- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1858, Mary Millburn successfully made her escape from Norfolk, Virginia, to Philadelphia aboard an express steamship. Millburn's maritime route to freedom was far from uncommon. By the mid-nineteenth century, an increasing number of enslaved people had fled northward along the Atlantic seaboard. While scholarship on the Underground Railroad has focused almost exclusively on overland escape routes from the antebellum South, this groundbreaking volume expands our understanding of how freedom was achieved by sea and what the journey looked like for many African Americans.

With innovative scholarship and thorough research, Sailing to Freedom highlights little-known stories and describes the less-understood maritime side of the Underground Railroad, including the impact of African Americans' paid and unpaid waterfront labor. These ten essays reconsider and contextualize how escapes were managed along the East Coast, moving from the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland to safe harbor in northern cities such as Philadelphia, New York, New Bedford, and Boston.

In addition to the volume editor, contributors include David S. Cecelski, Elysa Engelman, Kathryn Grover, Megan Jeffreys, Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, Mirelle Luecke, Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Michael D. Thompson, and Len Travers.

With innovative scholarship and thorough research, Sailing to Freedom highlights little-known stories and describes the less-understood maritime side of the Underground Railroad, including the impact of African Americans' paid and unpaid waterfront labor. These ten essays reconsider and contextualize how escapes were managed along the East Coast, moving from the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland to safe harbor in northern cities such as Philadelphia, New York, New Bedford, and Boston.

In addition to the volume editor, contributors include David S. Cecelski, Elysa Engelman, Kathryn Grover, Megan Jeffreys, Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, Mirelle Luecke, Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Michael D. Thompson, and Len Travers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sailing to Freedom by Timothy D. Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Massachusetts PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9781625345929, 9781625345936eBook ISBN

9781613768495Introduction

Timothy D. Walker

This volume of curated essays focuses exclusively on the maritime dimension of the Underground Railroad, as antebellum pathways to freedom for enslaved African Americans have collectively become known.1 The contributors examine and contextualize the experiences of many enslaved persons in the United States who, prior to the Civil War, fled to freedom by sea and of the people who facilitated those escapes. Maritime escape episodes figure prominently in the majority of published North American fugitive slave accounts written before 1865: of 103 extant pre-Emancipation slave narratives, more than 70 percent recount the use of oceangoing vessels as a means of fleeing slavery.2 Similarly, in William Still’s classic, widely read account of his activities as an Underground Railroad “Station Master” in Philadelphia during the mid-nineteenth century, many of the most striking engravings that accompany the text illustrate dramatic descriptions of waterborne, maritime escapes.3 Clearly, the sea should rightly constitute a central component of the full Underground Railroad story. But the topic remains surprisingly understudied. Maritime fugitives have drawn minimal attention in the historiography of the field, and the specific nautical circumstances of their flight garner little discussion in classrooms when the Underground Railroad is taught.4

To date, public scholarship, academic research, and pedagogical materials examining the Underground Railroad have focused almost exclusively on inland, landlocked regions of the United States. Such publications highlight and prioritize persons who used overland routes and interior river crossings, often traveling clandestinely by night, as they sought to escape enslavement in the Antebellum South. However, recent academic historiography and public history research for museum exhibitions amply demonstrate that, because of the myriad practical difficulties consequent to being a northbound African American fugitive fleeing through hostile slaveholding territory, where vigilante patrols for escapees were an ever-present danger, successful escapes overland almost never originated in the Deep South.5 In fact, prominent Underground Railroad historian Fergus M. Bordewich states flatly, “Escape by land from the Deep South was close to impossible.”6 Instead, the extant scholarship shows that the overwhelming majority of successful overland escapes were relatively short journeys that began in slave states (Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri) sharing a border with a free state (Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa).7

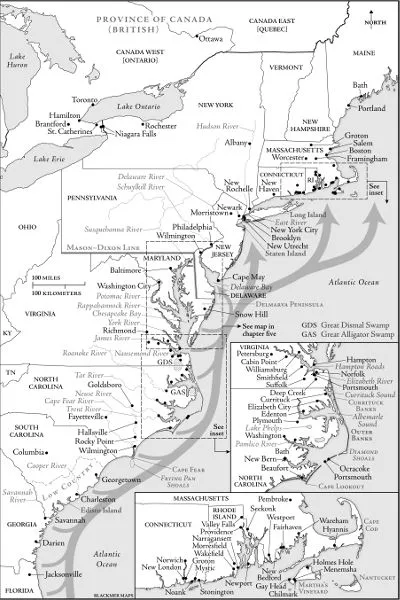

Figure 1. Principal Underground Railroad Route Maps, Overland and Seaborne, with an Emphasis on Ports, Inlets, and Waterways of the Maritime Underground Railroad. Maps by Kate Blackmer.

What has been largely overlooked, however, is the great number of enslaved persons who made their way to freedom by using coastal water routes (and sometimes inland waterways), mainly along the Atlantic seaboard but also by fleeing southward from regions adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico. Because most historians of the Underground Railroad typically have not cultivated a maritime dimension to their research, they have generally neglected this essential component of the Underground Railroad, leaving the sea out of the various means employed to convey enslaved persons to the northern free states and Canada. Such neglect is deeply unfortunate; the absence of a detailed assessment and understanding of the maritime dimension of the Underground Railroad distorts the broader historical picture and hinders the formation of a more-accurate and -comprehensive knowledge of how this secretive, decentralized “system” operated. A revision of the traditional land-bound view of the Underground Railroad is therefore long overdue. This volume is intended to address this lacuna.

Research undertaken and presented for a series of “Landmarks in American History” workshops was sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities and realized through the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. The series, titled “Sailing to Freedom: New Bedford and the Underground Railroad” and running from 2011–2015, demonstrated that a far larger number of fugitives than previously supposed actually escaped bondage by sea—especially those fleeing from coastal areas in the far South, where the employment of slaves in diverse maritime industries was ubiquitous. (The far South was any slave region that lay beyond a relatively close journey by foot to the permeable border zones where slave states lay adjacent to free states.) Enslaved laborers worked as shipyard artisans, quayside stevedores and longshoremen, river boatmen and ferrymen, coastwise cargo-vessel crewmen, and estuary or near-coastal fishermen, among many other occupations connected to the water. Such work allowed enslaved persons to develop expert seafaring skills and knowledge in myriad areas: handling watercraft; gaining a detailed knowledge of coastal geography and hydrography (currents, tides, channels, navigation hazards); and establishing direct or indirect contacts with ocean-going ships’ crews from northern free states. Equally valuable was their ready access to vessels heading out to sea. For enslaved persons in the southern Virginia and Maryland tidewater areas, the Carolina Low Country, and the Georgia and Florida seaboard, or along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, escape by water was the logical option and, in reality, the only viable way to achieve an exit from their enslaved circumstances.

The new scholarship presented in this volume convincingly establishes that a markedly high proportion of successful escapes from the slaveholding South to sanctuary in the North were achieved using coastal seaways rather than overland routes. It is tempting to argue deductively that, given the circumstantial evidence, potentially even the majority of North American escapes from enslavement may have been accomplished by sea, but absent a definitive body of statistical data that would allow for a comparison between overland and waterborne escapes, this point is nearly impossible to prove. Still, of the known and documented fugitives who made successful escapes from the far South, almost all their escapes were achieved by sea.

Unfortunately, there is no way to conclusively quantify clandestine, illegal Underground Railroad activity or to reliably count the precise numbers of fugitive escapees by land or by sea.8 Even so, the research contained in this book establishes definitively that escape by sea must be seen as a significant, indispensable component of the Underground Railroad story. Moreover, this analysis demonstrates that waterborne travel provided the only practical method of escape to a free territory from the coastal far South, because escape by long-distance overland routes would have been in most cases impractical: too slow, too dangerous, too logistically complicated, and therefore unsustainable.9 By contrast, sailing to freedom was relatively simple and less hazardous. Once the fugitive was aboard a northbound vessel, escape by sea was direct; traveling by ship, whether powered by wind or steam, proceeded far more quickly and with much less effort than undertaking any terrestrial journey of comparable distance.10

This maritime fugitive dynamic was not only present but prominent in all slaveholding regions along the U.S. Eastern Seaboard. Consider, for example, the perspective of historian Kate Clifford Larson, a specialist on Harriet Tubman and a contributing scholar of the “Sailing to Freedom” NEH workshops in 2015. Regarding her examination of Underground Railroad activity in and unassisted escapes from one distinct coastal district of antebellum Maryland along the Eastern Shore of Chesapeake Bay, Larson writes:

It is very clear that escapes from anywhere along a water route—not just ports themselves, but rivers, streams, marshes—vastly outnumbered escapes from as little as ten miles away from any shoreline. This doesn’t mean that people were grabbing canoes and small sailboats and sailing away, but rather, they were clearly getting information and making connections that would be valuable for escape. The plantations, homes, small farms, and businesses along the roads that linked villages and towns that hugged the Choptank River (which empties into the Chesapeake), for instance, witnessed hundreds of escapes over the 30-year period before the Civil War. Further inland—10 to 20 miles inland—you see just a few dozen escapes over that period.11

Although not all those hundreds of escaped slaves from along the Choptank River absconded by water—some few fled overland northward to freedom in adjacent Pennsylvania—most did. That being the case, Larson then wondered why historians have not seen “similar [elevated] escape rates from interior [slaveholding] communities?” Scholars of the Underground Railroad, she says, can provide a more nuanced understanding by “exposing the broader and more inclusive resources that maritime communities and workers could offer an escapee—those resources included more than just a vessel, but vital information and connections.”12

Providing a more nuanced understanding is precisely what this volume aims to do. By highlighting the people involved in waterborne escapes, telling their little-known stories, and describing the less understood means by which the nautical side of the Underground Railroad functioned, this work hopes to reshape the overall scholarly view of it, to assemble a more accurate, more comprehensive, and better informed perspective. Taken together, these essays will address an important gap in the scholarly literature of the Underground Railroad and serve to reorient the traditional interpretive framework of scholarship on the topic, broadening it to include little-considered seaborne routes used by fugitives from enslavement in the South prior to the American Civil War.

The primary goal of this book, then, is to build a more authentic and precise description of how two distinct historical spheres—American slavery and maritime experience—intersected, while establishing conclusively through documented cases that enslaved people frequently used waterborne means to escape to freedom. A parallel aim, however, is to reinforce the idea that maritime escapes could be and often were effected without any assistance from individuals who saw themselves as deliberate Underground Railroad operatives. In the nineteenth century, after all, there was little in the way of an organized network to assist would-be freedom seekers in the far South of the United States. The Underground Railroad, according to the prevailing scholarly conception based on available evidence, seems to have functioned as an organized, albeit a loose, network mainly in free northern states.13 Though assisted seaborne escapes from the southern states certainly happened, as indicated in several of the incidents described in the following pages, far more frequently such acts of escape were impulsive and unplanned. Any assistance provided to fugitives was the result of chance meetings, often with persons who were in no way connected to any organized resistance ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Contributors

- Index