ bedrooms. This was unappreciated.

We were allowed to build dens in the huge grounds, and the rhododendrons and an unruly stand of bamboo made perfect places for foundations for superb structures. However, I usually played by myself and made dens further out on the edge of the garden specially for watching the red squirrels and the fallow deer.

Living in such a beautiful landscape meant that nature education was a positive and prominent aspect to our time at Butterstone. We had a large nature table and were encouraged to bring things in for everyone to share and talk about. I asked cook for a jam jar with holes in its lid so I could keep a chrysalis I had found and we could watch it transform into a lovely moth. I excelled at nature education, art, English and reading, and was pretty bad at everything else because I found the teachers boring. We could also watch the birds and other animals from the windows, and even had walks into the out-of-bounds areas of the woods in spring to listen to birdsong. By May the cuckoo would arrive, and once I saw a tiny willow warbler struggling to keep pace with the gluttonous appetite of its obese fostered cuckoo chick. So though to begin with I hated being away from home, there were bonuses.

There were also regular school outings to nearby Loch of the Lowes. The Scottish Wildlife Trust purchased this nationally important wooded wetland site in 1969 and it has since become their flagship reserve and is in particular famous for its breeding ospreys. Soon after the purchase, a pair of ospreys conveniently turned up. On my initial school visit the spring after my first term, small groups of us were allowed to clamber up into a shoogly hide built on stilts to watch these magnificent fish-eating raptors. Without proper binoculars or telescopes at that early stage of the reserve’s development, and no cameras on the eyrie, it was primitive compared to the way every midge, every buzzing fly, the piping of an egg as it begins to hatch, and the diamond beads of raindrops on a sitting bird’s ruffled feathers can be viewed today right around the globe by anyone with internet access. While the ospreys were fascinatingly exciting, particularly as the reserve’s warden related the story of how these migrating birds that returned to Scotland to breed in spring had been persecuted to near extinction, it was the red squirrels that captivated me. At Loch of the Lowes some of them were so tame that they would come and take peanuts from our hands, providing we kept very still and quiet. When it involves wild things and wildlife-watching, oddly, though I am told I am a keen talker, I have never had a problem with keeping quiet. The squirrels in the school grounds were wisely wary. This was no surprise, given the racket made at playtime by a lot of shrilly shrieking little girls. However, I realised that if I broke away on my own from the team games we played in the garden, and instead went off to the woodland fringes and hid myself in my den, it was different. There I put out food on the old crumbling drystone wall, and the squirrels began to venture in closer and closer. I soon attracted enchanting little wood mice and bank voles too. One day a weasel popped its foxy little face from out of a mossy hole in the wall. Its body was like a piece of elastic. I began to recognise individual squirrels and could see that each was unique, that its mannerisms and the particular way that it interacted with the other squirrels was different too. Some had very blonde tails and flamboyant ear tufts, while others had lost these wonderful extra head adornments. Most of them preferred to be there alone and would not tolerate imposters on this new food supply; they clearly were under the impression it was theirs entirely. Squirrels are no different to people, and each has a unique character and its own particular behavioural traits. Some were more tolerant than others but in most cases, if another squirrel dared to try to venture in then it was swiftly chased away with a flurry of angrily waving tail and loud squirrel bad language. Incidentally, red squirrels have quite a temper. They are also surprisingly vocal, and won’t hesitate to let you know when they are displeased, or particularly content. With fast tail flicking and irate chitter-chatter, an imaginative watcher can easily translate this to a squirrel’s version of ‘go forth and multiply’, for that is exactly what they mean. Some of my little visitors quickly became bolder and bolder, and bounded up close to me, while others remained edgy. It filled me with a frisson of excitement that I still feel every time I view any wild thing from a close perspective.

The gardener had a large cat, and one morning it narrowly missed catching one of the squirrels as it was burying nuts on the lawn. Sometimes that damn cat would appear with birds poking from its gaping jaws, pathetic little feathers soggy with feline spittle. And it tortured and teased mice, patting at them with its fat paws, and sometimes throwing them into the air before it finished them off. And worse still, one wet morning I saw to my horror that it was carrying a squirrel’s tail. I began to hate that bloody cat, and got into trouble for referring to it as such to one of the teachers. I was made to write pages of pointless lines that said: I must not swear, because it is rude. I have been worrying about the effects of domestic cats and dogs on squirrels ever since. Though squirrels are nature’s finest trapeze artists, they are sometimes woefully un-streetwise when on the ground and come to grief all too often.

When my parents – separated by now – independently came to take me for sporadic day’s out from school, it invariably included a visit to Loch of the Lowes. I had told them that the squirrels there would feed from our hands. They certainly enchanted my father during a visit one afternoon in late autumn when we were lucky to watch several of them having a final feed before they vanished back to their dreys for the night. One of them landed on his bald head. Afterwards we sat in a hide in the pinkly transforming dusk as smoky trails of mist spread over the loch, drinking tea from his thermos flask to the accompaniment of the cacophony of hundreds of wintering greylag geese splashing down onto the water to roost. That Christmas holiday I went to spend a few days with Dad. Following my parents’ separation, he had moved temporarily to London and he took me to see a ballet, The Tales of Beatrix Potter. Squirrel Nutkin’s performance on stage left me in no doubt that with the exception perhaps of the rare great crested grebe, a bird I had also seen at Loch of the Lowes, the red squirrel was indeed the finest dancer in the natural world.

![]()

2

Bough Lines

The red squirrel has been in the British Isles for a very long time. Fossil remains found at the end of the last Ice Age from some 12 million years ago reveal a similar mammal to the one we now know. The Latin name of the red squirrel is Sciurus vulgaris and the name squirrel comes from the Greek skiouros, meaning a shadow, and oura, a tail – shadow tail. Old local names are more prolific south of the Scottish border and include scorel, squerel, skuggie, squaggie, skoog, swirrel, squaggy, scrug, skarale and scuggery. These are likely to have evolved through the different pronunciations of our richly diverse regional accents all around the British Isles. Puggy has little similarity to the others but often appears in old documents. When I was at school and first encountered squirrels we used to refer to them affectionately as squigs, and the name has stuck. I still find myself using it on occasion as in, ‘I am just going out to feed the squigs.’

The red squirrel’s Gaelic names are feòrag and toghmall. Though the translation may be hazy and open to various interpretations, some of which refer to its woodland home, the best and most appropriate is ‘the little questioner’. Given the extraordinary inquisitive nature of the squirrel, this translation fits it perfectly.

The French word for squirrel is écureuil, and in German it is Eichhörnchen or Eichkätzchen – literally meaning oak kitten, a name that aptly depicts an animal with an incredibly playful ‘kittenish’ spirit that is also often associated with oak trees. We use the term ‘squirrel’ as well as ‘magpie’ to describe someone who hoards or collects things. This is due to the squirrel’s habit of caching and burying food for the winter. We ‘squirrel’ things away – special food items or perhaps precious items we don’t want to share with others. Incidentally, the magpie has been known to steal items of shiny jewellery that have been left close to open windows, but the squirrel does not have the same attraction to such things. Use of the word ‘con’ for a squirrel is commonly found in dusty Victorian natural history tomes, and was employed in parts of England as well as in Scotland.

Collective nouns for animals and birds have always fascinated me. For squirrels it is a scurry, or occasionally you may find reference to a drey of squirrels too – which does not seem very imaginative, given that this is the name of their nest. However, I have often thought that a knot of squirrels would also be appropriate. Having hand-reared numerous litters of kits, when they are asleep together they become so entwined that it can be impossible to see which body part belongs to which little squirrel as they bind themselves tightly together as if in a beautiful tight knot.

Considering the long love-hate relationship that has surrounded the red squirrel, it is perhaps surprising that its association with folklore appears to be largely non-existent. Squirrels do, however, feature as heraldic symbols and their presence on a coat of arms, usually sitting and holding a nut or acorn, is thought to symbolise caution, thriftiness and conception. Depictions of squirrels as heraldic symbols were far more prevalent for families from the north of England; although the Earl of Kilmarnock – family name Boyd – had two squirrels on the family coat of arms, and squirrels also occur on the seal of Robert Boyd, Lord of Kilpoint in 1575, their presence for a Scottish family is thought to be unusual. While mammals such as the hare have always been revered and feared, viewed as totems, signs of good fortune, and conversely of impending doom, given both our turbulent relationship with the squirrel and its numerous charms, it seems odd that it has not captured people’s imaginations in the same manner as other animals.

Ever since its arrival in Britain around 10,000 years ago, it would seem that this is an animal that has always been battling for survival. It has come dangerously close to extirpation on far too many occasions. Much of this is due to a constantly changing woodland environment, but disease and relentless persecution have played their part too. While species such as our largest land mammal, the red deer – also primarily a mammal of woodlands – can adapt to a life without trees, this is not the case for the red squirrel. Without healthy forests, red squirrels stand no chance.

The sylvan history of the British Isles is one of frequent deforestation. Since Neolithic times woods have been harvested, replanted, and often cleared entirely, initially to make way for early pastoral and agricultural activities. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries major timber-felling pushed squirrels to the edge, and during this era they vanished entirely from Ireland. In some places woods were even purposely razed by fire. Some were torched to drive out enemies during battles. Other enemies included the wolf. Before it was annihilated from our midst during the eighteenth century, tragically entire forests might also be burned in a bid to kill it. Inevitab...