- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Boston Harbor Islands have been called Boston's "hidden shores." While some are ragged rocks teeming with coastal wildlife, such as oystercatchers and harbor seals, others resemble manicured parks or have the appearance of wooded hills rising gently out of the water. Largely ignored by historians and previously home to prisons, asylums, and sewage treatment plants, this surprisingly diverse ensemble of islands has existed quietly on the urban fringe over the last four centuries. Even their latest incarnation as a national park and recreational hub has emphasized their separation from, rather than their connection to, the city.

In this book, Pavla Šimková reinterprets the Boston Harbor Islands as an urban archipelago, arguing that they have been an integral part of Boston since colonial days, transformed by the city's changing values and catering to its current needs. Drawing on archival sources, historic maps and photographs, and diaries from island residents, this absorbing study attests that the harbor islands' story is central to understanding the ways in which Boston has both shaped and been shaped by its environment over time.

In this book, Pavla Šimková reinterprets the Boston Harbor Islands as an urban archipelago, arguing that they have been an integral part of Boston since colonial days, transformed by the city's changing values and catering to its current needs. Drawing on archival sources, historic maps and photographs, and diaries from island residents, this absorbing study attests that the harbor islands' story is central to understanding the ways in which Boston has both shaped and been shaped by its environment over time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Archipelago by Pavla Šimková in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Massachusetts PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9781625345974, 9781625345967eBook ISBN

97816137687301

The Commons of Boston Harbor

The Harbor Islands and Colonial Boston

Richard Mather was not only a godly man but, to his own mind, also one favored by God’s Providence. After an arduous twelve-week voyage across the North Atlantic, in August 1635 the noted minister and his fellow English colonists aboard the ship James finally glimpsed the coast of New England, the destination of their journey. They made landfall at Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine, and after another brief respite at the Isles of Shoals, a group of rocky islands six miles offshore facing what is today the border between Maine and New Hampshire, continued on the final leg of their voyage to the new colonial town of Boston. The James was about to set sail toward Cape Ann when it got caught in “a most terrible storm of rain and easterly wind” that became known to future generations as the Great Colonial Hurricane. The desperate attempts of the ship’s crew to stay moored and wait out the storm were in vain: the James lost all three of its anchors, and the gale swept the helpless ship toward the rocky coast, its sails ripped to pieces and the passengers trembling for their lives. Yet miraculously, when the storm subsided, the James was still afloat and everyone on board unharmed. Slowly, the tattered ship made its way southwest along the coast and in the evening came to rest in the safe embrace of Boston Harbor. As Richard Mather recalled in his journal, the ship arrived “in a most pleasant harbour, like to which I had never seen, amongst a great many of islands on every side.” After the ordeal of the open sea, there could scarcely be a more paradise-like place on earth to the survivors than these sheltered waters. The James reached Nantasket, just inside the harbor entrance, and that same night, after the evening service, it followed the incoming tide into the deepwater channel that snaked its way among the many islands of the bay and finally arrived in Boston.1

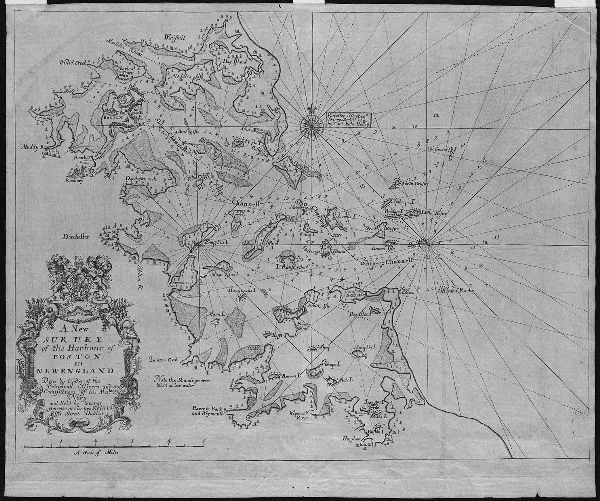

FIGURE 3. A 1708 chart of Boston Harbor from The English Pilot. Special attention has been given both to shipping channels and to shoals, mudflats, and other hazards. This was the coastal environment the Puritans encountered when they arrived in the 1630s.—Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library. This work is licensed for use under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Richard Mather went on to serve as the minister of Dorchester, another township on the shores of Boston Harbor, for the next thirty-three years and became the patriarch of a prominent family of Boston divines that included his son Increase Mather and his grandson Cotton Mather. Despite his exceptional position, his account of his eventful voyage to the New World shared many features with other examples of its genre. The wearisome waiting for westerly wind, the long and strenuous passage across the vast aquatic plain that occasionally transformed into a frightening landscape of welling mountains and valleys of water, and the titillating expectation of a new life in the unknown land beyond the sea were features common to many chronicles of the Atlantic passage.2 As in Mather’s tale of ordeal and deliverance, the coastal islands of New England played a prominent role in other accounts, even those written by colonists who arrived under less dramatic circumstances. Amazed by water-spouting whales, porpoises, and “grampuses as big as an ox” leaping around their ships, but equally wearied after multiple weeks of cramped quarters, inadequate food, and seasickness, the Puritans were relieved to set eyes at last on firm ground that promised solid rock beneath their feet as well as freshwater and grass for their cattle.3 The small, rocky islands lining the New England coast were for the newcomers from the East the first sites of contact with the new continent. Places like the Georges Islands before the coast of Maine, the outlying Monhegan Island twelve nautical miles offshore, the Isles of Shoals opposite the mouth of the Piscataqua River, Thacher Island off Cape Ann, or Bakers Island at the entrance of Salem Harbor have all advanced to local landmarks well known to sailors by the early 1630s. The larger islands were also, naturally, among the first places to be settled by the English, originally as fishing outposts. When the party on the James that included Richard Mather approached Richmond Island off Cape Elizabeth in 1635, they encountered there a colony of some forty fishermen, who “were sore afraid of us, doubting lest we had been French, come to pillage the island.”4 Fishing colonies were common on the Northwest Atlantic coastal islands, but those who came on the Puritan ships were looking for something other than abundant fisheries. For them, the islands were the first emissaries of the land that lay beyond: the first tokens of the fertility of the settlers’ new home. Of more immediate importance, the islands helped create stretches of comparably calm coastal waters and sheltered harbors that provided refuge from the perils of the open ocean; they also signaled the welcome proximity of the continent. Thus, the sight of the Boston Harbor Islands, noted with such delight by Richard Mather, promised both relative safety and a speedy end to the rather unpleasant adventure of the Atlantic crossing.

The “most pleasant harbour” where the James found a safe haven had only recently become the center of the New England colonies. Five years before the James’s dramatic journey, in April 1630, four other English ships set sail from the Isle of Wight towards the New World. They were the Arbella, the Talbot, the Ambrose, and the Jewel, and they carried a company of several hundred settlers that included John Winthrop, the future governor of the colony of Massachusetts Bay. After a nine-week voyage, they made landfall at Salem, the principal port in the earliest days of the New England colonies. The new “planters,” however, did not stay there long, for, as Winthrop’s deputy Thomas Dudley noted, “Salem, where we landed, pleased us not.”5 Probably because of an outbreak of disease that plagued Salem at the time, only a few days after arrival the newcomers sent a small party to survey the coast and identify a place better suited for the new colony. As it happened, such a place lay less than twenty miles to the south: the so-called still bay within the Massachusetts Bay, which in a few years would become known as Boston Harbor.6 The bay was sheltered, with several tributaries that provided access farther inland, and its shores seemed to have good pasturage and freshwater sources. After the initial foray, the rest of the party soon followed and in late June 1630 arrived at the shores of what was shortly to become the town of Boston.7

A World of Islands

When they entered the harbor, the colonists encountered a world of islands. The bay encompassed some thirty of them, varying in shape, size, and height, some overgrown with trees, others little more than sand and gravel shoals. A few of them quickly became familiar landmarks, guiding ships to the new town. When the Arbella and its companions cleared the dangerous rocks and rocky islands at the harbor entrance, which later came to be called the Brewsters and the Graves, they sailed through a deepwater channel past the tip of Deer Island, the northern headland protecting the harbor from the rough seas of the outer bay.8 The southern headland, Point Allerton, would have been obscured by Lovells, Gallops, and Georges Islands, a group of midsize isles huddled closely together at the harbor’s doorstep. After passing on the port side the small, barren island of Nixes Mate, the tip of the large and wooded Long Island, and the northern cliff of Spectacle Island, rising abruptly above the waves, and after successfully avoiding the Lower Middle, a dangerous shoal on the starboard side, the Puritan ships turned northwest and found themselves in the inner bay, lined on both sides with vast expanses of tidal flats and leading up to the destination of their journey, a peninsula at the head of the bay they called Charlestown.

The colonists of John Winthrop’s party were not the first English who settled down in the bay. The islands and peninsulas of the still bay of Massachusetts were home to a handful of English immigrants who had arrived at various points in the 1620s. There was the family of David Thompson on one of the larger islands close to shore that was later named Thompson Island in his honor; there was the rather reclusive Reverend William Blackstone on the hilly Shawmut peninsula, across the water from Charlestown; and there was Samuel Maverick on Noddles Island, a man noted for his hospitality and general agreeableness that to some extent made up for his being “an enemy to the Reformation in hand.”9 Charlestown did not stay the center of the new plantation for long. Plagued by disease and dismayed by lack of drinkable water, most of Winthrop’s colonists soon made good on William Blackstone’s invitation and relocated to the Shawmut peninsula. The settlement they built there they called Boston. Other settlers dispersed around the bay: some went up the Mystic River and settled at Winnisimmet (today’s Chelsea) and Medford. Others sailed, or rather rowed, up the Charles River and founded Watertown, some ten miles upstream from Boston. Others traveled down the shore and settled at spots that became known as Dorchester, Weymouth, and Hingham. Some joined Samuel Maverick on Noddles Island, and yet others stayed in Charlestown. Tellingly, all the early settlers chose islands, peninsulas, or at the very least the seashore as their homes: the islands offered relative safety from whatever dangers lurked on the mainland, and, more important, all these places allowed ready access to the only reliable means of travel, that by water.

The early English colonists in New England had a very ambivalent relationship with the coastal regions. On the one hand, the coastal waters were insecure, ever-shifting spaces where storms raged and shoals, sand spits, and submerged rocks threatened just below the waves. A number of early geographical names bear witness to the dread the region’s topography inspired in the European newcomers: islands ominously called Great Misery or Norman’s Woe, a shoal by the name of Devil’s Back. Other places, such as Thacher Island, Avery’s Ledge, or Collamore’s Ledge, were all named for people who were shipwrecked on them, making them eternal reminders of the grim fate of unfortunate mariners. Early records of the colonies abound with tales of shipwrecks and boating disasters: John Winthrop relates in his journal how in December 1630 one “Richard Garrett, a shoemaker of Boston,” and five others, including his daughter, “went towards Plymouth in a shallop, against the advice of his friends”; they proceeded down the South Shore and were almost at Plymouth when they got caught in a northwest gale that blew them out on the open water. They were able to land on Cape Cod and were assisted by local Natives, but it took days before a rescue party from Plymouth reached them and brought them to safety; by that time, four of them, including Garrett himself, had died of exposure.10

On the other hand, despite being inherently unsafe for the small vessels of the early settlers, the coastal waters offered the only way of communication between the colonies themselves and with the mother country. Pushing inland did not seem a particularly inviting prospect in comparison. Although several European newcomers commented on the open, almost parklike character of the landscape they first encountered in New England, this permeable environment was already changing by the time Boston was founded. The Natives, devastated by European diseases, no longer burned and cleared the forests, which were reverting to an impenetrable tangle of trees and underbrush.11 Devoid of roads and once again overgrown with woods in which wild animals threatened, the mainland did not present a viable way of moving about during the first years of the colony. Water, on the other hand, provided for a comparatively easy way of moving people and goods from one place to another. Besides, compared to the many and largely unknown hazards of the coast, places like Boston Harbor soon became familiar and manageable: the number of dangers posed by navigating Boston Harbor was finite, and they could be learned about and monitored. By 1633 the harbor even had a pilot, John Gallop, who would come aboard incoming ships to guide them safely to the town’s shores.12 Between the threatening woods of the mainland and the shifting bars and violent storms of the coastal waters, Boston Harbor seemed a safe and sheltered space close to home.

The early settlements of the Boston area were quite literally built on water. Not only did most of the shoreline merge seamlessly with mudflats and salt marshes, but all of the towns had water access; some of them had more waterfront than uplands. Water washed the shores of Hingham and Charlestown, it encircled Samuel Maverick’s small palisaded settlement on Noddles Island, and it seeped through the brown-green plains of mudflats stretching for miles from the shore of Dorchester into the bay at low tide. Boston was no different: the Shawmut peninsula, about two miles long and barely one mile across, was enclosed by water from three sides. In the north and west, it was separated from the mainland by the estuary of the Charles River. In the south, a deep cove ran between Boston and the peninsula of Dorchester Neck. In the east, the newly founded town faced the deep water of the harbor. Only in the southeast was the peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow spit of land called the Neck. The Neck was low and marshy and would regularly flood during storms, making the Shawmut, with Boston on it, effectively an island. Even a large part of what passed as firm ground of the peninsula was marshy, and on the mainland beyond the Neck, this waterlogged environment continued in the swampy courses of Muddy River and Stony Brook. Thus, the early town of Boston stood almost completely surrounded by water.

Its location at the water’s edge was one of the reasons the site was chosen for settlement in the first place. Boston’s near-absolute separation from the mainland was seen as an asset by the contemporaries. William Wood, the author of a pamphlet designed to attract settlers to the colony, remarked in 1634 on the early Bostonians’ fortunate situation, as “they are not troubled with three great annoyances, of Woolves, Rattle-snakes, and Musketoes.”13 Given their town’s position, early Bostonians developed what historians Petra van Dam and John T. Cumbler have called an “amphibious culture”: the harbor and its tributaries were for them a source of goods as well as an avenue to move them.14 Fishing and fowling were an early means of sustenance for the colonists, who profited from the productive littoral ecosystem: John Winthrop recorded a “great store of eels and lobsters in the bay” in the summer of 1632, adding that “two or three boys have brought in a bushel of great eels at a time, and sixty great lobsters.”15 Besides keeping the annoyance of rattlesnakes at bay, waterways also acted as roads: boats and pinnaces of all kinds were a common possession among the settlers, who would travel by water from one town to another around the harbor and sometimes venture outside the harbor to visit fellow colonies along the shore. Water connected rather than separated: accessibility...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- introduction

- 1. The Commons of Boston Harbor

- 2. The Ultimate Sink

- 3. The City of Tomorrow

- 4. The Romance of Boston Bay

- 5. A New Spectacle

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index