- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

State of the World 2000 shines a sharp light on the great challenge our civilization faces: how to use our political systems to manage the difficult and complex relationships between the global economy and the Earth's ecosystems. If we cannot build an environmentally sustainable global economy, then we have no future that anyone would desire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access State of the World 2000 by The Worldwatch Institute in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Island PressYear

2015eBook ISBN

9781610916394Subtopic

Environment & Energy PolicyChapter 1

Challenges of the New Century

Lester R. Brown

As we look back at the many spectacular achievements of the century just ended, the landing on the Moon in July 1969 by American astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stands out. At the beginning of the century, few could imagine humans flying, much less breaking out of Earth’s field of gravity to journey to the Moon. And few could imagine how quickly the world would go from air travel to space exploration.

Indeed, when the century began, the Wright brothers were still working in their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, trying to design a craft that would fly. Just 66 years elapsed from their first precarious flight in 1903 on the beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to the landing on the Moon. Although their first flight was only 120 feet, it opened a new era, setting the stage for a century of breathtaking advances in technology.1

In 1945, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering successfully designed what many consider to be the first electronic computer, the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer). This advance was to have an even more pervasive effect than the Wright brothers’ invention, as it set the stage for the evolution of the information economy. Computer technology progressed even more rapidly, going from the era of large mainframes to personal computers in just a few decades.2

A new industry evolved. New firms were created. IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Dell, Apple, Microsoft, Intel, and America On-Line became household names. Fortunes were made overnight. When the listed stock value of Microsoft overtook that of General Motors in 1998, it marked the beginning of a new era—a shift from a period dominated by heavy industry to one dominated by information.3

The stage was set for the evolution of the Internet, a novel concept that has tied the world together as never before. Although still in its early stages as the new century begins, the Internet is already affecting virtually every facet of our lives—changing communication, commerce, work, education, and entertainment. It is creating a new culture, one that is evolving in cyberspace.

Some 23 million Africans are beginning a new century with a death sentence imposed by HIV.

In the United States, the information technology industry, including computer and communications hardware, software, and the provision of related services, was a major source of economic growth during the 1990s. Creating millions of new, higher paying jobs, it has helped fuel the longest peacetime economic expansion in history. It has also induced a certain economic euphoria, one that helped drive the Dow Jones Industrial Average of stock prices to a long string of successive highs, raising it from less than 3,000 in early 1990 to over 11,000 in 1999.4

Caught up in this economic excitement, we seem to have lost sight of the deterioration of environmental systems and resources. The contrast between our bright hopes for the future of the information economy and the deterioration of Earth’s ecosystem leaves us with a schizophrenic outlook.

Although the contrast between our civilization and that of our hunter-gatherer ancestors could scarcely be greater, we do have one thing in common—we, too, depend entirely on Earth’s natural systems and resources to sustain us. Unfortunately, the expanding global economy that is driving the Dow Jones to new highs is, as currently structured, outgrowing those ecosystems. Evidence of this can be seen in shrinking forests, eroding soils, falling water tables, collapsing fisheries, rising temperatures, dying coral reefs, melting glaciers, and disappearing plant and animal species.

As pressures mount with each passing year, more local ecosystems collapse. Soil erosion has forced Kazakhstan, for instance, to abandon half its cropland since 1980. The Atlantic swordfish fishery is on the verge of collapsing. The Aral Sea, producing over 40 million kilograms of fish a year as recently as 1960, is now dead. The Philippines and Côte d’Ivoire have lost their thriving forest product export industries because their once luxuriant stands of tropical hardwoods are largely gone. The rich oyster beds of the Chesapeake Bay that yielded more than 70 million kilograms a year in the early twentieth century produced less than 2 million kilograms in 1998. As the global economy expands, local ecosystems are collapsing at an accelerating pace.5

Even as the Dow Jones climbed to new highs during the 1990s, ecologists were noting that ever growing human demands would eventually lead to local breakdowns, a situation where deterioration would replace progress. No one knew what form this would take, whether it would be water shortages, food shortages, disease, internal ethnic conflict, or external political conflict.

The first region where decline is replacing progress is sub-Saharan Africa. In this region of 800 million people, life expectancy—a sentinel indicator of progress—is falling precipitously as governments overwhelmed by rapid population growth have failed to curb the spread of the virus that leads to AIDS. In several countries, more than 20 percent of adults are infected with HIV. Barring a medical miracle, these countries will lose one fifth or more of their adult population during this decade. In the absence of a low-cost cure, some 23 million Africans are beginning a new century with a death sentence imposed by the virus. With the failure of governments in the region to control the spread of HIV, it is becoming an epidemic of epic proportions. It is also a tragedy of epic proportions.6

Unfortunately, other trends also have the potential of reducing life expectancy in the years ahead, of turning back the clock of economic progress. In India, for instance, water pumped from underground far exceeds aquifer recharge. The resulting fall in water tables will eventually lead to a steep cutback in irrigation water supplies, threatening to reduce food production. Unless New Delhi can quickly devise an effective strategy to deal with spreading water scarcity, India—like Africa—may soon face a decline in life expectancy.7

Environmental Trends Shaping the New Century

As the twenty-first century begins, several well-established environmental trends are shaping the future of civilization. This section discusses seven of these: population growth, rising temperature, falling water tables, shrinking cropland per person, collapsing fisheries, shrinking forests, and the loss of plant and animal species.

The projected growth in population over the next half-century may more directly affect economic progress than any other single trend, exacerbating nearly all other environmental and social problems. Between 1950 and 2000, world population increased from 2.5 billion to 6.1 billion, a gain of 3.6 billion. And even though birth rates have fallen in most of the world, recent projections show that population is projected to grow to 8.9 billion by 2050, a gain of 2.8 billion. Whereas past growth occurred in both industrial and developing countries, virtually all future growth will occur in the developing world, where countries are already overpopulated, according to many ecological measures. Where population is projected to double or even triple during this century, countries face even more growth in the future than in the past.8

Our numbers continue to expand, but Earth’s natural systems do not. The amount of fresh water produced by the hydrological cycle is essentially the same today as it was in 1950 and as it is likely to be in 2050. So, too, is the sustainable yield of oceanic fisheries, of forests, and of rangelands. As population grows, the shrinking per capita supply of each of these natural resources threatens not only the quality of life but, in some situations, even life itself.

A second trend that is affecting the entire world is the rise in temperature that results from increasing atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2). When the Industrial Revolution began more than two centuries ago, the CO2 concentration was estimated at 280 parts per million (ppm). By 1959, when detailed measurements began, using modern instruments, the CO2 level was 316 ppm, a rise of 13 percent over two centuries. By 1998, it had reached 367 ppm, climbing 17 percent in just 39 years. This increase has become one of Earth’s most predictable environmental trends.9

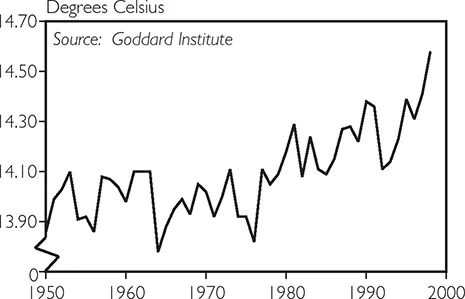

Global average temperature has also risen, especially during the last three decades—the period when CO2 levels have been rising most rapidly. The average global temperature for 1969–71 was 13.99 degrees Celsius. By 1996–98, it was 14.43 degrees, a gain of 0.44 Celsius (0.8 degrees Fahrenheit). (See Figure 1–1.)10

If CO2 concentrations double pre-industrial levels during this century, as projected, global temperature is likely to rise by at least 1 degree Celsius and perhaps as much as 4 degrees (2–7 degrees Fahrenheit). Meanwhile, sea level is projected to rise from a minimum of 17 centimeters to as much as 1 meter by 2100.11

Figure 1–1. Average Temperature at Earth’s Surface, 1950–98

This will alter every ecosystem on Earth. Already, coral reefs are being affected in nearly all the world’s oceans, including the rich concentrations of reefs in the vast eastern Pacific and in the Indian Ocean, stretching from the east coast of Africa to the Indian subcontinent. For example, record sea surface temperatures over the last two years may have wiped out 70 percent of the coral in the Indian Ocean. (See Chapter 2.) Coral reefs, complex ecosystems that are sometimes referred to as the rainforests of the sea, not only serve as breeding grounds for many species of marine life, they also protect coastlines from storms and storm surges.12

The modest temperature rise in recent decades is melting ice caps and glaciers. Ice cover is shrinking in the Arctic, the Antarctic, Alaska, Greenland, the Alps, the Andes, and the Quinghai-Tibetan Plateau. A team of U.S. and British scientists reported in mid-1999 that the two ice shelves on either side of the Antarctic peninsula are in full retreat. Over roughly a half-century through 1997, they lost 7,000 square kilometers. But then within a year or so they lost 3,000 square kilometers. The scientists attribute the accelerated ice melting to a regional rise in average temperature of some 2.5 degrees Celsius (4.5 degrees Fahrenheit) since 1940.13

In the fall of 1991, hikers in the southwestern Alps near the border of Austria and Italy discovered an intact human body, a male, protruding from a glacier. Believed to have been trapped in a storm some 5,000 years ago and quickly covered with snow and ice, his body was remarkably well preserved. And in the late summer of 1999, another body was found protruding from a melting glacier in the Yukon territory of western Canada. Our ancestors are emerging from the ice with a message for us: Earth is getting warmer.14

One of the least visible trends that is shaping our future is falling water tables. Although irrigation problems, such as waterlogging, salting, and silting, go back several thousand years, aquifer depletion is a new one, confined largely to the last half-century, when powerful diesel and electric pumps made it possible to extract underground water at rates that exceed the natural recharge from rainfall and melting snow. According to Sandra Postel of the Global Water Policy Project, overpumping of aquifers in China, India, North Africa, Saudi Arabia, and the United States exceeds 160 billion tons of water per year. Since it takes roughly 1,000 tons of water to produce 1 ton of grain, this is the equivalent of 160 million tons of grain, or half the U.S. grain harvest. In consumption terms, the food supply of 480 million of the world’s 6 billion people is being produced with the unsustainable use of water.15

The largest single deficits are in India and China. As India’s population has tripled since 1950, water demand has climbed to where it may now be double the sustainable yield of the country’s aquifers. As a result, water tables are falling in much of the country and wells are running dry in thousands of villages. The International Water Management Institute, the world’s premier water research body, estimates that aquifer depletion and the resulting cutbacks in irrigation water could drop India’s grain harvest by up to one fourth. In a country that is adding 18 million people a year and where more than half of all children are malnourished and underweight, a shrinking harvest could increase hunger-related deaths, adding to the 6 million worldwide who die each year from hunger and malnutrition.16

In China, the quadrupling of the economy since 1980 has raised water use far beyond the sustainable yield of aquifer recharge. The result is that water tables are falling virtually everywhere the land is flat. Under the north China plain, which produces 40 percent of the country’s grain harvest, the water table is falling by 1.6 meters (5 feet) a year. As aquifer depletion and the diversion of water to cities shrink irrigation water supplies, China may be forced to import grain on a scale that could destabilize world grain markets.17

Also making it more difficult to feed the projected growth in population adequately over the next few decades is the worldwide shrinkage in cropland per person. Since the mid-twentieth century, grainland area per person has fallen in half, from 0.24 hectares to 0.12 hectares. If the world grain area remains more or less constant over the next half-century (assuming that cropland expansion in such areas as Brazil’s cerrado will offset the worldwide losses of cropland to urbanization, industrialization...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 1: Challenges of the New Century

- Chapter 2: Anticipating Environmental “Surprise”

- Chapter 3: Redesigning Irrigated Agriculture

- Chapter 4: Nourishing the Underfed and Overfed

- Chapter 5: Phasing Out Persistent Organic Pollutants

- Chapter 6: Recovering the Paper Landscape

- Chapter 7: Harnessing Information Technologies for the Environment

- Chapter 8: Sizing Up Micropower

- Chapter 9: Creating Jobs, Preserving the Environment

- Chapter 10: Coping with Ecological Globalization

- Notes

- The acclaimed series from Worldwatch Institute

- You Can Make a Difference