![]()

[ONE]

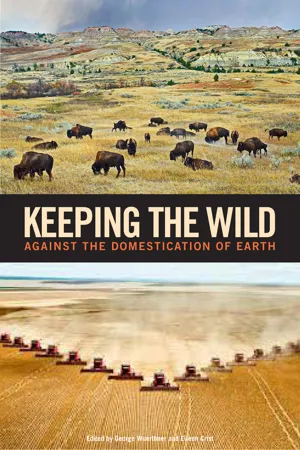

CLASHING WORLDVIEWS

![]()

Rise of the Neo-greens

PAUL KINGSNORTH

I HAVE BEEN (AND STILL AM) someone rather often quaintly known as a “green activist” for around twenty years now: for a lot longer than some people, and for a lot less time than many others. I sometimes like to say that the green movement was born in the same year as me—1972, the year in which the fabled Limits to Growth report was published by the Club of Rome—and this is near enough to the truth to be a jumping-off point for a narrative.

If the green movement was born in the early 1970s, then the 1980s, when there were whales to be saved and rainforests to campaign for, were its adolescence. Its coming-of-age party was in 1992, in the Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro. The 1992 Earth Summit was a jamboree of promises and commitments: to tackle climate change, to protect forests, to protect biodiversity, and to promote something called “sustainable development,” a new concept which would become, over the next two decades, the most fashionable in global politics and business. The future looked bright for the greens back then. It often does when you’re twenty.

Two decades on, things look rather different. In 2012, the bureaucrats, the activists, and the ministers gathered again in Rio for a stock-taking exercise called “Rio +20.” It was accompanied by the usual shrill demands for optimism and hope, but there was no disguising the hollowness of the exercise. Every environmental problem identified at the original Earth Summit has got worse in the intervening twenty years, often very much worse, and there is no sign of this changing.

The green movement, which seemed to be carrying all before it in the early 1990s, has plunged into a full-on midlife crisis. Unable to significantly change either the system or the behavior of the public, assailed by a rising movement of “skeptics” and by public boredom with being hectored about carbon and consumption, colonized by a new breed of corporate spivs for whom “sustainability” is just another opportunity for selling things, the greens are seeing a nasty realization dawn: Despite all their work, their passion, their commitment, and the fact that most of what they have been saying has been broadly right—they are losing. There is no likelihood of the world going their way. In most green circles now, sooner or later, the conversation comes round to the same question: What the hell do we do next?

There are plenty of people who think they know the answer to that question. One of them is Peter Kareiva, who would like to think that he and his kind represent the future of environmentalism, and who may turn out to be right. Kareiva is chief scientist of the Nature Conservancy, an American nongovernmental organization (NGO) which claims to be the world’s largest environmental organization. He is a scientist, a revisionist, and one among a growing number of former greens who might best be called “neoenvironmentalists.”

The resemblance between this coalescing group and the Friedmanite neoliberals of the early 1970s is intriguing. Like the neoliberals, the neoenvironmentalists are attempting to break through the lines of an old orthodoxy which is visibly exhausted and confused. Like the neoliberals, they are mostly American and mostly male, and they emphasize scientific measurement and economic analysis over other ways of seeing and measuring. Like the neoliberals, their tendency is to cluster around a few key think tanks: back then, the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Cato Institute, and the Adam Smith Institute; now, the Breakthrough Institute, the Long Now Foundation, and the Copenhagen Consensus. Like the neoliberals, they are beginning to grow in numbers at a time of global collapse and uncertainty. And like the neoliberals, they think they have radical solutions.

Kareiva’s ideas are a good place to start in understanding them. He is a prominent conservation scientist who believes that most of what the greens think they know is wrong. Nature, he says, is more resilient than fragile; science proves it. “Humans degrade and destroy and crucify the natural environment,” he writes, “and 80 percent of the time it recovers pretty well.”1 Wilderness does not exist; all of it has been influenced by humans at some time. Trying to protect large functioning ecosystems from human development is mostly futile; humans like development, and you can’t stop them having it. Nature is tough and will adapt to this: “Today, coyotes roam downtown Chicago and peregrines astonish San Franciscans as they sweep down skyscraper canyons. . . . [A]s we destroy habitats, we create new ones.”2

Now that “science” has shown us that nothing is “pristine” and nature “adapts,” there’s no reason to worry about many traditional green goals such as protecting rainforest habitats. “Is halting deforestation in the Amazon . . . feasible?” Kareiva and colleagues ask, “Is it even necessary?”3 Somehow, you know what the answer is going to be before the authors give it to you.

If this sounds like the kind of thing that a U.S. Republican presidential candidate might come out with, that’s because it is. But Kareiva and colleagues are not alone. Variations on this line have recently been pushed by the U.S. thinker Stewart Brand; the British writer Mark Lynas; the Danish anti-green poster boy Bjørn Lomborg; and the American writers Emma Marris, Ted Nordhaus, and Michael Shellenberger. They in turn are building on work done in the past by other self-declared green “heretics” like Richard D. North, Brian Clegg, and Wilfred Beckerman.

Beyond the field of conservation, the neoenvironmentalists are distinguished by their attitude toward new technologies, which they almost uniformly see as positive. Civilization, nature, and people can be “saved” only by enthusiastically embracing biotechnology, synthetic biology, nuclear power, geoengineering, and anything else with the prefix “new” that annoys Greenpeace. The traditional green focus on limits is dismissed as naive. We are now, in Brand’s words, “as Gods,” and we have to step up and accept our responsibility to manage the planet rationally through the use of new technology guided by enlightened science.

Neo-environmentalists also tend to exhibit an excitable enthusiasm for markets. They like to put a price on things like trees, lakes, mist, crocodiles, rainforests, and watersheds, all of which can deliver “ecosystem services” which can be bought and sold, measured and totted up. Tied in with this is an almost religious attitude toward the scientific method. Everything that matters can be measured by science and priced by markets, and any claims without numbers attached can be easily dismissed. This is presented as “pragmatism” but is actually something rather different: an attempt to exclude from the green debate any interventions based on morality, emotion, intuition, spiritual connection, or simple human feeling.

Some of this might be shocking to some old-guard greens—which is the point, but it is hardly a new message. In fact, it is a very old one; it is simply a variant on the old Wellsian techno-optimism which has been promising us cornucopia for over a century. It’s an old-fashioned Big Science, Big Tech, and Big Money narrative, filtered through the lens of the Internet and garlanded with holier-than-thou talk about saving the poor and feeding the world.

But though they burn with the shouty fervor of the born-again, the neoenvironmentalists are not exactly wrong. In fact, they are at least half right. They are right to say that the human-scale, convivial approaches of many of the original green thinkers are never going to work if the world continues to formulate itself according to the demands of late capitalist industrialism. They are right to say that a world of 9 billion people all seeking the status of middle-class consumers cannot be sustained by vernacular approaches. They are right to say that the human impact on the planet is enormous and irreversible. They are right to say that traditional conservation efforts sometimes idealize a preindustrial nature. They are right to say that the campaigns of green NGOs often exaggerate and dissemble. And they are right to say that the greens have hit a wall, and that continuing to ram their heads against it is not going to knock it down.

What’s interesting, though, is what they go on to build on this foundation. The first sign that this is not, as declared, a simple “ecopragmatism,” but is something rather different, comes when you read statements like this:

For decades people have unquestioningly accepted the idea that our goal is to preserve nature in its pristine, prehuman state. But many scientists have come to see this as an outdated dream that thwarts bold new plans to save the environment and prevents us from having a fuller relationship with nature.4

This passage appears on author Emma Marris’s website, in connection with her book Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World,5 though it could just as easily be from anywhere else in the neoenvironmentalist canon. But who are the many “people” who have “unquestioningly accepted” this line? I’ve met a lot of conservationists and environmentalists in my time, and I don’t think I’ve ever met one who believed there was any such thing as “pristine, prehuman” nature. What they did believe was that there were still large-scale, functioning ecosystems which were worth getting out of bed for to help protect them from destruction.

To understand why, consider the case of the Amazon. What do we value about the Amazon forest? Do people seek to protect it because they believe it is “pristine” and “prehuman”? Clearly not, since it’s inhabited and harvested by large numbers of tribal people, some of whom have been there for millennia. The Amazon is not important because it is untouched; it’s important because it is wild, in the sense that it is self-willed. Humans live in and from it, but it is not created or controlled by them. It teems with a great, shifting, complex diversity of both human and nonhuman life, and no species dominates the mix. It is a complex, working ecosystem which is also a human-culture system, because in any kind of worthwhile world, the two are linked.

This is what intelligent green thinking has always called for: human and nonhuman nature working in some degree of harmony, in a modern world of compromise and change in which some principles, nevertheless, are worth cleaving to. Nature is a resource for people, and always has been; we all have to eat, make shelter, hunt, and live from its bounty like any other creature. But that doesn’t preclude our understanding that it has a practical, cultural, emotional, and even spiritual value beyond that too, which is equally necessary for our well-being.

The neoenvironmentalists, needless to say, have no time for this kind of fluff. They have a great big straw man to build up and knock down, and once they’ve got that out of the way, they can move on to the really important part of their message. Here’s Kareiva, with fellow authors Robert Lalasz and Michelle Marvier, giving us the money shot in their Breakthrough Journal article:

Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of people. . . . Conservation will measure its achievement in large part by its relevance to people.6

There it is, in black and white: The wild is dead, and what remains of nature is for people. We can effectively do what we like, and we should. Science says so! A full circle has been drawn, the greens have been buried by their own children, and under the soil with them has gone their naive, romantic, and antiscientific belief that nonhuman life has any value beyond what we very modern humans can make use of.

During my twenty years in the green movement, I’ve got a good feel for the many fault lines, divisions, debates, and arguments with which that movement, like any other, is riven. But to me, this feels like something different. The rise of the neogreens feels like not simply another internal argument but an entirely new sloughing-off of some key green principles. It seems like a bunch of people keen to continue to define themselves as radicals, and as environmentalists, while acting and talking in a way that makes it clear that they are precisely the opposite.

The neogreens do not come to rejuvenate environmentalism; they come to bury it. They come to tell us that nature doesn’t matter; that there is no such thing as nature anyway; that the interests of human beings should always be paramount; that the rational mind must always win out over the intuitive mind; and that the political and economic settlement we have come to know in the last twenty years as “globalization” is the only game in town, now and probably forever. All of the questions the greens have been raising for decades about the meaning of progress, about how we should live in relationship to other species, and about technology and political organization and human-scale development are to be thrown in the bin like children’s toys.

Over the next few years, the old green movement that I grew up with is likely to fall to pieces. Many of those pieces will be picked up and hoarded by the growing ranks of the neoenvironmentalists. The mainstream of the green movement has laid itself open to their advances in recent years with its obsessive focus on carbon and energy technologies and its refusal to speak up for a subjective, vernacular, nontechnical engagement with nature. The neoenvironmentalists have a great advantage over the old greens, with their threatening talk about limits to growth, behavior change, and other such against-the-grain stuff: They are telling this civilization what it wants to hear.

In the short term, the future belongs to the neoenvironmentalists, and it is going to be painful to watch. In the long term, though, I suspect they will fail, for two reasons. Firstly, bubbles always burst. Our civilization is beginning to break down. We are at the start of an unfolding economic and social collapse which may take decades or longer to play out—and which is playing out against the background of a planetary ecocide that nobody seems able to prevent. We are not gods, and our machines will not get us off this hook, however clever they are and however much we would like to believe it.

But there is another reason that the new breed are unlikely to be able to build the world they want to see: We are not—even they are not—primarily rational, logical, or “scientific” beings. Our human relationship to the rest of nature is not akin to the analysis of bacteria in a petri dish; it is more like the complex, love–hate relationship we might have with lovers or parents or siblings. It is who we are, unspoken and felt and frustrating and inspiring and vital, and impossible to peer review. You can reach part of it with the analytical mind, but the rest will remain buried in the ancient woodland floor of human evolution and in the depths of our old ape brains, which see in pictures and think in stories.

Civilization has always been a project of control, but you can’t win a war against the wild within yourself. We may have to wait many years, though, before the neogreens discover this for themselves.

![]()

The Conceptual Assassination of Wilderness

DAVID W. KIDNER

THE TIDES...