- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

New England once hosted large numbers of anadromous fish, which migrate between rivers and the sea. Salmon, shad, and alewives served a variety of functions within the region's preindustrial landscape, furnishing not only maritime areas but also agricultural communities with an important source of nutrition and a valued article of rural exchange.

Historian Erik Reardon argues that to protect these fish, New England's farmer-fishermen pushed for conservation measures to limit commercial fishing and industrial uses of the river. Beginning in the colonial period and continuing to the mid-nineteenth century, they advocated for fishing regulations to promote sustainable returns, compelled local millers to open their dams during seasonal fish runs, and defeated corporate proposals to erect large-scale dams. As environmentalists work to restore rivers in New England and beyond in the present day, Managing the River Commons offers important lessons about historical conservation efforts that can help guide current campaigns to remove dams and allow anadromous fish to reclaim these waters.

Historian Erik Reardon argues that to protect these fish, New England's farmer-fishermen pushed for conservation measures to limit commercial fishing and industrial uses of the river. Beginning in the colonial period and continuing to the mid-nineteenth century, they advocated for fishing regulations to promote sustainable returns, compelled local millers to open their dams during seasonal fish runs, and defeated corporate proposals to erect large-scale dams. As environmentalists work to restore rivers in New England and beyond in the present day, Managing the River Commons offers important lessons about historical conservation efforts that can help guide current campaigns to remove dams and allow anadromous fish to reclaim these waters.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing the River Commons by Erik Reardon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Massachusetts PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9781625345844, 9781625345851eBook ISBN

9781613768419Chapter One

Channels and Flows

In May 1635, colonists from Massachusetts Bay pressed Governor John Hayes, Deputy Governor John Winthrop, and the Court of Assistants, also known as “magistrates,” to create a formal legal code to replace the company charter granted by King Charles I. As the colonial population swelled during the great Puritan migration, John Winthrop noted that “the people had long desired a body of laws, and thought their condition very unsafe, while so much power rested in the discretion of magistrates.”1 To limit the authority of the magistrates and open more space for representative government, the Reverend Nathaniel Ward of Ipswich drafted a provisional compact that outlined the distinct rights, liberties, and responsibilities of men, women, children, and servants within the colony.2 Towns across Massachusetts Bay debated, revised, and amended Ward’s proposal, and in 1641, the Massachusetts General Court—the seat of legislative and judicial authority—accepted The Body of Liberties as the first European legal code in New England. Informed by English common law and Puritan theology, this collection of ninety-eight articles formed the basis for criminal and civil law, which included protections for individual and communal rights to the land and water within the boundaries of the colony. Section sixteen defined public rights to coastal and inland waters, stipulating that “every inhabitant that is a householder shall have free fishing and fowling in any great pond and bays, coves and rivers, so far as the sea ebbs and flows within the precincts of the town where they dwell, unless the free men of the same town or the General Court have otherwise appropriated them.” Above the head of tide, town officials and private landowners determined access to rivers and smaller tributaries, but in 1649 included the exception that “great ponds lying in common . . . within the bounds of some town, it shall be free for any man to fish and fowl there.” The Crown granted the Massachusetts Bay Company exclusive authority over coastal waters and large navigable rivers, within the limits of the corporate charter, with the expectation that colonial leaders held these waters in trust for public use.3 The freemen of the colony, male church members with voting rights, exercised this authority to establish public fishing rights within coastal and inland water and determined rules for entry and exclusion. The Body of Liberties thus adopted legal precedent that gave form to a river commons: a resource open to heads of households within defined, but fluid, colonial boundaries. This declaration of “free fishing” anticipated a rural economic culture that privileged river fishing within the seasonal round of colonial subsistence: livelihoods rooted in the forests, fields, meadows, and waters of the New England countryside.

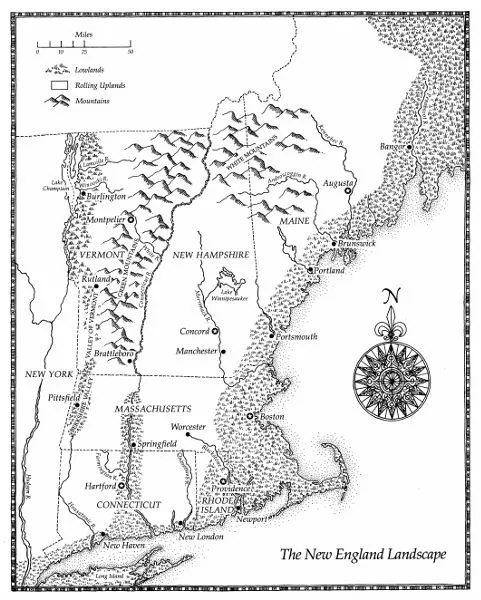

From low-lying coastal estuaries to steep upland channels, New England’s inland waters encompassed a spectrum of river types and ecologies that once sustained a diverse array of aquatic life. As with most watersheds along the Appalachian corridor, rivers begin as small but powerful mountain streams, narrow and straight as they descend through steep-sided canyons. From New Hampshire’s White Mountains, famous for scenic alpine vistas and harsh, unpredictable weather, the headwaters of the Merrimack, Androscoggin, and Saco Rivers flow into wide, U-shaped valleys on their way to the Gulf of Maine. The Connecticut River, the region’s largest watershed, begins north of the mountains with a series of four lakes near the border with Quebec. Also fed by underground springs, swift-moving, shaded mountain streams offer prime habitat for cold-water species like brook trout. As these streams exit mountain elevations they join with a network of wetlands, lakes, and tributaries to form more extensive channels where larger trout mingled with pike and pickerel.4 Leaving the foothills of the north country, these rivers enter broad valleys and meander past forests, rolling hills, and meadows. Along the banks of these large downriver corridors, Indigenous peoples, and later European settlers, tilled some of the most productive soils in the northeast. Rivers transport and deposit sediment, minerals, and nutrients from further upstream that over time create fertile alluvial soils. Indigenous and British colonial riparian communities also harvested the seasonal bounty of the river itself, particularly during migrations of anadromous species.

Figure 1. “The New England Landscape,” in William F. Robinson, Abandoned New England: Its Hidden Ruins and Where to Find Them (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1976), 2.

Diadromous fish migrate between freshwater and saltwater habitats. Referring to the specific direction of their migration, anadromous fish are spawned in freshwater, spend the majority of their lives in the ocean, and then return to the very same freshwater habitat to complete their life cycle. Catadromous species live in freshwater but migrate to the sea to spawn. Over a dozen species of anadromous fish once called the region home, but only one catadromous species, the American eel, is native to the region. To survive such remarkably different aquatic environments, diadromous fish evolved a unique biological mechanism to regulate osmotic pressure—the concentration of water and salts in body fluids. Biologists call these automatic physiological adjustments made between fresh- and saltwater habitats “osmoregulation.” This evolutionary adaptation facilitates diadromous migrations, which in turn allow these species to take advantage of forage opportunities across both freshwater and marine environments. Marine productivity, particularly in the Gulf of Maine, far exceeds that of freshwater habitats, and for this reason biologists theorize that “food availability is an important factor in explaining not only where diadromous fishes occur, but also why fish migrate across the ocean-freshwater boundary, as well as their direction of movement.”5 Though fisheries biologists understand why these species migrate between freshwater and the sea, the question of how anadromous species such as Atlantic salmon traverse vast distances across the open ocean and then return to the exact place of their birth remains something of a mystery.

The return of anadromous fish to their natal waters is one of the most remarkable feats of the animal kingdom. After spending the majority of their lives in the sea, such anadromous fish as Atlantic salmon, shad, and alewives navigate back to the waters where they were born to spawn the next generation. Fisheries biologists disagree as to exactly how these species are able to “home” to the streams and ponds of their birth, but it may have something to do with chemical imprints that guide fish back to natal waters. Nevertheless, the return of anadromous fish provides a boon of marine-derived nutrients to the benefit of other freshwater species and the overall river ecology. Even though the transfer of nutrients is otherwise one-sided, as freshwater brings nutrients to the sea, the anadromous life cycle brings back a small measure of nitrogen and phosphorus as thousands, and in some cases even millions, of fish enter coastal estuaries and begin to swim upstream.6 Historically, New England’s rivers hosted as many as eleven diadromous species, including rainbow smelt, alewives, blueback herring, American shad, striped bass, sea lamprey, shortnose sturgeon, Atlantic sturgeon, Atlantic tomcod, Atlantic salmon, and American eels. Prior to the installation of large industrial dams in the nineteenth century, these species contributed to not only rich, productive riparian environments but also the material welfare of the region’s Algonquian-speaking Indigenous peoples and, by the seventeenth century, British colonial settlers. Three species stand out in the archaeological and historical record for their abundance and prominent position within both Indigenous and Euro-American cultures.

Alewives, a species of river herring and one of the most abundant food fish for Indigenous and colonial communities near the tidewater, were once found along the Atlantic coast from Florida to Maine.7 Beginning sometime around April, alewives begin their journey from the coast to inland spawning grounds, typically calm waters such as small lakes and ponds close to the estuary. Because alewives tend to spawn near the tidal reaches of a river, they offered a predictable source of nutrition for agricultural communities along these well-established migration channels. Both Algonquian peoples and colonial settlers constructed weirs in tidal waters, traditionally made of stone, brush, wooden stakes, and netting, to obstruct and trap fish in a series of small enclosures as they swam upstream. Further upriver, fishermen used seines, large nets extended vertically from the surface to the river bottom, weighted with sinkers, paid out into water with a boat, and then dragged by a company of men back toward the shore.8 Native Americans and British colonists annually caught large quantities of alewives and consumed the fish fresh shortly thereafter or smoked them on large racks to preserve a portion of the catch for future use. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, commercial fishers sent hundreds of barrels of salted fish each year to merchants for sale in urban markets.9 Though fishermen mostly pursued alewives to supplement the household diet and engage with community trade networks, they also supplied bait for New England’s offshore cod fleets. The alewife was one of the most abundant and sought-after anadromous species, and records indicate that alewife runs stayed relatively strong well into the nineteenth century. Raymond McFarland estimated that New England fishermen collectively landed nearly ten million alewives in 1880 alone.10 With spring alewife runs sometimes numbering in the millions, both Indigenous and colonial settler communities celebrated the beginning of the seasonal alewife run as a symbol of the coming spring season. To this day, locals and tourists alike gather to witness half a million alewives migrate up a small stream in Damariscotta Mills, Maine.11

Colonial and early national fishermen expended the most energy and resources during the migration of American shad, the largest species of the herring family. From April to June, shad journey back to freshwater. Their migrations can extend hundreds of miles into the interior, where they remain in freshwater for several months before some, especially those within the northern latitudes of their historic range, swim back to the ocean to repeat their spawning migrations over the next several years.12 Before the construction of large dams on the Merrimack River, shad traveled as far as north as Lake Winnipesaukee, an astounding 125 miles from the coast, allowing inhabitants of the entire Merrimack River valley an opportunity to take advantage of this seasonal resource. As the shad move deep into the interior they pass into smaller tributaries, seeking larger and warmer bodies of water to spawn. Fishermen took shad with weirs, seines, and drift nets in lower reaches of a river but also used boats, seines, and dip nets close to waterfalls and other natural obstacles. New England’s rural communities came to depend on the annual shad runs as an important article of their household subsistence, but early nineteenth-century commercial shad fishermen put significant pressure on this particular species. The Connecticut River, home to what was once one of the most abundant shad fisheries in New England, increasingly attracted a class of full-time commercial fishermen, particularly within the estuary. Beginning around 1849, fishermen built pound nets, a fixed equipment similar to weirs, that crowded the mouth of the river near Long Island Sound and hijacked entire schools of shad. Between 1866 and 1871, a single pound net in Westbrook, Connecticut, captured over ten thousand shad each year.13 Juvenile shad also historically served an important function within the marine food chain, luring deep-sea fish such as haddock and cod to coastal waters. The downriver migrations of juvenile rainbow smelt, alewives, and shad toward coastal waters connected freshwater and marine ecosystems and contributed to productive inshore fisheries.14

The Atlantic salmon’s habitat once stretched from as far north as Canada’s Atlantic provinces and then south to the Housatonic River in Connecticut. One of the longest anadromous migrations in terms of duration, Atlantic salmon leave the ocean at various points throughout the spring, summer, and early fall.15 Famous for their feats of athleticism, salmon leap incredible distances over seemingly insurmountable obstacles to reach upland spawning grounds. Appropriately, the latter portion of the Latin name, Salmo salar, translates as “the leaper.” Though the Connecticut and the Merrimack Rivers once hosted large populations of this anadromous species, the state of Maine laid claim to the most abundant Atlantic salmon fisheries in the northeast. The Indigenous Wabanaki peoples fished deep pools from their canoes with torches and spears. When the soils failed to accommodate productive farms, rural fishermen on the coast of Maine depended on inshore and river fishing to eke out a living. This species also attracted commercial pressure, with fishermen employing both mobile and fixed gear, including drift nets, pound nets, weirs, and seines. Starting in the 1820s, merchants sent schooners up the Atlantic coast to the Penobscot River to purchase barrels of cured salmon for markets in Boston and New York.16 In addition to impacts from commercial overfishing, salmon suffered the most from callous obstruction of upland spawning habitat.

Unfortunately, because Atlantic salmon require access to the entire watershed to complete their life cycle and spawn the next generation, this species was uniquely vulnerable to human interference. According to fisheries biologists, environmental conditions must permit “unobstructed access between freshwater, estuarine, and marine environments. In these variable ecosystems, an intricate set of events is required for salmon to successfully complete their life cycle.”17 Before the construction of large industrial dams in the nineteenth century, salmon migrations extended deep into the upland headwaters of the region’s largest river systems, which afforded rural farmer-fishermen opportunities to access these seasonal fish runs. Prior to the 1820s, which saw the factory town of Lowell, Massachusetts, emerge as the paradigm of industrial manufacturing, both salmon and shad ascended the Merrimack River to Franklin, New Hampshire, at which point the salmon followed the Pemigewasset River toward the cold streams of the White Mountains.18 Atlantic salmon thrive in cold-water environments. The colder the water, the greater the concentration of dissolved oxygen, which is necessary to sustain anadromous species like Atlantic salmon. Within these mountain streams, between October and November, female salmon bury their eggs in gravel river bottoms, which offer some protection against predators; the eggs hatch the following spring.19 These young salmon, called “parr,” typically remain in headwater streams for as long as six years until they undergo a host of physiological, hormonal, and behavioral changes that prepare them for their ocean journey. Now classified as smolts, they finally resemble the silvery adults they will soon join in the sea. After a two-year journey across thousands of miles of open ocean—intermingling with other salmon from Canada, Greenland, Iceland, and Europe—Atlantic salmon return from feeding grounds in the Labrador Sea as adults weighing upward of ten pounds. Unlike their Pacific relatives, Atlantic salmon may repeat this cycle more than once.20 Once abundant in large and small river systems across the Northeast, the salmon’s historic habitat has shrunk to only a few rivers in Maine, and even in those remaining few the federal government lists them as an endangered species. For this reason, mid-nineteenth-century state fish commissions and, more recently, environmental organizations have expended significant time and resources to restore Atlantic salmon to their native waters.

Every spring and summer, New England’s rivers were once filled with incr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Notes

- Index