eBook - ePub

Revolutions at Home

The Origin of Modern Childhood and the German Middle Class

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Revolutions at Home

The Origin of Modern Childhood and the German Middle Class

About this book

How did we come to imagine what "ideal childhood" requires? Beginning in the late eighteenth century, German child-rearing radically transformed, and as these innovations in ideology and educational practice spread from middle-class families across European society, childhood came to be seen as a life stage critical to self-formation. This new approach was in part a process that adults imposed on youth, one that hinged on motivating children's behavior through affection and cultivating internal discipline. But this is not just a story about parents' and pedagogues' efforts to shape childhood. Offering rare glimpses of young students' diaries, letters, and marginalia, Emily C. Bruce reveals how children themselves negotiated these changes.

Revolutions at Home analyzes a rich set of documents created for and by young Germans to show that children were central to reinventing their own education between 1770 and 1850. Through their reading and writing, they helped construct the modern child subject. The active child who emerged at this time was not simply a consequence of expanding literacy but, in fact, a key participant in defining modern life.

Revolutions at Home analyzes a rich set of documents created for and by young Germans to show that children were central to reinventing their own education between 1770 and 1850. Through their reading and writing, they helped construct the modern child subject. The active child who emerged at this time was not simply a consequence of expanding literacy but, in fact, a key participant in defining modern life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Revolutions at Home by Emily C. Bruce,Emily Bruce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Massachusetts PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9781625345622, 9781625345639eBook ISBN

9781613768150Chapter One

Reading Serially

The New Enlightenment Youth

Periodical for the New Youth Subject

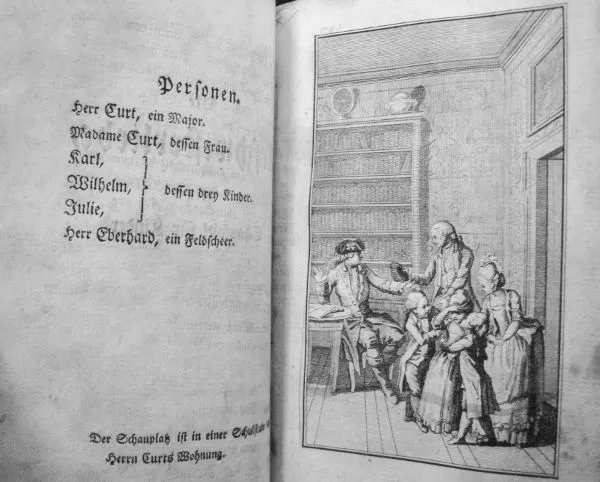

Opening the first issue in April 1776 of a popular weekly magazine by Christian Felix Weiße, young readers found a dialogue in seven scenes. The story went like this: While playing with his father’s gun, Karl accidentally shot his little sister, Julie. Seeing her covered in blood, their brother Wilhelm cried out that he would give his own life for her, and Karl fell in a swoon. Their father demanded to know who was responsible. His rage was so terrifying, the brothers covered for one another to prevent a second murder! Then—Julie miraculously revived, claiming responsibility for shooting herself and refusing to let Karl be punished. Moved by the children’s loving defense of one another, their father relented, grateful to his mendacious children for preventing him from shooting the culprit.

One could be distracted by this story’s shocking content, or read it as an Age of Revolutions anti-authoritarian allegory. But the uses of this little soap opera as a pedagogic tool are particularly intriguing. Imagine the German children who subscribed to Der Kinderfreund: Ein Wochenblatt für Kinder (The Children’s Friend: A Weekly for Children) in the 1770s and 1780s. What can we surmise about how they responded to “Sibling Love”? Did they recognize characters from previous serials? Who laughed through the silly opening scene of Wilhelm’s arithmetic mistakes? Who skipped ahead for the fun of rehearsing the dramatic gunshot itself? What pleasure did child readers find in the vivid, over-the-top stage directions? If a set of siblings performed this dialogue, did someone want to play the terrifying father? What happened when girls read parts written for boys, and vice versa? Who claimed the position of director?

FIGURE 3. Cast list and facing illustration of “Sibling Love” from Christian Felix Weiße, Der Kinderfreund, 1776. Kinder- und Jugendbuchabteilung, Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

Various sources furnish evidence of reading practices around dialogues such as this one. Family archives document that elite German children often copied, wrote, and performed plays with siblings, parents, and tutors. Folklorists, child development researchers, and our own experiences as children tell us that performance and storytelling of some kind are ubiquitous in growing up. The genre of sentimental drama would have been familiar to eighteenth-century child readers, given its frequent appearance in youth periodicals. We can suppose that siblings receiving Der Kinderfreund read this play together even if they did not act it out, since the magazine’s subscription list included girls and boys in a wide range of ages. But perhaps most suggestive for considering child readers’ practices is what follows after the play: a moral lesson placed in a more realistic setting. The coda suggests that children should apply similar principles to the scenario of a brother lying for his sister after she breaks two porcelain cups.

The play and its framing story point toward the same moral guidance: prioritizing compassion for the feelings of others, even if that suffering is caused by a parent’s discipline. Beyond that, the lesson also models a way to read, with fictional children from the frame narrative discussing the story they have just heard with their father, identifying personally with its characters, and investing it with meaning for their quotidian life. This new genre of youth periodicals invited children to play an active, imaginative role in their reading, for an education that was more sentimental and concerned with children’s amusement than ever before.

In this chapter, I explore how Enlightenment youth periodicals supported the development of the modern child subject. The commercial expansion of a new genre during the years around 1800 provided a literary laboratory for pedagogic ideas about children’s innocence and the cultivation of self-control; at the same time, the growing success of these publications indicated the reimagination of child readers as a distinct audience. Forms such as dialogues for children’s performance and serialized tales both scripted and responded to changing reading practices. While the texts provide direct evidence of adult values about childhood, children’s tastes and changing uses of periodicals influenced the development of a modern children’s literature. The stories themselves depicted ideal readers and sentimental family life in line with the new ideology of childhood, but were also subject to a range of possible readings and misreadings. Enlightenment periodicals especially contributed to the emergence of a new kind of reader through the fashioning of gendered subjectivities in texts directed both at girls and at a cross-gender audience. Not only did adults’ desire “to amuse and instruct” signal greater attention to child readers’ desires and agency, but the spread of such texts offered more opportunities for children themselves to negotiate their reading education.

More than sixty titles published between 1756 and 1855 are surveyed in this chapter, as the publication of youth periodicals exploded at the end of the eighteenth century. After taking a look at the forms and stories found in these texts—that is, how they were written and what they were written about—I examine the construction of gendered subjectivities in periodicals as a crucial dimension of young people’s changing reading practices. Throughout, I indicate ways of thinking about child readers’ reception and practices around the developing genre of youth periodicals.

Genre Development

In their style and format, youth periodicals of the European Enlightenment owed a debt to the moral weeklies that, building on an English tradition, had been published for adults since the early eighteenth century.1 The 1770s and 1780s witnessed an explosion of magazines, weeklies, yearbooks, almanacs, and other serialized readers especially redesigned for children and youth.2 I suggest that the swift adoption of periodicals by pedagogues demonstrates a growing preoccupation with children’s literacy practices as a cornerstone of constructing the modern child subject.3 Pedagogic use of serial publications also underscored this era’s reimagination of childhood as a separate stage of life that required its own books. Periodicals quickly generated new texts that could guide child readers to moral action and emotional expression. These publications also carried the pedagogic aims of the Enlightenment into the home.

Typical Characteristics

The definition of a youth periodical during the years around 1800 was not narrowly fixed. Some periodicals were very short-lived and some single books were so frequently updated in subsequent editions that they functioned in ways similar to magazines and yearbooks. For example, Nadine Bérenguier describes Madame Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s influential Magasin des enfans (Children’s Storehouse, first published in 1756) as a conduct book, which it certainly was in its moralizing content. The French word magasin meant then more a warehouse or treasury than did its later cognate, magazine. But this sense of collecting and anthologizing material over time was reflected in Leprince de Beaumont’s search for future subscribers and promise to issue future annual volumes. In this way, it was a foundational model for many later periodicals and children’s books from German, French, British, and American publishers. I suggest that we should attend both to the form of such a text and to its function in children’s education.

Beyond these variations, what did a typical Enlightenment youth periodical look like? (See Appendix A for the tables of contents from two exemplary publications.) Some form of serialization was key, though I have included titles that were published as frequently as twice weekly and as infrequently as annual yearbooks. Some only survived about a year, but longevity increased moving into the nineteenth century.4 A few titles introduced at the end of the period under examination here lasted in some form into the early twentieth century. Most Enlightenment-era magazines and weeklies had short runs, but surprisingly wide distribution. Some were short-lived because their creators moved on to other projects but did become more popular from year to year.5 The volumes were usually small—often pocket-sized—and ranged in the quality of their paper, printing, and presentation. As with fairy tales and schoolbooks, technological innovations throughout this period increased the number and interest level of accompanying illustrations. Some included fold-out copies of sheet music for folk and art songs, supporting their cultivation of bourgeois arts. Many of the earlier periodicals still followed the old practice of an opening letter of dedication to a royal patron.

Authors and Readers

Authors of youth periodicals, both men and women, often asserted their natural authority as teachers or parents in order to connect with the child reader audience.6 For example, Leprince de Beaumont’s time as a governess in England prompted her to write the Magasin des enfans. She explicitly offered this experience as evidence of her knowledge of children and as a moral authority on their education. Meanwhile, Weiße painted a picture of his narrator surrogate in the first issue of Der Kinderfreund as a self-sacrificing father whose only pleasure in life was his children.7 Writing on the use of this same device by French conduct-book authors, Bérenguier calls it “the Crucial Role of Experience.”8 Bérenguier perhaps takes these claimed biographies too much at face value, since authors were often performing fictional parental roles; nevertheless, some previous connection to children’s education was a common background for the women and men of letters who turned to producing amusing periodicals in their pursuit of a youth audience.

While some of the periodicals I have examined were explicitly aimed at young children below the age of ten, in many cases the imagined audience of these periodicals was older. However, age is one of several boundaries of publishers’ intended audience that was permeable in practice. This can be seen in the subscribers’ list published in the Niedersächsisches Wochenblatt für Kinder (Lower Saxony Weekly for Children, orig. 1774) in its 1781 and 1783 volumes. Families of four or five children each were listed by name, spanning enough years to suggest that youth were reading before or beyond the intended age.

Subscriptions

Young readers acquired periodicals in a number of ways, including at shops and book fairs. One early magazine explained in each issue the ideal methods of finding the Leipziger Wochenblatt für Kinder (Leipzig Weekly for Children, 1772–74):

In the coming new year, this weekly paper will still be issued on the usual days, namely Mondays and Thursdays, both at the local newspaper stall as well as in the Crusius bookshop in Paulino. Elsewhere it is to be had both at any post office and in the principal bookstores.

The frequent publication of this title is worth noting, as is the range of distribution sites beyond the publisher’s main shop. A later volume noted that supplementary materials (a collection of letters by the fictional child protagonists of the weekly stories) were being sold to benefit educational institutions in the Ore Mountains of Saxony.9

Eighteenth-century European publishing was often financed by reader subscriptions. In a quintessentially modern turn to middle-class consumers versus a single aristocratic patron, subscriptions were collected by publishers from across wide regions. Serial publications were especially suited to the subscription process, since readers could invest in a title and continue to receive new volumes over time.10 The first edition of Leprince de Beaumont’s Magasin des enfans warned readers “who wish the continuation of this Magasin that it cannot be printed, unless we are sure of one hundred subscriptions; they are therefore urged to subscribe early.”11 In that case, they exceeded their initial modest hopes, and continued to issue new volumes. To encourage subscriptions, publishers offered special deals, as when the first volume of Für deutsche Mädchen (For German Girls, 1781–82) noted that subscribers would receive the next volume at their known address for the special rate of four issues at three guilders.12 The editor Paul Nitsch wrote “with prophetic spirit” that he would like to begin with at least a couple hundred “admirable girls” as readers.13 Aimed at younger girls, this publication was very regularly printed, missing only one week during Christmas. Even though it was short-lived in its original run, it was popular enough to be collected and reprinted some years later. In fact, many of these periodicals, especially in the eighteenth century, were gathered and reissued in bound volumes.

Even where a list of subscribers seems small to us today, it could be of great value in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century book trade. When publisher Johann Friedrich Cotta and author Marianne Ehrmann had a famous falling out over the popular girls’ periodical Flora, Ehrmann created a new journal but Cotta had possession of the original subscription list and was able to continue sending out magazines under the cover of the old title.14 Subscription proved a useful tool for the cultivation of a community of youth readers. The explosion of the genre was not possible without the financial and cultural investment of German families.

Foundational Titles

Several titles from the late Enlightenment stood out as especially successful or influential for the development of youth periodicals and children’s literature extending into the nineteenth century. They also furthered the construction of a modern child subject through their establishment of normative practices for children’s reading and propagation of ideas about children’s interiority. These landmarks include some publications already mentioned: Madame Leprince de Beaumont’s Magasin des enfans (first published 1756) and its German translation (first published 1761), Johann Christian Adelung’s Leipziger...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Conclusion

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index