eBook - ePub

Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge

Ecology, Adaptive Management, and Restoration

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge

Ecology, Adaptive Management, and Restoration

About this book

Cork oak has historically been an important species in the western Mediterranean—ecologically as a canopy or "framework" tree in natural woodlands, and culturally as an economically valuable resource that underpins local economies. Both the natural woodlands and the derived cultural systems are experiencing rapid change, and whether or not they are resilient enough to adapt to that change is an open question.

Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge provides a synthesis of the most up-to-date, scientific, and practical information on the management of cork oak woodlands and the cultural systems that depend on cork oak.

In addition, Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge offers ten site profiles written by local experts that present an in-depth vision of cork oak woodlands across a range of biophysical, historical, and cultural contexts, with sixteen pages of full-color photos that illustrate the tree, agro-silvopastoral systems, products, resident biodiversity, and more.

Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge is an important book for anyone interested in the future of cork oak woodlands, or in the management of cultural landscapes and their associated land-use systems. In a changing world full of risks and surprises, it represents an excellent example of a multidisciplinary and holistic approach to studying, managing, and restoring an ecosystem, and will serve as a guide for other studies of this kind.

Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge provides a synthesis of the most up-to-date, scientific, and practical information on the management of cork oak woodlands and the cultural systems that depend on cork oak.

In addition, Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge offers ten site profiles written by local experts that present an in-depth vision of cork oak woodlands across a range of biophysical, historical, and cultural contexts, with sixteen pages of full-color photos that illustrate the tree, agro-silvopastoral systems, products, resident biodiversity, and more.

Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge is an important book for anyone interested in the future of cork oak woodlands, or in the management of cultural landscapes and their associated land-use systems. In a changing world full of risks and surprises, it represents an excellent example of a multidisciplinary and holistic approach to studying, managing, and restoring an ecosystem, and will serve as a guide for other studies of this kind.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge by James Aronson, João Santos Pereira, Juli G. Pausas, James Aronson,João Santos Pereira,Juli G. Pausas in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781610911306PART I

Cork Oak Trees and Woodlands

In the first part of this book we set the scene as the first step in showing why, when, where, and how to better manage and restore natural and socioecological cork oak systems. These five chapters will give the reader insight into the origins of these systems as we review the main characteristics and origins of the tree and the systems in which it grows and prevails. Oaks live much longer than human beings. Therefore, each human generation inherits a series of landscapes whose origin and history may be lost at any turn in the trajectory of human societies. For example, the rapid urbanization of the late twentieth century changed the public perception of woodlands and the management of forests and agroforestry systems.

In Chapter 1 we address key questions about the tree, such as how it is equipped to survive the hot, dry summers of the Mediterranean climate and what may be the ecological importance of a thick, corky bark in such an environment. The trees we see today result from a long process of reiteration and ongoing adaptation of a genetic blueprint that determines form and function. The environment modulates the final result. For several millennia, people have also had a hand in selecting and modifying the result. It is a three-way process, involving plants, environment, and people, in which survival is a key point. The physiological and morphological characteristics of cork oak discussed in this chapter are essential to our understanding of adaptability and its limits. Note that in Parts II and III we further explore how cork oak copes with adversity (i.e., biotic and abiotic stresses) and review and compare available techniques for restoration and management presented in other parts of the book. Reproduction is left for these more specialized parts of the book (see Chapter 10).

In addition to knowing something about the cork oak tree—form and function—it is important to trace its phylogenetic origins. In Chapter 2, using a panoply of techniques, the authors present the biogeographic structure of the genetic variation of cork oak. We know today that individuals from the western and eastern parts of the Iberian Peninsula geographic range are genetically distinct. Different populations also differ in the likelihood of occurrence of cytoplasmic introgression by the evergreen holm oak, as revealed by the occurrence of ilex-coccifera DNA lineages in cork oak. This has ramifications for managers and restorationists, as will be discussed later in the book. Intriguingly, the role of introgression in the evolutionary history of cork oak is still unknown.

Cork oak woodlands have been remarkable components of Mediterranean landscapes for centuries. This is a result not only of the longevity and size of the trees but also of their usefulness to humans: from cork and firewood to a framework tree for agroforestry and silvopastoral systems. In the absence of human influence, in many cases, these woodlands would tend to be multispecies forests, mixed with other evergreen and deciduous oaks and pines. Especially important are the Iberian montado or dehesa and related land use systems in Italy, France, and North Africa, which are described in detail in Chapter 3 in a broad bioregional and historical fashion that has not been previously attempted to the best of our knowledge.

In Chapter 4 the history of the montado or dehesa is discussed at a finer resolution, based on a case study in a specific region, Evora, in southern Portugal. Clearly, Holocene history and humans have left a layered imprint on the structure and functioning of agroforestry systems, such as the montados or dehesas: How did they arise; in which socioeconomic contexts were they formed; and how did management practices change over time? All these factors condition contemporary ecosystem function and stability.

Finally, in Chapter 5 the unique physical and chemical properties that make cork an outstanding material for industry and as wine bottle stoppers are described, together with the corresponding biological and physical explanations. After characterizing cork as a material, the authors explain how it emerged as a major asset in regional economies in the past. Indeed, most cork oak woodlands would not exist if not for the economic value of cork. Used and traded for centuries, today it is the second most important nontimber forest product in the western Mediterranean. Chapter 16, in Part IV, is devoted to the cork industry and trade today and the prospects for the future.

After reading these chapters, which provide baseline knowledge of the cork oak tree and pertinent woodland systems, the reader will be ready to dig further into the conflicts, constraints, and options available so as to better understand the ancient woodlands that are now in a risky transition, all around the western Mediterranean, moving toward a very uncertain future.

João S. Pereira, Juli G. Pausas, and James Aronson

Chapter 1

The Tree

To understand and appreciate it properly, we should first recognize that cork oak is in many ways a typical Mediterranean tree. It can survive adverse conditions of both human and nonhuman origin. It resists cutting, grazing, prolonged drought, and fire but not extreme cold. On suitable, deep soils and with adequate rainfall, the tree may reach up to 20 meters tall and live for several centuries. However, it has one feature that is extremely rare throughout the plant kingdom: an outer coat of insulation consisting of corky bark of continuous layers of suberized cells (see Chapter 5), up to 20 centimeters thick, that may have evolved as an adaptation to fire (see Color Plates la, 1b). What is more, the tree survives and grows new bark when the original bark on its trunk has been removed.

Like other evergreen Mediterranean oaks, cork oaks survive drought, thanks in part to their extensive and deep root systems. During a drought, the tree may protect crucial organs and tissues from dehydration by closing stomata on leaves, restricting water loss, and the tree’s deep roots may tap water from the deeper soil or subsoil (Pereira et al. 2006). The deep root system of cork oak helps the tree maintain water status and xylem conductance above lethal levels throughout the summer drought period (see Chapter 6). In some cases, under severe drought, the tree may shed its leaves and resprout when the drought is over (in spring). During the early stages of plant life, there is a clear priority for root growth (Maroco et al. 2002). This early investment in roots, rather than in stems and foliage, may contribute to survival in the first years in drought-prone environments because seedling survival cannot be guaranteed before roots reach a soil depth that holds available water in summer. Symbiosis with mycorrhizae that live in or on the roots is also an important aid to cork oak seedlings in resisting drought, as described in Chapter 7.

Once aboveground parts begin to develop, cork oak has a unique leafing phrenology. For an evergreen tree, it has short-lived foliage and a late flushing pattern (Pereira et al. 1987; Escudero et al. 1992). In fact, the average leaf life expectancy is only about 1 year, much shorter than in other evergreen oaks, such as Iberian holm oak (Quercus rotundifolia = Q. ilex subsp. ballota), whose leaves last 1-3 years, or the kermes oak (Q. coccifera), whose leaves can last 5-6 years. Leaf phenology is under strong genetic control, and the beginning of shoot flushing of populations belonging to different provenances but cultivated together can vary by as much as 4 weeks, from late March to late April.

Cork oak leaves themselves are also well designed to cope with an unpredictable climate. They are sclerophyllous, which means they are stiff, thick, and waxy (see Color Plate 1d). This is typical of many trees and shrubs that grow in regions with strong seasonal water deficits, such as the Mediterranean. They are also small, which allows efficient heat dissipation, thus partly avoiding overheating in the hot summer. In cork oak, as in many kinds of trees whose roots tap water from deep in the soil, supplementary cooling is often achieved through transpiration, as stomata open for some time on long summer days. Harmful leaf tissue dehydration is prevented by the highly efficient gradual closure of stomata (see Chapter 6, where other adaptations to drought are discussed in more detail).

Sclerophylly is often considered an adaptive trait of woody plants in seasonally dry climates, but it does not automatically confer greater tolerance to drought, and it may have evolved because it provides protection from many different types of stress (Read and Stokes 2006), such as poor mineral nutrition or attacks by defoliators (Salleo and Nardini 2000). In fact, sclerophylly implies a long leaf development time and fairly high ratio of carbon to nitrogen, both of which traits make the foliage undesirable to herbivores. Thus, most defoliators attacking cork oak feed on the young, tender leaves, before sclerophylly fully develops. This, in turn, conditions the nature of the web of organisms dependent on cork oak leaves.

Biogeography

Cork oak occurs in regions with average annual precipitation above 600 millimeters and average temperature near 15°C (Blanco et al. 1997). In Europe, it is low winter temperatures that appear to set the geographic distribution limits and most cork oak stands are located in areas below 800 meters in altitude. Cork oak leaves are less tolerant to frost (Larcher 2000; Garcia-Mozo et al. 2001) and to drought than those of the more widespread holm oak. In addition, whereas holm oak is indifferent to soil types, cork oak usually grows in acidic soils on granite, schist, or sandy substrates or, more rarely, in limestone-derived soils or in neutral soils overlying dolomitic bedrocks (Chapter 8).

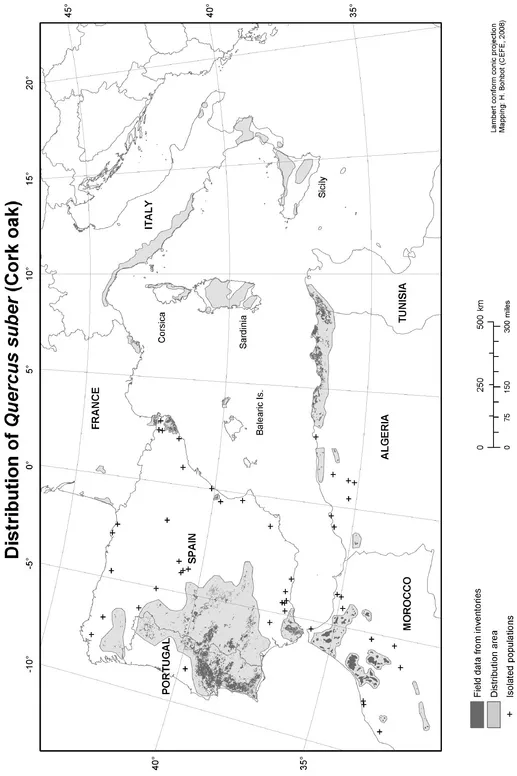

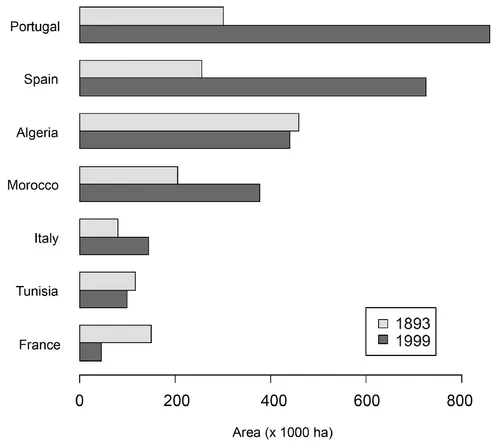

Today cork oak occurs only in the western Mediterranean (Figure 1.1), from Morocco and the Iberian Peninsula to the western rim of the Italian peninsula. It also flourishes on all the large islands between the Iberian and Italian peninsulas, and in scattered parts of southern France and some coastal plains and hilly regions of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Total area today adds up more than 1.5 million hectares in Europe and about 1 million hectares in North Africa (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 shows clearly that cork oak’s current distribution is very patchy and disjunct, which suggests that much of what we see today is relictual. It is also possible that, over past centuries, humans intentionally introduced the tree to some islands and disjunct continental areas where it did not naturally occur. However, in Europe and especially in North Africa, cork oak areas have diminished in size and vitality because of overgrazing, which limits regeneration, and the expansion of plow agriculture in managed woodlands (see Chapter 3), the replacement of cork oak by pine and eucalyptus, imprudent cork stripping, and the extraction of tannins, which kills the tree. Wildfires may also be an important source of cork oak mortality, but mainly after cork extraction, when the lack of protection makes the tree susceptible to fire. In southwestern Spain and Portugal, however, the area of cork oak stands has increased in the last 200 years (Figure 1.2), despite some episodes of decline, such as that in the mid-twentieth century (see Chapter 20).

Phylogenetically, cork oak is considered to be closely related to three Asian species of oak, all of which are deciduous. These are the Turkey oak (Q. cerris) of southwestern Asia, sawtooth oak (Q. acutissima) of eastern Asia, and Chinese cork oak (Q. variabilis) (Manos and Stanford 2001). Moreover, recent genetic studies suggest that the evolutionary origin of cork oak was quite a bit east of its current distribution area (Lumaret et al. 2005; see Chapter 2). Indeed, fossils of the ancestors of cork oak, in the Q. sosnowsky group, have been found in France, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, and Georgia (Bellarosa 2000). However, the origin of cork oak is still under debate (Magri et al. 2007).

In the last century, cork oak was artificially introduced in several countries outside the Mediterranean region, as an ornamental shade tree and botanical oddity or in hopes of generating local cork production. Reasonably good acclimatization has been attained in Bulgaria (Petrov and Genov 2004), New Zealand (Macarthur 1994), southern Australia, Chile, and California. However, none of these places has successfully developed a cork industry, even though the tree grows reasonably well on appropriate soils. At present, despite ongoing tree decline, Portugal remains by far the largest producer of cork and has the largest industry, followed by Morocco, Italy (especially Sardinia), and Spain (see Chapter 5).

FIGURE 1.1. Current distribution of cork oak. (Algeria: Gaussen and Vernet 1958; Barry et al. 1974; Alcaraz 1977; Italy; modified from Bellarosa etr al. 2003b; Motocco: Sbay et al. 2004; Portugal: DGF 2001; Spain: after www.inia.es, 2006; Tunisia: Khaldi 2004, after IFPN-DGF 1995)

FIGURE 1.2. Areas covered by cork oak in different periods and countries. Light bars refer to areas covered in 1893 (Lamey 1893), except for that of Morocco, which refers to 1917 (Boissière 2005); dark bars indicate the area covered in 1999 (Institutodel Corcho, la Madera y el Carbón, Mérida, Spai...

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- ABOUT THE SOCIETY FOR ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION INTERNATIONAL

- SOCIETY FOR ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION INTERNATIONAL

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I - Cork Oak Trees and Woodlands

- PART II - Scientific Bases for Restoration and Management

- PART III - Restoration in Practice

- PART IV - Economic Analysis

- PART V - Challenges for the Future

- GLOSSARY

- REFERENCES

- EDITORS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- SPECIES INDEX

- INDEX

- Island Press | Board of Directors